The Song Dynasty, also known as the Sung dynasty, is one of the most prolific dynasties to ever have ruled the Chinese people, but what exactly is the Song dynasty known for in Chinese history?

what is the Song Dynasty?

The Song Dynasty is a highly significant era in Chinese history, spanning 319 years from 960 to 1279 AD. During this period, China witnessed unparalleled prosperity in its commercial economy, cultural education, and scientific innovation, which had profound and lasting impacts on its history and culture.

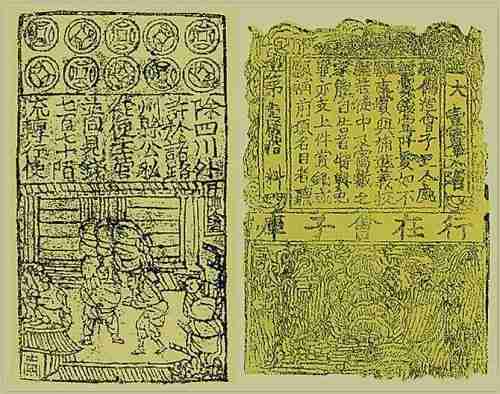

Firstly, the Song Dynasty marked a pinnacle of economic prosperity with a thriving commercial economy. As cities developed and commercial activities flourished, the scale of commodity exchange expanded, and the use of currency became widespread. Particularly during the Southern Song period, commercial activities encompassed various sectors such as tea, silk, porcelain, and more. Moreover, the Song Dynasty saw the emergence of the world’s earliest form of paper currency known as “jiaochao,” further promoting the growth of the commercial economy.

Secondly, cultural and educational achievements thrived during the Song Dynasty. This era gave rise to numerous cultural figures, including literary giants like Su Shi (Su Dongpo) and Xin Qiji, whose works continue to be celebrated and studied to this day. Additionally, the Song Dynasty witnessed the establishment of prominent cultural institutions and venues such as the Imperial Academy (Taixue) and the Imperial College (Guozijian), providing robust support for the advancement of culture and education.

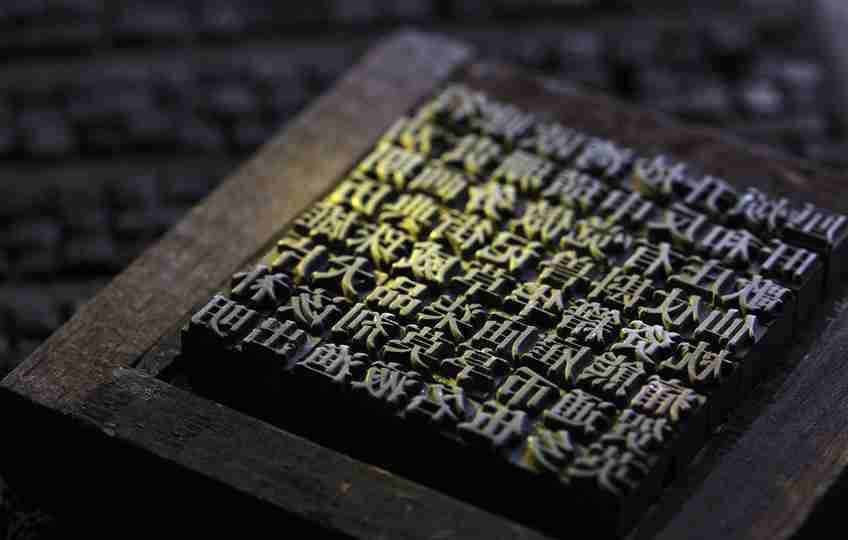

Lastly, the Song Dynasty was a period of remarkable scientific innovation. During this era, three of China’s Four Great Inventions—movable-type printing, gunpowder, and the magnetic compass—were developed. These inventions not only propelled contemporary social progress but also left a profound impact on the development of human civilization. Additionally, the Song Dynasty witnessed significant discoveries and innovations in fields such as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.

In summary, the Song Dynasty was a time of unprecedented achievements in China’s commercial economy, cultural education, and scientific innovation, leaving a lasting legacy on its history and culture.

why was it called the Song Dynasty?

The title of the Song Dynasty, “Song,” originates from “Songzhou,” an area in Henan’s Shangqiu. This is because Emperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty, Zhao Kuangyin, had previously held the position of “Jiedushi” (military governor) in that region. After successfully overthrowing the Later Zhou regime, he chose the character “宋” (Song) as the new dynasty’s title.

how did the song dynasty start?

In the year 960, a group of generals from the Later Zhou Dynasty launched the Chenqiao Uprising, enthroning Zhao Kuangyin, who held the position of military governor of Songzhou, as Emperor. This event led to the establishment of the Song Dynasty. In order to prevent the recurrence of regional separatism and the excessive power of eunuchs that had plagued the late Tang Dynasty, Emperor Zhao Kuangyin adopted a policy of prioritizing civil over military authority. He strengthened centralization and curtailed the military power of warlords. Under the reign of Emperor Taizong, the Song Dynasty unified the entire nation, and during the rule of Emperor Zhenzong, the signing of the Treaty of Chanyuan with the Liao Dynasty marked a transition into a more stable and prosperous era.

Cloaked in Yellow Robes

Zhao Kuangyin served as the Chief Guard Commander of the Imperial Palace for the Later Zhou Dynasty, responsible for leading the palace guards. In the year 960, the founding emperor of Later Zhou passed away, leaving the seven-year-old crown prince to ascend the throne. As conflicts arose in the northern regions, the skilled general Zhao Kuangyin was dispatched to the north for military campaigns. During a rest stop at Chenqiao on the following night, soldiers discussed the nation’s perilous situation and the young and inexperienced emperor. They expressed concerns about their efforts on the battlefield going unnoticed and unrewarded in the future. Fearing that their service to the country would go in vain, they were hesitant to continue fighting. At that moment, a suggestion was raised: why not make Zhao Kuangyin the emperor? The idea garnered unanimous approval.

At that time, Zhao Kuangyin, who had been drinking, was sound asleep. Suddenly awakened, he stumbled out and was immediately surrounded by several soldiers who swiftly draped a yellow robe over him. They then knelt before him, kowtowing and shouting in unison “long live,” proclaiming their support for Zhao Kuangyin as the king. Without delay, they urged him onto a horse and persuaded him to return to the capital city. In the year 960, with minimal effort, Zhao Kuangyin accepted the abdication decree from the young emperor of Later Zhou, Chai Zongxun, and established the Song Dynasty.

Song Dynasty Achievements Timeline.

960 AD: Zhao Kuangyin (later known as Emperor Taizu of Song) initiated the Chenqiao Mutiny, declared himself emperor, and established the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Later Zhou Dynasty ended.

961 AD: Emperor Taizu relinquished military power, centralizing military and political authority.

963 AD: Emperor Taizu conducted a simulated expedition to Jingnan (South Jing) and then to Hunan, leading to the fall of Nanping.

965 AD: Song troops captured Chengdu, leading to the downfall of the Later Shu Dynasty.

971 AD: Song troops arrived in Guangzhou, leading to the fall of the Southern Han Dynasty.

976 AD: Song forces captured Jinling (Nanjing), and Emperor Li Yu surrendered, marking the fall of the Southern Tang Dynasty.

978 AD: The Wuyue Kingdom was incorporated into the Song Dynasty.

979 AD: Emperor Taizong led a campaign against the Northern Han Dynasty in Taiyuan, leading to its fall. The Khitan Liao Dynasty scored a major victory against Song forces at Gaoliang River.

983 AD: The Khitan Liao Dynasty changed its name to the Great Liao Dynasty. The compilation of the “Taiping Yulan” encyclopedia was completed.

984 AD: The Khitan Liao Dynasty constructed the Guanyin Pavilion at Dule Monastery in Jixian, which is the oldest extant wooden-structure tower in China.

986 AD: The Song Dynasty launched an attack against the Khitan Liao Dynasty, and Yang Ye died in battle in Shuozhou.

990 AD: The Khitan Liao Dynasty granted Li Jiqian the title of King of Xia.

993 AD: Wang Xiaobo led a rebellion in Sichuan, but he was killed in battle. Li Shun took over the leadership.

1001 AD: The Kaifeng County Kyuan Tower was built, becoming the tallest brick pagoda that still exists in China.

1004 AD: The Khitan Liao Dynasty launched a major attack on the Song Dynasty, leading to the signing of the Chanyuan Treaty.

1004-1007 AD: Jingdezhen porcelain gained fame during this period.

1005 AD: Yang Yi and others compiled the “Cefu Yuangui” imperial anthology.

1023 AD: Jiaochao (Chinese paper money) was issued in Sichuan, making it one of the earliest known instances of paper currency in the world.

1038 AD: Yuanhao, leader of the Dangxiang people, declared himself emperor, establishing the Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227).

1041-1048 AD: Bi Sheng invented movable type printing.

1043 AD: Song and Western Xia negotiated peace, acknowledging Yuanhao as ruler of Western Xia. Fan Zhongyan implemented reforms but was later dismissed.

1045 AD: Canglang Pavilion was built in Suzhou.

1049 AD: Kaifeng established the Guosi Pagoda, which is the earliest known glazed-brick pagoda in China.

1056 AD: The Fokuang Temple Shakyamuni Pagoda was completed, becoming the tallest extant wooden building in the world.

1057 AD: Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) advocated for a simple and unadorned writing style.

1059 AD: Quanzhou completed the Luoyang Bridge, the first large stone bridge built over the sea.

1061 AD: Dangyang erected the Yuzhu Iron Pagoda, the tallest existing cast iron pagoda in China.

1069 AD: Wang Anshi (1021-1086) initiated reforms known as the “Wang Anshi Reforms.”

1072 AD: Ouyang Xiu passed away. He authored “Zuiweng Tingji” (“Record of the Pavilion of the Drunken Old Man”), co-authored “Xin Tangshu” (“New Book of Tang”), and “Xin Wudai Shi” (“New History of the Five Dynasties”).

1073 AD: Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073) passed away.

1077 AD: Shao Yong passed away.

1084 AD: Sima Guang completed the “Zizhi Tongjian,” the first comprehensive chronicle in China.

1085 AD: Sima Guang took power, abolishing Wang Anshi’s reforms. Cheng Hao passed away, and his teachings, along with those of his brother Cheng Yi, became known as Luoyang School.

1086 AD: Wang Anshi passed away. Sima Guang also passed away.

1088 AD: Shen Kuo wrote “Dream Pool Essays” around this time.

1090 AD: Qin Guan published “Can Shu,” the earliest known treatise on sericulture in China.

1096 AD: The Liao Dynasty constructed the Lama Pagoda of Miao Ying Temple. It was reconstructed in 1279 and is known as the White Pagoda in Beijing.

1100 AD: Li Jie completed “Yingzao Fashi,” the world’s earliest known architectural manual.

12th Century (early): Zhang Zeduan created the “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” painting.

1101 AD: Su Shi (Su Dongpo) passed away.

1102 AD: Song Huizong appointed Cai Jing as a chancellor, launching the “Yuan You Party Purge,” banning “Yuan You Learning,” and erecting the “Yuan You Party Members Stele.”

1105 AD: Huang Tingjian passed away. The Bureau of Sacrificial Rites and the “Huashi Gang” (Flower Stone Regulation) were established.

1106 AD: Li Gonglin passed away.

1107 AD: Cheng Yi passed away. Mi Fu passed away.

1115 AD: Jin Taizu Wanyan Aguda proclaimed himself emperor, establishing the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234).

1119 AD: Song Zhu Yu documented the use of the compass for navigation in “Pingzhou Ketan.” The Jin Dynasty introduced the Jurchen script.

1120 AD: The Qingxi Fangle Uprising occurred in Muzhou (now Nanjing).

1125 AD: Jin forces captured Emperor Tianzuo of Liao in Yingzhou, leading to the fall of the Liao Dynasty. Jin launched a major attack on the Song Dynasty. Song Huizong abdicated to his son Huanyu (Emperor Qinzong).

1127 AD: Jin captured Dongjing (Kaifeng), capturing Emperor Huizong and Emperor Qinzong, leading to the fall of the Northern Song Dynasty. Jin established Zhang Bangchang as the Emperor of Chu, and the capital was established in Jinling. Zhao Gou (Emperor Gaozong) ascended the throne in Nanjing (now Shangqiu), marking the establishment of the Southern Song Dynasty.

1129 AD: Emperor Gaozong fled from Yangzhou to Hangzhou. Jin forces crossed the Yangtze River, pursuing Emperor Gaozong to the sea.

1130 AD: Jin established Liu Yu as the Emperor of Dazi, pardoning Qin Hui and allowing him to return to Song. A revolt led by Zhong Xiang occurred on the shores of Dongting Lake. It was later suppressed, and Yang Mo continued the uprising.

1132 AD: During the defense of De’an, Chen Gui used “fire lances” in combat, representing some of the earliest known firearm usage in the world.

1136 AD: Liu Yu engraved the “Map of China and the Barbarian Lands” and the “Map of Yu’s Travels,” making them the oldest known map woodblock prints in the world.

1138 AD: Jin introduced the Jurchen small script.

1139 AD: The Song-Jin Peace Treaty was signed. Jin ceded territories in Henan and Shaanxi to Song.

1140 AD: Jin violated the peace treaty, recapturing Henan and Shaanxi. The Battle of Yancheng resulted in a significant victory for the Yuejia Army against the Jin forces. Emperor Gaozong listened to Qin Hui and forced Yue Fei to withdraw.

1141 AD: Emperor Gaozong dismissed Yue Fei, Zhang Jun, and Han Shizhong from military authority. Another Song-Jin Peace Treaty was signed.

1142 AD: Song and Jin divided their territories. Emperor Gaozong, under the name “Chen Gong,” made a false oath. Jin recognized the Prince Kang as the Emperor of Song. Qin Hui falsely accused and had Yue Fei executed.

1151 AD: Jin relocated its capital to Yanjing (Beijing). Song completed the Anping Bridge (Wuli Bridge) in Quanzhou, making it the longest stone bridge with a movable span that still exists in China.

1155 AD: Yang Jia created the “Map of the Six Classics,” which is the earliest known woodblock-printed map. Li Qingzhao likely passed away around this year.

1160 AD: The Song Dynasty began issuing “Huihui Zhi,” a type of banknote, in the regions of Zhejiang and Jiangsu.

1161 AD: Jin launched a large-scale attack on Song. Song general Li Bao defeated the Jin navy using fire arrow rockets at Chenjiadao in Jiaoxi. Song general Yu Yunwen defeated the Jin army at Caishi, utilizing “thunderclap bombs.”

1164 AD: Another Song-Jin Peace Treaty was signed. Song acknowledged Jin’s ruler as “nephew emperor,” ceded Hai, Si, Tang, Deng, Shang, and Qin territories, and paid annual tributes of gold, silver, and silk.

1169 AD: The construction of Guangji Bridge, the world’s first large stone bridge with a combined swing and lift span, began in present-day Chao’an, Guangdong.

1192 AD: Jin completed the Lugou Bridge, the oldest existing segmental arch stone bridge in China.

1195 AD: Zhao Ru Yu and other prime ministers were demoted. Han Tuozhou wielded power and initiated the Kaisui Yuan Party Purge.

1199 AD: Yang Zhongfu created the “Tongtian Calendar,” determining the length of a year as 365.2425 days, which is equivalent to the average length of the contemporary Gregorian calendar year.

1200 AD: Zhu Xi passed away. His sayings were later compiled into “Zhu Zi Yu Lei.”

1206 AD: Temüjin established the Mongol Empire and assumed the title of Genghis Khan (1162-1227).

1207 AD: Xin Qiji passed away.

1208 AD: The Song and Jin Dynasties renegotiated the peace treaty. They were recognized as elder and younger states, and the annual tribute was increased. Han Tuozhou led the ransom of Huainan territory.

1210 AD: Lu You passed away.

1211 AD: Genghis Khan initiated an attack on the Jin Dynasty, marking the beginning of the Mongol-Jin War.

1214 AD: Jin relocated its capital to Nanjing (Kaifeng), which became known as the “Southern Migration of Emperor Xuanzong.”

1215 AD: Mongol forces reached Beijing and Zhongdu (present-day Beijing) in the Jin Dynasty.

1217 AD: Jin launched an attack on the Song Dynasty, leading to continuous conflicts between Song and Jin.

1227 AD: The Mongols extinguished the Western Xia Dynasty. Genghis Khan passed away.

1227-1279 AD: Huang Daopo promoted the production of cotton textiles.

1234 AD: The Mongols and the Song Dynasty captured Caizhou, leading to the fall of the Jin Dynasty.

1247 AD: Qin Jiushao wrote “Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections.”

13th Century (50s) to early 14th Century: Yuan zaju (variety plays) reached their peak in creative production. Renowned playwrights included Guan Hanqing, Bai Pu, Ma Zhiyuan, Wang Shifu, and Zheng Guangzu. Notable works included “The Injustice to Dou E,” “The Wall-Picking at Horse’s Head,” “Autumn in the Han Palace,” and “The Story of the Western Wing.”

1254 AD: Kublai Khan conquered the city of Dali in Yunnan, leading to the fall of the Dali Kingdom.

1257 AD: Yuan Haowen passed away.

1259 AD: Mongke Khan besieged the city of Diaoyu in Hezhou, Sichuan. In the same year, Song Shouchun Prefecture produced a “fire lance” using gunpowder, one of the earliest known gunpowder-fueled firearm prototypes.

1260 AD: Kublai Khan assumed the position of Great Khan. The War of the Princes began.

1267 AD: Construction of Khanbaliq (Dadu), present-day Beijing, began and was completed in 8 years.

1268 AD: Kublai Khan launched a siege on Xiangyang and Fancheng. The Song army defended staunchly.

1271 AD: Kublai Khan proclaimed the Yuan Dynasty and adopted the reign title of “Great Yuan.”

1272 AD: The capital Khanbaliq was renamed “Great Capital” (Dadu).

1273 AD: Yuan forces breached Fancheng, and Xiangyang surrendered.

1274 AD: Kublai Khan ordered Bayan to lead troops to represent the Song Dynasty.

1275 AD: Yuan forces advanced towards Lin’an (Hangzhou), prompting Wen Tianxiang and others to rise in rebellion. Marco Polo arrived in China and later wrote “The Travels of Marco Polo.”

1276 AD: Yuan forces captured Lin’an, capturing the Song emperor, empress dowager, and others, who were later sent north.

1278 AD: The young Song emperor took refuge in Haizhao Mountain in Xin’an. Wen Tianxiang was defeated and captured.

1279 AD: Yuan forces breached Haizhao Mountain. Lu Xiufu carried the young emperor into the sea, and the Song Dynasty fell.

song dynasty major accomplishments

The major achievements of the Song Dynasty include:

Jiaochao (交子): The world’s earliest known paper money, which played a significant role in promoting the development of the Song Dynasty’s commercial economy.

Song Ci (宋词): A distinctive style of poetry that became one of the iconic literary genres of the Song Dynasty. Over 20,000 Song Ci poems have been preserved to this day.

Song Porcelain (宋瓷): Song Dynasty porcelain is renowned for its exquisite craftsmanship and distinct characteristics. With the development of maritime trade, these porcelain wares were exported abroad and became renowned Chinese ancient artworks both domestically and internationally.

Moveable Type Printing (活字印刷术): Moveable type printing technology greatly accelerated the speed of ancient printing.

Compass (指南针): The compass found widespread applications in geodesy, travel, military, and navigation.

Gunpowder (火药): Gunpowder empowered Song Dynasty warriors to better defend against invasions from various directions.

Medicine (医学): The Song Dynasty witnessed the creation of the world’s first forensic treatise “Xiyuan Lu” and the world’s first pediatric monograph “Luzi Jing,” both significant contributions to medical history.

why was the song dynasty a golden age?

The Song Dynasty is often referred to as the “Golden Age” for several reasons:

Firstly, the economic development during the Song Dynasty contributed to cultural prosperity. As the economy shifted towards a market-oriented structure, cultural and entertainment activities became more accessible to the general populace, leading to diverse cultural expressions. The widespread popularity of ci poetry, the emergence and development of vernacular illustrated novels, and other cultural endeavors injected new vitality into the cultural landscape of the Song Dynasty.

Secondly, the growth of the southern economy fostered progress and prosperity in southern culture. Prior to the Song Dynasty, the cultural development in the southern regions lagged behind, lacking in humanistic richness. With the economic center moving southward, bolstering material resources, the cultural lag in the south began to improve, leading to the advancement of southern culture, which in turn elevated the overall cultural level of the nation.

Furthermore, the flourishing market economy of the Song Dynasty gave rise to larger commercial cities. These cities became hubs of cultural exchange, where urban culture’s accessibility facilitated the development of various performing arts such as storytelling, singing, and dramatic performances. In this environment, the generous treatment of literati officials, coupled with the prosperity of scholarly culture, contributed to the growth of cultural activities.

From a perspective of historical evolution, the transition from the Tang to the Song Dynasty marked a significant transformation in Chinese history. The rising status of local aristocrats and landowners helped to break the monopoly of aristocratic families on culture, creating fertile ground for cultural development. Simultaneously, the development of a monetary economy and improved economic status provided ample space and freedom for private economic growth, facilitating shifts in societal psychology and values. Individual freedom consciousness among the people strengthened significantly, directly driving the cultural development of the Song Dynasty.

Moreover, the Song Dynasty implemented a lenient cultural policy. Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism were allowed to coexist harmoniously, and various schools of thought were allowed to flourish. The Song Dynasty displayed a tolerant attitude towards different ideological, academic, and literary art movements, fostering mutual exchange and promotion among various academic disciplines. The cultural tolerance policy also extended to poets, as though there were instances of poets being imprisoned, outright executions were relatively rare. This provided a conducive environment for the development of cultural figures.

how did the song dynasty unify china?

Occupation of Jinghu:

The regions of Jingnan and Hunan were strategically located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. They bordered each other to the north and were adjacent to various neighboring states, including Nan Tang to the east, Hou Shu to the west, and Nan Han to the south. The occupation of Jinghu (Jingnan and Hunan) would effectively fragment the southern states, creating favorable conditions for further conquests. In pursuit of this objective, the Song court decided to launch a military campaign into Jinghu.

In the third year of Jianlong (962), in October, Zhou Xingfeng, the Military Commissioner of Wuping, passed away, and the eleven-year-old Zhou Baoquan succeeded him. Taking advantage of the situation, Zhang Wenbiao, the Inspector of Hengzhou, staged a rebellion and captured Tanzhou (capital of Hunan, located in Changsha), while also threatening Langzhou (capital of Wuling, located in Changde). Zhou Baoquan sought assistance from Northern Song to counter Zhang Wenbiao’s threat. Emperor Zhao Kuangyin devised a strategy similar to the “False Surrender of Guo” to simultaneously attack Jinghu and Jingnan, achieving dual victories with one action. In the first year of Qiande (963), in January, he appointed the Military Commissioner of Shannan East Circuit, Murong Yanzhao, as the Commander of the Advance Army in charge of the Southern Expedition to Hunan. He assigned Li Chuyun, the Deputy Privy Councillor, as the Commander and directed him to lead an army of ten provinces to assist in the suppression of Zhang Wenbiao. The campaign was conducted under the guise of lending aid to Hunan while traveling through Jingnan.

In the second month of 963, Song forces simultaneously advanced by land and water, breaking through the Three Rivers Estuary (between Nanyueyang and Beiyueyang), seizing 700 warships, and capturing Yuezhou (capital of Baoling, located in Yueyang, Hunan). On the tenth day of the third month, Langzhou was captured, and Zhou Baoquan was taken captive, resulting in the pacification of Hunan.

Conquest of Later Shu:

Following the pacification of Jingchi, the Song court turned its attention towards Shu (Later Shu). Upon hearing the news, Meng Chang, the ruler of Later Shu, planned to defend his territory by capitalizing on its strategic location in Sichuan and Shaanxi. He fortified his defenses and sought an alliance with North Han to jointly oppose the Northern Song. Emperor Zhao Kuangyin managed to capture the defector Zhao Yantao, a general of Later Shu, gaining valuable information about the enemy’s military disposition. With this intelligence, he decided to launch a military campaign.

In the second year of Qiande (964), in November, he divided his forces into two routes. In the northern route, Wang Quanbin, the Military Commissioner of Zhongwu, was appointed as the Commander of the Western Sichuan Expeditionary Army’s Vanguard. He was assisted by Cui Yanzhi, the Deputy Commander, and led a force of 30,000 cavalry and infantry southward along the Jialing River. In the eastern route, Liu Tingrang, the Deputy Commander of the Imperial Guard’s Mounted Forces, led a force of 20,000 cavalry and infantry to advance westward through Guizhou (capital of Hubei Zigui). The two armies planned to converge and launch a joint attack on Chengdu, the capital of Later Shu.

In the second month of 964, during the lunar new year, the Song forces achieved a major victory. The army led by Shi Yande, the Deputy Commander of the Mounted Forces, captured the city of Xian (located in Hubei), defeating the Later Shu army, capturing commanders such as Han Baozheng and Li Jin, and causing significant losses to the enemy. Encouraged by this success, the Song forces pressed forward, capturing numerous cities and tightening the grip around Chengdu. Facing imminent danger, Meng Chang appointed his heir, Meng Xuanzhe, with no military experience, as the commander-in-chief, entrusting him with the defense of Jianmen Pass, a critical stronghold for Later Shu. Meanwhile, Song forces continued their advance, besieging Jianmen Pass from both the north and south. The strategic combination of the northern and southern forces resulted in the fall of Jianmen Pass and the subsequent defeat of the Later Shu army.

As the situation grew dire, Meng Chang appointed Wang Zhaoyuan as the commander of the Northern Expeditionary Army, tasked with defending key passes such as Lizhou (located in Mian Valley, Sichuan), and Jianmen Pass. However, the joint efforts of Song forces led by Wang Quanbin and Shi Yande managed to capture Jianmen Pass, and later Wang Zhaoyuan, resulting in the complete collapse of Later Shu.

Conquest of Southern Han:

Following the conquest of Jinghu and Later Shu, Southern Tang and Wuyue submitted to the Song Dynasty. However, Southern Han, ruled by Liu Yan, resisted joining the Song. In the second year of Kaibao (969), in June, Emperor Taizu appointed Wang Ming as the Supply Commissioner for Jinghu, preparing for war supplies.

In the third year of Kaibao (970), in September, the Defensive Commissioner of Tanzhou, Pan Mei, was appointed as the Commander of the Hezhou Expeditionary Army. He led troops from ten prefectures to break through and capture Hezhou in Guangxi. Pan Mei claimed he would take the route along the He River to attack Xingwangfu (Guangzhou) in the east, with the intention to lure and defeat the main forces of Southern Han. When Liu Yan sent the general Wu Yanrou to lead a naval force up the Yu and He Rivers to reinforce Hezhou, the Song army ambushed and defeated them, killing Wu Yanrou and capturing Hezhou.

In December, the Song forces advanced to Shaohzhou in Guangdong. Li Chengwo, the Commander-in-Chief of Southern Han, led an army of one hundred thousand to Lianhua Peak (southeast of Shaoguan), where they set up an elephant formation to face the Song forces. However, the Song forces broke through the formation with their powerful bows and crossbows, capturing Shaohzhou.

In the fourth year of Kaibao (971), in January, the Song forces captured Yingzhou and Xiongzhou in Guangdong. In February, they advanced to Majing (north of Guangzhou), using fire to defeat the Southern Han commander Guo Chongyue and his sixty-thousand troops. They then conquered Xingwangfu and Liu Yan surrendered, leading to the fall of Southern Han.

Conquest of Southern Tang:

After the conquest of Southern Han, the ruler of Southern Tang, Li Yu, submitted and sought to preserve his realm by complying with the Song. However, Emperor Taizong aimed to unify the southern regions. After two years of preparation, in September of the seventh year of Kaibao (974), he appointed Cao Bin as the Commander of the Southwest Expeditionary Army. Along with the Deputy Commander, Pan Mei, they led a force of one hundred thousand to march from Jingnan. The Wu Yue army was also called upon to move from Hangzhou and support the campaign. Meanwhile, Wang Ming was tasked with diverting the forces of Southern Tang in Hukou to ensure the safety of the main forces advancing eastward.

In October, Cao Bin led his forces downstream along the Yangtze River, capturing Chizhou in Anhui and Caishi in northern Dangtu, Anhui. In mid-November, they constructed a floating bridge at Caishi to facilitate the crossing of the river and continued their eastward advance.

In the eighth year of Kaibao (975), in January, the Song forces captured Lishui in Jiangsu, and then engaged in a decisive battle against the Southern Tang army at the Qinhuai River in Nanjing. They defeated the Southern Tang forces, advanced to Jiangning, and, with the cooperation of the Wu Yue and Wang Ming forces, annihilated a relief army of one hundred thousand commanded by Southern Tang’s general Zhuyun Hou Zhu Lingyun. On November 27th, they captured Jiangning, and Li Yu surrendered, marking the end of Southern Tang.

Conquest of Northern Han:

With the unification of Jiangnan, the Song Dynasty’s strength grew significantly. Emperor Taizong, Zhao Guangyi, was determined to continue the mission of his predecessor, Emperor Taizu, to conquer Northern Han. Aware that Northern Han had aligned with the Liao Dynasty, Emperor Taizu had attempted three campaigns against Northern Han but was defeated by Liao’s reinforcements each time. He devised a strategy to besiege the city while intercepting Liao reinforcements, then capture Taiyuan after pushing back the Liao forces. In the fourth year of Taipingxingguo (979), in January, he personally led a large army to initiate the campaign.

In the fifteenth day, Emperor Taizong advanced directly from Zhenzhou to Taiyuan. Northern Han urgently requested aid from Liao. Liao dispatched Yelü Sha, the Prime Minister of the Southern Capital, as the Commander-in-Chief, and Yelü Dilie, the King of Ji, as the Supervising General, to lead troops from the east. They also assigned Yelü Shanbu, the Military Commissioner of Datong, to lead troops from the north. In March, Yelü Dilie was ambushed at Shilingguan and suffered a major defeat, losing his life. Soon after, the northern Liao forces were also repelled. In mid-April, the Song forces cleared the surrounding areas and gathered their strength to launch a massive attack on Taiyuan. Liu Ji, the ruler of Northern Han, was forced to surrender on May 6th, and Northern Han was conquered.

Central Plains Unification:

The war to unify the Central Plains lasted for eighteen years. The Northern Song Dynasty successively eliminated the three southern states of Nanping (Jingnan), Later Shu, and Southern Han. In the eighth year of Kaibao (975), they also defeated the powerful Southern Tang. Subsequently, local powers such as Wuyue, Fujian, Zhangquan, and others voluntarily submitted to the Song Dynasty. The conquest of Northern Han effectively unified the entire country. This marked the end of the era of fragmentation and separatism since the An Shi Rebellion of the Tang Dynasty and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, achieving the reunification of the major regions of North and South China.

when was the song dynasty unify china

In the year 979 AD, under the rule of Emperor Taizong (Zhao Guangyi), the Song Dynasty successfully eradicated ten independent regimes and unified China. This marked the end of an era of fragmentation and established a relatively stable and centralized rule over a significant portion of Chinese territory. It’s worth noting that the Song Dynasty only managed to unify certain regions of China. Notably, the Sixteen Prefectures in the northern region (represented by today’s Beijing) were not within the boundaries of the Song Dynasty, resulting in the loss of the Great Wall as a military barrier against the northern Liao Dynasty. Additionally, regions in the southwest such as Yunnan and Guizhou were not under Song rule; instead, the independent state of Dali existed. In the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, smaller states emerged after the decline of the Tibetan Empire. The Hexi Corridor in the northwest was controlled by the Western Xia Kingdom. Consequently, the Song Dynasty did not achieve complete and comprehensive unification of China.

What Is The Song Dynasty Best Known For?

The Song of Sung dynasty is known to have ruled China from the year 960 to 1279CE, and they boast a reign that was split into two main periods – The Northern Song of 960-1125 CE and the Southern Song 1125-1279CE.

The Northern Song dynasty is the dynasty that ruled the largely united China from their capital in Kaifeng. However, things changed when the northern part of this state was invaded by the state of Jin during the first quarter of the 12th Century CE. As a result, the northern Song had their capital moved to the South in Hangzhou.

And even despite the relative level of modernization in China at the time, the Song dynasty made a great deal of its economic wealth in the course of the period that the Song dynasty ruled. At the time, the Song court was plagued with various political factions as well as conservatism which couldn’t hold to the challenge from the Mongol invasion. The Song dynasty would eventually collapse and be replaced by the Yuan Dynasty in 1279CE.

But what exactly is the Song dynasty known for?

As a result of the chaos and the political void that resulted in the Tang Dynasty’s collapse and the subsequent breakup of China into the 5 known dynasties and the 10 kingdoms, there would be one warlord that would rise to the challenge and create a semblance of a unified China. This resulted in the formation of the Song Dynasty that was led by the Later Zhou, general Zhao Kuangyin – who was subsequently endorsed as the emperor of the Song dynasty in 960CE. Song Dynasty’s general had the title Taizu or the Grand Progenitor, who made sure that there was no rival general that would be more powerful than him.

He also came up with a system of rotation for his army leaders, sweeping away all the opposition while also ensuring that the civil service would, from then henceforth, enjoy a higher status than the army acting like the supervisory body.

Emperor Taizu of Song was then succeeded by Emperor Taizong, his younger brother. Emperor Taizong reigned the dynasty from 976 – 997CE. This level of stability offered the longest reign for the first 2 Song emperors, making it one of the most successful dynasties throughout China’s history.

The Song period is well known for the widespread printing of the Confucian classics. One of the things that the Song Dynasty is well known for is the organized trade guilds, paper currency came into use to a large extent, and cities with over 1,000,000 people started to flourish.

Learning and literature were also brought to the Chinese people, and this led to the flourishing state schools and private academies that were always growing in numbers, even as competition for the civil service examinations increased. Things like Neo-Confucianism were systemized into coherent doctrines.

The other notable thing about the Song dynasty is the fact that this Chinese dynasty was notable for the many artistic achievements that were made then.

The Bianjing-based dynasty Bei Song also kicked off the renewal of literature, the arts, and Buddhism. The greatest painters and poets of Chinese history were also popular during the Song Dynasty.

Notably, the last of the Northern Song emperors was one of the most notable artists/ art collectors of the time. And to show his love of art, the capital city of the Song dynasty, Kaifeng, was filled with the greatest beauty, temples, abounding in the palaces, and even the tall pagodas. The Song architects also curved an eave line of the roof upwards at the corners.

And after the Tang dynasty, the Song dynasty was regarded as the golden age thanks to the prosperous economy and the very radiant culture.

The other things that the Song dynasty is known for are the enhanced agriculture setup and the improvement of the productive technologies around agriculture. The technologies improved the overall output of food.

The handicraft industry was also enhanced, with the division of labor as one of the big things that resulted in advanced societies. All these resulted in advanced economic levels that made the dynasty more powerful.

List of Emperors of Song Dynasty

Northern Song between 960 and 1127 had the following emperors

- Emperor Song Taizu (Zhao Kuangyin) – 960 – 976

- Emperor Song Taizong (Zhao Guangyi) – 976 – 997

- Emperor Song Zhenzong (Zhao Heng) – 997 – 1022

- Emperor Song Renzong (Zhao Zhen) – 1022 – 1063

- Emperor Song Yingzong (Zhao Shu) – 1063 – 1067

- Emperor Song Shenzong (Zhao Xu1) – 1067 – 1085

- Emperor Song Zhezong (Zhao Xu3) – 1085 – 1100

- Emperor Song Huizong (Zhao Ji) – 1100 – 1125

- Emperor Song Qinzong (Zhao Huan) – 1126 -1127

Southern Song Emperors (1127-1279)

- Emperor Song Gaozong (Zhao Gou) – 1127 – 1162

- Emperor Song Xiaozong (Zhao Shen) – 1162 – 1189

- Emperor Song Guangzong (Zhao Dun) – 1189 – 1194

- Emperor Song Ningzong (Zhao Kuo) – 1194 – 1224

- Emperor Song Lizong (Zhao Yun) – 1224 – 1264

- Emperor Song Duzong (Zhao Qi) – 1264 – 1274

- Emperor Song Gongdi (Zhao Xi’an) – 1275 – 1276

- Emperor Song Duanzong (Zhao Shi) – 1276 – 1278

- Emperor Song Weiwang (Zhao Bing) – 1278 – 1279

Song Dynasty Achievements And Inventions

The biggest inventions and achievements by the Song Dynasty include some of the greatest inventions and scientific innovations. But unlike their influences over religion, culture, and philosophy, most of the scientific advances by the Song dynasty were lost and even forgotten about by the later dynasties.

Notably, the Song and the Han eras stand out as the two popular Chinese dynasties that had the most rapid technical and scientific advancements. The Song dynasty had scientists that boasted a vast wealth of knowledge from (and of) different geographical regions and the world. Their range of knowledge was wide and expansive, ranging from astronomy and magnetism/ compass to architecture, mechanical engineering, and chemistry, among other subjects.

Solid political foundation

Although the political foundation established then didn’t last for a very time, and the fact that the Song dynasty came in after the Tang Dynasty’s political collapse, the Song Dynasty, under the leadership of Emperor Taizong, would rise to the challenge, bringing the states together into what became some semblance of a more unified China. The Song Dynasty is, therefore, the dynasty that created a sense of political stability in China. Emperor Taizong, also known as the Grand Ancestor, reigned between 976-997, and the stability of his leadership led to the reigns of the leading Song emperors for the Song Dynasty.

Art and science scenes were revolutionized.

The other things that the Song Dynasty is notable for include:

Growing rice and drinking tea became the Chinese thing only after the Song Dynasty came to be – the Chinese were primarily wheat and millet-eating individuals who drunk wine, and they actually were more Western than they were Eastern before the Song Dynasty took the reins.

The Song dynasty also encouraged education, and they were known for their cultural brilliance, which is seen in the landscape paintings from the time, unique architectural pieces, and even the most brilliant pieces and designs for pottery, all pieces boasting a great level of class and simplicity.

Literature was booming during the Song dynasty’s rule as well, and the Lie Jie famous treatise on architecture is proof of the booming literature from the time. The fact that there are numerous encyclopedias from the period is also proof of the evolved level of the written word. Some of the other famous works from the time include the Comprehensive Mirror for Aid to Government (Zizhi tongjian), written by Sima Guang and published in the 1084CE – this publication covered Chinese history from with everything that happened between 403BCE – 959CE. There was also a large number of poetry published.

And as mentioned above, the world of visual arts was evolved as well, with an ever-rising demand for the flourishing arts by the middle class. Theatre and fine porcelain all flourished during the reign of the Song Dynasty.

- Literature and Arts

The other reason for the economic boom for the Song dynasty is the fact that farming was thriving. The farming methods employed were much more efficient, and the developed technologies would result in the production of more foods than needed, which meant that the surplus would be up for sale. The city’s populations increased; as a result, there were thriving markets, with the rural farmers growing more crops with the highest demand like oranges, cotton, sugar, tea, and silk. The seas and canals made transportation of these goods possible, even as companies grew much bigger and more sophisticated in terms of ownership and management. There was an increasing number of stock companies, wholesalers, guilds, and partnerships, all resulting in a booming Chinese economy, as the country started to take on what can now be compared to an industrial model by today’s standards.

- Elegant Architecture

With education and engineering encouraged, the Song Dynasty also saw the development and design of some of the best architectural pieces. The most notable of these was the Duogong flexible joints, as well as their wooden architecture, which are now considered the Song dynasty’s biggest inventions. These features involved the erection of massive wooden structures, specifically in the parts of China that were very prone to earthquakes. These architectural techniques would subsequently be adopted across East Asia.

Song Dynasty Economy And Trade

In addition to the prospering art and education scenes, the other thing that was at its best during the Song Dynasty’s time was the economy. With Kaifeng already the capital for the dynasty and even earlier dynasties, it was the perfect metropolis under Song, and not just for China but the rest of the world at the time. This city had a population of over 1million, and it benefited from the high level of industrialization along with the constant supply for the mines that produced iron and coal. Kaifeng was, in other words, the major trade center. It was also quite famous for its paper, printing, textile, as well as porcelain industries. All these and the overall success of the dynasty’s economy were made possible by the Silk Road that encouraged the successful transportation of goods across the Indian Ocean. The exported goods included silk, tea, copper, and rice. Some of the things imported include camels, sheep, ivory, cotton cloth, spices, and gems.

Why Was The Song Dynasty Important?

The reign of the Song Dynasty is considered one of the most important times in Chinese history, and the main reason for this is the fact that under this dynasty’s rule, there were numerous advancements and inventions that were made, with some of the biggest inventions of things like the gunpowder, the magnetic compass, and more reliable architectural works made at the time. The Song Dynasty is also the first of the Chinese dynasties to have a naval standing throughout world history, building ships that were more than 300ft long, with onboard catapults and watertight compartments which could easily toss huge rocks on China’s enemies. The invention of the big movable pieces of printing equipment is also what allowed for the mass printing of books and other documents. Arts and culture flourished, tea and rice became important things to the Chinese, and the dynasty also conquered the Mongols.

In terms of philosophy and religion, Neo-Confucianism was adopted during the Song Dynasty’s time.

So, with these as just some of the few things that the Song Dynasty was known for, it makes sense that it was the most important of the Chinese dynasties.

When Did The Song Dynasty Start And End?

The Song Dynasty, also known as the Song Empire, was in existence between the years 960 and 1279. It is considered to be China’s biggest and most powerful empire that brought the biggest scientific, economic, and military developments to the country.

Why Did The Song Dynasty End?

There are different things that contributed to the end/ collapse of the Song Dynasty, but the main reasons include:

Political corruption, as well as invasions from external tribes, as well as the civilian uprising that ended up weakening the Northern Song Dynasty.

There was also a weakening in the overall strength of the military that ran things from the Northern Song, and the country was unable to withstand the new invasions from the Jin dynasty. So, in 1127, the Jin army was able to capture the Northern Song capital of Kaifeng, subsequently bringing to an end the reign of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Although the Southern Song and the Mongolian Kingdom eventually overthrew the Jin Dynasty, they would find themselves in turmoil, and they were later conquered in 1279 after the Mongolian king died and their new king, Kublai Khan, ended their relationship with the Song Dynasty, resulting in the subsequent collapse of the Song Dynasty.

Why Is The Song Dynasty Divided Into Two Periods The Northern Song And The Southern Song

The division of the dynasty into two eras, the Northern and the Southern Song Empires, is primarily because these empires ruled at different times and with different coalitions and leaders. The Song Dynasty started as the Northern Song Empire, which was defeated in 1127, but made into the Southern Song Empire after the coalition with the Mongolians, from 1127 to 1279.

In other words, the Song Dynasty ruled in two distinct eras/ time periods, hence the differences in the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

Why Did the Song Dynasty End?

The reasons for the fall of the Northern Song and Southern Song Dynasties are numerous.

Northern Song Dynasty:

The collapse of the Northern Song Dynasty can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the lack of military preparedness from its inception weakened its ability to defend against external invasions. The political ideals and policy arrangements of that time led to the weakening of the military, resulting in a deficiency of capable generals and strong soldiers. This made the Northern Song often unable to effectively resist foreign invasions, leading to a reliance on peace treaties or financial concessions, ultimately contributing to its downfall.

Secondly, rampant corruption within the imperial court of the Northern Song Dynasty played a significant role in its demise. The era of Emperor Huizong was marked by corruption among the bureaucratic and aristocratic elites, who indulged in luxury and excess. This led to public anger and unrest, leaving the country vulnerable from within. The political culture of corruption not only eroded the Northern Song’s national strength but also rendered it more fragile in the face of external aggression.

Additionally, the political culture of flip-flopping policies also had a detrimental impact on the Northern Song’s stability. The incessant power struggle between the New and Old Party factions not only consumed a significant amount of political resources but also created chaos in national defense and personnel matters. This internal strife seriously weakened the Northern Song’s ability to resist external threats and laid the groundwork for its downfall.

Southern Song Dynasty:

The fall of the Southern Song Dynasty was influenced by both internal governance issues and external pressures. Firstly, the decision-makers within the Southern Song Dynasty lacked competence, missing the opportunity to destroy the Great Wall. This disregard for military defense left the Southern Song isolated and vulnerable when facing the onslaught of Yuan Dynasty forces.

Secondly, the loss of the strategically important region of Xiangyang significantly weakened the Southern Song’s military position. The fall of Xiangyang to the Yuan forces deprived the Southern Song of a crucial defensive outpost. This loss left the Southern Song government unable to effectively resist the Yuan Dynasty’s military campaigns, leading to its collapse.

Simultaneously, the Yuan Dynasty’s military campaigns southward played a pivotal role in the fall of the Southern Song. With the loss of Xiangyang, the Southern Song’s ability to resist militarily gradually eroded. The advancing Yuan forces pursued their advantage, pushing further southward and putting the Southern Song on the defensive. This external pressure hastened the collapse of the Southern Song Dynasty.

Song Dynasty system of government

The political system of the Song Dynasty largely followed the model of the Tang Dynasty, employing a decentralized system of dividing administrative powers. The position of the Chancellor was no longer held by the heads of the three ministries as in the Tang Dynasty. Instead, it was renamed as “Chancellor of the State Council” (中书门下平章事). Additionally, the role of Deputy Chancellor (参知政事) was introduced as a vice-chancellor, collectively referred to as “Chancellor and Deputy Chancellor” (宰执). The authority of the Chancellors significantly diminished, with their responsibilities limited to administrative functions. The State Council and the Privy Council (枢密院) jointly held administrative and military power. The government also established the Salt and Iron Superintendent, Household Ministry, and Financial Directorate (度支使) to manage financial matters, collectively known as the “Three Departments” (三司) or “Ministries of Control.” This system of checks and balances between the Three Departments, the Chancellors, and the Privy Council weakened the power of the Chancellors and strengthened the authority of the emperor. The Song Dynasty further expanded the surveillance system by adding institutions such as the Court of Remonstrance (谏院) and appointing Remonstrance Officials (谏官), which were responsible for impeachment and other oversight matters. Through these reforms, the emperor consolidated his power.

The Northern Song government implemented a system of decentralizing authority, where the Chancellor’s responsibilities were divided among multiple officials. Additionally, positions such as the Privy Councilor, the Financial Superintendent, and the Superintendent of War were introduced to distribute the military, political, and financial powers held by the Chancellor, effectively increasing the authority of the emperor.

The separation of official titles from actual duties was exemplified by the “Titles, Positions, and Appointments” (官、职、差遣) system. “Title” refers to an official designation, such as Shangshu (尚书) or Shilang (侍郎), primarily used for ranking and salary purposes; “Position” is an honorary title granted to certain civil officials without actual responsibilities, such as Scholar (学士) or Direct Attendant (直阁), and “Appointment” pertains to the actual duties undertaken by officials, also known as functional appointments, such as the Superintendent of War (枢密使) or the Financial Superintendent (三司使).

After the establishment of the Northern Song, the examination system was refined, the number of candidates admitted was increased, and the treatment of successful candidates was improved. This led to the inclusion of educated individuals from the landlord class in the political system. Starting from the later period of Emperor Taizu’s reign, the examination process required the “Palace Examination” (殿试) conducted by the emperor himself after passing the imperial examination conducted by the Ministry of Rites. This meant that those who passed both examinations became “Imperial Scholars” (天子门生).

During the Five Dynasties period, there was no comprehensive judicial system, and regional warlords acted with impunity, inflicting arbitrary punishment and death sentences. The Ministry of Justice was virtually ineffective. In the Song Dynasty, efforts were made to centralize judicial power, establish strict legal procedures, and require that all death sentences be submitted for central review and approval. This led to a partial restoration of the judicial system, with significant power consolidated at the central level.

Song dynasty economic system

Economic System Characteristics of the Song Dynasty

The economic system of the Song Dynasty was primarily characterized by two forms: state-controlled economy and private enterprise economy.

State-Controlled Economy:

The state-controlled economy in the Song Dynasty encompassed two main aspects: the monopoly system for tea and salt, and mining and manufacturing industries.

The tea and salt monopoly system was a significant economic policy of the Song Dynasty. Under this system, the government had exclusive rights to the production and sale of tea and salt, with prices determined by official regulations. This approach ensured both steady government revenue and stable quality and prices of these essential commodities. Additionally, the monopoly system provided a means for the government to regulate private economic activities.

Mining and manufacturing industries also played a crucial role in the state-controlled economy of the Song Dynasty. These industries received direct investment from the state, and the government encouraged private investment through fiscal support and tax incentives.

Private Enterprise Economy:

The private enterprise economy of the Song Dynasty encompassed three main sectors: agriculture, handicrafts, and commerce.

Agriculture formed the foundation of the Song Dynasty economy and constituted the largest sector by population. Technological advancements and increased productivity in agricultural production were pivotal to the economic prosperity of the era.

Handicrafts constituted another significant component of the economy. The Song Dynasty saw advancements in various handicrafts, including textiles, ceramics, woodworking, metalworking, and more. The scale and quality of handicraft production experienced significant improvement, becoming integral to the economy.

Commerce was one of the most vibrant sectors of the Song Dynasty economy. The growth of commerce was facilitated by improved transportation and the development of a currency-based economy. Commercial activities primarily occurred in marketplaces, with some traders engaged in maritime and river trade.

Thriving Trade:

The Song Dynasty is recognized as one of the periods of remarkable trade development in Chinese history. Favorable factors such as convenient transportation, active commercial activities, and high market demand contributed to unprecedented trade prosperity. Trade during the Song Dynasty mainly took the forms of maritime trade and overland trade. Maritime trade focused on the South China Sea and East China Sea, involving commodities such as tea, silk, and porcelain. Overland trade relied heavily on the Grand Canal, with commodities including grains, salt, iron, and timber.

Development of the Economic System in the Song Dynasty

Northern Song Period:

The Northern Song period was a crucial phase in the development of the Song Dynasty’s economic system. During this time, state-controlled economy underwent rapid growth, with state-operated commercial enterprises, iron smelting, and the tea industry becoming vital economic arteries. These state-controlled sectors played significant roles in economic control and advancement. Simultaneously, private enterprise economy gradually expanded, with handicrafts emerging as a pivotal component. Furthermore, the trade sector made swift progress, both in maritime and overland trade.

Southern Song Period:

The Southern Song period marked another significant phase in the development of the Song Dynasty’s economic system. During this time, state-controlled economy continued to evolve, with industries such as tea, salt, and iron solidifying their roles as economic pillars. Their influence on economic control and development became even more critical. Concurrently, both handicrafts and agriculture witnessed further growth in the Southern Song period, with silk manufacturing particularly emerging as a crucial facet of the economy. Moreover, the trade sector experienced heightened prosperity, achieving substantial accomplishments in both maritime and overland trade.

Influence of the Economic System of the Song Dynasty

The economic system of the Song Dynasty had profound effects on Chinese history and culture, primarily manifested in the following aspects:

Promotion of Economic Development:

The establishment and refinement of the economic system during the Song Dynasty provided strong support for the development of the Chinese economy. The simultaneous growth of state-controlled and private enterprises facilitated rapid economic advancement during this era. Concurrently, the prosperity of trade played a crucial role in driving economic growth.

Advancement of Commercial Culture:

The development of the economic system during the Song Dynasty created essential conditions for the rise of commercial culture. The flourishing of commercial activities and the associated culture became integral components of Song Dynasty culture. The commercial culture of the Song Dynasty had far-reaching impacts on China’s business development and cultural heritage.

Influence on Political System:

The establishment and refinement of the economic system during the Song Dynasty also laid the foundation for changes in the political system. The development of state-controlled enterprises strengthened the control of bureaucratic groups over economic affairs, thereby providing a significant backdrop for the evolution of the political system during the Song Dynasty.

Development of the Southern Economy

The economic development of the southern region during the Song Dynasty primarily encompassed two aspects: the advancement of agricultural production and the flourishing of commercial trade.

Advancement of Agricultural Production:

The climate and geographical conditions of the southern region were conducive to the growth of rice, making rice cultivation a predominant agricultural activity. Agricultural production in the southern Song Dynasty heavily relied on irrigation and water management projects. Through effective utilization of water resources, agricultural production in the southern region witnessed significant growth.

Technological progress also played a crucial role in enhancing agricultural production in the southern region. Technological advancements in rice breeding, field management, and fertilization contributed to substantial improvements in agricultural output. These technological advancements provided a solid foundation for the economic development of the southern region.

Flourishing Commercial Trade:

Commercial trade in the southern Song Dynasty was predominantly driven by maritime trade and inland waterway transportation. The establishment and development of port cities in the southern region facilitated maritime trade. Additionally, the expansion of inland waterway transportation greatly supported commercial activities in the south.

The prosperity of commercial activities in the southern region was closely linked to the development of monetary economy during the Song Dynasty. The growth of the monetary economy facilitated smoother commercial transactions. Furthermore, the government implemented policies such as tax incentives to encourage the growth of commercial activities.

Characteristics of the Southern Shift in the Economic Center of the Song Dynasty

The shift of the economic center southward during the Song Dynasty is characterized by the following aspects:

Transformation of the North-South Economic Pattern:

Before the Song Dynasty, the economic center of China had traditionally been in the northern regions. However, with the rise of the Southern Song Dynasty, the economic development in the south began to rapidly outpace that of the north, gradually replacing the north as the economic hub. The development of the southern economy was primarily driven by a series of economic policies implemented by the Southern Song government, such as fostering private enterprise, promoting a monetary economy, and encouraging overseas trade. These policies contributed to the continuous growth of the southern economy.

Development of Commerce and Handicrafts:

During the Southern Song period, commerce and handicrafts experienced rapid growth. Commercial centers were concentrated in the Jiangnan region, including cities such as Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Ningbo. These areas became bustling hubs of commerce, forming a market-centered economic system. The expansion of handicrafts was facilitated by government support and protection measures. The establishment of institutions like the Silk Monopoly Bureau and the Iron Goods Monopoly Bureau played a significant role in the flourishing of handicraft industries.

Expansion of Overseas Trade:

The Southern Song era witnessed substantial growth in overseas trade, largely due to government initiatives and the revival of the maritime Silk Road. The Southern Song government implemented a range of measures, including the establishment of maritime supervision agencies, maritime prohibition bureaus, and maritime taxation, which greatly facilitated the development of overseas trade.

Key Events Signifying the Southern Shift of the Economic Center during the Song Dynasty

The shift of the economic center southward during the Song Dynasty is marked by several significant events:

Capital Relocation to the South:

During the Southern Song period, as the northern economy declined and the southern economy rapidly developed, the Southern Song government decided to relocate the capital from Kaifeng to Lin’an. This event symbolized the rise of the southern economy and the decline of the northern economy, as well as the southward shift of the economic center of the Song Dynasty.

Introduction of a Monetary Economy:

In the Southern Song era, the government began to promote a monetary economy by issuing various forms of paper currency and copper coins. The circulation of these currencies greatly facilitated economic growth in the south. This event marked the transition of China’s economy from a barter system to a monetary economy and also signaled the southern shift of the economic center of the Song Dynasty.

Revival of the Maritime Silk Road:

During the Southern Song period, the government reopened the maritime Silk Road, leading to significant growth in China’s overseas trade. This event marked a shift towards maritime openness in China’s economy and also indicated the southern shift of the economic center of the Song Dynasty.

The Impact of the Southern Shift of the Economic Center during the Song Dynasty on China

The southern shift of the economic center during the Song Dynasty had several significant impacts on China:

Rapid Development of the Southern Economy:

The southern shift of the economic center led to the rapid development of the southern economy, making the southern region the center of China’s economy. During this period, the southern economy experienced significant growth in commerce, handicrafts, and overseas trade, contributing to its economic prosperity.

Gradual Decline of the Northern Economy:

The southern shift of the economic center resulted in the gradual decline of the northern economy, rendering the northern region a peripheral area in China’s economy. The northern economy mainly relied on agriculture during this time, and due to the rise of the southern economy, northern economic development was marginalized.

Opening of China’s Economy to the Seas:

The southern shift of the economic center led to the opening of China’s economy to the seas, as China began to establish the maritime Silk Road, facilitating exchanges and interactions between China’s economy and the world economy. Overseas trade witnessed significant growth during this period, integrating China into the global economy.

Transition to a Monetary Economy Era:

The southern shift of the economic center propelled China into the era of a monetary economy. China started implementing a monetary economy, issuing various forms of paper currency and copper coins, which contributed to the substantial growth of the economy. This transition marked China’s shift from a barter-based economy to a monetary economy, laying the foundation for economic advancement.

Song dynasty coins(Currency of Song Dynasty)

The Song Dynasty experienced a thriving economy, with commonly used currencies including copper coins and silver. During the reign of Emperor Taizong, the annual coinage amounted to 800,000 guan (a unit of currency). By the sixth year of Emperor Shenzong’s Xining era, the coinage had risen to over six million guan. The Song Dynasty witnessed the highest volume of coin production in ancient China, and it was also a period of remarkable stability and prosperity in the history of Chinese copper coin currency systems. Scholars estimate that the total amount of coinage during the Northern Song period reached 200 to 300 million guan. Due to the favorable reputation of Song copper coins, they were extensively smuggled to Southeast Asia and West Asia. Song people described the outward flow of copper coins as “heavy carts leaving the border, and ships laden returning.”

This extensive outflow of copper coins led neighboring countries such as Liao, Western Xia, Jin, Japan, Champa, and Goryeo to adopt the use of Chinese copper coins. In response, these countries also began producing their own versions of copper coins, creating an East Asian copper coin currency system.

As a consequence of the significant outflow of copper coins and silver, there was a shortage of hard currency. During Emperor Renzong’s reign, 16 wealthy households in Chengdu issued a form of paper currency called “jiaochao,” replacing iron coins in Sichuan. This marked the creation of the world’s earliest known paper currency. In subsequent reigns, the production of jiaochao was taken over by the government and issued at regular intervals.

Over time, the issuance of jiaochao increased, and they were used alongside copper coins. However, the continuous issuance of jiaochao led to its devaluation, and its exchange rate with copper coins declined. In 1160, during the 30th year of the Shaoxing era, the government established the “huizi” system, with huizi being based on copper coins. This system was divided into three categories: Southeast Hui, Hubei Hui, and Jianghuai Hui. Despite attempts to stabilize the exchange rate between huizi and copper coins, huizi continued to depreciate, causing significant inflation and leading to a phenomenon where huizi were exchanged for copper coins.

In 1210, during the 2nd year of the Jiading era, a currency crisis emerged, prompting the government to change the huizi system again. Although subsequent efforts were made to stabilize the currency, huizi continued to depreciate and eventually became practically worthless. This paper currency experiment ultimately faced challenges and failures, contributing to social upheaval and economic instability.

The extensive use of paper currency and the subsequent challenges it posed highlight the complexity of implementing and maintaining a stable monetary system during that time.

The currency of the Song Dynasty had several distinctive characteristics:

- The primary currency of the Song Dynasty was copper coins, supplemented by paper currency.

- There was a diverse range of currency types in the Song Dynasty, including “tongbao” (circulating treasure), “yuanbao” (primary treasure), and “zhongbao” (heavy treasure), among others.

- Song Dynasty currency was crafted with exquisite workmanship, with some coins even being considered as works of art.

- The circulation of Song Dynasty currency extended beyond its borders; it was not only used domestically but also circulated in regions such as Japan and Korea.

- The purchasing power of Song Dynasty currency was relatively stable. The government managed the currency’s purchasing power by regulating factors such as the quantity of currency in circulation and its velocity of circulation.

tribute system Song dynasty

The tributary system of the Song Dynasty had several characteristics:

Tributary trade served as the main channel for official trade between the Song Dynasty and foreign regimes. In this trade process, the Song government imposed strict limitations on the number of foreign envoy personnel, travel duration, routes taken, and the tribute items presented.

These restrictions on the number of envoy personnel were not aimed at a single country, but rather applied universally to various overseas nations such as Dashi, Zhunei, Sanfoqi, Shapo, Zhancheng, Danliumei, Boni, Guluomojia, and others. The Song Emperor Shen Zong rejected a request to increase the envoy personnel to three hundred, maintaining the traditional quota of seventy personnel for a foreign envoy. This limitation aimed to manage the economic costs associated with tributary trade.

Control over the duration of envoy groups staying in “China” was another method to save expenses. For instance, during the Yuan You reign, a decree specified that envoys from India were not allowed to stay beyond a hundred days. After the Southern Song Dynasty’s migration, the Huai River became the border between the Song Dynasty and other foreign entities, intensifying the sense of “China” as a defined space and leading to more stringent controls over envoys’ numbers and duration.

An example is seen in the rule that envoys from Sichuan could not exceed ten people and three hundred guan in goods at the Sizhou commercial center. This kind of strict control extended even to the lengths of stay of envoys. The tighter controls on foreign envoys and their duration were a reflection of the intensified awareness of the Southern Song’s territorial boundaries.

Furthermore, the Song Dynasty strictly prescribed the routes that foreigners could take upon entering “China.” The decree required Western countries such as Sha, Dashi, and others from the Western Regions to travel along the coast to Guangzhou before heading north. This decree aimed to prevent them from using the northwestern land routes. The Song government established this directive to ensure that these envoys followed the route specified and did not divert.

In addition to regulating the number of envoys and their routes, the Song Dynasty had regulations on the types of tribute items presented. The government prohibited unnecessary items, like frankincense, from being offered, as well as trading and bringing non-essential items to the capital. Despite these regulations, certain envoys violated the rules, leading to corrective measures, such as the withdrawal of undesired tribute items like frankincense.

The attitude of the Song Dynasty towards the tributary trade with various foreign states can be characterized as cautious, focused on minimizing expenses, safeguarding national secrets, and maintaining security. While the perspective presented by Huang Chunyan in “A Study of the Tributary System in the Song Dynasty” about limiting measures being driven by a desire to reduce reciprocal gifts and save on reception expenses is reasonable, there are deeper anxieties underlying the Song Dynasty’s approach.

In the 29th year of Shaoxing era, a statement from officials in the Imperial Secretariat sheds light on the mindset of the Song rulers and ministers. They expressed concerns about private trading among merchants that might result in losses of taxes and also feared the leakage of confidential information. This highlights two major concerns: loss of revenue and information leakage. As early as the second year of the Xianping era (998), during the Northern Song, the statesman Suo Xiang had expressed concerns about the mingling of spies and deceptive individuals among the merchants traveling between the Song and Liao states. This demonstrates a worry about potential enemy agents infiltrating trade routes.

This sense of vigilance extended to the validation of the official identities of tributary envoys. During the reign of Emperor Shenzong, it was stipulated that envoys from the country of Tiaozhi (modern-day Vietnam) must bring a royal letter and appropriate offerings. This practice continued with later dynasties, including checks on the credibility of emissaries from Goryeo (Korea). This official validation conveyed a message of confidence and control over interactions with foreign entities.

Despite the various restrictions and official validations in place, the Song rulers remained uneasy, fearing that valuable items and important documents might be stolen or fall into the hands of foreign powers. Materials concerning politics, military affairs, diplomacy, and potentially transformative technological knowledge were strictly guarded. The state prohibited the export of books, military equipment, and provisions. This approach was understandable considering the geopolitical context of the time, where neighboring states were seen as potential adversaries or competitors.

Furthermore, products of luxury such as silk and brocade were also restricted from being traded in certain contexts. The decree of the second year of Jingde era (1005) prohibited trading silk and fine fabrics at border marketplaces, with Emperor Zhenzong explaining that these items were meant for ceremonial purposes and the fear was that they would be traded with the northern neighbors (Liao). This reveals a complex interplay between the Song’s reverence for ritual and symbolism and their somewhat disdainful attitude towards neighboring cultures.

song dynasty flag

The Song Dynasty utilized various types of flags for different purposes, including military marches, battles, ceremonial processions, educational activities, and bestowals. These flags included dragon flags, phoenix flags, black flags, white flags, bagua (eight trigrams) flags, and tiger-leopard flags.

The flags of the Song Dynasty were exquisitely crafted and followed a specific set of rules regarding quality, quantity, and design. They came in five main colors: yellow, white, red, black, and blue. Yellow flags were reserved for the emperor, white flags for generals, red flags for the three armies, black flags for the imperial guard, and blue flags for vanguards.

Apart from these five color-based flags, the Song Dynasty also used specific flags for various purposes:

Dragon Flags and Phoenix Flags: Dragon flags were exclusively used by the emperor and came in two types: white dragon flags and blue dragon flags. Phoenix flags were used by the empress.

Black Flags and White Flags: These flags were used for the protection of the emperor.

Bagua Flags: These flags featured the eight trigrams of the I Ching (Book of Changes) and were employed to convey military orders.

Tiger-Leopard Flags: These flags were used for protecting the emperor and as guards.

It’s important to note that the concept and use of flags during the Song Dynasty were different from modern national flags. Flags were used as symbols of authority, hierarchy, and coordination in various contexts, especially within the military and imperial ceremonies.

song dynasty history

Founding of the Song Dynasty

In the sixth year of Xiande during the Later Zhou dynasty (959 AD), Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou, Chai Rong, passed away, and his young son, Emperor Gong of Later Zhou, Chai Zongxun, ascended the throne. Before his death, Emperor Shizong took measures to prevent a coup by relieving the commander of the imperial guards, Zhang Yongde, of his military position and appointing Zhao Kuangyin to replace him. Zhao Kuangyin, who had previously served under Guo Wei, earned recognition for his military achievements and gained trust and prominence within Later Zhou. In the seventh year of Xiande (960 AD) in the first month, on the first day of the month, news arrived from the northern borders that the Khitan-Later Han alliance had invaded. In reality, prime ministers Fan Zhi and Wang Pu, who were effectively managing the court, decided to order Zhao Kuangyin to lead the imperial guards to confront the invaders. When Zhao Kuangyin marched to Chenqiao Relay Station in the northern suburbs of Kaifeng, his subordinates draped him in a yellow robe and proclaimed him emperor, an event known as the “Chenqiao Mutiny.” Zhao Kuangyin swiftly and bloodlessly seized control of Later Zhou, establishing the Song dynasty, also known as the Northern Song, with its capital remaining in Kaifeng, referred to as Dongjing. Zhao Kuangyin became Emperor Taizu of Song.

Following his imperial ascension, Emperor Taizu first quelled rebellions by former officials Li Yun and Li Chongjin to consolidate Northern Song’s rule over the territories formerly under Later Zhou. He devised a strategy of “South First, North Later” to gradually unify the nation. To counter threats from the north, such as the Khitans (Liao), Beihan, and Xixia tribes, Emperor Taizu stationed military commanders along the northern borders, ensuring security and focusing efforts on unifying the southeast.

In the first year of Qiande (963 AD) in the first month, under the pretext of suppressing a rebellion by Zhang Wenbiao in Wuping, Hunan, Emperor Taizu led an army through Jingnan. As the Song forces approached, the military governor of Jingnan, Gao Jichong, surrendered, marking the first elimination of a separatist regime. The Song army swiftly advanced south, annexing Hunan as well. This action severed the connections between Southern Tang, Southern Han, and Later Shu, laying the groundwork for future victories. In the second year of Qiande (964 AD), towards the end of the year, Emperor Taizu initiated an attack on Shu (Later Shu), successfully compelling its emperor, Meng Chang, to surrender in just over two months. By the end of the third year of Kaibao (970 AD), Song forces extended their control to Xingwangfu, toppling Southern Han and incorporating parts of Guangdong and Guangxi.