Traditional Chinese architecture is a unique and intricate style of construction that has a rich history and cultural significance. The architecture of China has evolved over thousands of years, blending the influences of different dynasties, regions, and religions to create a distinctive aesthetic. From the grandeur of the Forbidden City to the tranquil beauty of a traditional courtyard, Chinese architecture embodies the country’s history, culture, and philosophy.

One of the most notable features of traditional Chinese architecture is the emphasis on symmetry and balance. This is evident in the layout of buildings, the arrangement of courtyards, and the use of decorative elements such as lanterns, carvings, and paintings. Chinese architecture is also known for its use of natural materials, such as wood, stone, and clay, which are often intricately carved or painted to create intricate designs and patterns.

what are Chinese architecture buildings?

Traditional Chinese architecture refers to the architecture before the mid-19th century, from the pre-Qin period to before the 19th century. It is an independently developed architectural system. The formation of the traditional Chinese architectural style has undergone a long historical process, and is one of the characteristic cultures gradually formed by the Chinese nation through practice over thousands of years, as well as the accumulation of the laboring people’s creation and wisdom in various periods of China.

Traditional Chinese architecture is the most brilliant and intuitive carrier and manifestation of China’s long-standing traditional culture and national characteristics. The grandeur is reflected in the large doors, windows, deep entryways, and wide eaves, giving people a sense of relaxation. The semi-enclosed space formed under the large eaves provides both shelter from the sun and rain and an open view that leads directly to nature. There are many types of ancient Chinese architecture, mainly including palaces, temples, monasteries, pagodas, residential buildings, and garden architecture.

what are the main characteristics of Chinese architecture?

The main characteristics of Chinese architecture include the following:

Framework structure

This is an important feature of ancient Chinese architecture. Most ancient Chinese buildings were constructed using a wooden frame structure, with the weight of the roof and eaves transferred to the pillars through the beam frame. The components were primarily connected by mortise and tenon joints without using nails or other auxiliary tools. The walls were only used as partitions, rather than structural components supporting the weight of the building. The proverb “when the walls collapse, the building remains standing” broadly indicates this important feature of Chinese architectural framework structure.

Individual buildings

Ancient Chinese buildings typically consist of several individual buildings, which can be roughly divided into three parts: terrace foundation, main body, and roof terrace pedestal. The foundation is constructed of bricks or stones and supports the entire house. The main body is supported by wooden pillars and divided by doors and windows. Above the main body is the roof, which is made of a wooden frame and extends outward to form a soft and elegant curved shape, covered by blue-gray bricks or glazed tiles.

Diverse colors

In ancient Chinese architecture, decoration and ornamentation were especially important, and all building components were intended to be beautiful. Mineral materials such as green, yellow, and red were often used to form colorful patterns, enhancing the beauty of the building. The decoration colors were also different due to the different properties of the selected components. Bridges, pedestals, and steps were often carved and decorated with railings, making the buildings appear particularly grand and magnificent.

Symmetrical layout

Ancient Chinese architecture generally followed the principles of introversion, implicitness, and multilevel, striving for balance and symmetry. It mainly adopted group combinations and layouts with overall symmetry along the central axis. Each building group had at least one courtyard, with several or dozens of courtyards of different levels to compensate for the limitations of individual buildings. In addition, the floor plan was generally unfolded along the central axis and took the form of left-right symmetry, with the center being the courtyard and the surrounding buildings.

what are Chinese buildings made of?

Chinese ancient architecture belongs to the form of wooden structure, and the main material is still wood, followed by auxiliary materials such as bricks, tiles, and stones.

Chinese ancient architecture can be classified into the most common wooden structure, stone-wood structure (such as Tibetan ancient architecture like Potala Palace), stone structure (such as stone archways, stone bridges, and parts of the Great Wall in some areas), earth structure (such as the Great Wall in the Qin and Han dynasties, and cave dwellings in the northern Shaanxi region), brick structure (such as screen walls, enclosures, etc.), and bamboo architecture (bamboo buildings in minority areas in the southern part of China).

In summary, according to the structural characteristics of different buildings, the main building materials used in ancient Chinese architecture are: wood, bricks and tiles, stones, earth, bamboo, etc., and other materials include: white lime, blue-grey bricks, yellow clay, aga soil, border grass, hemp, brick powder, paint, blood pigment, tung oil, gold, colored glaze, copper, balin green, and various pigments.

What materials were used to build ancient Chinese architecture? There are mainly four types:

Firstly, roofing materials.

The ancient Chinese commonly used glazed tiles and clay tiles as roofing materials. Glazed tiles are splendid and reflect beautiful light under the sunshine. They were often used in palace architecture, such as the Forbidden City.

Ceramic tiles are a relatively common building material with high strength and wide usage. They can be seen in ancient Suzhou gardens and buildings in southern China. These are the two most widely used roofing materials.

Secondly, frame materials.

The ancient Chinese commonly used wood as frame materials. There are various reasons why the Chinese use wood. The main reason is that Chinese architecture mostly emphasizes fast and practical construction, so wood structures are used more often.

Lián Qǐchāo believed that the Chinese thought that houses could not exist for thousands of years, so the Chinese chose the most convenient materials for building.

Thirdly, wall materials.

The wall materials of ancient Chinese architecture generally used waterproof mortar and oiled paper, which are highly waterproof.

In royal palace wall architecture, some pigments were painted on the walls, usually in scarlet and purple. This is because scarlet and purple are symbols of imperial power and give a sense of majesty.

Meanwhile, ordinary households have white or gray walls and are not allowed to dye them red or purple, to not overstep the authority of the monarch!

Fourthly, door and window materials.

The doors and windows of ancient Chinese architecture are generally made of wood, with golden nanmu and redwood being the main materials. These two kinds of wood have good texture and are not easily corroded, so they are widely used.

Golden nanmu is the king of wood, with a high price and low yield. According to reliable historical records, the yield of golden nanmu often could not meet the needs of royal architecture, which shows its preciousness.

In addition to golden nanmu, redwood is also the preferred material for ancient architecture. It is sturdy, has a good color, is moderately priced, and has a high yield, so it is used the most.

why do Chinese buildings have holes in them?

- Ventilation bricks are used to solve the ventilation problem of wooden pillars in brick walls. Sometimes, they are made into hollow patterns for aesthetic purposes.

- Dongmen, also known as door openings, are a special type of door in ancient Chinese architecture that combines decoration with practicality. Dongmen is widely used in classical gardens, usually opening caves on walls, corridors, pavilions, and other buildings, without doors or gates, for people to pass through.

Dongmen has various forms, and it complements the scenery in the garden, making it an indispensable decorative element. Dongmen comes in many forms, including circular, horizontal, vertical, guishi, elongated hexagonal, regular octagonal, elongated octagonal, dingsheng, haitang, peach, gourd, autumn leaves, and Han vases, and each type has many variations. For example, the upper edge of rectangular Dongmen, in addition to being a horizontal line, can also have a raised center or be connected by three or five arcs. The upper corners of Dongmen can have simple haitang patterns, or complex ones with added corner flowers resembling sparrows, or they can be designed with various patterns such as swirls and clouds.

what are Chinese buildings aligned on an exact north/south axis?

Chinese buildings that are aligned on an exact north/south axis are called “north-south oriented buildings” or “zhengjian buildings” in Chinese. This architectural tradition dates back to ancient times and is still commonly used today. The north-south orientation is believed to be auspicious in Chinese culture, as it symbolizes the alignment of the building with the natural world and the flow of energy, or qi. This alignment is also important in feng shui, the Chinese practice of creating harmonious environments by optimizing the flow of energy.

In Chinese architecture, it was common for significant buildings and royal palaces to be arranged on a precise north-south axis, with the primary entrance facing south. Even if a building consisted of multiple sections connected by courtyards, each section would also be aligned along the same north-south axis, creating a cohesive and harmonious overall design.

what is Chinese architecture called?

Chinese architecture is simply called “中國建築” (Zhōngguó jiànzhù) in Chinese, which literally means “Chinese architecture.”

history of Chinese architecture building

In the Paleolithic Age 500,000 years ago, our ancestors in China utilized natural caves as their dwellings. During the Neolithic Age, tribes in the middle reaches of the Yellow River used rammed earth for walls and built semi-underground houses with wooden frames and grass and mud. In the Yangtze River basin, post-and-beam structures emerged.

During the pre-Qin period, many cities were built on the land of China, and rammed earth technology was widely used in building walls and platforms. The Western Zhou Dynasty constructed Gaojing and Luoyang.

During the 500 years of the Qin and Han Dynasties, Chinese architecture reached a pinnacle of development. Qin Shihuang employed the entire country’s labor and resources to build a capital city, palaces, and mausoleums in Xianyang. Liu Bang established the Han Dynasty and built the Changle Palace. Emperor Wu of Han Dynasty built the Great Wall on a large scale five times.

The Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties was a period of great national integration in Chinese history, during which traditional architecture continued to develop, and foreign Buddhist architecture was introduced. The Northern Dynasty built the capital city of Luoyang, and the Southern Dynasty built the city of Jiankang. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, Buddhism greatly developed, and the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang were excavated.

During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, architecture inherited the achievements of the previous dynasties and was also influenced by foreign cultures, forming an independent and complete architectural system, pushing Chinese architecture into a mature stage. The Sui Dynasty excavated the Grand Canal, and the famous craftsman Li Chun built the Zhaozhou Bridge. The Tang Dynasty built huge palaces, imperial gardens, and official offices. Temples and pagodas also appeared in large numbers, such as the Buddha’s Light Temple on Wutaishan Mountain and the Big Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi’an.

Since the Northern Song Dynasty, architecture has developed towards refinement and delicacy, and decoration has become particularly exquisite. The Yuan Dynasty built the capital city of Dadu, and the Ming Dynasty constructed the two capitals of Nanjing and Beijing. In terms of architectural layout, it was more mature than the Song Dynasty. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the emperors built imperial gardens and private gardens, creating a peak in garden architecture in Chinese history.

In modern and contemporary Chinese architecture, traditional architectural styles are inherited while Western architectural technology is absorbed, resulting in a large number of unique buildings, such as the Kaiping Diaolou. Since the reform and opening up, Chinese architecture has blossomed, with the construction of public housing at the foot of the Great Wall, the Bird’s Nest stadium, the Xiangshan Campus, and the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, among others.

who invented Chinese architecture?

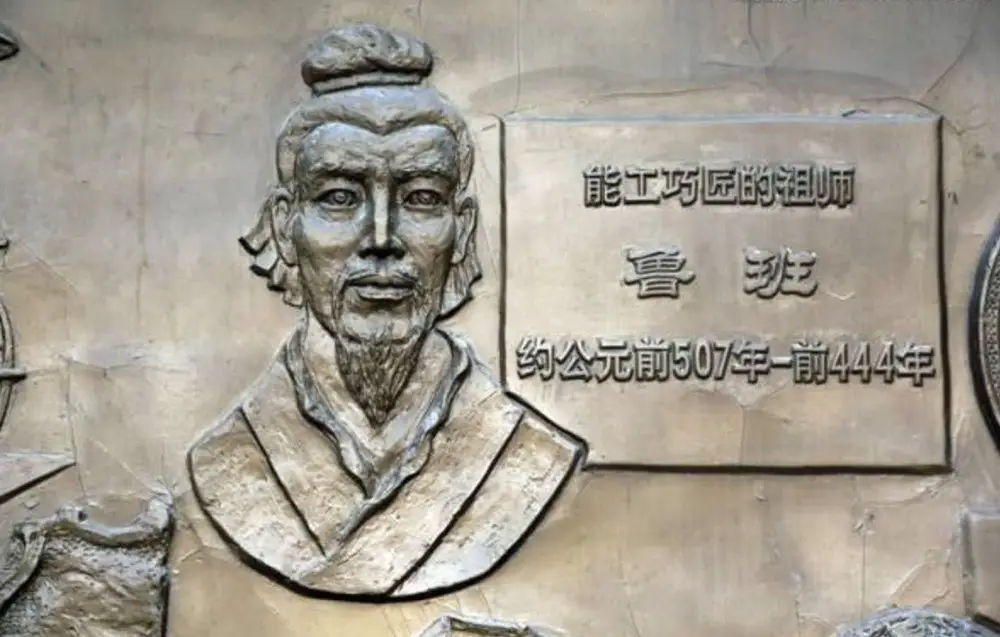

Lu Ban (507 BC – 444 BC) was a person from the State of Lu during the Spring and Autumn period in ancient China. He was of the Ji family, and his given name was Ban. He was also known as Gongshu Pan, Gongshu Ban, Banshu, and was often referred to as “Master Lu Ban”. He is considered a symbol of the wisdom of ancient working people.

For over 2400 years, the collective creations and inventions of ancient working people have been attributed to Lu Ban. Therefore, stories about his inventions and creations are actually stories about the invention and creation of ancient working people in China. The name Lu Ban has become a symbol of the wisdom of ancient working people.

Lu Ban was a skilled craftsman and was highly respected for his craftsmanship. Born into a family of generations of craftsmen, Lu Ban was exposed to knowledge about construction and woodworking from a young age. He not only had a good understanding of building structures, but also had strong practical skills. He invented many ingenious techniques, so what did Lu Ban invent?

During the Spring and Autumn period, many crafts were being invented, and the environment was very open to skills at the time, so Lu Ban had many opportunities. There were many inventions credited to Lu Ban. Everyday items such as umbrellas, saws, rulers, and ink pots, as well as some inventions related to agriculture and sculpture, were created by him. This shows that Lu Ban was a person who loved to invent and create. As a craftsman who loved to create, the initial designs of these things were all for the convenience of people. The invention of the umbrella, for example, was because Lu Ban saw his wife working in the scorching sun and designed a movable pavilion with a shade, which led to the initial form of the umbrella.

Not only did he create small-scale inventions, but he also created weapons, such as the cloud ladder, which was specifically used to attack cities. With it, soldiers could stand high and see the entire city, which was very useful for controlling the terrain during battles. In addition to weapons, there were also agricultural tools. Although modern people admire high technology, there are still some tools that are used by people, such as the stone mill. In the past, people used a pounding method for work, but the invention of the stone mill changed vertical movement to rotary movement, which saved a lot of effort.

No matter what Lu Ban invented, his ultimate goal was to benefit the people.

famous Chinese architects

Masters of ancient Chinese architecture:

- You Chao Shi – China’s first master builder and his “primitive house”

- Ji Dan and Mi Mou – China’s first pair of urban planners and builders

- Lu Ban – the representative of Chinese folk craftsmen (architects)

- Ying Zheng and Meng Tian – creators of centralized state architectural culture in China

- Xiao He, Yang Cheng Yan, Liu Che – pioneers of Western Han architectural style

- Cao Cao, Tuoba Hong, Mu Liang, Li Chong – planners and builders of the Cao Wei Ye City and the Northern Wei Luoyang City

- Qimu Huaiwen, Guo Anxing – pioneers of Chinese stupa construction technology

- Liu Ling, Tao Yuanming – the influence of Wei Jin literati on architecture

- Yu Wen Kai – the architect of China’s first “Renaissance”

- Yan Lide, Liang Xiaoren – the rise and fall of the Tang Dynasty’s “bold and strong” architectural style

- Wang Wei, Bai Juyi – the architectural achievements of Tang Dynasty literati and folk craftsmen

- Zhang Zeduan – “Qingming Shanghe Tu” and the Song Dynasty’s Bianjing (Kaifeng)

- Wang Yucheng, Su Shi, Su Shunqin – Song Dynasty literati architects and folk craftsmen

- Yu Hao, Li Jie – two outstanding architectural theorists of the Song Dynasty

- Famous buildings of anonymous craftsmen from the Liao Dynasty

- Zhu Xi, Zhang Hao, He Chengzhen – creators of the new “Three Kingdoms” (Southern Song, Jin, Western Xia) architecture

- Liu Bingzhong, Guo Shoujing, Yemodi’er – planners and architects of the ecological city Yuan Dadu in the Yuan Dynasty

- Anige, Zhang Liusun, Alao Ding – creators of “cross-cultural” architecture in the Yuan Dynasty

- Zhu Di, Kuai Xiang, Wu Zhong, Ruan An – builders of the Ming capital and palace

- Sanluo Lama, Bandan Zangbu, Guo Jin – Ming Dynasty “Imperial Decree” religious architecture

- Lu Rong, Ji Cheng, Zhang Lian – designers of Ming Dynasty private homes and gardens

- Liang Jiu, Lei Fada (Style Thunder) – professional architects serving the Qing court

- Li Yu, Ge Yuliang, Yao Chengzu, Li Juchuan – folk architects and gardeners in the Qing Dynasty

- Founding father of carpentry: Lu Ban; overseer of the construction of the Sui Dynasty’s new capital, Daxing City: Yu Wen Kai;

- Builder of the Zhaozhou Bridge in the Sui Dynasty: Li Chun; Master builder Li Jie authored “Yingzao Fashi,” a treatise on architectural methods

- Reconstruction of the Forbidden City: In 1695, during the 34th year of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign, Liang Jiu oversaw the reconstruction of the main halls inside the Forbidden City.

types of Chinese architecture

Royal Buildings: The Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace, the Chengde Mountain Resort, and the Shenyang Imperial Palace.

Imperial Tombs: The Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang and the Terracotta Warriors, the Ming and Qing Imperial Tombs.

Religious Buildings: The Zhongshan Ancient Building Complex, the Wudang Mountain Ancient Building Complex, the Wutaishan Ancient Building Complex, and the Potala Palace.

Defensive Structures: The Great Wall, the Tulou Buildings in the Tibetan and Qiang Ethnic Regions.

Residential Buildings: The Huizhou and Southern Anhui Ink-Wash Residential Buildings, the Jiangnan Water Town Residential Buildings, the Shanxi Wang Family Compound, the Qiao Family Compound, the Unique Circular Residential Buildings, and the Overseas Chinese Culture Represented by the Sino-Western Fusion in Rural Areas.

Ancient Chinese architecture has a long history and magnificent achievements, and it is also an important object of artistic appreciation.

style of ancient Chinese buildings

Hall

The hall is the main building in the ancient Chinese architectural complex, including two types of buildings: the hall and the palace, with the hall being used for palaces, rituals, and religious buildings. The terms “hall” and “palace” first appeared in the Zhou dynasty. The word “hall” appeared earlier, originally referring to the open part of a building in front of the inner chamber. The hall is orderly with flanking rooms on both sides, and there are houses and wings on both sides of the room. Such a group of buildings is collectively referred to as a hall, which refers to the residential buildings of the emperor, nobles, officials, and scholars. The word “palace” appeared later, originally referring to the high part at the back of a building, indicating its tall and prominent stature. Since the Han dynasty, the hall generally refers to the main building in government offices and private residences, but minor buildings in palaces and temples can also be called halls, such as the “east and west halls” in the palaces of the Northern and Southern dynasties, and the lecture halls and dining halls in temples.

Both halls and palaces can be divided into three basic parts: steps, body, and roof. Among them, the steps and roof form the most distinctive external features of Chinese architecture. Due to the constraints of feudal hierarchical system, there are differences in form and structure between halls and palaces. The difference in step-making between halls and palaces appeared earlier: halls only have steps, while palaces not only have steps, but also have terraces. In addition to the main platform itself, there is also a tall platform below it, connected by a long series of terraces.

The palace is generally located at the center or main axis of the architectural complex of palaces, temples, and royal gardens. Its plan is mostly rectangular, but also includes square, circular, and cross-shaped forms. The scale of the palace’s space and components is often larger, and the decorative methods are more exquisite. The hall is generally used as the main building in mansions, government offices, private residences, and gardens, with various plan forms, moderate volume, simple structural methods, and decoration materials, often exhibiting more local characteristics.

Lougé

A multi-story building in ancient Chinese architecture. Originally, there was a distinction between “lou” and “gé.” “Lou” refers to a heavy building, while “gé” refers to a building with an elevated lower structure. A typical gé has a nearly square plan, two stories, and a flat top, and is often located in a prominent position within a group of buildings, such as the Guanyin Pavilion at the Dule Temple. In contrast, a lou is often narrow and has a curved shape, and is usually located in a secondary position within a group of buildings, such as a sutra repository in a Buddhist temple or a rear building or wing in a palace.

In later times, the terms lou and gé became interchangeable and there was no strict differentiation between the two. Ancient lougé had various architectural forms and purposes. The city gate tower appeared during the Warring States period, and by the Han Dynasty, city gate towers had reached three stories in height. Quelou, market towers, and watchtowers were all popular forms of lougé in the Han Dynasty.

During the Han Dynasty, the emperor believed in the power of Taoist immortals and thought that building tall and lofty lougé could help him attain immortality. After the introduction of Buddhism to China, a large number of pagodas were built, which also served as lougé. The wooden pagoda of Yongning Temple in Luoyang, Northern Wei Dynasty, was more than 40 zhang (about 120 meters) high and could be seen from a hundred li (about 50 kilometers) away. The Shijia Pagoda in Ying County, Shanxi Province, built in the Liao Dynasty, is still the tallest ancient wooden structure in China, with a height of 67.31 meters.

Lougé used for sightseeing and leisure activities often have names like Huanghe Tower and Tengwang Pavilion. Most ancient Chinese lougé were made of wood and had various structural forms. Lougé with a square frame formed by intersecting and overlapping square timbers are called jǐngshí (井栏式); those built by stacking single-story buildings on top of each other are called zhòngwū (重屋式). Since the Tang and Song dynasties, a platform structure layer has been added between the floors, forming a hidden layer and a floor on the inside eaves, which extends outward to form a projecting platform. This form is called píngzuò (平坐) in the Song Dynasty. The columns between the upper and lower floors are not connected, and the connection between the structures is complex. The lougé structure of the Ming and Qing dynasties connected the columns of each floor into a continuous column, and they were connected to the beam and purlin to form an integral framework called tōngzhù (通柱式). There are also other variations of lougé structures.

Pavilion

A pavilion is a small, open-sided building found in traditional Chinese architecture. It is used for people to rest, view scenery, or for ceremonies. It emerged in the mid-late period of the Northern and Southern dynasties. The pavilion is usually located in scenic places such as hills, watersides, city walls, bridges, and gardens. There are also pavilions with specific functions, such as tablet pavilions, well pavilions, sacrificial pavilions, and bell pavilions. The plan of the pavilion can be square, rectangular, circular, polygonal, cross-shaped, linked, plum-shaped, fan-shaped, and more. The roof of the pavilion can be a gable and hip roof, a hipped roof, a conical roof, or a combination of different shapes. Large pavilions can have multiple eaves or a four-sided courtyard. The tablet pavilions and well pavilions in tombs and ancestral temples can be solemn, such as the tablet pavilion in the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum. Large pavilions can be majestic, such as the Wanchun Pavilion in Jingshan, Beijing. Small pavilions can be delicate and elegant, such as the Sanjiao Pavilion in Hangzhou’s Santiinyue. The different forms of pavilions can create different artistic effects. In terms of construction, the pavilion is mostly made of wood, but there are also brick and stone structures. The pavilion roof is mostly gable and hip roof or conical roof. The four-corner gable and hip roof appeared in the Han Dynasty, and the octagonal gable and hip roof and conical roof were found in Tang Dynasty Mingqi. The “doujian” structure described in the Song “Building Law” is a structure similar to an umbrella stand, which can be seen in southern gardens since the Qing Dynasty. After the Ming and Qing Dynasties, square pavilions mostly used sloping corners, and multi-corner gable and hip roof pavilions mostly used cantilevered brackets and were layered on top of each other. The construction of rectangular pavilions is basically the same as that of residential buildings.

Corridor

Corridors are covered passages in ancient Chinese architecture, including the hui (回) and you (游) corridors. Their basic function is to provide shade and protection from rain and to offer a place for people to rest. Corridors are an important component of the overall appearance of ancient Chinese architecture. The corridors under the eaves of halls serve as transitional spaces between indoor and outdoor areas and are an important means of creating variations in the structure and rhythm of a building. The enclosing corridors around courtyards play an important role in beautifying the layout and volume of the courtyard space, and can create different effects such as solemnity, liveliness, openness, depth, enclosure, and connectivity. The you corridors in gardens mainly serve to divide scenic areas, create various spatial changes, increase depth of field, and guide the optimal viewing route. Corridors are often decorated with geometric patterns on railings, benches, goose-neck chairs (also known as beauty chairs or Wuwang chairs), hanging decorations, and painted murals. Various decorative architectural elements such as mixed light windows, leaking windows, moon gates, and bottle-shaped doors are often used on partition walls.

Tai and Xie

In ancient China, a raised earthen platform was called Tai, and the wooden structure built on top of it was called Xie. Together they were known as Tai Xie. The earliest Tai Xie were simple, columned pavilions built on small earthen mounds, used for viewing, banqueting, and archery, and sometimes for moisture-proofing and defense. There are many remains of Tai Xie, including the famous Jin Dynasty Xintian site, the Yan Xiaodu site in the Warring States period, the Zhao Guo ancient city site in Handan, and the Xianyang Palace site in the Qin Dynasty, all of which have preserved huge stepped earthen platforms. Xie also refers to larger open-sided buildings. After the Tang Dynasty, buildings built by the water or in the water were called Shuixie, but they were already a completely different type of architecture from Tai Xie.

Temple

A type of solemn and orderly sacrificial building in ancient China, which can be roughly divided into three categories:

Ancestral temples for worshiping ancestors. The buildings where emperors, princes, and others offered sacrifices to their ancestors are called ancestral temples. The ancestral temple of an emperor is called the “Tai Miao,” with different specifications throughout history. The Tai Miao is the highest-ranked building. The ancestral temples or family temples where aristocrats, prominent officials, and large families worship their ancestors are called “Jia Miao” or “Zong Ci.” They are usually located on the east side of their estates, with different sizes. Some Zong Ci are also attached with schools, granaries, or theaters, which go beyond the scope of worship.

Temples for worshipping sages. The most famous is the Temple of Confucius, also known as the Wen Miao, which is dedicated to Confucius, the founder of Confucianism. After the Han Dynasty, emperors and kings have revered Confucianism. The Confucian Temple in Qufu, Shandong, is the largest. The temple for worshipping Guan Yu, a famous general in the Three Kingdoms period, is called the Guan Di Temple or the Wu Miao. In some places, the Three Loyalty Temple is built to worship Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei. Many places also worship famous statesmen, heroes, martyrs, and righteous people, such as the “Wu Hou Temple” in Chengdu, Sichuan, and Nanyang, Henan, which is dedicated to Zhuge Liang, a famous politician in the Three Kingdoms period.

Temples for worshipping mountains, rivers, and gods. Since ancient times, China has worshipped nature, such as heaven, earth, mountains, and rivers, and built temples for worship, such as the Hou Tu Temple. The most famous are the temples for worshipping the Five Sacred Mountains – Mount Tai, Mount Hua, Mount Heng, Mount Song, and Mount Hengshan. Among them, the Dai Temple of Mount Tai is the largest. There are also a large number of sacrificial buildings derived from various religions and folk customs, such as the City God Temple, Earth God Temple, Dragon King Temple, and God of Wealth Temple.

Altar

An altar is a platform-type building in ancient China used mainly for activities such as worshipping the heavens, the earth, and the gods of the soil and crops. The main altars in Beijing include the Altar of Heaven, the Altar of Earth, the Altar of the Sun, the Altar of the Moon, the Altar for Praying for a Good Harvest, and the Altar of the God of Agriculture. Altars were not only the main body of the sacrificial buildings, but also the general term for the entire group of buildings. The form of the altars was mostly based on theories such as yin-yang and the Five Elements. For example, the main buildings of the Altar of Heaven and the Altar of Earth are circular and square, respectively, based on the ancient Chinese concept of “heaven is round and earth is square.” The number and size of the stones used for the Altar of Heaven were all odd, in accordance with the ancient Chinese belief that odd numbers represent yang (positive energy) and heaven is yang. The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests has three layers of eaves, each covered with glazed tiles of a different color: green for the bottom, symbolizing all living things; yellow for the middle, symbolizing the earth; and blue for the top, symbolizing the sky. In the 16th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the color of all three layers was changed to blue to show the imperial family’s exclusive right to offer sacrifices to the heavens.

Pagoda

A pagoda is a tall, pointed building used for storing and enshrining Buddhist relics, statues, scriptures, and the remains of monks. It is also known as a “Buddhist pagoda” or a “treasure pagoda.” Pagodas originated in India and are also commonly referred to as “stupas,” “chedis,” or “tope.” Pagodas are one of the most numerous and diverse types of buildings in ancient Chinese architecture.

A typical pagoda consists of a ground floor chamber, a base, a main body, a roof, and a spire. The ground floor chamber houses the relics and is located in the center of the base below ground level. The base includes a foundation and a pedestal. The spire sits on top of the roof and is usually composed of a lotus throne, a canopy, a water pot, a parasol, and a jewel; some pagodas also include a pagoda crown, a circular halo, a moon disk, and a jewel.

There are many different types of pagodas in China, with over 2,000 still standing today. They can be classified according to their purpose, such as Buddhist pagodas or pagodas for high-ranking monks; by their construction material, such as wooden, brick, stone, metal, or ceramic; or by their structure and form, such as tower-style pagodas, multi-eaved pagodas, single-story pagodas, Lhoba pagodas, and other special designs. Famous tower-style pagodas include the Ci’en Temple Pagoda in Xi’an, the Xingjiao Temple Xuanzang Pagoda, and the Yunyan Temple Pagoda in Suzhou. Famous multi-eaved pagodas include the Songyue Temple Pagoda in Dengfeng, the Jianfu Temple Pagoda in Xi’an, and the Chongsheng Temple Qianxun Pagoda in Dali. Famous single-story pagodas include the Shentong Temple Four Gates Pagoda in Licheng, the Yunju Temple Stone Pagoda Group in Beijing, and the Jingshan Temple Jingzang Chan Master Pagoda in Dengfeng. Lhoba pagodas are traditionally painted white and are commonly known as “white pagodas,” with famous examples including the White Pagoda at the Miaoying Temple in Beijing and the White Pagoda at the Tafosi Temple in Wutai County, Shanxi. The Golden Summit Pagoda at the Zhengjue Temple in Beijing is a famous example of a pagoda with a diamond seat.

Ying bi

yǐng bì is a wall built inside or outside the gate of a courtyard as a barrier and a decorative element. It is also known as a “screen wall” or a “reflected wall”. The function of the shadow wall is to create a transitional space that connects the street and the courtyard while providing some degree of privacy. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the shadow wall took various forms, including the “one-character” and “eight-character” shapes. In Beijing, the eight-character wall is commonly used on both sides of the entrance to create a space slightly wider than the street. The one-character wall is used inside the gate and, together with the side walls and the screen door, forms a small courtyard. In rural areas, shadow walls are often built with rammed earth or adobe, with a tiled roof on top. Palace walls and temple walls are often decorated with glazed tiles. Famous examples of shadow walls include the Nine Dragon Wall in Datong, Shanxi Province, and the Nine Dragon Wall in Beihai and the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Fangbiao

Fangbiao is an ancient Chinese architectural structure that serves as a means of recognition, commemoration, guidance, or marking. It includes arches, pailous, and other similar structures. A pailou, also known as a paifang, is a type of structure with a single row of pillars that serves to divide or control space. If the pillars are topped with decorative elements such as an entablature but no roof, it is called a pailou; if a roof is added, it is called a pailou. The roof is commonly known as a “lou,” and if the pillars rise above the roof, it is called a “chongtian pailou.”

Pailous are often built at the entrances of palaces, gardens, temples, tombs, and other large building complexes, and are of a higher level of formality. Chongtian pailous are often built at key locations in towns and cities, such as at the beginning of major roads, intersections, bridge entrances, and shop fronts. The former serves as a prelude to the main building complex, creating a solemn, dignified, and profound atmosphere, and complementing the main building. The latter can enrich the streetscape and serve as a landmark. In some towns in Jiangnan, multiple pailous are built across the street to commemorate achievements or filial piety. In mountainous scenic areas, pailous are often built on mountain roads, serving as a prelude to temples and marking progress along the mountain path.

famous ancient chinese architecture

Chinese architecture encompasses a broad range of structures, including temples, palaces, gardens, pagodas, and various residential and commercial buildings. Here are some examples of notable Chinese architecture buildings:

The Great Wall of China: The Great Wall is one of the most famous structures in the world and was built to protect the Chinese Empire from invasions. It stretches more than 13,000 miles and is the longest wall in the world.

The Forbidden City: Located in Beijing, the Forbidden City served as the imperial palace for the Ming and Qing dynasties. It is a vast complex of over 900 buildings and was home to Chinese emperors for nearly 500 years.

The Temple of Heaven: This religious complex in Beijing was used by emperors to perform annual rituals to ensure good harvests. Its most famous structure is the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, a round building with a triple-eaved roof and intricate decorations.

The Summer Palace: Another Beijing landmark, the Summer Palace is a vast complex of lakes, gardens, and palaces that was used by emperors as a summer retreat. Its most famous structure is the Long Corridor, a covered walkway decorated with thousands of paintings.

The Terracotta Army: Although not strictly a building, the Terracotta Army is a collection of thousands of life-size terracotta figures buried with the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. The figures are arranged in military formation and are considered one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

The Yellow Crane Tower: Located in Wuhan, the Yellow Crane Tower is a historic pagoda that has been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. It is known for its stunning views of the Yangtze River and the surrounding area.

The Lingering Garden: This classical Chinese garden in Suzhou is renowned for its intricate design and use of water and rocks to create a serene and harmonious environment. It is one of the most famous gardens in China and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

These are just a few examples of the many incredible buildings and structures that make up traditional Chinese architecture. They reflect the country’s rich history, culture, and architectural traditions, and continue to inspire visitors from around the world.

how did chinese architecture influence other cultures?

Ancient Chinese architecture, as a treasure in the world’s architectural culture, not only has profound historical and cultural heritage, but also has had a profound impact on the world’s architectural history. This article will explore the influence of ancient Chinese architecture on the world from three aspects: architectural style, technology and craftsmanship, and cultural inheritance.

I. Architectural Style

The characteristic of ancient Chinese architectural style is the extensive use of wooden structures and roof purlins. Through the use of mortise and tenon technology, various structural components are interlocked, ultimately forming a strong overall structure. This architectural style has not only been fully developed in the long history of China but has also had a profound influence on the world’s architectural history.

The most representative examples are the architecture of Japan and the Korean Peninsula, which are influenced by ancient Chinese architecture in both structure and decoration. Japanese temples, castles, tea houses, as well as Korean palaces, temples, and tombs, all make extensive use of Chinese traditional architectural techniques and components, such as mortise and tenon structures, dougong brackets, stone carvings, and painted decorations. In addition, there are also some buildings in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia that adopt Chinese traditional architectural styles, such as Malaysian wooden houses, Thai pagodas, and Cambodia’s Angkor Wat.

II. Technology and Craftsmanship

Ancient Chinese architecture has also had a profound impact on the world’s architectural history in terms of building technology and craftsmanship. The mortise and tenon structure, dougong brackets, brick and tile, painted decorations, and other techniques and crafts used in ancient Chinese architecture have not only been widely used in China but have also been promoted and applied worldwide.

For example, the mortise and tenon structure has been applied not only in the architecture of countries such as Japan and Korea but also in wooden structures worldwide. The dougong bracket technique has also been used in the architecture of India, the Middle East, and Europe. China’s brick and tile technology has also been applied in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia.

Secondly, ancient Chinese architecture emphasizes the use of mortise and tenon joints and strives for simplicity and elegance. This structural form has also had a wide influence on world architecture. In European architecture, many buildings have adopted the structural form of Chinese architecture, such as the Arc de Triomphe in France and the Washington Monument in the United States.

Chinese traditional architecture has unique characteristics in construction, decoration, materials, etc., which have had a profound influence in East Asia and also provided inspiration for Western culture. For example, in 18th-century Europe, the “Chinese style” became popular, with some Chinese elements being used in architecture, painting, clothing, etc. This shows that Chinese traditional architecture has played a very important role in promoting world cultural exchange.

In summary, ancient Chinese architecture has an irreplaceable position and role in world architectural history. Its unique architectural style and structural form, as well as its promotion of world cultural exchange, are valuable contributions to world architectural culture.

In addition, Chinese craftsmen innovated many tools and techniques during the construction process, such as cranes, wheels, pulleys, bridges, and fastening devices. The invention and application of these technologies provided more efficient, safer, and more precise methods for building engineering.

Furthermore, Chinese building materials and techniques have spread to other countries through trade and travel. For example, Chinese tiles and roof tiles have become a characteristic feature of many buildings in East Asia and Southeast Asia, and China’s wood construction technology has also been widely used in Japan and Korea.

Under the influence of ancient Chinese architecture, many other cultures’ buildings have developed their own characteristics and styles. In Japan, the Tang Dynasty’s architectural style influenced early temples and palaces, such as the Todaiji Temple and the Heijo Palace in Nara. In Korea, the Tang Dynasty’s architectural technology and style were applied to many palace and temple buildings, such as the Hongbeopsa Temple and the Yeongju Palace in the Goryeo Dynasty. In Vietnam, the influence of ancient Chinese architecture can be seen in the walls, palaces, and temples of many ancient cities, such as the Thang Long Citadel in Hanoi and the Phuc Kien Palace in Da Nang.

In conclusion, the influence of ancient Chinese architecture on world architecture is profound and extensive. It has not only influenced the architectural style and technology of neighboring countries but also provided inspiration and innovative ideas for architects and engineers around the world.

Chinese ancient architecture has had a profound impact on the world, both in terms of architectural innovation and cultural transmission. Elements and techniques of Chinese traditional architecture have been widely used in countries such as Japan and Korea, forming unique architectural styles that have had a far-reaching influence on later architecture and art.

As one of the representatives of Chinese traditional culture, traditional Chinese architecture has also been widely disseminated around the world, becoming an important window for Chinese culture on the international stage.

In terms of architectural design and materials, Chinese ancient architecture introduced many new technologies and materials, which not only improved the practicality and aesthetic value of architecture, but also became important foundations for later architecture. For example, the courtyard and garden design of Chinese traditional architecture has had a widespread influence on the architecture and garden design of countries such as Japan and Korea, becoming an important component of East Asian traditional architecture.

In modern architecture, Chinese ancient architecture has also become a source of inspiration and a reference for many architects’ design concepts. For example, the French architectural master Le Corbusier studied Chinese traditional architecture and garden design in depth, integrating some of the elements into his own architectural design and creating famous works such as the “Venice Yard”, which had an important influence on the development of modern architecture.

In summary, the impact of Chinese ancient architecture on the world is profound and extensive. It has played an important role not only in architectural design and materials, but also in cultural transmission. It has not only left a precious heritage for Chinese history and culture, but also provided important references and inspiration for world culture and architectural history.

In addition, the influence of ancient Chinese architecture on the world can be seen in cultural exchanges and the dissemination of architectural technology.

In ancient China, the skills of architects and craftsmen were passed down through apprenticeships. Through trade and cultural exchanges on the Silk Road, Chinese architectural technology and concepts were spread to Central and West Asia. The most famous example is the influence of the Tang Dynasty’s Daming Palace, which became a model for palace architecture in Central Asia and the Islamic world. The layout of Chinese palaces was adopted by Islamic dynasties in Samarkand, and artistic forms such as ceramic tiles, murals, and roof tiles in Central Asia were deeply influenced by Chinese culture.

Natural materials such as wood, stone, earth, and bamboo were widely used in ancient Chinese architecture, and their application and combination with other materials provided inspiration for innovations in world architecture. For example, Chinese wood construction and stone carving techniques were widely used in Japanese and Korean architecture, such as temples in Japan and palaces in Korea. These are important contributions of Chinese architecture to the world.

Overall, the influence and contribution of ancient Chinese architecture to the world cannot be ignored. As an important part of traditional Chinese culture, its influence and value far exceed the scope of architecture itself. It is an important bridge for the inheritance of Chinese civilization and cultural exchanges with the world.

In particular, it influenced the architectural styles of neighboring countries such as Japan and the Korean Peninsula. For example, traditional Japanese architecture, known as “Washiki architecture,” developed based on ancient Chinese architecture. They share the common features of using wood and bamboo as the main materials, adopting sloping roofs and suspended beam structures, and having similar roof forms and painted styles. Traditional Korean architecture was also deeply influenced by ancient Chinese architecture, especially in the construction of palaces and castles. Korean palaces and castles adopted traditional elements of Chinese architecture, such as torii gates, pavilions, and stone bridges.

The influence of ancient Chinese architecture is not only widely present in China, but also deeply affects the architectural styles and culture of neighboring countries and regions. This influence is not only reflected in the form and structure of architecture, but more importantly, in the philosophical thoughts and cultural connotations it embodies. It provides people with a rich cultural heritage and valuable historical heritage and plays a positive role in promoting the development of world architectural culture.

For example, in the Tang Dynasty, Chinese porcelain technology was already very mature and was applied to architecture, becoming an important form of roof tiles. This technology later spread to Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia, and other places, greatly influencing local architecture.

Overall, the influence of ancient Chinese architecture on the world can be said to be profound and extensive. From ancient palaces and temples to modern skyscrapers and residential buildings, the influence of ancient Chinese architecture can be seen in architecture all over the world. Ancient Chinese architecture is not only a unique cultural heritage, but also a very precious treasure of human civilization, worthy of our careful research and inheritance.

Elements of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Rules and Proportions

These are the common principles that determine the scale and proportion of various parts of the building. These rules establish the overall proportional and dimensional relationships between different parts of the ancient architecture. It is a key principle that ensures that various forms of architecture maintain a unified style.

Essential Components

These include the width and depth of the building, the height and diameter of the columns, the relationship between the width and height, the eave brackets and corner brackets, the relationship between the upper and lower parts of the building, the step brackets and the lifting brackets, the height of the platform and the slope of the roof, and the balance and proportion of the various components of the building.

Width and Depth

Four columns form a single room, and the width of the room is known as the “width,” or “span,” while the depth is known as the “depth.” The sum of the widths of several single rooms constitutes the total width of a building, known as the “overall width,” while the depth of several single rooms constitutes the overall depth of a single building.

The determination of the width of an ancient building (referring to the width of a single room) must take into account many factors, including actual needs (i.e., the principle of applicability), actual possibilities (such as the length and diameter of timber), and the restrictions of the feudal hierarchy.

In ancient times, the determination of the width of a room was also bound by feudal ideology. When considering the width of a room, the door size must be used to meet the size of the “official,” “salary,” “wealth,” “justice,” and other auspicious characters on the door. The width of the secondary room is generally 8/10 of the width of the main room, or determined according to actual needs.

Column Height and Diameter

The height and diameter of columns in ancient architecture have a certain proportional relationship, and there is also a certain proportion between the height of the column and the width of the room. For small-scale buildings, such as long-beam or six-beam small-scale buildings, the ratio of the width of the room to the height of the column is 10:8, which is commonly known as a width of one zhang and a column height of eight chi. The ratio of column height to diameter is 11:1. For example, according to the regulations of the Qing Dynasty’s Ministry of Public Works, “For all eave columns, the height is determined by 8/10 of the width of the span, and the diameter is determined by 7/100. For example, if the width of the span is one zhang and one chi, the column height can be eight chi and eight inches, and the diameter is seven inches and seven minutes.” For five-beam or four-beam small-scale buildings, the ratio of the width of the room to the height of the column is 10:7. Based on these regulations, one can calculate the column height by knowing the width of the room or the width of the room by knowing the column height and diameter.

Tapering and Footing

In ancient Chinese architecture, the diameters of the top and bottom of a round column are not equal, except for short columns such as melon-shaped columns. Instead, the column is slightly thicker at the base (footing) and slightly thinner at the top (capital). This technique is called “tapering” or “footing”. Tapering makes the column stable and lightweight, giving people a comfortable feeling.

The size of the tapering for different types of buildings is generally 1/100 of the column height. For example, if the column height is 3 meters, the tapering is 3 centimeters. Assuming the diameter of the base is 27 centimeters, the diameter of the top after tapering would be 24 centimeters. For larger buildings, the tapering is regulated as 7/1000 by “Yingzao Fashi” (the most authoritative book on ancient Chinese architecture).

Eaves and Cornices

In ancient Chinese architecture, the eaves are deep and project outward. The size of the eaves is also regulated. According to the Qing style, the size of the upper eaves (also called “outward eaves”) is measured horizontally from the middle of the eave beam to the outermost surface of the rafter (or to the outermost surface of the ridge beam if there is no rafter). Since the eaves are designed to shed water, the upper eaves are also called “water eaves”. For buildings without a dougong (a bracket system used in ancient Chinese architecture), the size of the upper eaves is set as 3/10 of the height of the supporting columns. For example, if the height of the columns is 3 meters, the upper eaves are divided into three equal parts, with the rafter extending two parts and the purlin extending one part.

Ancient Chinese buildings are built on raised platforms, and the visible part of the platform above the ground is called the “tai ming”. For small buildings, the height of the tai ming is 1/5 of the height of the columns or twice the diameter of the columns.

The part of the tai ming that extends outward from the supporting columns is called the “tai ming outward edge”, which corresponds to the upper eaves of the roof and is also called the “lower eaves”. The size of the lower eaves for small buildings is set as 4/5 of the upper eaves or twice the diameter of the columns. For larger buildings, the height of the tai ming is regulated as 1/4 of the distance from the upper surface of the tai ming to the lower surface of the roof ridge. The size of the tai ming outward edge for larger buildings is set as 3/4 of the upper eaves.

The upper eaves are larger than the lower eaves, and there is a difference in size between them, which is called the “cornice return”. The function of the cornice return is to prevent water from flowing onto the tai ming, thus protecting the footing of the columns and the walls from erosion by rainwater.

Purlin and Rafter

Purlin, in the wooden structure of Qing-style ancient architecture, refers to the horizontal distance between the middle of adjacent two rafters. Purlins can be divided into different types based on their position, such as porch purlin, ridge purlin, and so on. For a double-ridge awning architecture, the top central purlin is called the “top purlin.” Except for porch purlin and top purlin, the dimensions of other purlins in the same building are generally the same, with minor variations.

The size of a small porch purlin is usually 4D-5D, while the ridge purlin is generally 4D. The size of the top purlin is usually smaller than that of the ridge purlin. For a four-purlin awning, the size of the top purlin is usually determined by dividing the size of the middle purlin of each end into five equal parts, with the top purlin occupying one part and the porch purlin occupying two parts. The size of the top purlin should not be smaller than 2D or larger than 3D, but can be adjusted within this range.

Rafter refers to the ratio of the vertical distance (elevation) between the middle of adjacent two rafters to the length of the corresponding purlin. The Qing Dynasty architecture commonly used different ratios, such as five-rafter, six-five-rafter, seven-five-rafter, and nine-rafter, indicating the ratios of 0.5, 0.65, 0.75, and 0.9, respectively. The porch (or gallery) purlin made in the Qing style is generally set to five-rafter and called the “five-rafter head.”

For small houses or garden pavilions, the porch purlin can also be set to four-five-rafter or five-five-rafter, depending on the specific situation. The ridge purlin of a small house is generally not more than eight-five-rafter, while that of a large building is generally not more than ten-rafter. The variation of the rafter in ancient architecture determines the quality of the roof curve, so the use of rafter should be very careful, paying attention to the effect of the roof curve to make it natural and smooth.

For thousands of years, the craftsmen of ancient architecture have accumulated a set of successful experiences in using the rafter and formed a relatively fixed program. For example, for a small five-purlin house, the porch purlin is generally set to five-rafter, and the ridge purlin is set to seven-rafter. For a seven-purlin house, the steps are usually five-rafter, six-five-rafter, and eight-five-rafter, respectively. The size of each step in a large building can be in order of five-rafter, six-five-rafter, seven-five-rafter, and nine-rafter, etc.

Chinese influence on Japanese architecture

The Tang Dynasty was one of the most prosperous periods in Chinese history. It embraced various ethnic groups from inside and outside of the country for exchange and learning, and its open international diplomacy made “Great Tang” reputation spread far and wide. Nowadays, many overseas countries still refer to Chinese people as Tang people. The cultural and artistic achievements of the Tang Dynasty reached their peak during this flourishing era of the Central Plains civilization. Although Japan, as a neighboring country, had been influenced by Chinese culture since the Han Dynasty, it was not until the Tang and Song Dynasties that it was attracted to the flourishing Chinese culture and dispatched a large number of envoys to learn and imitate it comprehensively.

1.1 Spread of Chinese Tang-style architecture

Among many cultural transmissions, architectural culture is particularly prominent because it is a tangible display. At that time, large wooden architecture reached its peak in both craftsmanship and artistry. However, unfortunately, only four Tang Dynasty buildings remain in China today, while Japan, due to proper preservation, has retained many buildings deeply influenced by ancient Chinese culture. Because of the special attributes of religious architecture, the building types that have been preserved in both China and Japan are mostly temple buildings.

1.2 Presentation of Chinese Tang-style architecture

The Tang Dynasty is far away from us now, and to perceive the cultural charm of that time, we can only search for it from the few remaining works of art and historical records. Most of the existing ancient buildings are mainly from the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Film and television can be said to be one of the windows for spreading culture and inheritance, although there are good and bad works. The “Tang City” built for the movie “The Legend of the Demon Cat” in Xiangyang can be regarded as a rare masterpiece in recent years and a groundbreaking work. Prior to this, most film and television works depicting the Tang and Song Dynasties were filmed in Japan. “Tang City” basically restores the ancient city style of the Tang Dynasty. Although there are some inaccuracies in the construction, it is already meticulous enough for film and television works and marks a step forward in the study of Tang Dynasty architecture beyond physical objects. Scholars and the public can directly access the form of Tang Dynasty architecture, making it easier to understand the cultural style of the Tang and Song Dynasties in China. The Zhuque Gate and Hanyuan Hall in “Tang City” are both built according to historical records in a 1:1 ratio. The curved roofs, powerful brackets, deep eaves, flat ceiling patterns, and straight windows of the buildings in “Tang City” form the distinctive structural beauty of Tang Dynasty architecture. Due to the close connection between traditional Japanese architecture and Tang Dynasty architecture, some decorative components of traditional Japanese architecture were borrowed in the design and construction of “Tang City”. For example, the golden chimaera on the palace roof in “Tang City” is almost identical to the chimaera on the roof of Todai-ji Temple in Nara, Japan. Although it does not match the architectural style of that time, it shows that traditional Japanese architecture is a reference for the study of Tang Dynasty wooden architecture.

The reflection of Chinese Tang-style architectural features in Japanese traditional architecture

Japan places more emphasis on the spiritual expression of traditional architecture in its preservation efforts. Therefore, most of the existing traditional buildings in Japan have been restored. However, the spiritual ambiance and main components of these buildings have been preserved, and we can still find the influence of Chinese Tang-style architecture in them.

2.1 The layout of Tang-style architecture in Japanese traditional buildings

The capital city of Chang’an during the Tang Dynasty had a magnificent, symmetrical, and orderly layout with a chessboard-like design. The north-south axis was dominated by Zhuque Street, with the east and west markets located on either side. This city layout also had a significant impact on Japan, with Nara and Kyoto both modeled on the planning layout of Chang’an. The same applies to architecture. Horyuji Temple, built in 596 AD, adopts a symmetrical axis layout with the main hall, pagoda, and central gate in front of the main hall and the hall behind the main hall serving as the central axis of the entire temple. The east and west halls are located on either side of the pagoda, and a corridor running through the central gate connects the three halls to form a courtyard.

2.2 The design of Tang-style architecture in Japanese traditional buildings

The Todai-ji Temple is a representative temple, and Liang Sicheng once said, “There is no better reference for the study of Chinese Tang-style architecture than the Golden Hall of the Todai-ji Temple.” It is located on Gojo Street in Nara, Japan and was built in 759 AD by the Chinese Tang Dynasty monk Jianzhen during his sixth trip to Japan. As the Todai-ji Temple was actually built by Tang people, the entire architecture basically restored the style of Chinese Tang-style architecture. The exterior of the Golden Hall is highly similar to that of the main hall of Foguang Temple in Wutai Mountain, Shanxi Province. Although the main hall of Foguang Temple was built almost a hundred years after the Golden Hall, they have very similar structures. Both the exterior and interior of the halls have a similar appearance and style, which is the style of Tang Dynasty architecture. The Golden Hall has a frontage of seven bays and a side length of four bays, and is located on a one-meter-high stone platform. The single-eave roof has large bracket sets, deep eaves, and thick, tapered columns. The windows are latticed, serving both as light sources and decorations. The hall is mainly red and white, with colorful patterns painted on the exterior, while the pillars, beams, and ceiling inside are painted with colorful patterns, retaining the distinctive features of Tang Dynasty architecture.

Continuity and Development of Tang Dynasty Culture in Japanese Traditional Architecture

3.1 Changes in Architectural Layout

China, influenced by Confucian hierarchical thinking, values symmetry and presents a courtyard layout with a central axis. Japanese architecture gradually broke away from this strict symmetry. By the 13th century, most buildings adopted the Japanese-style asymmetric layout. Horyu-ji Temple, founded in 607 AD, is a prominent example. Although the initial construction of Horyu-ji Temple imitated the central axis distribution of Chinese architecture, the strict symmetrical layout gradually disappeared over time as the temple underwent expansion, renovation, and repair, resulting in an asymmetric layout with buildings leaning towards one side. The layout of the Goju-no-to (five-story pagoda) and Kondo (main hall) arranged horizontally is almost nonexistent in Chinese temples.

3.2 Development of Architectural Style

Many of the Tang Dynasty style scenes in Chinese films are actually filmed in Japan. At first glance, there is little discrepancy, but upon closer inspection, the differences become apparent. Although Japanese traditional architecture follows the mortise and tenon structure of Chinese traditional architecture and imitates the forms of architectural components such as bracket sets, beams, columns, and doors and windows, it presents a more simplified and plain style. The architectural style of not applying red lacquer to the pillars and the cloud-shaped bracket sets with their tops exposed, which incorporate building materials into the building decoration, is markedly different from that of Chinese Tang Dynasty architecture. Chinese architecture underwent significant changes after the Ming Dynasty, with architectural style becoming luxurious and rich, and architectural components becoming decorative. Tang Dynasty style architecture gradually declined and disappeared. Japan, on the other hand, did not continue to imitate Tang Dynasty architecture, but rather integrated its own national attributes based on the culture of Tang and Song Dynasty architecture, developing its unique Japanese style architecture. Nijo Castle, built during Japan’s Edo period, is the masterpiece of Japanese architectural aesthetics and was the residence of the Tokugawa shogunate in Kyoto. The entrance gate is decorated with gold leaf, with exquisite carvings of dragons, cranes, and other animal ornaments. The gate is called the Tang Gate, but it has little to do with Tang Dynasty architecture. The name may have come from the arch-shaped “Tang windbreaker” on top of the gate. The Tang windbreaker’s origin in China is still uncertain, but it is undoubtedly a representative decorative element in Japanese architecture. The roofs of the imperial palace buildings inside the castle resemble “hip-and-gable” roofs and are combined with Japanese-style decorative elements. At this time, Japanese architectural imagery had little to do with Tang Dynasty architecture.

From the above discussion, it can be seen that Tang Dynasty architecture is rare in modern-day China and has limited historical records. Studying how Tang Dynasty architectural style is reflected in Japanese traditional architecture can better help us research the architectural culture of Tang and Song dynasties in China. Especially for the few ancient temples still existing in Japan, from architectural components to building decorations, they still retain obvious characteristics of Tang Dynasty architecture, providing material evidence for our research on the architectural culture of Tang and Song dynasties. Although Japanese architecture fully absorbed the technical forms of Tang Dynasty architecture in China, and combined them with their own cultural background to create unique architectural styles, we can still explore the architectural culture of China’s Tang and Song dynasties through a comparison of these changes and developments.

Chinese architecture roof

Roofing in traditional Chinese architecture is one of its most distinctive features. Chinese roof architecture has a long history and has evolved over time with regional variations. The roofs are typically pitched and curved, with the most common shape resembling the character for “人” (rén) meaning person or man.

The roof is made up of several components, including the roof ridge, roof tiles, eaves, brackets, and the gable end. The roof tiles are typically made of clay, but other materials such as wood, glazed tiles, or even stone may be used in certain regions. The tiles are laid in an overlapping pattern to create a watertight seal and prevent rainwater from entering the building.

The eaves are an important component of Chinese roofs and extend outwards from the building to provide shade and protection from rain. The size of the eaves can vary depending on the region and the function of the building. In some areas, the eaves are so large that they can provide shelter for people walking on the street below.

Another important feature of Chinese roof architecture is the use of brackets or dougong, which are wooden or stone components that support the roof structure. The brackets are often intricately carved with decorative motifs and can be a work of art in their own right.

The gable end, which is the triangular section of the wall located above the roofline, is also an important feature of Chinese roof architecture. It is often decorated with carvings or painted with elaborate designs, and can be a symbol of wealth and status.

Overall, Chinese roof architecture is a beautiful and functional art form that reflects the ingenuity and craftsmanship of Chinese builders and artisans. It has played an important role in shaping the distinctive character of Chinese architecture and is a source of pride for the Chinese people.

why are the rooftops sloped in Japanese and Chinese architecture?

Due to the prevalence of wooden structures in traditional Chinese architecture, buildings could not exceed the natural height of a single tree. However, to showcase the power and authority of ancient Chinese emperors, the eaves became the only way to express this, making the roof the dominant feature in traditional Chinese architecture. The beautiful curvature of the roof ridge also became a symbol of aesthetics. During the medieval era, especially in the prosperous Tang Dynasty, many Tang Dynasty-style buildings were built in Kyoto and other places after the arrival of Tang envoys studying in China, resulting in roofs that followed this style. (The horizontal ridge is the main ridge, and the oblique ridge is the secondary ridge. If the building has multiple eaves, it may also have surrounding ridges and hanging ridges, etc.)

Japanese culture has been deeply influenced by Chinese culture, and its architecture is no exception, especially in medieval Japanese architecture. It can be divided into three styles: Japanese-style, Tang-style, and Indian-style architecture, but in fact, these architectural styles all originated from China. Japanese-style architecture mainly inherits the Tang Dynasty architectural style from the Feiyan and Nara periods and incorporates some early Shinto shrine elements. Representative works include the Bell Tower of the Todai-ji Temple in Nara (1240) and the main hall of the Renge-ō-in Temple in Kyoto (1266). Temples are the representative of Japanese-style architecture, which can be found all over Japan, from bustling cities to remote villages. Compared with Chinese temples, Japanese temples tend to be more elegant, and the color is not as colorful. The deep eaves of the roof are a typical Chinese style because Japanese temple architecture is modeled on the architecture of the Tang Dynasty in China, while the temples seen in China today are mostly of Ming and Qing Dynasty styles. Tang-style architecture originated from the architectural styles of the Song and Yuan dynasties in China. The Zen sect of Song and Yuan culture had the greatest influence on Japanese medieval culture, so Tang-style architecture is also known as Zen-style architecture. The introduction of Chinese culture not only enriched Japanese religious culture but also ushered in a new era of Japanese architectural culture.

The form and slope of the sloping roof depend mainly on factors such as building plan, structural form, roofing material, climate environment, customs, and architectural style. The main types are single-sloped, double-sloped, four-sloped, and hipped roofs. Double-sloped and four-sloped roofs are more commonly used.

what is the difference between Japanese and Chinese architecture?

Japanese architecture has been influenced by Chinese architecture throughout history, but there are some differences between the two styles.

One major difference is the materials used. Traditional Chinese architecture often used wood as the primary building material, while traditional Japanese architecture used more natural materials such as wood, bamboo, and paper.

Another difference is the shape of the roofs. Chinese traditional architecture often features curved, sweeping roofs with upturned eaves, while Japanese traditional architecture often features steeply pitched roofs with deeply overhanging eaves.

In terms of layout, Japanese architecture is known for its emphasis on nature and the surrounding environment, often incorporating gardens and open spaces within the design. Chinese architecture, on the other hand, is more focused on symmetry and balance, with the layout based on a strict grid system.

Finally, there are differences in the decorative elements used in each style. Chinese architecture often features intricate carvings and decorations, while Japanese architecture often employs more subtle and understated decorative elements such as shoji screens and tatami mats.

Overall, while there are similarities between Chinese and Japanese architecture, each style has its own unique characteristics and cultural influences.

what influenced Chinese architecture?

Chinese architecture has been influenced by various factors throughout history, including:

Geographic and climatic conditions: The vast and diverse geography and climate of China have played a significant role in shaping its architecture. Different regions of China have distinct architectural styles that reflect their unique environments and cultural histories.

Religious and philosophical beliefs: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism have all had a profound impact on Chinese architecture. These belief systems have influenced architectural design, symbolism, and the use of materials.

Imperial power and dynastic change: Chinese architecture has been shaped by the dynastic changes and imperial power struggles throughout history. Each dynasty had its own architectural style and techniques that reflected its unique cultural and political values.

Foreign influences: China has been influenced by various foreign architectural styles, including Central Asian, Indian, and European styles. These influences have been incorporated into Chinese architecture to create new styles and techniques.

Artistic and aesthetic traditions: Chinese architecture is closely tied to the country’s artistic and aesthetic traditions, including calligraphy, painting, and sculpture. These traditions have influenced architectural design and decoration.

Overall, Chinese architecture is the result of a complex and rich cultural history that has evolved over thousands of years.

how did religion influence Chinese architecture?

Religion has had a significant influence on Chinese architecture throughout history. Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism are the three major religions that have influenced Chinese architecture the most.

Buddhism was introduced to China from India during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), and it had a profound impact on Chinese architecture. Buddhist architecture in China includes pagodas, temples, and grottoes. Buddhist pagodas were originally used to store Buddhist scriptures and relics, but they later became places of worship. Many of the famous pagodas in China were built during the Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1279 CE) dynasties.

Taoism, an indigenous Chinese religion, emphasizes harmony with nature and the balance of opposites. Taoist architecture often features gardens, courtyards, and natural materials such as wood, stone, and bamboo. The Taoist concept of yin and yang is also reflected in the design of buildings, with the use of contrasting colors and shapes.

Confucianism, another indigenous Chinese religion, emphasizes the importance of education, social order, and filial piety. Confucian architecture includes ancestral halls, temples, and academies. Ancestral halls were built to honor ancestors and to provide a place for family members to pay their respects. Confucian temples were dedicated to Confucius and other sages and were used for education and ritual ceremonies. Confucian academies were also used for education and were important centers of learning during the Ming (1368-1644 CE) and Qing (1644-1912 CE) dynasties.

how did Buddhism influence Chinese architecture?