The Chinese culture is rich in symbolism and carries deep meanings in various aspects of life, including animals. In Chinese folklore, animals are often associated with specific traits and symbolism. In this article, we will explore the meaning of cows in Chinese culture, their significance, and the symbolism they hold.

does Cow live in China?

Cows do live in China. Cattle farming and husbandry have a long history in China, and cows are reared in various regions across the country. They are primarily found in rural areas where agriculture and livestock farming are practiced. The specific breeds of cows found in China may vary, but common breeds include the Chinese Yellow Cattle and the Tibetan Yak, which is also considered a type of cow. Cows are utilized for their milk, meat, and as working animals in farming activities.

how many cows in China?

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the overall trend of cattle inventory in China has shown fluctuating growth from 2016 to 2021. In 2021, the cattle inventory in China reached 98.17 million heads, which was an increase of 2.55 million heads or 2.67% compared to 2020.

what kinds of Cow live in China? (Chinese cow breeds)

Chinese Yellow Cattle:

Mongolian Cattle: Mainly found in Inner Mongolia, with distribution in northeastern, northern, and northwestern provinces of China.

Qinchuan Cattle: Originates from the Wei River basin in Shaanxi province, particularly famous in seven counties including Xianyang, Xingping, Wugong, Liquan, Qianxian, Fufeng, and Weinan.

Nanyang Cattle: Found in the Nanyang region of Henan province, known for their large size, sturdy build, and excellent work performance.

Luxi Cattle: Found in Jining and Heze regions of Shandong province.

Yanbian Cattle: Found in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture of Jilin province.

Southern Cattle: Distributed in southern provinces, the Yangtze River basin, Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Taiwan. They vary in size and color, with larger sizes in plain areas and smaller sizes in mountainous regions.

Water Buffalo:

Chinese Water Buffalo: Distributed in rice-growing regions south of the Huai River, from Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan to southern Shaanxi. Also found in Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangdong, Guangxi, Zhejiang, Fujian, Taiwan, and other provinces and regions. Chinese water buffaloes are known for their robust physique, strong endurance, and high work capacity.

Murrah Buffalo: Originally from India, Murrah buffaloes have a strong build, well-developed muscles, and high milk production. They are used to improve the local Chinese water buffalo breed.

Dairy Cattle:

Holstein Friesian: Originally from the Netherlands, Holstein Friesian cows are widely distributed globally and known for their high milk production.

Beef Cattle:

Charolais: Originating from the Charolais region in France, Charolais cattle are characterized by their large size, strong muscles, and fast growth. They are often crossed with Chinese local yellow cattle for improved growth rates.

Hereford: Originally from Herefordshire, England, Hereford cattle are known for their strong constitution, adaptability to coarse forage, and early maturity. They are commonly used for crossbreeding in China.

Angus: Originating from Scotland, Angus cattle have a solid black coat and are known for their meat quality, adaptability, and high carcass yield.

Tibetan Yak: Unique to high-altitude regions in Tibet and western China, Tibetan Yaks have long, shaggy hair, large horns, and are primarily used for milk, meat, and fiber production.

what are Chinese cows called?

- “犊” (dú) refers to a young cow or calf. “犝” (tóng) refers to a young cow without horns. “牬” (bèi) refers to a two-year-old cow. “犙” (sān) refers to a three-year-old cow. “牭” (xíng) refers to a four-year-old cow and can also denote a fierce or aggressive cow. “犕” (bèi) refers to an eight-year-old cow.

- “犣” (liè) refers to mature bulls or oxen, specifically referring to the yak. “犛” (máo) is an ancient term meaning the same as “牦” (máo), which refers to yaks. “牥” (fāng) refers to a mythical cow in ancient legends that was said to be able to travel long distances in the desert, similar to a camel.

- “乌犍” (wū jiān) is a term that generally refers to draft cattle. “沈牛” (shěn niú), also known as “沉牛” (chén niú), specifically refers to water buffalo.

- Different age stages of cows have different names, such as “犊” (dú) for a calf, “牬” (bèi) for a two-year-old cow, “犙” (sān) for a three-year-old cow, “牭” (xíng) for a four-year-old cow, and “犕” (bèi) for an eight-year-old cow.

- Other names for cows include “丑牛” (chǒu niú), “土畜” (tǔ chù), “乌犍” (wū jiān), and “沈牛” (shěn niú).

Cow in Chinese culture

In Chinese culture, the cow holds significant symbolism and plays a notable role in various aspects of traditional beliefs, folklore, and customs. Here are some key associations and meanings of the cow in Chinese culture:

Hardworking and Diligence: The cow is seen as a symbol of hard work, diligence, and perseverance. This stems from its historical significance as an essential agricultural animal used for plowing fields and carrying heavy loads. The diligent nature of cows has been admired and incorporated into Chinese cultural values, encouraging people to emulate their industriousness.

Agricultural Prosperity: Cows are closely linked to agricultural prosperity and the importance of farming in Chinese society. They symbolize fertility, abundance, and bountiful harvests. In traditional festivals and rituals, cows are often honored to seek blessings for a prosperous agricultural year.

Harmony with Nature: Cows are associated with a harmonious relationship between humans and nature. They are viewed as gentle and docile creatures, living in harmony with the natural environment. This concept aligns with the Chinese philosophy of maintaining balance and respect for the natural world.

Zodiac Sign: In the Chinese zodiac, the cow is one of the twelve animal signs. People born in the Year of the Cow (or Ox) are believed to inherit the cow’s characteristics, such as being hardworking, dependable, and methodical. The Year of the Cow is considered auspicious for agricultural activities, business ventures, and building foundations.

Symbol of Wealth and Prosperity: Owning cows has long been considered a symbol of wealth and prosperity in rural communities. Cattle were seen as valuable assets, providing dairy products, meat, and labor. In traditional Chinese folklore, the image of a prosperous household often includes the presence of cows.

Feng Shui Symbolism: In Feng Shui, the cow is associated with abundance, good luck, and protection. Cow figurines or artwork are sometimes used to enhance positive energy and attract prosperity into homes and businesses.

Overall, the cow holds a positive and revered position in Chinese culture, representing hard work, agricultural abundance, harmony with nature, and prosperity. Its symbolism reflects the deep-rooted connection between Chinese society, agriculture, and traditional values.

are cows sacred in China?

Cows do not hold a significant level of sacredness or religious significance in traditional Chinese culture compared to some other cultures like Hinduism in India. In China, certain animals like dragons, phoenixes, and turtles have traditionally held more symbolic and auspicious meanings. However, cows do have practical and cultural importance in China as a source of agricultural labor, dairy products, and meat.

In Chinese agriculture and rural life, cows have been valued for their strength and ability to assist with farming tasks such as plowing fields. Historically, they played an essential role in the agricultural industry and were highly regarded as working animals.

It’s important to note that China is a diverse country with various cultural beliefs and practices, and there may be certain regions or ethnic groups within China where cows have a more symbolic or religious significance. However, in mainstream Chinese culture, cows are primarily seen as useful livestock rather than objects of worship or sacredness.

what does the cow mean in Chinese culture?

- Cows, with their willingness to work tirelessly without complaint, symbolize sincerity, authenticity, simplicity, and kindness.

- The term “牛人” (niú rén), meaning “cow person,” is commonly used to describe someone who is highly talented and capable.

- Cows, with their strong physique and generally robust health, symbolize good physical health, vitality, and freedom from illness and calamity.

- When cows plow the fields, it signifies the arrival of spring, symbolizing the abundance of life, vitality, and hope.

- Cows excel in farming and represent diligence, symbolizing bountiful harvests, abundant crops, and favorable weather conditions.

- In ancient mythology, there are numerous depictions of cows associated with wealth and prosperity, as they are seen as bringers of fortune and treasure. Cows symbolize auspiciousness, blessings, and prosperity.

- A bull market is highly desired in stock trading and financial commerce, so cows symbolize the development of bullish market trends and upward momentum in the securities market.

- “牛脾气” (niú píqì) refers to a stubborn and uncompromising temperament, requiring others to coax and placate in order to be forgiving. It represents a strong and stubborn temperament, often used to describe someone’s personality traits.

Introduction to Cow Culture

Cow is one of the important livestock and is regarded as the “chief of the six livestock” in China. China has a long history of Cow farming, and Cow have been closely associated with the lives of the working people. Chinese Cow culture is rich and diverse. This article introduces Chinese Cow culture from three aspects: the role of Cow, the historical development of Cow culture in Chinese traditional culture, and the Chinese Dream and the spirit of Cow. It aims to demonstrate the profound influence of Cow culture on the social life and cultural development of the Chinese people.

China is vast and abundant, with a history of five thousand years. The diligent and brave Chinese people have forged a profound and long-standing traditional culture, and the culture related to Cow is an important part of it. The deep friendship between humans and Cow and the great contributions of Cow to human social development can be seen in various literary works, visual arts, and other materials throughout different periods.

Since ancient times, China has been an agricultural society, and along with the development of agricultural culture, Cow culture has been continuously created and recorded in the long history of the Chinese nation. Cow are large and powerful, gentle and easy to tame, and have been good friends of humans since ancient times. Every spring, when all things revive, people lead Cow in agricultural production activities. From plowing fields to transporting goods, these silent Cow have undertaken numerous tasks and missions. Cow have helped the working people share a large amount of heavy production activities, so people have great respect and gratitude towards Cow. Therefore, throughout history, hardworking working people, knowledgeable experts and scholars, and talented literary figures have all sung praises for the dedication and selfless contributions of Cow. This continuous inheritance and innovation have made Chinese Cow culture shine brilliantly.

The Connection between Cow and Human Production Activities

Cow were the first animals domesticated by humans and were known as the “chief of the six livestock.” According to historical records, more than 7,000 years ago, during the Neolithic period, humans domesticated and utilized Cow for labor purposes. Cow have different types and roles. Dairy cows consume little but contribute greatly, symbolizing selfless dedication. The renowned writer Lu Xun has written many famous quotes and praises for the spirit of Cow’s dedication, such as “They eat grass and produce milk” and “With furrowed brows, they face the scorn of thousands, bowing their heads willingly like a child.” Oxen and water buffalo are strong and are often used in agricultural production, representing diligence. There are records in ancient times of using oxen to pull plows to till the land, and it was found that due to the large size and strength of Cow compared to other animals, using oxen to pull iron plows significantly increased production efficiency. The combination of Cow and iron tools marked a significant technological change in agricultural society. From then on, human agricultural production capacity made a qualitative leap, entering an era of meticulous farming and expanding living space, which laid a solid foundation for the development of human social civilization. During that time, Cow held the highest position in the hearts of the working people and were greatly respected. Poets and literati of ancient times composed numerous poems praising the hardworking nature of Cow, their selfless dedication, and their noble qualities of toiling without seeking rewards. These poems also expressed the respect and care of the working people towards Cow. In addition to their agricultural roles, Cow also hold great value in other aspects of human life. In terms of transportation, “Livestock husbandry research in the Song Dynasty” states that “Cow husbandry provides the force for transportation industry.” During the Song Dynasty, in times of war or social engineering construction, transportation resources were often scarce, and the government would requisition.

The origin of Cow and traditional Chinese culture

The worship of Cow in Chinese traditional culture can be traced back to 4,000 years ago during the period of Emperor Yu’s flood control. According to legend, whenever a flood was successfully controlled, iron cow statues were cast and placed in the water to calm the floods. Even before humans started using Cow for work during the Shang and Zhou dynasties, Cow held a significant position. They were commonly depicted on the noble bronze artifacts as prominent decorative motifs. At that time, the depictions of Cow were mostly abstract, focusing on distinctive characteristics such as curved horns, large ears, and round eyes. This can be seen in the ancient script of the word “牛” (niú), where a vertical line represents the face of the cow, two vertical lines with curves represent the horns, and two small strokes below represent the ears. Throughout the successive dynasties, scholars and literati have always enjoyed writing poems and painting Cow, resulting in numerous splendid works that have been passed down to this day.

For example, the poet Li Gang’s poem “The Ailing Ox” depicts the plight of an old ox that is sick and exhausted from plowing thousands of acres of land, highlighting its spirit of perseverance and dedication even in the face of physical weakness. The poem praises the ox for its selflessness and willingness to toil for the benefit of all beings, embodying its noble character and unwavering commitment. By using the ox as a metaphor for oneself, the poet conveys his own exhausted state while emphasizing his unwavering patriotism and love for the country.

The earliest surviving painting on paper featuring Cow is the “Five Oxen” by the Tang dynasty painter Han Huang, created around 1,300 years ago. In the painting, the five oxen are depicted with different postures and expressions, some lowering their heads, some raising them, some in motion, and some standing still. The artist’s meticulous observation and skillful technique give each ox a human-like emotional quality, showcasing their distinct character traits. The affection of scholars and literati towards Cow is evident in their works. In folk culture, there are also numerous cultural activities and art pieces related to Cow. Ethnic minority groups often organize various competitions involving their own Cow, and the lively bullfighting events held annually in villages of ethnic groups such as the Miao and Dong people are accompanied by singing and dancing to celebrate festivals, express good wishes, and convey the longing for a better life. During the celebration of Chinese New Year, families decorate their windows with beautiful paper-cuttings to welcome the new year. Many of these paper-cuttings feature Cow, reflecting the agricultural life of the laboring people and symbolizing their hard work, perseverance, and pursuit of a better life.

cow horns in Chinese culture

Cow horns, or cattle horns, symbolize auspiciousness and good fortune. As decorative ornaments, cow horn pendants serve as protective talismans, representing safety and smoothness. They also symbolize health and longevity, as cow horns are believed to alleviate fatigue and rejuvenate the spirit. Additionally, cow horns symbolize growing old together, and cow horn pendants can be exchanged as tokens of commitment between couples, representing a lifelong companionship.

In the folk culture of the Miao ethnic group, cow horns symbolize the triumph of good over evil and carry the meaning of extreme vitality, representing the dispelling of negative energy. When there are protruding beams above the bed, the household shrine, or the office desk, which may affect the luck of the family, placing or hanging cow horn decorations beneath the beam can bring peace of mind.

In the southeastern region of Guizhou, the Miao people deeply respect and worship water buffalo horns and silver accessories adorned with buffalo horns. Wearing broad silver buffalo horn ornaments on top of the head is considered beautiful and prestigious, representing the primal fusion of human and buffalo forms. Miao households proudly hang water buffalo horns on central pillars for worship, considering them a source of pride.

cow ears in Chinese culture

In ancient times, when feudal lords established alliances, they would cut off the ears of an ox and use them to seal the blood oath. The representative of the leading alliance state would hold a tray containing the severed ox ears, hence the term “holding the ox ears” to refer to the leading alliance state. Later, it came to broadly signify the most influential person in a certain aspect or the person holding a leadership position in a particular field.

Cow in Chinese mythology

The Chinese ethnic group has a long and rich history, giving rise to numerous myths and legends. As an integral part of Chinese history, the Cow also plays many significant roles in mythological tales. Here are the classic representations of the Cow:

Qing Niu (青牛):

Also known as “Banjiao Qing Niu,” it originates from the book “Shan Hai Jing” and is depicted as the mount of Taishang Laojun (the Grand Supreme Elderly Lord) in the novels “Fengshen Yanyi” and “Journey to the West.” It resembles a water buffalo and is entirely dark green. In “Journey to the West,” it initially appears as a demon in the mortal realm, creating obstacles for the four main characters of the story.

Kui Niu (奎牛):

The classic depiction comes from the novel “Fengshen Yanyi,” where it is the mount of Tongtian Jiao Zhu (the Primordial Supreme Master). Kui Niu is a jet-black water buffalo surrounded by auspicious lights and colorful clouds. Its horns resemble crescent moons, and in the middle of its forehead, there is a Taiji Bagua symbol. It brings storms and rain when entering or leaving the water and emits thunderous sounds while radiating a sun and moon-like glow.

Kui Niu (夔牛):

Originating from the book “Shan Hai Jing,” Kui Niu, also known as Lei Shou, is born on the Wave-Flowing Mountain in the Eastern Sea. It resembles an Cow, entirely gray, without long horns but with only one leg. Its roar is as thunderous as thunder itself. The most widely circulated myth is its involvement in the battle between the Yellow Emperor and Chi You, where it was slain by the Heavenly Queen of the Nine Heavens and turned into a drum, assisting the Yellow Emperor in defeating Chi You and unifying the world.

Wu Se Shen Niu (五色神牛):

The mount of Huang Feihu, the Divine Emperor of Mount Tai in “Fengshen Yanyi.” The Wu Se Shen Niu is said to be a divine steed with five-colored fur, boundless strength, and fearless of ferocious beasts. It can travel on clouds.

Old Cow in the Cowherd and Weaver Girl story:

In the tale of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl, the old Cow is not only a key character that enables the Cowherd to unite with the Weaver Girl but also sacrifices its own skin (in some versions, its horns) so that the Cowherd can catch up with his wife and children. It selflessly gives everything for the Cowherd and Weaver Girl’s reunion.

Niu Mo Wang (牛魔王):

A demon king from “Journey to the West,” known for his bold personality and formidable strength, surpassing even Sun Wukong in martial prowess. He not only possesses great personal power but also has a strong network of relationships. He is the ruler of Mount Cuifeng and Mount Jilei, the husband of Princess Iron Fan, the father of Red Boy, the blood brother of the Seven Great Sages, the friend of the Dragon King of the Western Sea and the Nine-Headed Bug, and the younger brother of the True Immortal of Divine Powers.

Niu Jin Niu (牛金牛):

According to later biographies, Niu Jin Niu is a star deity associated with the twenty-eight constellations, specifically the second constellation of the northern seven constellations. It is a god of wealth, affiliated with the metal element, governing the upper part of the ninth celestial stem and overseeing Mount Maoling. In popular mythology, it is associated with the Cowherd and Weaver Girl legend, later adopted as the constellation Taurus.

Liang Liang (軨軨):

Liang Liang resembles a water buffalo, but with tiger-like patterns on its body. It has a clear and melodious voice, gentle temperament, and appears harmless. However, it is actually a legendary disaster beast that possesses the power of natural calamities and can summon floods to submerge everything. Fortunately, it rarely leaves the Eastern Empty Mulberry Mountain and prefers to stay indoors for thousands of years.

Zi Tie (呲铁):

Also known as Nie Tie, Zi Tie is Cow-shaped, entirely black, with a pair of enormous horns that are indestructible by swords and blades. It enjoys eating raw iron ore and produces dung that is also unbreakable. Zi Tie is considered an extremely rare and ancient exotic beast, and its body is an extraordinary material for forging.

Fei (蜚):

Fei resembles an old Cow with a single eye and a white-colored head. Its tail is snake-like. It is the ancient god of calamity sealed in Mount Tai and is one of the four ancient calamities alongside Liang Liang. Similar to Liang Liang, it controls natural disasters, but while Liang Liang causes floods, Fei brings droughts. Legend has it that when it enters the water, it evaporates; when it walks through grass, plants wither; and as it travels through the human world, droughts and plagues occur, leaving a trail of devastation and annihilation.

Cow-Head (牛头):

Cow-Head, also known as the Cow-Headed Demon, has the head of an Cow and the body of a human. It is one of the Yama’s messengers in the underworld, responsible for traversing between the realms of the living and the dead, escorting souls to the afterlife. Although seemingly inferior and abundant in numbers, Cow-Head is, in fact, one of the oldest deities in the underworld, ranking as one of the ten Yama Generals and commanding an endless number of Cow-headed entities. Its combat prowess is extraordinarily powerful.

Qiong Qi (穷奇):

Qiong Qi resembles a tiger with a pair of wings and is also described as having an appearance similar to an Cow with hedgehog-like fur. It is a demonic deity born out of the world’s darkness and is one of the oldest and most malevolent beasts, classified as one of the four ancient calamities. It favors evil and detests good, subverting the balance of morality wherever it goes. The more wicked and bloody the actions, the more it favors and empowers individuals. Conversely, acts of kindness and justice easily enrage it.

cows in China History

Cow holds a significant position in the development of Chinese history and culture. They are one of the six livestock animals and have been the helper of farmers in plowing and cultivating fields. They were used as offerings in ancient large-scale rituals and are also one of the twelve zodiac animals and one of the twenty-eight constellations. The Chinese character for “cow” represents qualities such as endurance, perseverance, and tenacity, but it can also imply stubbornness and being stuck in one’s ways.

Research indicates that modern cows originated from the aurochs, an extinct large bovine species. Aurochs were sizable animals, slightly smaller than elephants, but they were fast and unyielding, even when confronted by fierce predators. However, the last aurochs died in 1627, marking the extinction of the species. A number of aurochs’ skeletal remains have been unearthed in central and northern regions of China, mostly from the late Pleistocene deposits, with a few discoveries dating back to the Western Zhou Dynasty and the Spring and Autumn Period.

From the untamed aurochs to the burden-bearing plowing Cow and the milk-producing and meat-producing cows, their transformation can be attributed to human domestication. Around 10,500 years ago, the civilizations of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers domesticated the common Cow. The Indus Valley Civilization domesticated humped Cow around 8,000 years ago. The Yangshao Culture in China also involved Cow husbandry, indicating that around 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, ancient Chinese civilizations were capable of domesticating Cow.

The yak, found on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is domesticated from the wild yak. Through whole-genome resequencing, researchers have determined that nomadic tribes on the plateau domesticated wild yaks around 7,300 years ago, and with the migration of these nomadic tribes, yaks gradually spread throughout the entire plateau.

Chinese civilization has been built upon agriculture, and our ancestors have always recognized the role of Cow in agricultural culture. Almost every dynasty had legislation prohibiting the consumption of beef to ensure an adequate number of working Cow. This led to the genetic focus of domestic Cow in China being geared towards draft animals. With the development of society, draft animals gradually transitioned from being production tools to temporary meat sources, resulting in their meat quality and growth rate being inferior to foreign breeds.

In the cultural sites of Hemudu and Luojiajiao, archaeologists discovered a large number of water buffalo remains, which opened up an extraordinary history: the domestication of cattle in ancient China.

Around 7,000 years ago, in the southeastern coastal and swampy regions of China, the ancestors of our primitive society began to domesticate wild water buffaloes. After 1,000 years of domestication, these wild water buffaloes gradually evolved into common cattle, becoming smaller in size and more docile, successfully responding to human commands.

During the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, the enslavement of cattle became more complex, and their uses gradually expanded. In that period of combined religious and royal authority, rulers often used cattle as sacrificial offerings to demonstrate the legitimacy of their rule. According to the Records of Rites (Li Ji), during the Western Zhou Dynasty, there were different levels of sacrificial cattle. Cattle used for sacrificing to heaven and earth had horns like chestnuts, those used for ancestral worship had horns like a closed fist, and the beef cattle used to entertain guests had broad horns that could reach a foot in length. In other words, the lower the horn development, the younger the cattle, and the higher their status in sacrificial rituals.

During the Zhou Dynasty, the Son of Heaven (the king) established the position of “Cattle Supervisor,” responsible for the sacrificial cattle. Sacrifices involving cattle were referred to as “tai lao” if they involved large numbers, and “shao lao” if they involved fewer, indicating a lack of high-quality offerings and thus being inauspicious. In oracle bone inscriptions, ancient people recorded different types of cattle. For example, the term “shen niu” in oracle bone inscriptions refers to water buffalo. One character in oracle bone inscriptions consists of a horizontal stroke below the “niu” character, reflecting the ancient practice of nose piercing on cattle that was prevalent since the Xia, Shang, and Zhou periods.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, there were increasingly diverse types of cattle, their functions, and methods of handling them. New breeds such as “jun,” “bei,” and “mao” cattle emerged. The record of “jun” cattle appears in the Book of Songs (Shi Jing), where it mentions “Who says you have no cattle? Ninety ‘jun’ cattle” – characterized by their yellow coat color and black lips, indicating their superior quality. Mao cattle were often used to make flags, weapon decorations, and adornments for clothing and hats. The Book of Xunzi (Xunzi) records the history of Central Plains people borrowing the technique of using yak tails from people of the Western Sea to make leather streamers. Records about “bei” cattle can be found in the Er Ya, which is actually referring to the currently popular Gaofeng cattle found in southern coastal regions and Hainan Island but rarely seen in the north. During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, people considered the meat of Mao cattle to be of the finest quality. The Lüshi Chunqiu (The Annals of Lü Buwei) states, “The most delicious meat is… the meat of Mao and elephant,” highlighting the deliciousness of Mao cattle meat.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, besides being consumed, cattle were often used as means of transportation and draft animals. The Jingtian system stipulated that every set of sixteen wells should have one warhorse and one ox for military use. People emulated the herdsman system from the Xia, Shang, and Zhou periods and appointed dedicated officials to manage working and draft cattle, and the use of whips to control the cattle also emerged. Furthermore, the ancient practice of nose piercing on cattle, which had been prevalent since the Xia, Shang, and Zhou periods, continued. The Zhuangzi (Zhuangzi) records, “To make it submit, tie up its nose like a horse’s head; to make it mad, pierce its nose like a cow’s,” illustrating the increasingly rough and violent treatment of cattle by ancient people, closely related to their use in plowing the land.

After the emergence of iron farming tools, large livestock like cattle gained favor among people. They discovered that cattle could sometimes be easily angered and required rough handling, so in the course of time, some regions began to use donkeys for farming, leading to further agricultural development. However, to distinguish between the quality of cattle, people summarized certain techniques for assessing cattle. During the Spring and Autumn period, Ning Qi, the chief minister of Duke Huan of Qi, compiled the “Xiang Niu Jing” (Classic of Ox Physiognomy). Later, the book came into the hands of Baili Xi from the state of Qin but eventually became lost, leaving only fragmentary phrases recorded in the later book “Qi Min Yao Shu” (Essential Techniques for the Welfare of the People).

Ancient China banned the killing of cow

In ancient China, killing cows was strictly prohibited. Cows held a high status in Chinese history, and it was forbidden for common people to casually slaughter working cattle. In the pre-Qin period, killing a cow could result in severe punishment. On one hand, this prohibition was due to the agricultural tradition in China, where cows played a crucial role as an important farming tool. The prohibition aimed to emphasize the importance of agriculture. On the other hand, it was also related to ancient Chinese sacrificial customs.

Before the Qin and Han dynasties, people attached great importance to worshipping the heavens. However, ordinary people did not have the privilege to conduct heavenly worship. Only the emperor had the authority to perform such rituals, and the main meat used in these ceremonies was beef. Therefore, during that time, professional butchers were allowed to dissect cows for the king’s rituals, but ordinary farmers were not allowed to kill cows. This tradition also led to the ritualistic significance of killing cows in some peasant uprisings.

Although the killing of working cattle was strictly prohibited, it didn’t mean that people didn’t consume beef in reality. Retired working cattle that were no longer able to work could be consumed after reporting to the authorities. With the development of productivity, cows ceased to be scarce animals, and beef consumption gradually became more common among the general population. Some emperors even contemplated whether to continue the prohibition on killing cows, but since many people were already consuming beef (even famous poets like Li Bai and Du Fu enjoyed it), it was practically impossible to enforce the ban. During the Yuan Dynasty, the ruling class was of nomadic origin and already consumed beef, further diminishing any restrictions on beef consumption.

Cows used in ancient china

“The Records of the Grand Historian” states, “Agriculture is the foundation of the country, and there is no greater priority.” Ancient China was built upon agriculture, with a focus on farming as the core. Cattle played a crucial role in ancient China as the primary draft animals. They were not only used for their meat and milk but also extensively utilized in agriculture, transportation, leather industry, weapon manufacturing, and medicinal purposes.

Pillar of Farming

Originally, the Han Chinese relied on manual labor using hand plows and hoes for farming. There are numerous records about the use of “lei” and “si” (types of plows) in ancient China, such as in the “Book of Rites,” which mentions, “The Son of Heaven personally operates the plow and the hoe,” and in the “Later Han Annals,” which describes, “Grasp the handle of the plow, hold the blade of the hoe.”

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, there was a significant social transformation, and the introduction of cattle plowing and iron farming tools greatly enhanced productivity, allowing for greater yields with less effort.

Ancient cattle plowing techniques continued to evolve. During the Warring States period, the plow could only break the soil, but by the Han dynasty, a plowshare was added, enabling the turning of soil clumps. During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, cattle plowing was further promoted, and a short yoke plow that could be pulled by a single ox was introduced during the Eastern Han period. This leap in cattle plowing efficiency marked a significant advancement.

As a result, agricultural techniques became more advanced, versatile, and adaptable to various types of land, greatly boosting ancient agricultural production and improving crop quality.

Cattle were invaluable helpers in agricultural production, as evidenced by records of “iron plows and ox plowing” during the Spring and Autumn period. In the early years of Emperor Wu of Han’s reign, only wealthy households had the means for cattle plowing, while farmers primarily used iron or wooden tools. Zhao Guo, an agriculturalist during Emperor Wu’s reign, summarized the experience of cattle farming and promoted techniques such as coupling plows and alternate-field farming. The government also facilitated the leasing of plowing cattle, which alleviated the burden on farmers to some extent and increased agricultural output. During the Han and Eastern Han periods, cattle plowing technology gradually spread in the northern and southern regions. Areas such as Jing, Yang, and Liang in southern China, where cattle plowing was previously uncommon, experienced significant progress in local productivity and stimulated socioeconomic prosperity.

During the Han dynasty, cattle culture became further integrated into agricultural production. On the day of Lichun (the beginning of spring), local governments organized the stacking of soil into the shape of oxen outside city gates to encourage farming, symbolizing the start of spring plowing. As recorded in the “Later Han Annals: Records of Rites and Ceremonies,” “On the day of Lichun, before the end of the fifth watch of the night, officials in the capital, as well as officials from counties and prefectures, down to food measuring officers, all wore blue garments and raised blue flags. They arranged soil oxen and plowmen outside the gates, indicating auspicious farming, until the day of Lixia (beginning of summer).”

Zhuge Liang’s Clever Creation: Wooden Oxen and Flowing Horses (Transportation Tool)

During the Three Kingdoms period, there are records in both official historical accounts and classical novels about Zhuge Liang’s creation of wooden oxen and flowing horses. In “Records of the Three Kingdoms: Biography of Zhuge Liang,” it is mentioned, “Liang’s nature excelled in ingenious ideas, and he developed the continuous crossbow and wooden oxen and flowing horses according to his own designs.” In “Book of Southern Qi: Biography of Zu Chongzhi,” it is stated, “Zhuge Liang had wooden oxen and flowing horses, and he made a device that could move on its own without relying on wind or water, without requiring human labor.” There are also references to “wooden oxen and flowing horses” in “Biography of Emperor Houzhu” and “Biography of Shu” in “Records of the Three Kingdoms.” From the official historical records, it is indeed true that Zhuge Liang created wooden oxen and flowing horses. However, the specific details of their construction are not mentioned in the historical accounts.

In the classical novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” in the 102nd chapter, it is mentioned that Zhuge Liang sent over a thousand craftsmen to Hulugu Valley to build wooden oxen and flowing horses in order to capture the strategist Sima Yi. These wooden oxen and flowing horses could travel alone for dozens of miles or in groups for thirty miles. They could transport grain day and night without needing to eat.

When Sima Yi heard that the Shu army used wooden oxen and flowing horses for transporting supplies, he sent troops to seize some of them and had the craftsmen dismantle them to replicate their dimensions and make over two thousand more. However, Sima Yi did not know that the tongue of the wooden oxen and flowing horses made by Zhuge Liang contained a mechanism. Later, in a major battle between the two armies, Wang Ping followed Zhuge Liang’s instructions and turned the tongues of the wooden oxen and flowing horses, causing them all to stop moving. Ultimately, Sima Yi’s Wei army was defeated.

These wooden oxen required no external power source and exhibited excellent maneuverability. In cultural interpretations, the combination of wooden oxen and flowing horses is considered legendary and remarkable.

Battle Weapon

In addition to their use as tools for farming and transportation, cattle also played a significant role on ancient battlefields. During the Warring States period, the Qi general Tian Dan cleverly used the fire oxen formation to defeat the Yan army.

Taking advantage of the cover of night, Tian Dan gathered thousands of cattle and attached sharp blades to their horns. He tied reeds soaked in oil to their tails, set them on fire, and led a charge with five thousand brave warriors following the cattle. The Yan army was frightened and defeated.

The fire oxen formation refers to the tactics invented by Tian Dan of the State of Qi during the Warring States period. Tian Dan, a distant relative of the Qi king, was elected as a general after the death of the city’s defender. Under Tian Dan’s leadership, the morale of the city’s defenders was rejuvenated.

In 279 BC, King Hui of Yan ascended the throne. He had always been at odds with General Yue Yi. General Yue Yi had besieged the city of Jimo for three years but failed to capture it. Tian Dan used a stratagem to have King Hui replace General Yue Yi with cavalry.

Tian Dan selected over a thousand cattle and adorned them with red silk and colorful patterns. He tied sharp knives to their horns and soaked the reeds attached to their tails in oil. Tian Dan ordered the destruction of several sections of the city walls and drove the cattle outside the city at night, with five thousand warriors following closely behind. When the reeds were set on fire, the frightened cattle ran towards the Yan army, and the five thousand Qi warriors attacked the Yan army. The people in the city struck copper objects, creating a deafening noise. The Yan army was greatly alarmed and defeated, fleeing the battlefield.

The fire oxen formation helped the Qi army turn the tide of battle, transforming defense into offense. They pursued the retreating Yan army, and the local officials, soldiers, and civilians of the Qi territory that had been occupied by Yan responded to the resistance and welcomed Tian Dan’s arrival. In just a few months, Qi recovered more than seventy cities that had been occupied by enemy states.

Tian Dan, in the face of national crisis, employed ingenious tactics to stabilize the collapsing situation, allowing the people of Qi to gradually believe that their country would not perish. This boosted the morale of the people, and the cattle became famous through their participation in battles.

Similarly, during the Eastern Han Dynasty, Emperor Guangwu Liu Xiu also rode on cattle to wage war on the battlefield. “Book of Later Han” records that “at the beginning of Guangwu’s uprising, he rode on cattle and only obtained a horse after killing a county magistrate in Xinye.” At the start of Liu Xiu’s uprising, he had little wealth, a small number of troops, and extremely humble equipment. As the leader of the rebel army, Liu Xiu couldn’t even afford horses. In battle, he used a yellow ox as his mount, exuding a formidable presence.

Later, after capturing Xinye County and seizing enemy horses, Liu Xiu finally acquired horses to ride. Despite the lack of superior horses and weapons, Liu Xiu relied on his courage, intelligence, and strategic abilities. He gathered talented individuals and confronted various forces, eventually establishing the Eastern Han Dynasty and ushering in a period of revitalization under the reign of Emperor Guangwu.

It can be seen that countless heroes have written songs of victory on the battlefield with the help of cattle. Cattle have witnessed numerous historic moments of emperors, kings, and generals’ rise and fall, making them truly special.

Water Buffalo in Feng Shui

According to “Zaohua Quanyu,” it states, “Qian (Heaven) is represented by horses, and Kun (Earth) is represented by cattle, so horses have round hooves, while cattle have split hooves.” In ancient China, horses symbolized the yang energy of Qian, while cattle symbolized the yin energy of Kun. When a horse is sick, it lies down, indicating that yin energy has overcome yang energy. On the other hand, when a buffalo is sick, it stands up, indicating that yang energy has overcome yin energy. When a horse stands up, it extends its front legs first, and when lying down, it extends its hind legs first, following the Qian yang energy. Conversely, when a buffalo stands up, it extends its hind legs first, and when lying down, it extends its front legs first, following the Kun yin energy. That is why horse hooves are round-shaped, while buffalo hooves are split-shaped.

Cattle represent the Kun yin energy, which corresponds to the element of earth in the Five Elements theory, and earth has the ability to control water. According to folk legends, the dragon that caused floods was “afraid of iron.” Therefore, in ancient China, people cast iron buffalo as water suppressors. According to the “Revised Anhui Tongzhi” (version from the Guangxu period), during the Han Dynasty, the region of Anhui had an official position called “Iron Official” who “cast iron buffalo to suppress this area. The local history book records that there were many water monsters in Jianghu, and when the city was first built, iron buffalo was used to suppress them.” Due to frequent floods at that time, in order to subdue water monsters, the local government cast five iron buffaloes and placed them in different locations within the city. The iron buffaloes were buried in the ground with their backs slightly exposed. Some people even claimed to have heard the iron buffaloes breathe, which amazed the people and referred to them as the “Great General Iron Buffalo.”

Over time, water buffalo suppressors were not necessarily buried in the ground but were also placed on embankments. There is still a bronze buffalo statue in Kunming Lake in the Summer Palace in Beijing. It was cast in the 20th year of the Qianlong reign (1755) and bears a four-character inscription written by Emperor Qianlong himself.

Sacrifice

Sacrifice was one of the important activities in the political life of ancient people, and cattle were the most noble sacrificial offering. The annotation in the “Shuowen Jiezi” states: “牛 (niú), a large sacrificial animal.” “牲” refers to a whole cow used for sacrifice. The concept of using cattle as the highest standard for sacrifice was shared in Han Dynasty society. “Baihu Tongyi” records: “In the five sacrifices, the emperor and feudal lords offer cattle, while ministers and high-ranking officials offer sheep, following the seasonal sacrificial animals.” In the Han Dynasty, only the emperor could use a whole cow for sacrifices, and there were strict procedural regulations. Common people were not allowed to slaughter cows for sacrifices. “Instructions were given to the people, stating that they were not allowed to have sacrificial activities outside their homes. Those who violated this order would be punished, and anyone who slaughtered cattle without authorization would be subjected to penalties.” The use of cattle to emphasize the hierarchical concept of the ruling class elevated the symbolic significance of cattle in politics.

Bullfighting

During the prosperous economic period of the Han Dynasty, with a wide variety and large number of cattle, bullfighting emerged in rural areas and was greatly loved by the masses. In their leisure time amidst agricultural busy seasons, people enjoyed bull-versus-human or bull-versus-bull fights, satisfying their spiritual needs for self-recreation. Bullfighting activities appeared in northern China during the Han Dynasty, and the discovery of bullfighting scenes in places like Nanyang indicates the popularity of this entertainment activity at that time.

Bullfighting is still practiced in China today, mainly concentrated in regions such as Jinhua in Zhejiang Province and among ethnic minority groups in the Qiandongnan area of Guizhou. It is an entertainment activity rich in ethnic flavor.

Chinese Cow god

In China, cattle symbolize agriculture and are even considered agricultural deities. The legendary figure of Shen Nong, an ancient inventor of various agricultural tools and farming techniques, is depicted with a human body and a bull’s head, known as “牛首人身” (niú shǒu rén shēn).

The direct worship of the bull deity began during the Spring and Autumn period. According to historical records, people in the state of Qin considered cattle as spirits of trees and established shrines to worship them, known as “怒特祠” (nù tè cí). Scholars believe that these “怒特祠” were the origin of later bull temples found throughout the country. During the military campaign of King Huiwen of Qin (the great-great-grandfather of Qin Shi Huang) against the state of Shu, the Shu region was difficult to breach due to natural barriers. King Huiwen employed a tactic similar to the Trojan horse, but instead of a wooden horse, he used stone bulls.

In the “Stone Bull Strategy,” King Huiwen falsely claimed to possess stone bulls capable of excreting gold and deceived the greedy king of Shu to open up a road for the transportation of the stone bulls to Qin. However, this action paved the way for the Qin army’s invasion instead. Later, this road became an important route connecting the Shu region with the Central Plains and came to be known as the “Golden Bull Road” (金牛道).

While the common people were not concerned with court disputes, the tradition of worshipping the bull deity was passed down through generations. Some scholars believe that the reverence for the bull deity already existed in the Shu region before its annexation by Qin. After Qin conquered Ba and Shu, Li Bing, the chief engineer responsible for constructing the Dujiangyan irrigation system in Chengdu Plain, transformed into the deity “Cangniu” (苍牛), defeating the river deity and bringing prosperity to the people. This deep-rooted worship of the bull deity among the ancestors of the Shu kingdom is evident.

After the Han Dynasty, with the revival of Confucianism and the widespread popularity of the theory of “harmony between heaven and humans” among the common people, Confucian ethics gradually became deified. Even Confucius’ disciple, Ran Geng (styled Bonyu), was mistakenly revered as the Bull King among the populace, and the worship of the Bull King gradually spread nationwide. Various regions started celebrating the Bull King’s birth (in the lunar months of June or August) with activities known as “牛王会” (Niu Wang Hui), meaning the Bull King Assembly. However, the most flourishing worship of the bull deity was in the southwestern region, particularly in Sichuan. The Niu Wang Festival in Sichuan is celebrated on the first day of the lunar month of October, to ensure it does not interfere with agricultural activities.

According to historical records from the Ming and Qing dynasties, customs celebrating the Bull King Festival and worshiping the bull deity were observed in Anhui, Jiangxi, Guizhou, Guangdong, and Sichuan, with the Min River basin in Sichuan as the central hub. The main activities of the celebration included making sticky rice cakes, sticking them to the bull’s horns, and laboring over the bull’s hardships. It was believed that if the sticky rice cakes were not attached to the bull’s horns, the bull would shed tears. On that day, the plowing oxen were given a break and leisurely led around by farmers. Farmers would also bring the oxen to the water’s edge, allowing them to see their own reflection in the water, as it was believed that the oxen would be delighted to see the grains stuck on their horns. Additionally, various puppet shows were performed to entertain the bull deity.

The indigenous cultures of ethnic minority groups in the southwestern region have preserved more of their ancestral traditions and have richer reverence for the bull deity. For example, the Zhuang ethnic group in Guangxi celebrates the Bull Soul Festival in early April, granting a day off for the working oxen and summoning their spirits. The Dong ethnic group in Guizhou has the Niu Washing Festival in early June, where farmers lead their oxen into the river to bathe them and wish them safety. The Buyi ethnic group in Guizhou celebrates the Bull Deity Festival, also in early April, during which the plowing oxen not only rest but also partake in tasting the black rice offered to them. The Miao and Gelao ethnic groups hold their Bull King Festival on the same day as in Sichuan, the first day of October, with similar activities such as making sticky rice cakes and preparing sumptuous meals for the bull’s birthday. The Gelao ethnic group has a long-standing tradition of considering the plowing oxen as family benefactors, saying, “With a bull from the Gelao family, our lives are secured.”

The most famous Bull King Temple in Chengdu city was built during the Qing Dynasty, when the Bull King Festival was at its peak. In the seventh year of the Kangxi reign (1668), an outbreak of bovine plague occurred in the rural areas of Chengdu. Zhang De, the governor of Sichuan, took the lead in donating funds and established the Bull King Temple on East Street in Chengdu’s commercial center. An iron bull statue was enshrined in the temple, and the street in front of the temple came to be known as “Bull King Temple Street.” During the early 20th century, amid the warlord conflicts, the iron bull in the temple was removed. In the new century, as part of the urban redevelopment of old Chengdu, the Bull King Temple was also demolished. However, it was later rebuilt in a different location in San Sheng Township in the eastern suburbs of Chengdu.

Cow in yin and yang

In the concept of yin and yang, the cow can be associated with various symbolic meanings. Yin and yang represent the duality and complementary nature of all things in the universe. The cow, or ox, can be seen as a representation of yin and yang in different aspects:

Strength and Gentleness: The cow is often associated with strength and power, representing the yang aspect. However, it also embodies gentleness, patience, and nurturing qualities, which align with the yin aspect. The contrasting qualities of strength and gentleness coexist within the symbolism of the cow.

Hard Work and Relaxation: Cattle are known for their hard work in agricultural labor, representing the diligent and industrious yang aspect. On the other hand, they also exhibit a calm and relaxed demeanor, emphasizing the yin aspect of rest and rejuvenation.

Groundedness and Stability: Cows are grounded animals, firmly rooted to the earth. This symbolizes stability, reliability, and the yang aspect. Their presence evokes a sense of steadiness and balance, which aligns with the yin-yang concept.

Harmony and Balance: The cow’s representation in yin and yang signifies the harmonious integration of contrasting forces. Just as yin and yang find equilibrium and interdependence, the cow embodies the balance between opposing qualities, fostering a sense of harmony.

Overall, the cow’s symbolism in the yin-yang concept reflects the interplay between contrasting aspects and the harmony that arises from their integration. It serves as a reminder of the complementary nature of existence and the need for balance in all aspects of life.

Cow in feng shui

Office Placement of Cow

Taboos for placing a cow:

Avoid wooden materials.

A cow made of gold emits a golden glow, symbolizing prosperity and wealth in work and business endeavors. If the cow is made of copper, it can be gold-plated to radiate a sparkling brilliance. Ceramic material can also be used, but careful consideration is needed for the placement. Avoid using a cow made of wood because, according to the Five Elements theory, the zodiac sign “Chou” belongs to the Earth element, and wood restricts the Earth element, hindering the manifestation of its dynamic power.

Prefer a reclining posture.

Choose a cow with a reclining posture, as it represents tranquility and peacefulness. Other postures are not suitable.

Optimal placement in the northeast, slightly north.

As the zodiac sign “Chou” belongs to the northeast, it is favorable to place the cow in that direction. Additionally, according to the theory of the three harmonies (“Si You Chou”), the “Si” and “You” directions are also good choices. However, avoid placing the cow in the southwest, slightly south (the zodiac sign “Wei”), as it conflicts with “Chou.” Therefore, individuals born in the Year of the Goat should also avoid using a cow as a placement. As for the quantity, it is not necessary to have many; one cow with significant dynamic power is sufficient.

Place it on the ground.

The cow should be placed on the ground to counteract any negative influence and dispel any unfavorable energy.

Avoid placing it in the bedroom.

As the zodiac sign “Chou” belongs to the Earth element, it is generally placed in the living room or central hall, facing west. Avoid placing it in the bedroom.

The cow is a common ornament, symbolizing prosperity and steadfastness, and can promote work and career development. However, when placing the cow, it is important to be aware of the taboos.

The Roles of the Cow

Symbol of Auspiciousness:

The cow is associated with strength and is often used as a symbol of strength, wealth, and power in sports clubs or competitions, both in Chinese and Western cultures.

Boosts Financial Fortune:

The cow is believed to enhance wealth luck, particularly in speculative investments. It is considered a powerful item for individuals engaged in stock trading, real estate, finance, banking, and other financial activities.

Supports Career Growth:

The cow is associated with authority and prosperity, projecting a sense of decisiveness and assisting in career advancement. It is suitable for those who are striving for success and aspiring to achieve their goals.

Attracts Wealth and Abundance:

The cow’s symbolism primarily focuses on enhancing financial fortune and business success. It exudes an aura of dominance and tenacity, benefiting individuals engaged in entrepreneurial pursuits and those whose destiny is aligned with the Earth element, which represents wealth.

Dispels Negative Energies:

With its strong and stable presence, the cow is believed to ward off evil and dispel various forms of negative energy. It serves as a protective talisman, especially for businesspeople and those in the early stages of their careers.

Brings Good Fortune:

Placing a cow in a shop or office can bring good luck, attract wealth and customers, and contribute to the flourishing of business. When placed in a personal space, it brings harmony and good fortune, attracting abundant wealth.

Symbol of Perseverance:

In Chinese culture, the cow symbolizes diligence and hard work. Throughout thousands of years, cows have been utilized as tools for farming, representing diligence, hard work, and strength. The cow embodies a sense of grandeur and resilience, often associated with expressions such as “bullish” and “unyielding spirit.”

These are the various aspects and roles of office placement and the significance of the cow. Cow figurines symbolize auspiciousness, contribute to career growth, and attract wealth and abundance. They are highly effective ornaments. However, it is essential to consider the placement techniques when placing a cow in an office.

Cow in Buddhism

In Buddhism, the cow represents noble dignity and virtuous conduct. Among the eighty auspicious characteristics of the Buddha’s physical form, one is described as “walking calmly and peacefully, just like the king of oxen.” In various epithets of the Buddha, he is praised as the “bull among humans” due to his boundless virtues. In Zen Buddhism, the cow is often used as a metaphor for the mind of sentient beings, as depicted in the “Ten Ox-Herding Pictures.” In the Lotus Sutra, the ox cart is used as a metaphor for the vehicle of Bodhisattvas, while the great white ox cart symbolizes the exclusive vehicle of the Buddha, referring to the profound teachings of Mahayana Buddhism.

In ancient India, where Buddhism originated, cows were considered sacred animals due to their customs and were revered as exemplars of character traits valued by Buddhist practitioners. As a result, cows were treated with great care and respect.

In Chinese folk culture, cows are also highly respected, and there is a title known as the “Yellow-Haired Bodhisattva.”

According to the Qingyi Lu, it is recorded: “The old farmer does not like to slaughter cows, saying that all the food and resources used by people in the world originate from the body of this Yellow-Haired Bodhisattva.”

Apart from these examples, there are numerous other metaphorical references to cows in various Buddhist contexts. For instance, in the Lotus Sutra, the term “ox cart” is used to symbolize the vehicle of Bodhisattvas, while the term “great white ox cart” represents the Buddha’s vehicle, which refers to the profound teachings of Mahayana Buddhism. In Zen Buddhism, cows are used as a metaphor for the mind of sentient beings, as depicted in the well-known “Ten Ox-Herding Pictures,” which represent the ten stages of practice.

Cow in Taoism

Cows have an intriguing connection with Taoism, and in television and film, Taoist priests are often referred to as “nose-ring old Taoists.” The Daoist scripture “Haiqiong Baizhenren Yulu” records: “In the past, the Xue True Person from Piling explored the great matter with the Chan School, and then had his nostrils pierced by the Xinglin True Person. This is called Qianxu not revealing a single truth.” In Daoism, the True Person Bidaoguang was pierced in the nostrils by his master, the Xinglin True Person Shitai, which metaphorically signifies Shitai imparting the essential teachings of cultivating inner alchemy and the Golden Elixir to Bidaoguang. Daoism uses the metaphor of controlling a cow’s actions by holding its nose to symbolize practitioners achieving the purpose of spiritual cultivation by controlling their own breath.

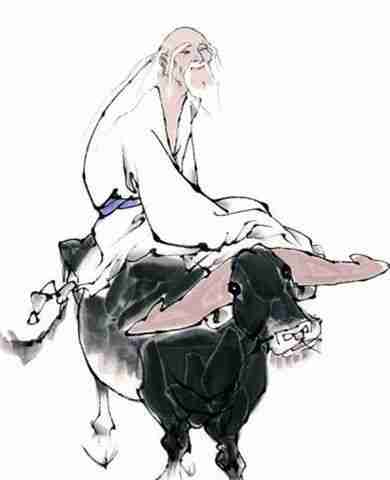

Another well-known story is that of Laozi riding a green cow through the Hangu Pass. Laozi is revered as the ancestor of Daoism and is considered the 18th incarnation of the Supreme Old Lord, the revered deity in Daoism. In the story, the gatekeeper of the Hangu Pass, Yin Xixian, built a thatched hut in Zhongnan Mountain and would climb the hut daily to observe the stars and divine the future. One day, Yin Xixian noticed a purple aura approaching from the east, which turned out to be Laozi riding a green cow. Yin Xixian invited Laozi to Zhongnan Mountain, where Laozi imparted his teachings, including the method of cultivating the Elixir of Life through breath control. Laozi also left behind the classic scripture “Wu Qian Yan” or “The Five Thousand Words.” “The Five Thousand Words” refers to the “Dao De Jing,” which is considered a sacred scripture in Daoism and serves as the foundation of Daoist teachings. When Laozi attained enlightenment and ascended to the realm of immortals, his mount, the green cow, also became a spiritual beast in the immortal realm.

Cow in Chinese Medicine

Niu Huang

One of the most well-known cow-derived substances in Traditional Chinese Medicine is “niu huang” (牛黄). Niu huang is a type of stone or calculus found in the gallbladder, bile duct, or liver duct of cattle, such as yellow cattle or water buffalo. It is considered a precious medicinal material with various therapeutic properties. Niu huang is bitter and slightly sweet in taste and has a cooling nature. It is believed to clear the mind, resolve phlegm, promote bile flow, and calm convulsions. It is used in the treatment of conditions such as fever-induced delirium, incoherent speech, infantile convulsions, and oral ulcers. Medicinal formulations like Angong Niu Huang Wan and Niu Huang Qing Xin Wan, which contain niu huang, are still used today and have shown excellent therapeutic effects.

Water Buffalo Horn

Water buffalo horn, derived from the body of cattle, is another medicinal substance used in Traditional Chinese Medicine. It has a bitter and salty taste and a cooling nature. Water buffalo horn is known for its ability to clear heat, cool the blood, and treat conditions such as headache due to heat, high fever with delirium, skin rashes, nosebleeds, infantile convulsions, and throat swelling. Additionally, due to its similar composition to rhinoceros horn, water buffalo horn has been used as a substitute for the latter.

Cow Horn (Bone Marrow)

Cow horn, specifically the dried marrow inside the horns of yellow cattle or water buffalo, is believed to have the ability to invigorate blood circulation and stop bleeding. It is used in the treatment of conditions such as purpura, excessive uterine bleeding, and bloody stools. In ancient times, cow horn was commonly employed for treating intractable postpartum dysentery.

Cow Bile

Cow bile possesses properties such as clearing the liver, improving eyesight, detoxification, and reducing swelling. It is primarily used in the treatment of eye diseases caused by wind-heat and jaundice. Cow bile is an important auxiliary material in the processing of certain medicinal herbs, such as the Southern Starwort (Chuan Bei Mu) and Coptis Rhizome (Huang Lian). For instance, when Southern Starwort is processed with cow bile, it is known as “Dan Nan Xing.” The processing reduces its drying and fierce properties, transforming its taste to bitter and cooling. It is then used for clearing heat, resolving phlegm, suppressing cough, treating stroke-induced phlegm obstruction, convulsions, and other related conditions.

Gelatin from Cow Skin

Gelatin from cow skin, known as “huang ming jiao,” is a type of gelatinous medicinal material produced by stewing yellow cattle skin. It is known for its nourishing yin, moistening dryness, hemostatic, and anti-inflammatory properties. Huang ming jiao is used in the treatment of conditions such as consumptive lung disorders, cough with blood-tinged sputum, hemoptysis, excessive menstrual bleeding, and traumatic injuries.

In addition to these tangible medicinal substances, various cow parts such as beef, cow bones, tendons, blood, hooves, and hoof capsules are also used in folk medicine. The contributions of cows in the development of Traditional Chinese Medicine should not be underestimated.

Cow in 12 Chinese zodiac

In the Chinese zodiac, the Cow (or Ox) is one of the twelve animal signs. It represents certain years in the lunar calendar and is associated with specific characteristics and personality traits. Here is some information about the Cow in the Chinese zodiac:

Years: The Cow is associated with the following years: 1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, 2009, 2021, etc. The Chinese zodiac follows a 12-year cycle.

Personality Traits: Individuals born in the Year of the Cow are believed to possess traits such as diligence, determination, patience, and reliability. They are known for their hard work, practicality, and methodical approach to life. They are considered trustworthy, responsible, and dependable individuals.

Compatibility: In terms of compatibility with other zodiac signs, Cows are believed to get along well with the Rat, Snake, and Rooster. They may have a harmonious relationship with these signs, as they share similar values and work ethics. However, they may face challenges in relationships with the Sheep/Goat, Horse, and Dog.

Career and Success: Cows are often associated with success in careers that require diligence, discipline, and perseverance. They are reliable workers who excel in professions such as farming, engineering, banking, politics, and medicine. Their methodical and patient nature helps them achieve their goals steadily.

Characteristics: Cows are known for their strong sense of responsibility, practicality, and loyalty. They approach tasks with thoroughness and attention to detail. They are not impulsive but prefer to analyze situations carefully before making decisions. Cows are also known for their calm and peaceful demeanor.

It’s important to note that individual personalities may vary based on factors such as upbringing, cultural influences, and personal experiences. The Chinese zodiac provides a general framework for understanding personality traits associated with specific animal signs, but it should not be considered the sole determinant of one’s character.

Cow and dragon

In various cultural and mythological contexts, the cow and the dragon are often seen as contrasting symbols with different connotations. Here are some perspectives on the relationship between cows and dragons in different cultural contexts:

Chinese Mythology: In Chinese mythology, dragons are revered as auspicious and benevolent creatures associated with power, wisdom, and good fortune. They are considered the symbol of imperial authority and are associated with the emperor. In contrast, cows are seen as gentle and humble animals that symbolize diligence, hard work, and prosperity. They are often associated with agricultural abundance and represent the importance of a peaceful and harmonious life.

Dragon’s characteristics and features: Dragon horns resemble deer, head resembles a camel, eyes resemble a rabbit, neck resembles a snake, belly resembles a mirage, scales resemble fish, claws resemble eagles, paws resemble tigers, and ears resemble cows. It embodies the serenity and gentleness of a deer, the perseverance of a camel, the agility of a rabbit, the cunning and hidden nature of a snake, the mystery of a mirage, the wealth of a fish, the survival instinct and accurate grasp of opportunities like an eagle, the majesty, independence, and vitality of a tiger, and the loyalty of a cow.

cow in Chinese ethnic groups

Regarding the worship of cows and cow-related mythologies in various cultures:

- In the ancient Chinese classic “Shan Hai Jing” (Classic of Mountains and Seas), there are depictions of deities with human faces and cow bodies.

- Many ethnic groups, such as the Miao and Buyi, have practiced cow worship.

In both Chinese and foreign mythologies, cows frequently play significant roles. In Han Chinese legends, it is believed that mice first gnawed open the sky during the primordial chaos, and cows separated the earth from the heavens, paving the way for the emergence of humans and all things. Creation myths involving divine cows are also found among the Naxi, Tajik, Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Sala, and Hani ethnic groups.

In Chinese folklore, the well-known story of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, also known as the “Cow and Weaver Love Story,” features an indispensable role played by an old cow. Another folk story states that cows were originally divine generals in front of the Jade Emperor’s palace, but due to a stumble at the Southern Heavenly Gate, they mistakenly interpreted the emperor’s orders as “sow three handfuls of grass seeds with each step” instead of “sow one handful of grass seeds with every three steps.” As a result, the fields became overgrown with weeds, and the cows were punished to eat grass on Earth and help farmers with their agricultural labor. The cows, being diligent and selfless, earned the respect of the people.

The worship of cows is observed in many ethnic minorities in China. The Cow Soul Festival, also known as Cow’s Birthday, Cow King Festival, Yoke Liberation Festival, or Kaiyang Festival, is a traditional festival celebrated by the Zhuang, Han, Yao, Dong, Li, She, and Gelao ethnic groups.

Zhuang Ethnic Group’s Cow Soul Festival:

The Zhuang ethnic group celebrates the Cow Soul Festival on the 8th day of the fourth lunar month in the northern part of Guangxi. During this festival, people stop plowing, and cows are freed from their yokes. The hosts feed the cows with homemade sweet wine and colorful sticky rice made with plant juices. On this day, the cowshed is cleaned, and the cows are bathed while drums are played to liven the atmosphere. It is strictly forbidden to harm or beat the cows on this day, as it may startle the cow souls and bring great misfortune to farming. At noon, each family holds a ritual to pay respects to the cows. The whole family sits around a table filled with a feast, and the head of the household leads the cow around the table while singing songs of respect. The cows are fed the five-colored rice. Finally, the family members stand up to touch the cows’ backs, expressing their blessings.

Li Ethnic Group’s Cow Festival:

The Li ethnic group in Hainan celebrates the Cow Festival in the seventh or tenth lunar month. The festival is presided over by the village leader. The festivities begin with the village leader beating gongs and drums to call the cow souls. The Li people believe that each cow has a beautiful cow soul stone. Many people keep these stones at home, and possessing multiple cow soul stones is seen as a sign of wealth. On the day of the Cow Festival, the village leader and his wife wash the cow soul stones with their homemade wine, offering the cows “blessing wine” by feeding them rice wine.

cow in Chinese new year

- Eating beef during the Chinese New Year symbolizes the soaring spirit of the ox.

- The symbolic meaning of the soaring spirit of the ox represents a prosperous career and continuous growth in the new year. Therefore, eating beef during the Chinese New Year carries a particularly auspicious meaning. Although the realization of this auspiciousness requires our own efforts, such symbolism can enhance our joy and happiness.

“Beating the Spring Ox” during the beginning of spring (立春) carries the meaning of “promoting farming” and embodies people’s simple aspirations for a year of good weather and abundant harvests. Beating the Spring Ox, also known as whipping the spring ox or whipping the earth ox, has its origins dating back to the Tang and Song dynasties and was prevalent during that time. Different regions have their own characteristics when welcoming the Spring Ox. During the ritual, people bow to the Spring Ox in sequence. After the ceremony, the crowd rushes forward, breaking the Spring Ox and snatching the soil of the Spring Ox to bring home and scatter in their cattle pens. From this, it can be seen that whipping the Spring Ox is a kind of breeding ritual, as scattering the soil from the Spring Ox promotes cattle reproduction.

Beating the Spring Ox is primarily a custom among the Han people in the Central Plains region of China, as well as among the Dong ethnic group. “Naochunniu” (闹春牛) is one of the most playful and humorous entertainment activities in Dong areas, combining simulated actions of various agricultural labor processes with the villagers’ recreational activities during their labor. It includes simulating actions such as plowing fields, harrowing, transplanting and cultivating seedlings, threshing grain, and carrying sheaves. There are also women carrying children to catch shrimp, fish, play with water, sing mountain songs, perform duets, and dance with leaves. All the female performers are dressed and adorned by men, performing hilarious and comical actions that are truly amusing.

Please note that the above translations are provided for reference and may not capture the full cultural nuances and historical context associated with these customs and traditions.

Cow day

The fifth day of the first lunar month, also known as “Niu Ri,” is the day in Chinese folklore when Nüwa created cattle. In all directions, there are gods of wealth. The fifth day of the first lunar month is commonly referred to as “Po Wu” (Breaking the Fifth). It is believed in Chinese folklore that all the taboos from the first to the fourth day of the lunar month can be broken on this day. According to old customs, people used to eat “water dumplings” for five days, which is called “Zhuo Bao Bao” in the northern regions. Nowadays, some families only eat them for three or two days, while others eat them every other day, but no one abstains from eating them. This tradition is observed from noble households to small households in the streets and lanes, and even when receiving guests. Women no longer follow any taboos and start visiting each other to exchange New Year greetings and congratulations. Newly married women return to their natal homes on this day. In some places, it is believed that it is inauspicious to engage in any activities on the fifth day, as it may lead to failures and setbacks throughout the year. The customs on the fifth day of the lunar month, in addition to the mentioned taboos, mainly involve sending away poverty, welcoming the god of wealth, opening markets for trade, and embody the Chinese people’s aspirations for warding off disasters, seeking good fortune, and prosperity.

In southern China, people worship the god of wealth on the fifth day of the first lunar month. According to Chinese folklore, the god of wealth represents the five directions. The five directions refer to the east, west, south, north, and center, indicating that wealth can be obtained from all directions. In Shanghai, there is a tradition of “Qiang Lu Tou” (Snatching the Road Head) during the lunar New Year. On the night of the fourth day of the first lunar month, people prepare sacrificial offerings, pastries, candles, and other items. They play gongs and drums, burn incense, and worship the god of wealth with great devotion. The fifth day is believed to be the birthday of the god of wealth, and in order to seize prosperity in the market, the “Qiang Lu Tou” ceremony is held on the fourth day to receive the god of wealth.

“Wu Si” (Fifth Sacrifice) refers to the worship of household gods, kitchen gods, earth gods, door gods, and deities related to travel, collectively known as the “Road Head.” When receiving the god of wealth, it is customary to offer sheep’s head and carp. Offering a sheep’s head symbolizes auspiciousness, and offering carp represents the homophonic word for “fish” and “surplus,” implying good fortune. People firmly believe that as long as the god of wealth is appeased, they will become wealthy. Therefore, during the New Year, people open their doors and windows at midnight on the fifth day of the first lunar month, light incense, set off firecrackers, and fireworks to welcome the god of wealth. After receiving the god of wealth, they also have to drink “Lu Tou Jiu” (Road Head Wine), often continuing until dawn. Everyone is filled with hopes of becoming prosperous and wishes for the god of wealth to bring gold, silver, and treasures into their homes, leading to great wealth and fortune in the new year.

As the act of disposing of garbage is prohibited from the first to the fourth day of the lunar month to avoid discarding the “wealth energy,” on the fifth day, the garbage is no longer considered “wealth energy” but “poor soil.” Therefore, on this day, it is essential to discard the garbage and “send poverty out of the door.”

- Breaking down the Chinese character “生” (shēng) into “牛一” (niú yī).

- The meaning is that a male is destined to work hard like an ox or a horse from the moment he is born, and reaching adulthood represents becoming significant, hence “牛一” (niú yī) symbolizes a grown man.

Chinese Cow vs Goat

In Chinese culture, both cows and goats hold significance and have been featured in various aspects of traditional beliefs, folklore, and symbolism. Here are some key points regarding the cultural significance of cows and goats:

Cow: