The Chinese bow and arrow is one of the significant ancient military and hunting tools in China, as well as an essential component of Chinese traditional culture. Its history can be traced back to the Neolithic Age, spanning approximately 7,000 years. The evolution of Chinese bows and arrows is closely intertwined with advancements in warfare and military technology, gradually becoming a primary weapon for the Chinese military and playing a crucial role in warfare.

what are the Chinese bow and arrow?

The bow and arrow is a long-range weapon with significant power and range. The bow consists of flexible limbs and a resilient string, while the arrow comprises an arrowhead, shaft, and feathers. The arrowhead is typically made of copper or iron (modern arrowheads are often alloy), the shaft is constructed from bamboo or wood (modern versions are primarily carbon or aluminum alloy), and the feathers are sourced from vultures, eagles, or geese. It is an important weapon used by both military forces and hunters.

what is a Chinese bow called?

The bow and arrow, also known as a string bow, longbow, short bow, reflex bow, crossbow, etc., is a weapon that uses elasticity to shoot arrows. It was widely used in ancient China and played a significant role in warfare. Additionally, the bow and arrow are commonly used tools in hunting and sports competitions.

In ancient times, the bow and arrow were also referred to as “Wu Hao.”

“The Records of the Grand Historian” recorded: “The Yellow Emperor made a bow to catch fish and birds.” Ancient people referred to the bow and arrow as “Wu Hao,” and particularly used the term “Wu Hao” to describe bows and arrows of excellent quality.

An arrow, also known as a shaft, is a long-range weapon with a sharp edge that is launched using mechanical force from a bow or crossbow. Due to differences in launching methods, arrows are divided into bow and arrow, crossbow bolt, and throwing arrow. Arrows used with bows are longer, approximately 70 centimeters in length, while those used with crossbows are shorter, around 50-60 centimeters. An arrow is composed of three parts: the arrowhead, arrow shaft, and arrow feathers. The arrowhead, also known as an arrowhead tip, is often made of iron and features a sharp tip and a fuller base. Arrowhead styles include triangular, diamond-shaped, and conical.

Ancient bows were known by various names:

Bow and crossbow: General terms for various types of archery equipment in ancient times, including the divine arm bow, Kunlun bow, thunderbolt bow, etc.

Dàgōng: Refers to the arm used to make bows in ancient times and later became a term for a bow.

Sānghú: A bow made from mulberry wood, which became a general term for bows.

Besides the aforementioned terms, ancient bows had other names, such as “dàn,” “qiáng,” “jìn,” and “gòu.”

what is the Chinese symbol for bow and arrow?

The Chinese symbol for “bow and arrow” is 弓箭 (gōng jiàn). The character 弓 (gōng) represents “bow,” and the character 箭 (jiàn) represents “arrow.” When combined, these two characters form the term for “bow and arrow” in Chinese.

who invented bows and arrows?

The bow and arrow are believed to have originated in Africa, which is a widely accepted viewpoint. Humans were already using this technology during the Howiesons Poort phase of the Middle Stone Age in Africa. This phase spans approximately from 37,000 to 65,000 years ago. However, the origin and spread of the bow and arrow are not fully documented in historical records.

Recent archaeological findings from the Pinnacle Point Cave in South Africa provide new evidence, suggesting that the earliest use of bows and arrows can be pushed back to around 71,000 years ago. This discovery indicates that bow and arrow technology existed as early as the Late Paleolithic or the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Nevertheless, there is currently no evidence to suggest that bow and arrow technology was used by humans outside of Africa until around 15,000 to 20,000 years ago.

Therefore, while Africa is considered the likely birthplace of the bow and arrow, there remain many unknowns about the specific development and spread of this technology. As archaeological and historical research continues to advance, we may gain a deeper understanding of the origin and dissemination of the bow and arrow.

where did bows and arrows originate from in China?

The origin of the bow and arrow dates back to China, where ancient Dongyi people were among the earliest inventors and adept archers.

In the Longshan Culture period, spanning from around 4600 to 3300 years ago, inscriptions resembling the shape of a person with a bow, and the character “夷” (meaning “barbarian” or “archer”), provide primitive evidence for the concept.

Before the establishment of the Qi state by Jiang Taigong in 1045 BCE, a Dongyi tribe thrived in the Qi region. Expert analysis suggests that bows and arrows emerged in China approximately 28,000 years ago, making it the earliest inventor of these tools in the world.

During the era of primitive fishing and hunting tribes, gradual improvements were made to hunting equipment. Initially, they fought wild animals barehanded, later learning to throw stones and clods. The earliest arrows were simple and might have originated from spears, which ancestors later reduced in size to create arrows that could be used with bows. These consisted of a stick or bamboo shaft cut to a certain length and sharpened at one end.

The true origin of the arrowhead likely dates back to the Stone Age in primitive societies. People crafted pointed shapes from stones, bones, or shells, attaching them to the end of arrow shafts, creating stone or bone arrowheads. This marked a significant advancement compared to arrows solely crafted from wooden sticks or bamboo. Eventually, they harnessed the elasticity of branches to invent slingshots and, ultimately, bows.

The earliest civilizations to equip themselves with bows and arrows were in Egypt. During the Ancient Kingdom period, the Egyptian military primarily employed battle axes and bows and arrows. The arrowheads at the time were made of stone, gradually replaced by copper. The ancient Egyptians of the Fifth Dynasty referred to neighboring groups such as the Nubians, Libyans, and Asians as the “people of the nine bows,” indicating that these societies were also equipped with bows and arrows. Among the earliest civilizations, the archer units of Pharaoh Sargon I were renowned, striking fear into the hearts of surrounding enemies. Most other civilized nations and even some barbaric tribes adopted bows and arrows, with few exceptions such as the indigenous Australians and Aleutians.

bows and arrows history in china

Although the bow and arrow is believed to be one of the earliest inventions of humankind, the exact origin and earliest inventor of the bow and arrow remain unclear. The use of the bow and arrow may trace back to ancient mythological times. The well-known legend of Houyi shooting down the nine suns is one of the most famous examples showcasing the power of the bow and arrow.

In human sites dating back to around 100,000 years ago, such as the Shizhu Paleolithic site in Shuoxian, Shanxi Province, China, arrowheads made of stone have been discovered. These arrowheads had one end sharpened and the other end slightly narrower, designed for attachment to an arrow shaft.

At that time, arrows were quite simple, often made from natural tree branches or bamboo segments, with one end sharpened to form the arrowhead. Gradually, stone, bone, or shell materials were shaped into sharp arrowheads, marking a significant advancement in lethality compared to simple pointed sticks. However, due to the preservation challenges of bamboo or wooden arrow shafts over thousands of years, only stone arrowheads from that time period are typically found in archaeological excavations.

China has a long history of using bows and arrows. Stone arrowheads dating back to around 28,900 years ago were discovered in the Zhiyu site in Shuoxian, Shanxi Province, providing evidence that bows and arrows were already in use in China over 28,000 years ago.

In the later stages of the Neolithic period, approximately 10,000 years ago, a variety of arrowhead shapes, including barbed, leaf-shaped, and triangular, were found in human sites. Some arrowheads even had stems or backward-facing barbs, making it difficult for animals to escape once hit.

The earliest recovered bow in China is a lacquered bow from the Kuahuqiao site in Zhejiang Province, with a length of 121 centimeters and estimated to be around 8,000 years old.

During the Xia and Shang dynasties, bronze arrowheads appeared. The Erlitou Culture site in Yanshi County, Henan Province, dating back to around 3,800 to 3,500 years ago, yielded the earliest known bronze arrowheads from the Shang Dynasty, primarily featuring double-winged spines.

In the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, the main styles of arrowheads were three-sided. Following the Western Han Dynasty, iron arrowheads became more common to save on copper usage.

The use of bows and arrows was widespread during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, and archery was a skill that nobles and officials had to master. Archery was not only a ritual at state meetings and banquets but also held cultural significance in daily life.

In the Tang Dynasty, there were four main types of bows: the yellow birch bow, black lacquer bow, white birch bow, and hemp-backed bow. The Song Dynasty also valued bows and arrows, with bows being categorized into four types.

During the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, recurved Turkic bows with pronounced curves and finger rings were used, requiring a unique method for stringing. In the Ming Dynasty, bows were carefully crafted using materials from various regions, with smaller-sized bows being the mainstream choice.

In the Qing Dynasty, the composite recurve Turkic bow was replaced by heavy bows and long arrows with armor-piercing capabilities. The Qing Dynasty’s heavy bows developed from previous iterations, featuring a length of up to 1.8 meters and a draw weight of over 70 kilograms.

Throughout China’s history, the use and significance of bows and arrows evolved and diversified with changes in dynasties and cultures, forming a rich and diverse ancient Chinese archery culture that enriched both material and intangible cultural heritage.

when was Chinese bow and arrow invented?

Approximately 30,000 years ago, humans in the territory of China began using bows and arrows. The earliest arrows were quite simple, crafted by cutting a tree branch or bamboo into a specific length for the arrow shaft, and sharpening one end to form the arrowhead. The true origin of the arrowhead dates back to the primitive stone age when people shaped stones, bones, or shells into sharp forms and affixed them to one end of an arrow shaft, creating stone, bone, or shell arrowheads. This was a significant advancement compared to using simple wooden sticks or bamboo for arrows.

Since ancient arrow shafts are difficult to preserve over time, often only arrowheads have survived in archaeological finds. During the Neolithic period, stone, bone, and shell arrowheads were discovered, featuring various shapes such as stick-like, leaf-like, and triangular, with some having stems and backward-facing barbs. The earliest discovered bronze arrowheads from the early Shang Dynasty were found at the Erlitou site in Yanshi County, Henan Province. During the Shang and Zhou periods, the primary style of bronze arrowheads was the double-winged spines.

In the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, the triangular-style arrowheads with three sides were prevalent, many of which were fitted with iron tips during the Warring States period to conserve copper. After the Han Dynasty, there was a transition from bronze to iron arrowheads, a process that took about 200 years. Early Western Han Dynasty arrowheads found in Hebei Province were still molded, and their sharpness was not on par with bronze arrowheads. Conversely, flat, sharp-edged triangular iron arrowheads from the Eastern Han Dynasty, discovered in locations like Muma Mountain in Xin Fan County, Sichuan Province, were suitable for forging and possessed greater lethality. This shape became the basis for the subsequent use of pointed steel arrowheads.

who invented the bow and arrow in China?

The “bow and arrow,” as a type of cold weapon, is said to have been invented by “Hui,” the grandson of the Yellow Emperor. He held the official position of “Gong Zheng,” overseeing the production of bows and arrows. According to legend, it was the invention of the “bow and arrow” by Hui that contributed to strengthening the power of the Yellow Emperor’s regime. It was said that the use of “bow and arrow” played a role in the Yellow Emperor’s victory over Chi You. Hui is also considered the ancestor of the Zhang surname, as he invented the “bow,” and thus the name Zhang is composed of characters representing “bow” and “long.”

The invention of the bow and arrow by Zhang Hui is as follows: The leader of the Li tribe, Chi You, rebelled and oppressed the people, refusing to obey the orders of the Yellow Emperor. In response, the Yellow Emperor led his army and joined forces with various vassals to engage in fierce battles with Chi You on the plains of Zhuolu. However, after several defeats, the Yellow Emperor was greatly frustrated and ordered Zhang Hui to create weapons to assist in the war. During the night, Zhang Hui observed the arc-shaped stars and was inspired by their shape. This led him to invent the bow and arrow, which was used to aid in the war. With the Yellow Emperor’s army utilizing the bow and arrow, they became unstoppable in battle. The Chi You army was defeated and driven into the sea, ultimately leading to Chi You’s demise at the hands of the Yellow Emperor.

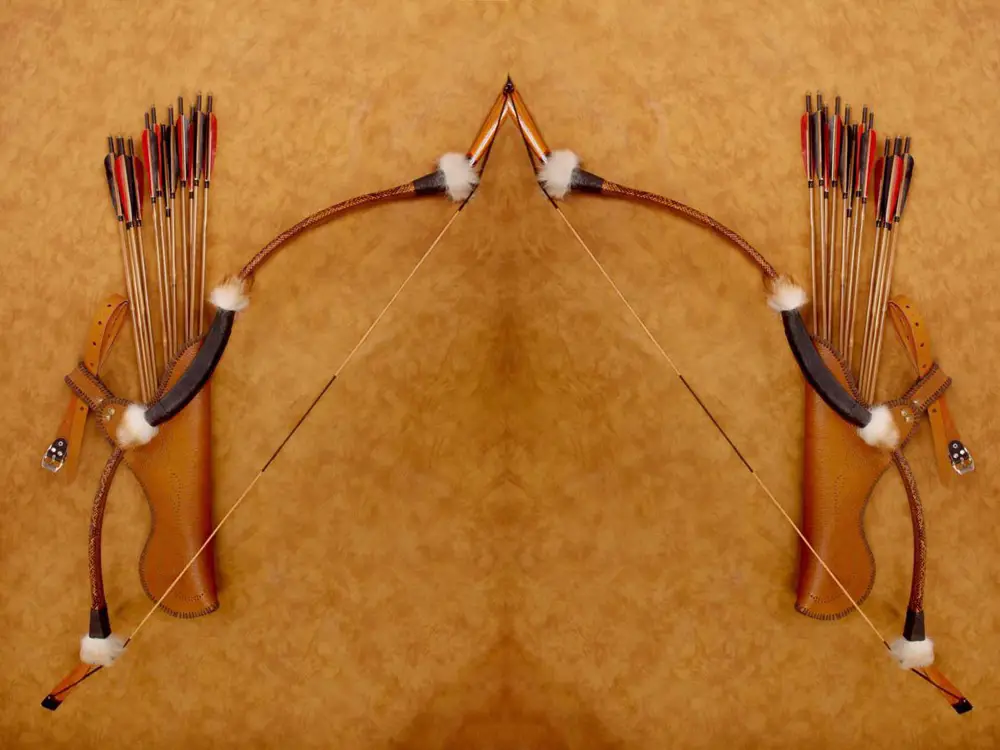

Chinese bow and arrow look like

Chinese bows and arrows have evolved over time, and their appearance has varied depending on the historical period and regional styles. Here, I’ll describe the general characteristics of traditional Chinese bows and arrows:

Chinese Bow:

Traditional Chinese bows are known for their distinctive design, often characterized by their asymmetrical shape and recurved tips.

The limbs of the bow curve slightly forward, creating a recurved shape that increases the power and efficiency of the bow.

The central grip of the bow is often narrow and may be adorned with decorative elements.

Chinese bows are typically made from materials such as wood, bamboo, horn, and sinew. The combination of these materials contributes to the bow’s strength and flexibility.

The length and draw weight of Chinese bows can vary, with some historical bows being quite long and powerful.

Chinese Arrows:

Traditional Chinese arrows usually consist of three main parts: the arrowhead, arrow shaft, and fletching.

Arrowheads were made from various materials throughout history, including stone, bone, bronze, and iron. They could be of different shapes, such as triangular, leaf-shaped, or barbed.

The arrow shafts were often made from bamboo or wood. The length and thickness of the shafts could vary based on the type of bow and the purpose of the arrow.

Fletching, which provides stability and balance during flight, is typically made from feathers. These feathers are attached to the back end of the arrow shaft.

Chinese arrows were designed for different purposes, including hunting, warfare, and archery competitions. Some arrows were specialized for armor-piercing, while others were optimized for long-range accuracy.

It’s important to note that there were variations in bow and arrow designs across different Chinese regions and historical periods. The description above provides a general overview of traditional Chinese bow and arrow characteristics, but specific details may vary.

structure of bow and arrows

The bow consists of several parts: the bow tip, bow limbs, handle (or grip), and string pad, each serving different functions:

- The bow tip is primarily responsible for holding the bowstring, often made from hardwood or animal horn. Single-piece bows usually lack bow tips.

- The bow limbs are the crucial energy-storing components of the bow. In a composite bow, they are constructed by bonding wood and animal horn using animal glue. Single-piece bows typically consist of an all-wood construction. Consequently, composite bows generally exhibit superior energy storage compared to single-piece bows of the same length.

- The handle (or grip) is where the archer holds the bow. It provides support and is usually the thickest part of the entire bow.

- The string pad dampens vibrations of the bowstring during release, enhancing accuracy, and also offers protection to the bowstring. Some types of composites, like the Hungarian bow, do not have string pads, while single-piece bows generally lack them.

The earliest bows were crafted from a single piece of wood or bamboo, bent into shape and bound with animal tendons, leather strips, or hemp to create the bowstring. The initial arrows were simply sharpened slender sticks or bamboo rods, as described in the “Xici Xia” section of the Book of Changes (Yi Jing): “Using wood for the bow, and reeds for the arrows.”

Composite bows consist of three components: wood, horn, and sinew. The unstrung composite bow curves outward, with the bow back (facing the target) made from wood. The bow back includes three parts: a pair of limbs and a siyah. Wood components are often made from maple, barberry, or mulberry trees, sometimes employing multiple types of wood.

The bow face (facing the archer) is made of horn, which reinforces the limbs. Water buffalo horn is popular due to its elasticity and length, making it a preferred choice.

Bowstring is created from animal sinew, horsehair, or grapevine. Sogdians even used cow intestines to make bowstrings. The Turks, on the other hand, were renowned for their use of silk-made bowstrings.

Arrows in China mostly have pointed heads, distinct from the socketed arrowheads prevalent in Europe. Historians suggest this design was for self-defense. If the arrowhead were simply inserted into the shaft, it would decrease the shaft’s ability to absorb impact, making it prone to breaking. This design allowed horse archers to prevent adversaries from using their own arrows against them.

Arrow shafts are typically made from reed stalks or bamboo, with white birch and barberry wood also used. Arrow fletchings are crafted from waterfowl feathers, such as goose and duck feathers, for optimal stability during flight.

Drawstring tools:

Horse archers wear thumb rings (also known as draw or thumb guards) to prevent the bowstring from cutting the thumb. To enhance the speed of shooting, the inner side of the thumb ring often has a groove or indentation to secure the bowstring.

Bow quivers and arrow holders:

Sogdian horse archers combine a bow quiver and an arrow holder in a bag called a “gorytos.” The front of the gorytos has a pouch specifically for arrows. Sogdian horse archers suspend the gorytos from their belts using hooks. Early Samaritans also used this design.

what are Chinese bow and arrow made of?

During the Spring and Autumn period, the “Kaogongji” (Records of the Grand Historian on Crafts) contained a dedicated chapter titled “Bowmaking,” providing a detailed summary of bow-making techniques. Over the subsequent two millennia, Chinese and Asian composite bow manufacturing techniques remained fundamentally unchanged compared to the “Kaogongji.” The “Kaogongji” provided detailed requirements and specifications for the selection and processing of bow materials, the performance of components, and their assembly. It also analyzed potential defects in the crafting process. The “Kaogongji” regarded the “Six Materials” – dry wood, horn, sinew, glue, silk, and lacquer – as crucial.

Dry Wood (Gan):

“Dry wood” includes various types of wood and bamboo used to create the main body of the bow limbs, often layered. The performance of the dry wood decisively influences the bow’s performance. The “Kaogongji” specifies that zhe wood is the best, followed by yi and zuo trees, with bamboo being less favorable. These materials are extremely durable, resistant to bending, and capable of long-range and powerful shots.

Horn (Jiao):

“Horn” refers to animal horn, crafted into thin strips and attached to the inner side (belly) of the bow limbs. According to the “Kaogongji,” the preferred choice for bow-making is ox horn, with the best quality from the base, middle, or upper sections of the horn, each corresponding to different colors and qualities. These sections are humorously referred to as “ox wearing an ox” (meaning that a single horn costs as much as an ox itself). In northern China, yellow oxen were common, so sheep horns were used as a substitute, which became a strength of southern bows.

Sinew (Jin):

“Sinew” refers to animal tendons attached to the outer side (back) of the bow limbs. Both sinew and horn reinforce the bow limbs’ elasticity, resulting in faster and more penetrating shots. The “Kaogongji” notes that ox sinew is the most commonly used material. Selection of sinew should favor smaller, longer strands and larger, round and smooth ones.

Glue (Jiao):

“Glue” refers to animal glue used to bond dry wood and horn sinew. The “Kaogongji” recommends six types of glue: deer glue, horse glue, ox glue, rat glue, fish glue, and rhinoceros glue. Glue was prepared by boiling animal skin and tissue in water or with a small amount of lime, then filtering and condensing. Subsequent generations of bow-making experts found that fish glue derived from yellow croaker bladder was superior. Chinese bowmakers used fish glue for critical areas that required strength and used animal skin glue for less important parts, such as surface wrapping.

Silk (Si):

“Silk” refers to silk thread used to tightly wrap the horn-sinew-covered bow pipe, ensuring firmness. According to the “Kaogongji,” silk should have a bright luster, resembling water when submerged.

Lacquer (Qi):

“Lacquer” involves applying lacquer to the finished bow limbs to protect against moisture, frost, and dew. Generally, lacquer was applied every ten days until the bow limbs were sufficiently protected.

what are Chinese bow and arrow used for?

The ancient Chinese bow and arrow had various uses:

Hunting: The bow and arrow were essential tools for hunting, serving as crucial weaponry for both military and hunters.

Defense: During ancient times, bowmen could engage in concentrated shooting during city defense or siege warfare, slowing down enemy advances and protecting strongholds or defensive lines.

Training: Archery was a significant skill in ancient China, considered one of the “Six Arts” of a gentleman. It symbolized social status and refinement.

Ranged Projectile Weapon:

The bow and arrow offered significant advantages as a ranged projectile weapon. Firstly, its long range allowed attackers to engage enemies from a safe distance. Secondly, its rapid rate of fire enabled continuous shooting, creating a dense arrow barrage to pressure opponents. Thirdly, its strong penetrating power could breach armor, inflicting fatal injuries. As a result, bows and arrows were extensively utilized in ancient warfare as a primary ranged weapon.

Tactical Application:

Bows and arrows played a vital role in tactical applications. Archers could use terrain and cover for ambushes, delivering unexpected blows to the enemy. Archers could also cooperate with other units, forming a network of firepower. For instance, during cavalry charges, archers provided rear support, weakening the enemy’s momentum. Additionally, archers could control the battlefield with arrow showers, forcing enemies to alter their tactics. Thus, bows and arrows provided tactical versatility, adapting to changing battlefield conditions.

War Strategy:

Bows and arrows were significant in war strategy. Nations or factions with skilled archers gained advantages in battles. Ample supply of arrows and bowstrings was another advantage. For example, England’s longbowmen in medieval times were renowned for their powerful and sustained firepower, contributing to English victories. Effective strategy and tactics were crucial for utilizing bows and arrows in warfare. Roman armies, for instance, combined archers’ firepower with infantry charges, creating a potent fighting force. Therefore, bows and arrows held strategic and tactical value, influencing the outcome of wars.

Arrow Book Shooting:

Arrow book shooting is an ancient and mystical skill that not only tests archers’ accuracy and strength but also serves to protect and transmit knowledge through books. Its history dates back to ancient China, where scholars used this method to safeguard books. The concept is straightforward: arrows are shot through books, piercing their pages without damaging the book’s structure or content. This technique not only safeguards books but also transmits knowledge through the arrow’s trajectory.

Archery Marriage:

Archery marriage is a traditional wedding custom of the Yugur people in China, where the groom shoots arrows at the bride as a symbolic act to dispel negative energy and ensure a happy marriage. Once the bride enters the bridal chamber, the groom, holding a bow and arrow, shoots three arrowheads-less arrows at the bride. He then breaks these arrows, symbolizing the removal of negative energy. During this process, neither the groom nor the bride speaks to avoid offending each other. Archery marriage is not just a wedding custom but also a cultural expression and inheritance. Through this tradition, the Yugur people convey respect and blessings for marriage, wishing happiness and fulfillment for every couple.

Selecting a Spouse with Arrows (雀屏中选):

Selecting a spouse with arrows, also known as “queping zhongxuan,” is an ancient Chinese method of selecting a spouse through archery. This practice originated from a line in the “Shijing” (Book of Songs), specifically the “Zhao Nan” chapter, describing a love story involving shooting at magpie nests. Over time, this evolved into an idiom. In ancient China, when a woman was in seclusion, two paper magpies were cut out on a screen. Suitors would shoot arrows at the magpies, and whoever hit both magpies became the woman’s husband. This tradition gradually transformed into a cultural expression and symbolized reverence and blessings for marriage. In traditional Chinese culture, marriage is a significant event that requires careful consideration. Through the practice of selecting a spouse with arrows, people emphasized the importance of marriage and expressed their good wishes. In essence, “queping zhongxuan” was an ancient method of selecting a spouse and a cultural expression that conveyed respect and blessings for marriage. An example of this practice is found in the story of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty, who married Empress Dou by hitting the two magpies.

how does bow and arrow work?

The bow and arrow utilize the principle of elastic potential energy, combining human strength with the elasticity of materials to propel an arrow towards a distant target, achieving the objective of striking and killing the intended object.

The invention of the bow and arrow represents a significant advancement in human technology, demonstrating an understanding of storing energy through mechanical means. When force is exerted to draw the bowstring, energy is stored within the bow’s structure. Upon release, the bow rapidly returns to its original state, releasing the stored energy forcefully and propelling the arrow, which is nocked on the string, with great speed.

Arrow shafts were often made from bamboo or wood. In ancient times, “kuzhi” arrows were produced during the Pre-Qin period. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, bamboo shafts were used in southern China, while “ruisage” (a type of willow) was used in the north. In the northeastern and northwestern regions, birch wood was common. To enhance accuracy, feathers were attached to the rear of the arrow shaft, improving stability and flight control. The flight speed and accuracy of an arrow were closely related to the design of its tail feathers. An appropriate balance between too many and too few feathers was necessary for optimal performance. The “Kao Gong Ji” (“Records of Examination of Crafts”) provides methods for determining the lengths of various arrow components to achieve the desired tail feather proportions. Among feathers, wing feathers (plumage) were preferred, followed by eagle feathers, and then owl feathers. Arrows fletched with goose or swan feathers were prone to deviation in flight, resulting in inferior quality. During the Song Dynasty, when high-quality feathers were scarce, “fengfei” (wind feathers) arrows were developed. These arrows featured a design with a hollow groove at the tail end, which created a vortex resistance to stabilize flight. The concept behind this design was scientifically sound.

To increase the arrow’s lethality, “dujian” (poisoned arrows) were invented during the Later Han Dynasty. The novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” describes a scenario in which the arrowhead was poisoned. This innovation introduced a high risk of disability or death. With the advent of metal armor, arrows required increased penetration power. The Jin Dynasty saw the use of steel arrowheads. During the Tang Dynasty, arrows were categorized into bamboo, wood, military, and crossbow arrows. The latter two were used in combat, featuring steel arrowheads with longer blades for armor penetration. Apart from poisoned arrows, there were also “huo jian” (fire arrows) in ancient China, where combustible substances like oil or gunpowder were attached to the shaft, commonly used in warfare.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, “mingdi” (whistle arrows) were developed, with small whistles made from bone or animal horn attached to the arrowheads. The evolution of arrows paralleled improvements in bows and crossbows, with the emergence of powerful weapons demanding increased arrowhead quality.

types of Chinese bow and arrow

There are various types of bows in China’s history, including the Wang Bow, Hu Bow, Jia Bow, Geng Bow, Tang Bow, and Da Bow during the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States period. Among these, the Wang Bow and Hu Bow were used for defending cities and chariot warfare, while the Jia Bow and Fei Bow were used for hunting and shooting birds. During the Han Dynasty, bows like the Hu Jia Bow, Diao Bow, Jiao Duan Bow, Lu Bow, and Jiang Bow emerged. In the Tang Dynasty, there were also four types of bows and arrows: the Chang Bow (used by infantry), Jiao Bow (used by cavalry), Shao Bow, and Ge Bow (used by imperial guards).

Bow types include traditional bows, Mongolian bows, longbows, Chinese crossbows, arm-draw crossbows, foot-stirrup crossbows, waist-actuated crossbows, repeating crossbows, back-mounted crossbows, nitrate crossbows, and concealed crossbows, among others. Traditional bows have a long history in China and were used extensively in ancient military conflicts, reflecting their crucial role in warfare.

Xiongnu Bow and Arrow

The Xiongnu bow and arrow is a characteristic steppe composite bow. The draw weight of Xiongnu cavalry bows typically ranged from 20 to 30 kilograms. These bows had a maximum range of 100 meters, but in practical combat, the effective killing range for Xiongnu horse archers was usually around 40 meters. When facing armored Han soldiers, this range would further decrease to 20-30 meters to penetrate armor gaps. The Xiongnu’s significant innovation was the invention of “mingdi” (whistle arrows), which produced sound upon flight due to the air friction, combining lethality and signaling capabilities.

The Xiongnu resonant arrow, also known as the “sounding arrow” or “mingdi,” was a practice arrow used by the Xiongnu people. It featured a fine thread attached to the arrow shaft and tied to a pouch at the arrow’s tail. This design created a distinctive sound when the arrow was shot, hence its name. The resonant arrow served various purposes, including training, command, and communication within the Xiongnu culture.

In historical records like the “Records of the Grand Historian,” it is documented that Modu Chanyu, a Xiongnu ruler, invented a special kind of resonant arrow called the “mingdi” to train his cavalry. He commanded his cavalry to shoot in accordance with the sound of his own mingdi arrows, ensuring discipline and coordination.

The resonant arrow, or “mingdi,” had both military and practical applications among the Xiongnu people. It was used not only as a signal for commanding troops during warfare but also as a means of coordinating actions and movements of Xiongnu riders. The resonant arrow’s unique sound served as a distinctive signal on the battlefield.

Additionally, the resonant arrow was employed in hunting activities. Modu Chanyu and others used resonant arrows to shoot and hunt flying birds and animals. Once hit, the distinctive sound of the resonant arrow signaled the hunting party to move in for the capture.

In Xiongnu culture, archery held significant importance, and the resonant arrow was a distinctive tool associated with this skill. After the Han Dynasty, the use of resonant arrows gradually spread among the Han Chinese and became more widely adopted, marking a transition from being an exclusive symbol of the Xiongnu people.

Mongol Bow and Arrow

The Mongol bow and arrow are integral to Mongolian traditions, particularly in horsemanship. After the unification of the Mongols under Genghis Khan, archery skills evolved from hunting to combat usage. The draw and release techniques were practiced extensively to fend off external threats and protect herds from predators. Whistling arrows were also used among the Mongols, similar to the Xiongnu practice.

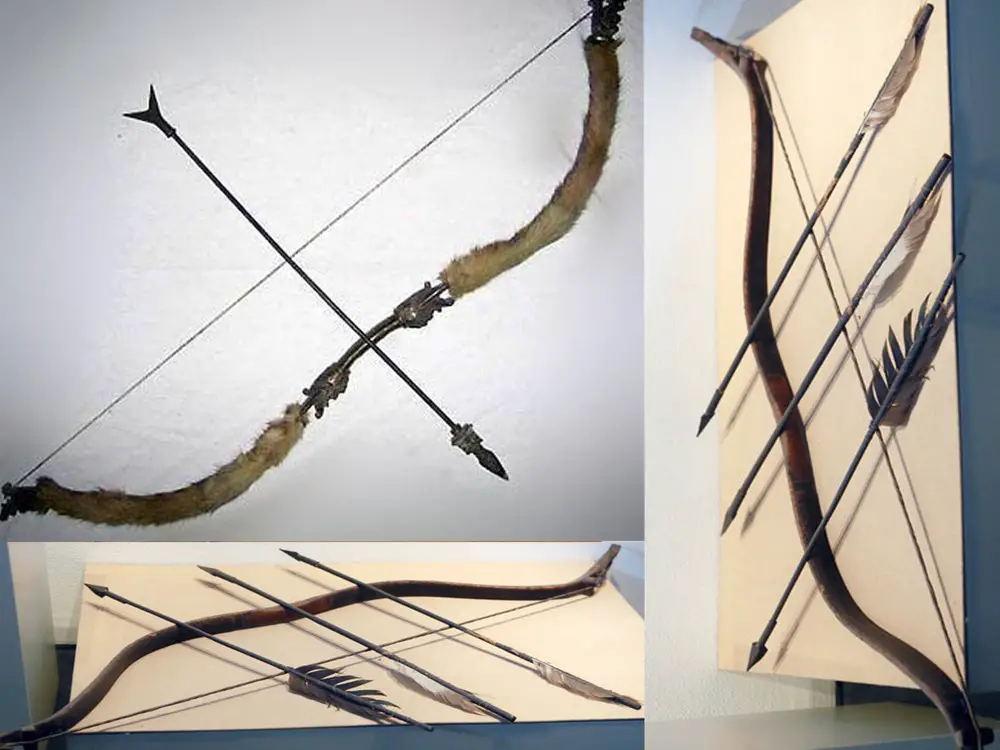

Shang Dynasty bow and arrow

The bows and arrows of the Shang Dynasty were sturdy composite weapons, with a length equivalent to that of an average person’s height. They were crafted from materials such as ox tendons and horn. The arrowheads were made from stone, bone, horn, clamshell, or bronze. The wooden arrow shafts were adorned with feathers and were half the length of the bow. The Shang dagger-axe (ge) featured a bronze blade attached to a 1.1-meter-long wooden shaft. Shields of the Shang Dynasty came in two types: large ones for use on chariots and small ones for infantry. Both types were constructed from wooden frames and leather, with some small shields featuring tiger patterns painted on the surface. Small bronze knives were personal weapons with sheaths. The function of whetstones was similar to the modern “oilstone” used by soldiers.

Qin Dynasty Bow and Arrow

The Qin Dynasty’s bow and arrow possessed considerable power. Qin arrowheads often had inscriptions indicating the maker’s name, supervisor, and quality control, allowing for accountability. The arrow’s design ensured uniformity and facilitated quality control through identification. The bows were powerful, and each arrow had a significant impact on the battlefield.

Han Dynasty Bow and Arrow

Han Dynasty bows and arrows were similar to those of the Qin Dynasty. Records indicate that crossbow deployment was extensive. While less information is available about bows during this period, crossbows played a significant role in Han military forces.

Tang Dynasty Bow and Arrow

The Tang Dynasty had advanced bow-making technology, with improved materials, craftsmanship, and shooting techniques. Archers adopted unique stances and techniques to ensure accuracy. Different bows and shooting methods were chosen based on the situation and target.

Song Dynasty Bow and Arrow

The Song Dynasty emphasized material selection and construction techniques for bows and arrows. The bow’s design featured a composite structure that leveraged elasticity to propel arrows. The arrows were carefully constructed with bamboo shafts and metal arrowheads for balance and precision.

The “Divine Arm Bow” (shén bì gōng), pronounced as [shen bee gong], is a term referring to a type of bow. It is said to have been created by a commoner named Li Hong during the Xining period of the Song Dynasty. The bow is placed on a rack, and it is drawn and fired using foot pedals. It is capable of shooting over a distance of three hundred paces and penetrating heavy armor, hence its name.

Hong Mai, a scholar from the Song Dynasty, mentioned the “Divine Arm Bow” in his work “Rongzhai Sanbi” (Three Records from Rongzhai): “The ‘Divine Arm Bow’ is derived from crossbow techniques, which were not known in ancient times. In the first year of the Xining period (1068), a commoner named Li Hong introduced it to the imperial court… Its construction involves the use of oak wood for the body, sandalwood for the bow arms, iron for the foot pedal tip, copper for the horseshoe-shaped arrow rest, and hemp cord for the bowstring. The bow’s body is three chi and two cun in length, the string is two chi and five cun long, and the arrow, with wooden feathers, is several cun long. It can be shot over a distance of more than 240 paces and can penetrate half an inch into elm wood. Emperor Shenzong personally inspected it and highly praised it. It was subsequently put into use, surpassing other bows and arrows.”

Nalan Xingde, a Qing Dynasty poet, mentioned the “Divine Arm Bow” in his work “Lushuiting Zashi” (Miscellaneous Knowledge from Lushuiting): “The Song Dynasty’s ‘Divine Arm Bow’ is essentially a crossbow. It is called a bow due to its name, but the bowstring is scraped against the crossbow arms to function. The bow’s power is not solely in the arrow; it lies in the arm’s action on the arrow. Shave and lower it, and the string travels through the air, transferring the full force to the arrow.”

This concept is also referenced in Shen Kuo’s “Mengxi Bitan” (Dream Pool Essays): “The Song Dynasty’s ‘Divine Arm Bow’ is originally a crossbow. The term ‘bow’ is used in the name, as the bowstring must scrape against the crossbow arms to work. The power of the bow does not exhaust in the arrow, but in the arm’s action on the arrow. Shave and lower it, and the string will move through the air, transferring the full power to the arrow.”

Ming Dynasty bow and arrow

The Ming Dynasty military primarily employed horn bows, with two standard types of bows: the “Seven Dou Bow” and the “Eight Dou Bow.” The “Seven Dou Bow” required arrows of seven dou weight (a unit of measurement) to achieve a range of about 150 meters, while the “Eight Dou Bow” required arrows of eight dou weight for a range of around 200 meters. The arrows used during Ming Dynasty military training were called “Cu Zi.” These arrows had bamboo shafts, hardwood tails, and iron or copper arrowheads.

Qing Dynasty Bow and Arrow

The Qing Dynasty utilized recurve composite bows made from materials like buffalo horn, wood, and sinew. The large and curved tips of Qing bows allowed for greater draw weight, enabling powerful shots. Fixed grooved string pads dampened vibrations and improved stability.

In summary, China’s long history has seen various types of bows and arrows, each with unique characteristics and contributions to different historical periods.

what does a bow and arrow symbolize?

Symbolism and Significance of Bows and Arrows:

Strength and Capability: The bow requires significant strength to bend, while the arrow demands precise skill to hit the target, symbolizing human strength and capability, conveying courage and prowess.

Accuracy and Target: The accuracy of the arrow hitting its target implies the pursuit of goals, analytical skills, and judgment required in work and life.

Connection and Communication: The perfect pairing of bow and arrow does not occur naturally but requires human creativity and wisdom, symbolizing the connection and communication between individuals.

Resilience and Perseverance: Faced with challenges and difficulties, the adjustment of goals and optimization of strategies symbolize resilience and perseverance.

The Power of Inspiration and Wisdom: The creation and improvement of bows and arrows embody inspiration and wisdom, representing human success in mastering military technology through history and culture. They also represent human innate talents and intelligence.

china bow and arrow wedding

In ancient wedding ceremonies, there were various intricate rituals. One of them involved the bride sitting in a flower sedan chair over a charcoal brazier. However, nowadays, it’s more common for the bride to be helped by a matchmaker and walk directly. Before the bride leaves the sedan chair, the groom must shoot three red arrows towards the sedan door to ward off any potential negative energy that the bride might have encountered along the way. The shooting of the arrows carries symbolic meanings:

First Arrow – To the sky, symbolizing a divine union and a blessing from above.

Second Arrow – To the earth, symbolizing a harmonious and auspicious union on earth.

Third Arrow – To establish the harmony of heaven and earth, representing a long-lasting and eternal bond between the couple.

In ancient wedding customs, after the groom welcomes the bride into the house, he shoots arrows on both sides of the doorway. This tradition originates from the story of the Peach Blossom Female Deity’s confrontation with the Duke of Zhou in the battle of yin and yang. Using a bow made of willow wood and arrows made of peach wood, shooting the left and right sides of the doorway is believed to ward off evil spirits and negative energy, ensuring a peaceful and joyful marriage.

Additionally, there is a traditional superstition to avoid wedding ceremonies on the ox days of the third, sixth, and ninth lunar months, known as “red inauspicious days.” According to folk beliefs, these days accumulate strong negative energy and are considered inauspicious for weddings. It is believed that getting married on these days may lead to a troubled and unstable marriage.

why bow and arrow so important in ancient China?

There are various types of bows and arrows, including longbows, crossbows, and even concealed weapons like sleeve arrows and arrows hidden in the stirrups of a horse saddle. By treading on the bow and releasing, one can cause significant harm to the enemy. Bows and arrows possess great elasticity, allowing them to inflict substantial damage within their effective range. However, it’s important to note that the primary impact comes from the arrow itself, as the bow merely serves as a launching mechanism and does not cause harm on its own.

Arrow shafts are often crafted from bamboo or wood, with feathers attached to the tail. In flight, arrows follow a curved trajectory, and upon impact, the arrowhead pierces first. Arrows are distinct from stones; the latter may not penetrate flesh, whereas arrows, with their arrowheads, can deeply embed into the body. Removing an arrow can cause significant trauma, and the process can lead to profuse bleeding. The effectiveness of arrows in inflicting damage surpasses that of knives and spears, making them advanced weaponry for their time. Arrows can be fired from a distance, allowing for strategic engagement without direct confrontation and preserving one’s own strength.

In ancient times, many hunters carried bows and arrows to wound wild animals, as slingshots were generally only suitable for hunting birds. Arrows could also be coated with poison or narcotics, causing those struck to become poisoned, faint, or even go mad. Additionally, arrows could be disarmed and used to carry messages, shot into enemy strongholds or camps to deliver information. By attaching flammable substances like sulfur and saltpeter, arrows could be transformed into fire arrows, causing fires in enemy supplies, buildings, or stacks of hay, thus undermining the enemy’s morale. Arrows were versatile tools, serving not only combat purposes but also entertainment, as seen in arrow-throwing games like “投壶.”

Emperors and generals placed great importance on archery, especially horseback archery. Skilled archers were rewarded with gifts and recognition, and archery competitions were held during various events. Successful displays of archery on horseback required mastering rhythm, coordinating breathing, and maintaining a sharp eye, judgment, and fundamental archery skills. The integration of horseback mobility and archery contributed to the formidable force of mounted troops on the battlefield.

To inflict harm on the enemy using bows and arrows, strong bows were crucial. As expressed in Du Fu’s “A Song of Frontier: No. 6,” “Draw the bow as strong as possible, use arrows as long as possible. Shoot the rider before shooting the horse, capture the king before capturing the thief.” Strong bows and long arrows could disable horses and subsequently dismount riders or generals, reducing their combat effectiveness. Striking an enemy commander with a single arrow could swiftly conclude battles and earn significant achievements. Archers were highly regarded, and arrows functioned akin to modern missiles – though lacking precise guidance, they could accurately hit targets, especially when launched en masse. It’s fair to liken arrows to a relentless swarm, causing widespread casualties.

Shields were used as defense against arrows, but in many cases, military camps lacked sufficient shields to withstand the onslaught of flying arrows. Shields could provide temporary protection, but they often proved insufficient in preventing casualties in the face of a barrage of arrows.

bow and arrow in Chinese culture

Ancient China’s history of archery traces back to mythical legends and archaeological discoveries. According to legend, archery was initially invented by Shen Nong, and later perfected by Huang Di.

In historical legends, there are many renowned archery heroes, such as Li Guang, the archery hero of the Xia Dynasty, and Hou Yi, the divine archer of the Western Zhou Dynasty. These stories and legends provide us with a preliminary understanding of the origin and development of archery in ancient China.

However, archaeological findings offer a more comprehensive and in-depth insight. The earliest stone arrowhead artifacts were discovered in the late Neolithic period at the Yangshao Culture site, resembling modern arrowheads, confirming that ancient Chinese humans had already begun using arrows for hunting and warfare.

Furthermore, relics related to archery were unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tomb dating back approximately 5000 years. These relics included numerous archery tools such as arrowheads, arrow shafts, and bowstrings.

The development of archery extended beyond weapon improvement; it also reflected the popularization of archery as a sport. In ancient China, archery was widely applied in military, hunting, and traditional folk cultures.

In archery, not only exceptional technical skill was required but also good mental composure and physical fitness.

II. Archery Rituals and Bow Making in Pre-Qin Period: Early Maturation of Ancient Chinese Archery

Ancient Chinese archery culture has a long history, with archery rituals and bow making being essential components during the Pre-Qin period. In the Western Zhou Dynasty, archery rituals were significant ceremonies held in the royal court, demonstrating the authority and military power of the monarchy.

Archery rituals were typically conducted during the spring and autumn seasons, often on palace grounds or nearby squares. Participants included royal family members, nobles, and meritorious officials, while the general populace could only observe.

In archery rituals, rules and methods of archery were crucial. The target was generally a bullseye located around a hundred paces away, requiring archers to hit the target within a specified time frame. Rewards and punishments were also involved; hitting the target resulted in rewards, while missing led to penalties.

During the Spring and Autumn period, the archery philosophies of various schools of thought began to mature. Confucianism emphasized archery as a means of self-cultivation, nurturing virtues and personal qualities.

Daoism regarded archery as a symbol of reverence and worship for heaven and earth. Mohism emphasized the practical and utilitarian value of archery, considering it a skill to maintain social order.

Legalism viewed archery as a necessary military skill to safeguard the nation’s security and stability. The military strategies and tactics of the School of Military Affairs highlighted the importance of archery in combat.

During the Pre-Qin period, bow making also saw significant development and application. Bow making mainly involved two types: longbows made from materials like bamboo, bone, and antler, and short bows made from wood.

Longbows excelled in long-range and power but required higher strength and skill, while short bows were more agile, portable, and easier to use, albeit with shorter range and power. Arrow making consisted of arrow shafts, arrowheads, and feather fletchings.

Arrow shafts were typically made from bamboo or wood, about one meter in length. Arrowheads were crafted from metal such as iron or copper, sometimes bone or stone. Arrow fletchings were feathers attached to the rear of the arrow to stabilize its flight path.

During the Pre-Qin period, bows and arrows played a crucial role as both vital weapons and hunting tools, experiencing widespread application and development. In archery rituals, they showcased martial skills and etiquette while imparting moral and mental strength through archery practice.

Archery was a culture that combined physical training, mental cultivation, and ethical education. Its development was not only reflected in weaponry improvement but also in the cultivation of virtue and discipline.

III. Popularization and Advancement: Evolution of Archery in Qin, Han, and Three Kingdoms Periods

The archery culture of ancient China has a long history, and it underwent a lengthy developmental process. In the periods of Qin, Han, and the Three Kingdoms, archery techniques and theories evolved continuously, and the secularization of archery became increasingly apparent.

Firstly, the diversity of archery techniques was a significant characteristic of the development of archery culture. Not only did traditional bow and arrow techniques persist, but crossbow technology also emerged. Various types of archer units appeared in the military, demonstrating advanced skills and becoming an indispensable force.

During this period, the widespread use of crossbow technology expanded the application of archery techniques.

Secondly, the secularization of archery culture became increasingly evident. Archery-related content appeared in Tang and Song paintings and literature. Painted stone sculptures depicted numerous archery scenes, showcasing people’s enthusiasm and pursuit of archery techniques.

Tang and Song poetry also included references to archery, with themes such as “shooting tigers” and “hunting pheasants.” Additionally, historical records documented activities like “autumn archery,” indicating that archery had permeated various aspects of daily life.

Lastly, the summarization of archery theory and the production of archery equipment were important aspects of archery culture development. During this period, people conducted in-depth research and summarization of archery techniques, producing more sophisticated archery equipment. These advancements not only enhanced accuracy and range but also safeguarded the inheritance and development of archery culture.

IV. Integration and Heritage: Distinctive Development of Archery in the Northern and Southern Dynasties

Archery in ancient China was a significant martial activity, with a long history and diverse development characteristics across different periods. The era of the Northern and Southern Dynasties was a crucial stage for archery development, marked by integration and heritage.

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, large-scale population migration facilitated the integration of archery techniques from north to south. Changes in the economic landscape influenced the development of archery in both northern and southern regions. As populations migrated southward from the central plains, archery culture spread and influenced the southern regions.

The amalgamation of diverse ethnic groups also propelled the development of archery practices. The exchange and fusion of cultures between northern and southern regions promoted the dissemination and integration of archery culture.

Family heritage was another vital factor in archery development. The era’s clan-based social structure reinforced the concept of lineage, providing a foundation for the inheritance of archery skills. The prevailing martial spirit was fueled by political instability, grounding the heritage of archery skills in societal values. Turmoil constrained official education, instilling archery heritage with historical significance.

In addition to men, female archery flourished during the Northern and Southern Dynasties. Female participation in archery became a social trend, giving rise to a group of accomplished female archers.

Women’s archery was not only a significant form of entertainment but was also required for various archery-related activities. This demonstrates the era’s recognition of the importance of archery heritage and acknowledgment of female prowess.

V. Talent Selection and Cultivation: Institutional Development of Archery in the Tang and Song Dynasties

The Tang and Song Dynasties were a golden age for the development of Chinese archery culture. Alongside technical advancements, the institutional framework was well-established. In terms of talent selection, the Tang and Song Dynasties implemented a series of systems to ensure the identification of exceptional archery talents.

Firstly, archery was a key component of the “military examination” (wujv), which selected officials proficient in both literary and military skills. Archery served as a vital test in the military examination, identifying candidates suitable for wartime duties.

Furthermore, archery was a crucial subject within the “military studies” curriculum, allowing students to develop specialized skills.

Secondly, talent cultivation during the Tang and Song Dynasties included a comprehensive archery education system. Archery was a prominent feature of the talent cultivation system, not only as a skill but also as a cultural practice.

Archery served as a means of etiquette education, enhancing physical fitness and moral character. Additionally, archery was a core element of military training and warfare during this period, leading to the widespread promotion of archery skills.

The Tang and Song Dynasties’ archery development showcased a diverse range of features. Archery carried strong leisure elements, with archery activities being a popular pastime during leisure hours.

Female archery experienced unprecedented growth during this era, becoming a social trend that enhanced women’s physical fitness and overall quality of life.

Archery practices diversified during the Tang and Song Dynasties, spanning from grand palace competitions to folk archery among commoners. Archery games underwent refinement and evolution, leading to the emergence of various archery-related pastimes.

Finally, the Tang and Song Dynasties saw the creation of numerous works on archery theory, such as the “Nine-Region Archery Manual” (Jiuyu Jianpu) and “Three Strategies” (Sanlue). These works played a pivotal role in advancing archery techniques.

famous bow and arrow users

Yang Youji (Birth and death years unknown), surname Ying (嬴), clan name Yang, style name Shu (叔), given name Youji (or Yaoji), a military general of the State of Chu during the Spring and Autumn Period. He is a renowned ancient Chinese archer.

Yang Youji can be considered one of the most famous ancient archers. He is associated with many archery-related anecdotes. Yang Youji was likely from Yangguo, and after his state was conquered by the State of Chu, he became a noble of Chu. From a young age, Yang Youji displayed remarkable archery skills, able to catch arrows from all directions and draw a bow weighing a thousand catties with both arms. He was known as a divine archer. In the 16th year of King Gong of Chu’s reign (575 BCE), during the Battle of Yanling between the states of Jin and Chu, General Lü Qi of Jin shot an arrow into the eye of King Gong of Chu. The king summoned Yang Youji and handed him two arrows, instructing him to kill Lü Qi. Yang Youji shot and killed Lü Qi by hitting his neck, causing Lü Qi to fall dead onto his quiver. Yang Youji then reported to King Gong with the remaining arrow, and his name became renowned throughout Chu. “Zhan Guo Ce” records: “In Chu, there was Yang Youji, skilled in archery, able to shoot down willow leaves from a hundred paces away, hitting the target a hundred times with a hundred shots.” The phrases “百发百中” (hundred shots, hundred hits) and “百步穿杨” (pierce a willow leaf from a hundred paces) originate from this account. Yang Youji was known as “养一箭” (Yang One Arrow), as one arrow was enough to secure victory.

Li Guang (died before 119 BCE), Han ethnicity, from Chengji in Longxi (present-day Gansu Province), a prominent general of the Western Han Dynasty.

The Li Guang family had a tradition of archery skills. During a hunting trip, Li Guang mistook a stone in the grass for a tiger, drew his bow, and shot an arrow that embedded the entire arrowhead into the stone. When the Xiongnu invaded Shanggu Commandery, Emperor Jing of Han sent the eunuch attendant Li Guang to resist the Xiongnu. In a battle, Li Guang encountered three Xiongnu warriors, and in the ensuing confrontation, Li Guang’s troops were in a dire situation. Li Guang himself, accompanied by a hundred cavalrymen, pursued the three Xiongnu warriors. He managed to kill two of them and capture one alive. After binding the captive and preparing to return, Li Guang noticed thousands of Xiongnu cavalry approaching. He rode forward with about a dozen cavalrymen and killed the Xiongnu general Bai Ma. In the ninth year of Emperor Wu of Han’s Yuanshuo era, Li Guang led four thousand cavalrymen from Right Beiping and was surrounded by forty thousand Xiongnu cavalry led by King Xiān of the Xiongnu. Li Guang’s soldiers were terrified, but he sent his son Li Gan on a fast horse to charge at the enemy. Li Gan and a few cavalrymen rode out, circled around the Xiongnu formation, and returned, reporting to Li Guang that “the Xiongnu are easy to deal with.” His soldiers then calmed down. Li Guang personally used a large yellow crossbow to shoot at the Xiongnu deputy general, killing several leaders.

Lü Bu (died February 7, 199), style name Fengxian (奉先), born in Jiuyuan County, Wuyuan County, Longxi Commandery (present-day Inner Mongolia Jiuyuan), a notable general in the late Eastern Han Dynasty.

Lü Bu is most famous for his feat of shooting a halberd at a gate. This is not a fictional account from historical novels but a documented event. In the first year of Jiān’ān (196), warlord Yuan Shu dispatched General Ji Ling with over thirty thousand troops to attack Liu Bei. Seeking help, Liu Bei requested aid from Lü Bu. Lü Bu led a thousand infantry and two hundred cavalry to swiftly march to Xiaopei. He established a camp about one mile southwest of Xiaopei and invited Ji Ling and others to a banquet. Lü Bu said to Ji Ling and his companions, “Xuande (Liu Bei) is my virtuous younger brother. He is currently surrounded by all of you. I have come specifically to save him. I, Lü Bu, dislike seeing people quarreling with each other. I only enjoy settling disputes for others.” Lü Bu then ordered a halberd to be set up at the camp gate and said, “Gentlemen, watch me shoot the small blade on the halberd. If I hit it with one arrow, you should immediately stop the attack and leave. If I miss, you can stay and fight Liu Bei to the death.” Lü Bu drew his bow and shot an arrow that precisely struck the small blade on the halberd. The commanders were amazed and praised, “General, your power is truly like that of a god!” The following day, Lü Bu held a banquet with the commanders, and they then each returned to their own troops.

Taishi Ci (166–206), style name Ziyi (子义), from East Lai, Huang County (present-day Longkou, Shandong), a famous general in the late Eastern Han Dynasty.

Taishi Ci was exceptionally tall at seven chi and seven cun, had a handsome beard, and was an adept archer with a remarkable ability to shoot without missing. His archery skills were indeed renowned. While accompanying Sun Ce to suppress Ma Bao’s bandits, one of the bandits insulted Sun Ce’s army from a watchtower and held onto a pillar. Taishi Ci used a bow and arrow to shoot him, piercing through the bandit’s wrist and nailing him to the pillar, astonishing everyone present.

Xiao Ruqing (515–572), style name Mingyue (明月), from Tai’an Di (present-day Shouyang County, Shanxi), a notable military strategist and general from the Northern Wei to the Northern Qi Dynasties.

Since a young age, Xiao Ruqing excelled in horseback riding and archery, becoming renowned for his martial skills. In the late Northern Wei period, Xiao Ruqing accompanied his father, Helu Jin, on a western campaign. When the prime minister’s chief clerk, Mo Xiaohui, saw this, Xiao Ruqing shot an arrow while riding at full speed and captured him. Xiao Ruqing was only seventeen years old at the time. He received recognition from Emperor Gao Huan of the Northern Qi and was promoted to the rank of commandant. During a hunting trip at Huan Bridge with Gao Cheng, they spotted a large bird soaring with its wings spread. Xiao Ruqing used a bow to shoot the bird, hitting it squarely and causing it to fall. The bird resembled a spinning wheel as it tumbled down, turning out to be a large eagle. Gao Cheng praised him and exclaimed, “A true eagle-shooting hand!” He became known as “落雕都督” (The Commander Who Shoots Eagles). He was later appointed as Left Guard General and enfeoffed as a count.

Changsun Sheng (551–609), style name Jisheng (季晟), also known by his nickname “Elder Goose,” from Longmen County, Jingzhao Commandery (present-day Xiu Village, Hejin City, Shanxi), a prominent general, military strategist, and diplomat of the Sui Dynasty.

Changsun Sheng was skilled in horseback riding and archery, surpassing his peers. During the early years of the Sui Dynasty, the Tujue Qaghan who had been friendly to the Sui turned hostile. Emperor Yang dispatched General-in-Chief of the Right Flank Zheng Rentai as the main commander and Changsun Sheng as the deputy commander to lead an army against the Tiele tribes in the Tian Shan Mountains. Before departing, Emperor Yang held a banquet and challenged Changsun Sheng to shoot five layers of armor. Changsun Sheng successfully shot through five layers of armor with a single arrow, astonishing the emperor, who rewarded him with strong armor. Afterward, Changsun Sheng and Zheng Rentai led their forces to the Tian Shan Mountains, where they defeated the Tiele tribes in a decisive battle. Changsun Sheng personally killed three Tiele leaders in battle, earning his reputation.

Shi Wansui (549–600), style name unknown, from Duling County in Jingzhao Commandery (present-day Xi’an City, Shaanxi), a distinguished general of the Sui Dynasty.

Shi Wansui hailed from the Western Regions, skilled in equestrianism, and a keen reader of military texts. In the second year of Da Xiang (580) of the Northern Zhou Dynasty, Emperor Jing of Northern Zhou was young, and the paramount chancellor Yang Jian held power. The general of Xiangzhou, Weichi Jiong, openly rebelled against Yang Jian. Shi Wansui accompanied the General of the Expeditionary Army, Liang Shuyan, to suppress the rebellion. When the army arrived at Fengyi Commandery (present-day Dali County, Shaanxi), a flock of geese flew by. Shi Wansui said to Liang Shuyan, “Please allow me to shoot the third goose from that row.” He took his bow, shot the arrow, and struck the third goose, which fell in response to the string’s twang. Seeing Shi Wansui’s exceptional archery skill, the entire army was impressed and admired him. After the establishment of the Sui Dynasty, in the third year of Emperor Wen of Sui’s reign, Shi Wansui, as a general, participated in the campaign against Chen and played a significant role in restoring order in the south. He was known for leading from the front, caring for his subordinates, and achieving multiple victories in both southern and northern campaigns.

Xue Rengui (614–March 24, 683), with the given name Li and the courtesy name Rengui, was a renowned military general in the early Tang Dynasty. He hailed from Xiucun, Longmen County, Jingzhao Commandery, Hedong Circuit (present-day Xiucun, Hejin City, Shanxi Province).

In the first year of the Longshuo era (661), the Khagan of the Western Turkic Khaganate, who had maintained friendly relations with the Tang Dynasty, passed away, and his successor, Bisu, turned hostile towards the Tang. Emperor Gaozong appointed Zheng Rentai as the commanding general of the Right Tuntian Guards, with Xue Rengui as his deputy, and ordered them to lead troops to the Tianshan Mountains to confront the Nine Clans of the Tiele Confederation.

Before their departure, Emperor Gaozong hosted a banquet in the palace and challenged Xue Rengui, saying, “In ancient times, there were skilled archers who could shoot through seven layers of armor. Try shooting through five layers.” Xue Rengui accepted the challenge, donned the armor, took up his bow and arrow, and released the shot. The twang of the bowstring echoed, and the arrow pierced through five layers of armor. Emperor Gaozong was greatly astonished and immediately rewarded Xue Rengui with strong armor.

With Zheng Rentai and Xue Rengui leading the troops to the Tianshan Mountains, the Nine Clans of the Tiele Confederation resisted with a force of over a hundred thousand, and they sent dozens of brave knights to challenge the Tang forces. Xue Rengui, on the frontlines, shot three arrows and killed three challengers. The remaining knights were awed by Xue Rengui’s might and dismounted to surrender. Exploiting the advantage, Xue Rengui launched a full-scale attack, decisively defeating the Nine Clans of the Tiele Confederation and slaying those who had surrendered. Subsequently, Xue Rengui crossed the northern desert and pursued the defeated Tiele forces, capturing three brothers, including Ye Hu (the leader). From then on, the power of the Nine Clans of the Tiele Confederation waned, and they no longer posed a threat to the border. This event is known as the “Three Arrows Conquer the Tianshan.”

bow and arrow in Chinese mythology

Long Tongue Bow

The Long Tongue Bow was a type of bow and arrow crafted by the Shu Han general Zhuge Liang during the Three Kingdoms period. Made with dragon tendons as the bowstring, it gained fame for its exceptional craftsmanship, long range, and high speed. It was recognized as one of the top ten famous bows of the Three Kingdoms. The crafting process of the Long Tongue Bow involved hollowing out a piece of animal horn to create a string hole. A sturdy piece of ox horn was used for the bow, and the string hole was meticulously polished. The tendons were roasted to soften them. The ox horn was bent against the bow slightly, forming the grip, with one end inserted into the string hole and the other end left as a string loop. The tendons were wrapped around the bow’s limb once, threaded through the string hole, wrapped around the string loop, and then tied at both ends using wooden pieces. The bow was finally assembled using glue and left to dry before use. Legendary accounts from the Three Kingdoms era depict the Shu Han general Lü Bu using the Long Tongue Bow to shoot down a spear at a gate in the novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms.”

Myriad Stone Bow

The Myriad Stone Bow was a powerful type of bow and arrow made from the exceptionally hard but lightweight purple sandalwood. It was capable of launching heavier arrows at greater distances than conventional bows. Huang Zhong, a Shu Han general during the Three Kingdoms period, was known to have used the Myriad Stone Bow. The arrows shot from this bow weighed an astonishing seven “dan,” which is equivalent to 700 grams, more than twice the weight of regular arrows. The crafting of the Myriad Stone Bow was highly intricate, involving the selection of the finest wood and materials, and it underwent multiple stages of production. The power of the Myriad Stone Bow was also influenced by the bowstring. Generally, a thicker and more resilient bowstring allowed for the launch of heavier arrows and greater force. Due to the bow’s lighter weight, careful attention was required to maintain a proper grip during use to prevent slipping and loss of control.

Wandering Son Bow

The Wandering Son Bow is one of the ten famous bows from ancient China, known for its exceptional craftsmanship and potent killing power. Characterized by its long bow body, the Wandering Son Bow allowed for easier pulling and faster arrow speeds, resulting in greater range. Crafting the Wandering Son Bow was a labor-intensive process that involved selecting the highest quality wood and materials and undergoing multiple production stages. The bowstring material was of utmost importance and had to be strong and resilient, using materials such as silk, hemp, or bamboo to ensure the bow’s effectiveness. The Wandering Son Bow possessed immense power, easily capable of penetrating heavy armor and delivering lethal blows to enemies. In ancient warfare, the Wandering Son Bow became a reliable ally for many generals and a favorite among archers. Beyond warfare, the bow was widely used for hunting and target practice. In modern archery sports, the Wandering Son Bow continues to be a popular choice among archery enthusiasts.

Divine Arm Bow

Also known as the Divine Arm Crossbow, the Divine Arm Bow was invented during the Northern Song Dynasty under Emperor Shen Zong’s reign. The bow had a length of three chi and three cun (approximately 110 cm) and a string length of two chi and five cun (approximately 85 cm), allowing for a range of over 240 steps (approximately 180 meters). The crossbow had three levels of draw strength, which are roughly equivalent to 53.1 kg, 70.8 kg, and 88.5 kg in modern terms.

Spirit Treasure Bow

According to available records, the Spirit Treasure Bow is one of the renowned ancient bows. It shares a subtle connection with England’s “Spirit Treasure” arrows. Its origin and legend are associated with Li Guang, the Flying General of the Western Han Dynasty. Legend has it that this bow was lightweight, yet when fully drawn, its feathered arrows could shatter stones within a hundred paces. In the game “The Fate of Heaven and Earth: The Return of the City,” the Spirit Treasure Bow possesses unique capabilities, granting the wind character consecutive attacks and enhancing damage for dark attribute spirits.

Skyquake Bow

The Skyquake Bow was the weapon of choice for Tang Dynasty general Xue Rengui. It played a significant role when Xue Rengui led his troops to engage the Tujue people in battle near the Tianshan Mountains. The Tujue were skilled equestrians and renowned for their archery, but Xue Rengui utilized the power of the Skyquake Bow to subdue them. The bow was crafted from exceptional materials and possessed extraordinary strength and range, enabling Xue Rengui’s victory over the Tujue forces.

Overlord Bow

In the novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” the Overlord Bow is associated with Zhao Yun, a general from the Shu Han faction during the Three Kingdoms period. The Overlord Bow, made from black sandalwood and white bronze, featured bowstrings spun from flax fibers. The arrows used with this bow were composed of three parts: iron core, silver shaft, and jingling bells at the head. The bowstring produced a distinctive sound upon release and was capable of causing severe injury. The Overlord Bow’s unique design made it difficult for opponents to evade its effects.

Shoot-the-Eagle Curved Bow

The Shoot-the-Eagle Curved Bow is the weapon of Guo Jing, a character in Jin Yong’s wuxia novel “The Legend of the Condor Heroes.” The novel describes the scene where Guo Jing showcases his archery skill using the Shoot-the-Eagle Curved Bow: “Han Baoju tugged at the reins, and his chestnut horse surged forward before suddenly coming to a halt. No matter how much he urged it, the horse remained still. Han Baoju realized something was amiss and looked ahead, where a group of people had gathered. Several leopards were clawing and scratching the ground. Han Baoju knew his steed was afraid of leopards, so he dismounted, holding the Golden Dragon Whip in his hand.”

Xuan Yuan Bow

The Xuan Yuan Bow, also known as the Xuan Yuan Qian Kun Bow, was one of the ten famous ancient bows. It was associated with the divine artifact “Xuan Yuan Qian Kun Arrow” and held connections to the legendary figure Emperor Xuanyuan, an ancient ruler. The bow was crafted from materials including Southern Wu haozhe (a type of wood), Yanchong (ox horn), and Jingmi (deer tendon). Emperor Xuanyuan, also known as the Yellow Emperor, was said to have created this bow, which had the power to pierce through hearts with three arrows, symbolizing its remarkable strength and effectiveness.

Shoot-the-Sun Bow

The Shoot-the-Sun Bow, also known as Hou Yi’s Bow, is one of the ten great divine artifacts of ancient times, mentioned in the mythology of ancient China. Hou Yi was a legendary archer who was known for shooting down nine of ten suns that were scorching the earth. In Chinese mythology, the Shoot-the-Sun Bow was described as red in color, while the arrows were white and had a crescent shape. Hou Yi was a student of the fire god Zhu Rong and became a master of archery, ultimately using the Shoot-the-Sun Bow to save the world. The bow played a crucial role in myths and legends as a symbol of heroism and divine power.

Chinese bows and arrows story

Guan Zhong Shooting Duke Huan of Qi’s Belt Hook

Guan Zhong once shot an arrow that struck the belt hook of Duke Huan of Qi, rather than hitting Duke Huan himself. This event occurred during the power struggle between Duke Huan’s sons, Duke Xiao Bai and Duke Jiu, over the throne of Qi. Guan Zhong supported Duke Jiu’s faction. In an attempt to eliminate Duke Xiao Bai, Guan Zhong sneaked into the enemy’s camp and shot an arrow towards Duke Xiao Bai’s abdomen. However, he only managed to hit Duke Xiao Bai’s belt hook, which was often made of jade and served as a clasp for clothing. This prevented the arrow from hitting its target. Eventually, this incident led to Duke Xiao Bai’s successful ascension to become Duke Huan of Qi.

This event showcases the cunning of Duke Xiao Bai and the precise archery skills of Guan Zhong.

Li Guang Shooting Shi Hu

This story narrates how Li Guang mistook a large stone in a thicket for a tiger and shot an arrow at it. The arrowhead got embedded in the stone. Li Guang repeatedly shot arrows at the stone, but he couldn’t make the arrow penetrate it again. Li Guang had previously encountered tigers in the region he lived before and had personally killed one. While residing in the region of Right Beiping, Li Guang also encountered a tiger. During this encounter, the tiger leaped at him, injuring him. Li Guang eventually managed to shoot and kill the tiger.

Three Arrows Conquering the Tian Shan

The phrase “Three Arrows Conquering the Tian Shan” originates from the biography of Xue Rengui in the “New Book of Tang.” Xue Rengui was ordered to establish defenses in Yunzhou. Upon arrival, he was challenged by three knights from Bohai, an enemy state. Xue Rengui used three arrows to defeat all three opponents, instilling fear in the enemy forces and relieving the need for further defense. When Xue Rengui returned to Chang’an, he was warmly welcomed by the emperor, officials, and the people.

This phrase has come to symbolize a great general’s extraordinary martial prowess and awe-inspiring reputation.

Xiongnu Arrows with a Whistle

Xiongnu arrows with a whistle were a type of arrow used by the Xiongnu, an ancient nomadic people of the Eurasian Steppe. In the account of Emperor Wu of Han’s journey to Kuaiji, these arrows are mentioned. The leader of the Xiongnu, Modu Chanyu, invented these whistling arrows to ensure the obedience of his soldiers. He commanded that any target hit by these arrows must also be struck by the soldiers. Modu Chanyu tested the effectiveness of these arrows by shooting his beloved horse and concubine, and his soldiers followed suit. This innovation underscored his authority and control over his forces.

These whistling arrows were a form of military command and had symbolic significance in ancient times.

Chinese bows and arrows in feng shui

In traditional Chinese culture, the bow and arrow symbolize courage and strength. They were indispensable weapons during ancient times of warfare and were revered as elite weaponry on the battlefield. Archers were highly respected figures among ancient military leaders, embodying the concept of “courage under a single arrow.” The bow and arrow not only represent physical power and bravery but also hold significant spiritual and cultural symbolism.

Feng Shui Significance of the Bow and Arrow

In ancient times, the bow and arrow were not only weapons but also widely utilized in Feng Shui practices. This is because the courage and strength represented by the bow and arrow were believed to bring better fortune and positive energy to specific locations. The Feng Shui significance of the bow and arrow includes several aspects:

Dispelling Negative Energy: In ancient times, the bow and arrow were often employed to counteract evil and supernatural entities. Therefore, they also have a role in dispelling negative energies in Feng Shui. When there is unfavorable energy or ominous qi present in a home or workspace, the bow and arrow can be used to disperse such energies.