If you have been to China or seen different pictures of the country, you’ll notice one thing stands out the most – dragons. You’ll find dragons incorporated in different architecture in China from colorful paintings to huge and majestic statues. They are also incorporated in many of the Chinese festivities, like Dragon boat racing or the Dragon dance is done on almost every occasion.

Dragons hold a very important position in China. In this post, we are going to look at what the dragon symbolizes in Chinese culture and the mythologies that surround it. We’ll also look at the different types that exist and what they stand for.

what is the Chinese dragon?

The dragon is an animal from ancient Chinese mythology and is considered one of the symbols of the Chinese nation. According to legend, dragons have scales like fish and can fly, transform, and control the weather. Alongside the phoenix and qilin, dragons are regarded as auspicious creatures, often associated with imperial power in ancient times. The Chinese dragon is a mythical creature that combines features of fish, crocodile, snake, pig, horse, ox, and other animals, as well as natural elements like clouds, lightning, and rainbows. It has a history of approximately 8,000 years. As a participant and witness of the great fusion of the Chinese nation, the spirit of the Chinese dragon represents unity and cohesion. Additionally, the dragon is associated with water and is responsible for bringing rainfall and managing water, reflecting its mission to benefit humanity. In modern society, the dragon has gradually evolved from a mythical creature to a symbol of good luck. As a symbol, the dragon represents concepts such as soaring, invigoration, exploration, and transformation. Therefore, the spirit of the dragon signifies the spirit of striving and pioneering.

what is the Chinese dragon called?

The Chinese dragon is called “Long” (龙) in Chinese. The term “Long” specifically refers to the mythical creature of the dragon in Chinese culture. It is one of the most iconic and revered symbols in Chinese mythology and folklore. The Chinese dragon is distinct in its appearance, often depicted as a long, serpentine creature with scales, claws, and a prominent mane. It is associated with numerous positive qualities such as power, wisdom, prosperity, and good fortune. The Chinese dragon holds a significant place in Chinese history, art, and symbolism, and it is deeply ingrained in Chinese culture as a symbol of national identity and cultural heritage.

The correct English transliteration for 龙 (Long) is “dragon.” The term “loong” you mentioned is not the standard English translation for the Chinese dragon. While the pronunciation of “loong” may be closer to the Mandarin pronunciation, the widely accepted English term for the Chinese dragon is simply “dragon.” It is important to note that the Chinese dragon and the European dragon (often associated with mythology and folklore) are distinct creatures with different cultural significance and characteristics.

Alternate Names and Beautiful Titles of the Dragon: There are various alternate names and beautiful titles for the dragon, including Hui, Qiu, Qinglong, Yunchi, Panchi, Jiaolong, Jiaolong, Huolong, Jinlong, and more.

Hui: Hui is an early type of dragon that was imagined based on reptiles, particularly snakes. It is often associated with water and is considered the juvenile stage of a dragon. Hui dragons were depicted in the late Western Zhou period on bronze decorations, although they are not as common.

Qiu: Qiu refers to dragons that have not yet grown horns. It is a term used for dragons in their growing stage.

Panchi: Panchi refers to serpent-like mythical creatures in the dragon family. They are early dragons that do not possess horns.

Jiao: Jiao generally refers to scaly dragons associated with the ability to cause floods. It is believed that Jiao dragons, once they enter water, can create clouds and fog, and soar into space.

what is the Chinese dragon made of?

The dragon’s appearance has varied throughout different periods in Chinese history, from thousands of years ago in undocumented cultural eras to the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties, and later in the Warring States and Pre-Qin periods. Vessels and decorations depicting dragons have always been abundant, featuring winged or wingless, horned or hornless variations. The animal-bodied dragons of the Liangzhu culture and the serpent-dragon of the Chahe archaeological site exhibit significant differences in their imagery. Therefore, some scholars believe that the dragon’s form has multiple origins and sources.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, the dragon’s portrayal featured a robust and plump body, resembling a snake. In the Song dynasty, scales appeared on the back and tail, with a row of fins on the tail. With characteristics reminiscent of a lion, it had a round and chubby body, and a mane behind its head. During the Tang dynasty, forked deer antlers emerged, although initially they were somewhat similar to regular deer antlers. The upper lip was long and pointed, while the lower lip was short and did not roll downward. Dragon wings took on a flowing ribbon-like form. In the Song dynasty, four-clawed feet became prominent, with the hind legs often intertwining with the tail in a coiled fashion.

what does Chinese dragon look like?

The dragon, known as “Long” (龙) in Chinese, is a creature from ancient Chinese mythology and one of the symbols of the Chinese nation. The “Er Ya Yi” describes it with features such as antlers like a deer, a head like a camel, eyes like a rabbit, a neck like a snake, a belly like a mirage, scales like a fish, claws like an eagle, paws like a tiger, and ears like a cow. The “Lun Heng” mentions a common depiction with a horse’s head and a snake’s body. The “Huainanzi” records five types of dragons: flying dragon, winged dragon, snake dragon, flood dragon, and spiral dragon.

The Song Dynasty painter Dong Yu believed that the dragon had antlers like a deer, a head like a cow, eyes like a shrimp, a mouth like a donkey, a belly like a snake, scales like a fish, feet like a phoenix, whiskers like a human, and ears like an elephant. In the Ming Dynasty, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” states: “The dragon is a creature with long scales. Wang Fu describes its form with nine similarities: a head like a camel, antlers like a deer, eyes like a rabbit, ears like a cow, neck like a snake, belly like a mirage, scales like a carp, claws like an eagle, and paws like a tiger. It has 81 scales on its back, representing the yang energy of the number nine. Its voice is like the clash of bronze plates. It has whiskers beside its mouth, a bright pearl under its chin, and reverse scales under its throat.”

According to general depictions, the dragon has a snake’s body, a pig’s head, deer’s antlers, cow’s ears, goat’s whiskers, eagle’s claws, and fish’s scales. In the ancient tribal society, the Huaxia tribe in the Yellow River Basin, which had the snake as its totem, conquered other tribes and absorbed their totems, combining them into the dragon totem.

According to legend, dragons are capable of flying, shape-shifting, and controlling the weather. They are often considered auspicious creatures alongside the phoenix and qilin, symbolizing imperial power in ancient times. There are mythical stories such as “drawing a dragon and adding the finishing touches,” “Nezha stirring up the sea,” and “Sun Moon Lake.”

Ancient Chinese people believed that dragons governed rainfall, which determined agricultural harvests. The success of agriculture determined people’s livelihoods, making the dragon the primary “totem” in agrarian society.

Each part of the dragon carries specific symbolism: the prominent forehead represents intelligence and wisdom; deer antlers symbolize prosperity and longevity; ox ears signify being at the forefront; tiger eyes portray dignity; demonic claws depict bravery; sword-like eyebrows symbolize valor; lion’s nose represents preciousness; a golden fish tail symbolizes agility; and horse teeth symbolize diligence and kindness.

Why Dragon Is Famous in China

Unlike in Western cultures where Dragons are protagonist creatures in every story, in China, they are considered benevolent and majestic creatures that are kind and bring luck. The dragons are considered important because they are believed to be present during the earth’s creation according to the Chinese.

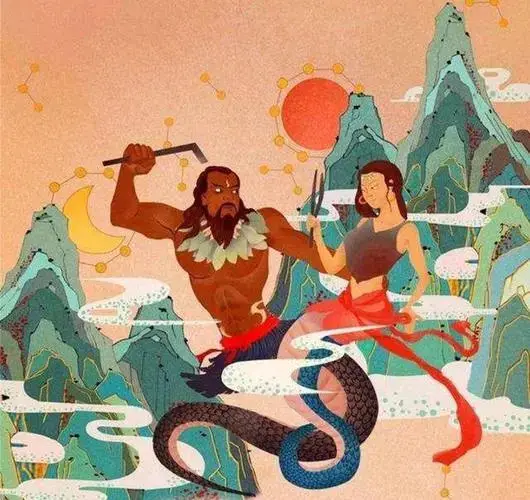

The Chinese believe that the goddess Nu Kua, who was part dragon, created the earth. She then put up four pillars with a dragon at the top to hold up the heavens. The goddess then created humanity, meaning the Chinese were directly linked to dragons from the very beginning. After the great floods caused by the Dragon kings, Nu Kua came back to earth to repair the damage. She released a legion of dragons to walk among people and aid them. They maintain that after humanity was created, dragons lived among the people teaching them essential skills to survive. The dragons are considered angels of the Orient and represent the balance of all things in the world.

It is also believed that a dragon helped the Yellow Emperor of the Han dynasty, the first imperial line in Ancient China, to begin the prelude of Chinese civilization. The Yellow Emperor was believed to have worked with Yandi a legendary tribal leader, born through his mother’s strong telepathy with a mighty dragon. So, you see, the dragons seem to have played a big role in China’s evolution. That is why they were used as symbols for the Chinese emperors and later among the twelve symbols of the national emblem of the Republic of China.

Why Is the Dragon A Symbol of China?

As mentioned, in Ancient China, Emperors used dragons as their symbols. The dragon was a symbol of the divine power of the emperors and their mighty rule over the land. The Yellow Emperor was even believed to have been reborn as a dragon after his death.

The emperors especially used the yellow/golden dragon with five claws as their symbol. The princes and other royal male members used dragons with four claws as their symbols. The wives and empresses of the emperors used the phoenix as their symbolism. This was because Feng Huang (a phoenix-like bird) ruled over all birds, and was seen as the perfect feminine entity to be paired with the Dragon.

These symbols were embroidered in their robes which they wore as a sign of honor. For these reasons, only a select few outsides of the royal family were permitted to adorn dragon robes and jewelry. The common subjects also had dragon paintings and other artifacts in their homes as a symbol of good luck and fortune.

These symbolisms and culture have been carried forward to today, where the Chinese still use the dragon as a symbol of excellence and power. Although it’s no longer a part of the twelve symbols of the national emblem of China’s flag, it is still an important symbol. The Chinese still compare outstanding and successful people to dragons, because dragons represent traits many Chinese admire and wish to emulate.

What Does the Dragon Represent in Chinese Culture?

The Chinese dragon is also known as Lung, Loong, or Long. In Chinese culture, mythology, and folklore, it is considered to be a legendary creature. Unlike in western cultures, the Chines revere the dragon which is seen as benevolent symbols in their culture. According to the Chinese, the dragon is said to resemble many animals. It’s described as having a long tail like that of a snake, with scales like fish and claws similar to those of hawks. They also have antlers like deer’s, a nose similar to a dog’s, a big mouth like a bull, whiskers that resemble a catfish’s, and a mane around its face like a lion’s.

In Ancient China the dragon was seen to represent, divine power, strength, good fortune, and success. That is why dragons were used to symbolize Emperors. Based on the dragon’s attributes, they symbolized the emperors’ nobility, dignity, and wisdom, depicting them as courageous heroes to their subjects. Traditionally, the Chinese also believed that dragons were auspicious powers that had power over the water element and are believed to reside or have resided under large water bodies. They were believed to have power over any body of water, from lakes, rivers, seas to waterfalls. As powerful water spirits, they could command rains, floods, and typhoons. As such, they were seen to have power over seasons and harvest.

Today, the dragon has become a mascot of the Chinese culture representing the people’s pioneering and unrelenting spirit to keep up with the changing times. Based on past beliefs, the dragons generally symbolize the following in Chinese cultures today:

Nobility. Because dragons were used to symbolize the emperor, anyone born in the Year of the Dragon is considered to be more noble and prosperous than the rest. They are considered to be wise, decisive, confident, and strong-willed.

Good fortune. These mystical creatures were believed to be a source of good luck to those they favored. Today, Chinese engrave dragon depictions on their items or as tattoos to attract success and good luck.

A sign of kindness. In western culture, dragons are depicted as aggressive evil creatures that breathe fire. On the other hand, the Chinese view dragons as beautiful creatures that are symbols of warmth and kindness. This is related to the belief that dragons were sent on earth to aid humans.

Masculinity. In the past, men were considered more dominant and influential in the community. As such, they were seen as the mystical manifestation of the dragon. Today, dragons are still used to symbolize male vigor and fertility.

Agriculture. These water spirits are believed to have control over the weather. The male dragons are said to have the power to fly to the heavens and bring rainfall. Hence those who believe in them and worship them, normally pray to them for rain and a good harvest.

Different Types of Dragon Colors and Their Meanings.

According to Chinese Mythology, dragons were beautiful and colorful creatures. Each of their colors carried a special meaning in Chinese culture. The following are the most notable colors and what they symbolize:

Green and Blue.

Blue and green are generally associated with growth, nature, and serenity in Chinese culture. The green and blue dragons were normally the Eastern dragons and they symbolized the beginning of spring, with clear skies and new growth. They were also seen to symbolize health, harmony, and prosperity. As such people looked at them as representations of healing, peace, and rest. They also represent the East cardinal direction.

White.

In the Chinese spectrum of Yin and Yang, white represents the active masculine energy that’s the Yang. In many cultures white is seen as a symbol of purity, however, in China, it is also seen as a symbol of death and mortality. Based on this, the white dragon is seen as a symbol of purity but also as a bad omen for death. It also represents the West and autumn season.

Black.

As the other half of the Chinese spectrum, black represents passive feminine negative energy known as Yin. The black dragon is normally associated with vengeance and power and is often believed to cause storms and floods. In terms of seasons and directions, it is also considered to symbolize the North and the winter season.

Red.

Traditionally, red is associated with good luck and fortune and is often used in many large and happy celebrations in Chinese culture. For this reason, the red dragon is the focus on happy occasions like weddings and festivities like Chinese New Year. Aside from luck the red dragon also symbolizes passion, creativity, and vitality. It also represents the South and summer season.

Yellow.

In Chinese culture, yellow is seen as a symbol of warmth, wealth, solidity, and nobility. It is normally a color set aside for those belonging to the higher class. The yellow dragon was considered the most powerful and superior dragon, which is why emperors used it as a symbol of their rule.

9 Types of Chinese Dragons.

According to Chinese culture and mythology, there are a variety of different dragons. All the dragons have been classified into 9 main categories. The categories are as follows:

Celestial Dragon.

Its Chinese name is Tien Lung. It is a flying dragon that is believed to guard the heavens and pull the divine chariots. It’s considered a very important dragon that resides in the sky because its main duty is to prevent the gods from falling from the sky.

Dragon King.

Its other names are dragon god or Longwang. It is considered a very powerful dragon that rules the China sea in all four directions. It is said to appear in different forms but is often depicted as human. It is also a water god with the ability to cause rain and is considered the yang personification of masculine power.

Winged Dragon.

In Chinese is referred to as Yinglong, some also call it the responding dragon. Unlike other dragons, its wings make it unique. It is a water deity, commonly associated with rain and floods.

Hidden Treasure Dragon.

This dragon is referred to as Fuzanglong in Chinese. It is said to be a guardian residing in the underworld where it hoards and protects different types of buried treasure, both man-made and natural. It is also associated with volcanoes since it is said that it forms volcanoes each term it comes out of the underworld to go report in heaven.

Coiling Dragon.

It’s also called Panlong in Chinese. It is a lake dragon that is restricted in water and can never ascend to heaven. It is said to be able to control time. Sometimes referred to as river dragon and said to resemble the crocodile.

Spiritual Dragon.

It’s blue. It is said to have power over the rain and wind. It has to use the rain and wind to benefit the humans on earth.

Yellow Dragon.

Some people refer to it as Longma the winged horse with scales, that lives in water. It is believed that it emerged from Luo River to teach the emperor Fu Shi the Chinese writing ba gua. Other’s refer to it as Huanglong, the dragon reincarnation of the Yellow Emperor.

Horned Dragon.

It’s also referred to as Lung in Chinese by some people. It is considered to be the most powerful dragon, despite being deaf. It was, however, never considered evil. It was also believed to have power over the rain.

Hornless Dragon.

Others refer to it as scale dragon or crocodile dragon or Jiaolong in Chinese. Others call it Il. It is said to commonly give resided in the river, although some say it lived in the oceans. It was said to be the ruler of all aquatic animals.

What Is the Rain Dragon in Chinese Mythology?

In Chinese mythology, the rain dragon was also referred to as thunder god or a god dragon or Shenlong in Chinese. He is described as having a human head and a dragon body with a drum-like stomach. He is considered to be a significant dragon that has power over the weather. He can control the clouds rains and wind, which all affect agriculture. So, to ensure they had a good harvest, the Chinese would avoid angering the Shenlong. Angering him would mean drought, thunderstorms, and general bad weather.

Why Is Dragon in Chinese Zodiac?

In the Chinese calendar, 12 animals each represent a year in a twelve-year cycle as the Chinese Zodiacs. Each of these animals has certain traits. The Dragon is the 5th animal in the Chinese Zodiac. It is included because it is the only creature that is mythical, hence unique. It is also important as it symbolizes good fortune, good health, prosperity, and balance. As such, dragon years are a popular time when many children are born. It is believed that children born during the Dragon years are said to be lucky and honorable and will grow up to be very successful compared to the rest.

Chinese dragon history

Ancient Times

In the late Neolithic period, jade dragons exhibited ancestral forms, indicating a direct correlation between the emergence of dragons and the animals revered and feared by the local tribal ancestors of that time and region. This association is related to the animal population present in the area during that period.

Shang and Zhou Dynasties

During the Shang and Zhou dynasties, dragon culture gained widespread dissemination, transforming the primitive dragon imagery of the totemic era into true dragon motifs. The Shang dynasty attached great importance to religion and witchcraft, which led to a significant focus on the casting of bronze ritual vessels, essential for religious activities. These bronze vessels showcased various symbolic patterns, displaying deities to be revered and sought for protection. Among these patterns, dragon motifs became a predominant element.

From the Shang Dynasty to the unification of the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC, after more than 1,400 years of evolution, the shape of the dragon gradually took form. From the excavated “C-shaped” jade dragons, their bodies were smooth like snakes, with pig-like mouths. This represented the early form of dragons and was considered a symbol of wealth and status. In feudal dynasties, wealth and status held great importance. During the Zhou Dynasty, the phoenix was also highly regarded by the royal family and was on par with the dragon, leading to the emergence of the motif of the dragon and phoenix dancing together.

Pre-Qin Period

Originally revered by the ancient Chinese ancestors, dragons gradually became associated with the expanding monarchic power and the imperial families as their authority grew stronger. Records in “Lüshi Chunqiu” depict Duke Wen of Jin being likened to a dragon, and the subsequent notion of the First Emperor of Qin being the “Ancestral Dragon.” After the Qin and Han dynasties, the dragon became firmly established as the embodiment of imperial power and an exclusive symbol of the royal household.

During the Qin and Han Dynasties, a period of great unification in China, significant changes occurred as a result of cultural standardization. This marked the unification of the dragon as well. Although the Qin Dynasty was short-lived, it played a significant role in Chinese history. During this period, the dragon’s head became larger and its body became thicker, departing from the slim and elongated dragon of the Zhou Dynasty. The enlarged dragon appeared more fierce and formidable. The Han Dynasty further enriched the image and culture of the dragon, considering it as a totem with great significance, as it was an era of unified rule.

Han Dynasty Period

In the Western Han dynasty, Dong Zhongshu’s “Chunqiu Fanlu” mentions folk activities of praying to the dragon for rainfall and abundant harvests. Dragon imagery is also found in famous silk paintings unearthed from the Han tombs in Mawangdui, Changsha, indicating that during the Western Han period, the dragon had become a widely circulated cultural symbol in society. During the Eastern Han dynasty, dragons had a robust and tiger-like body shape, distinct separation between the body and tail, and some had fins. The horns resembled those of a cow or deer. There were raised ridges below the horns, curving upward at the tips, similar to deer antlers. Dragons had wings and longer animal legs, with a predominant tiger-like form and additional elements of other animal shapes.

Wei and Jin Dynasties

From the Jian’an period to the Wei and Jin dynasties (including the Sixteen Kingdoms era), dragon bodies became slender and elongated, tiger-like in appearance, with distinct separation between the body and tail. The horns slightly resembled deer antlers, and wings varied between being present or absent. Dragons with wings retained a bird-like wing shape, and their legs resembled those of animals.

Tang and Song Dynasties

In the Sui and Tang Dynasties, there were further changes to the dragon. In the early historical records of the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the dragon’s mouth became larger, and its horns started to branch out. These changes were inherited by subsequent dynasties. By this time, the dragon had become well-established, and dragon culture was reinforced. The fish-scale pattern on the dragon’s body was established during the Tang Dynasty. During the Song Dynasty, dragon culture became stable. The dragon’s image during this period included deer antlers, camel heads, ghostly eyes, snake bodies, fish scales, eagle claws, tiger paws, ox ears, fish fins, and fish whiskers. In comparison to the Song Dynasty, the dragon during the Yuan Dynasty had a more elongated head, smaller yet expressive eyes, and a robust body. Dragon claws mostly featured three digits, with fewer instances of four digits.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, dragons regained a robust and plump body, resembling a snake. The body and tail were undifferentiated, and scales covered the back and tail. In the Tang dynasty, forked deer antlers appeared. The upper lip was elongated and pointed, and the lower lip was short without rolling downward. Dragon wings took on a flowing ribbon-like form. In the Song dynasty, dragons had four-clawed feet, with the hind legs often intertwining with the tail in a coiled fashion. A row of fins adorned the tail, incorporating characteristics of a lion, featuring a round and full shape with a mane behind the head.

Ming Dynasty

In the Ming dynasty, dragon motifs exhibited a powerful and majestic appearance, with imposing and vigorous dragon heads. During the Qing dynasty, dragon motifs displayed a luxurious and intricate style, characterized by grandeur and splendor.

The dragon during the Ming and Qing Dynasties solidified the current image of the dragon. During this period, the dragon appeared more majestic and symbolized imperial authority. The representation of dragons in folk culture gradually became controlled, and dragons were primarily associated with the imperial family. The five-clawed golden dragon was used to symbolize the emperor. In the clothing, such as dragon robes, there was a focus on the front-facing dragon with an emphasis on drawing the dragon’s head, giving it a more domineering appearance. Over thousands of years, the evolution and development of the dragon represent a cultural history that witnesses the wisdom of the Chinese nation, creating a mythical creature that became a totem of national belief.

Chinese dragon origin

Dragons originated from snakes.

Eight thousand years ago, with abundant rainfall and lush vegetation, the world was a paradise for snakes, and humans had to constantly guard against them. As a result, people imagined a creature with a snake’s body, camel’s head, qilin’s horns, turtle’s eyes, ox’s ears, lizard’s legs, tiger’s claws, fish scales, and even whiskers—a dragon. Dragons were believed to possess incredible divine powers, capable of subduing all natural disasters and wild beasts.

Originating from thunderclaps

Dragons were initially associated with the twisting and turning image of lightning. Through observations of nature and celestial phenomena, ancient people believed that there existed a divine being in the heavens that could control winds, rain, and thunder, and appeared in the form of lightning. Based on the sound of thunder, they named this creature “dragon.” In terms of pronunciation, the Chinese word for dragon, “lóng,” captures the rumbling sound of thunder.

In weather conditions with dark clouds, whenever they witnessed gusts of wind, heard the rumbling of thunder, and even saw accompanying lightning, the ancient people knew that the dragon had arrived. The enigmatic nature of dragons both puzzled and frightened them, instilling a sense of awe. Thus, the worship of dragons began.

where are Chinese dragons from?

China has many origins of dragon culture, with legends originating from Fuxin, Liaoning, and Dongting Lake.

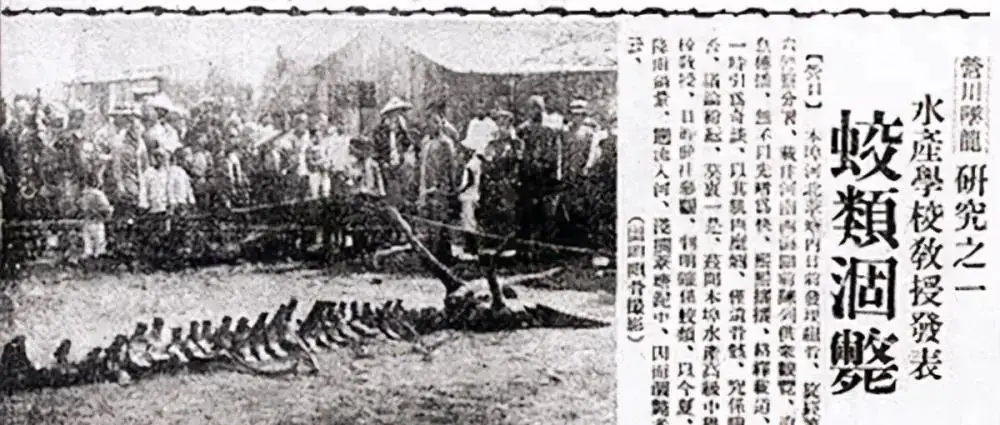

Ancient Tombs in Henan Province

The earliest appearance of dragons dates back 5,000 years ago in a primitive society’s tomb, currently displayed in the Museum of Puyang City, Henan Province. It is a dragon made of shells, with a rugged appearance resembling a lizard, lacking vibrant colors. Archaeologists refer to it as the “First Dragon of China.”

In ancient times, people couldn’t provide rational explanations for many natural phenomena. They hoped that their national totem possessed the powers of wind, rain, thunder, and lightning. They wanted it to resemble the majestic mountains, swim in water like fish, and soar in the sky like birds. Therefore, various animal features were concentrated in the dragon, such as the head of a camel, the neck of a snake, the antlers of a deer, the eyes of a turtle, the scales of a fish, the paws of a tiger, the claws of an eagle, and the ears of a cow. This composite structure signifies that the dragon is the king of beasts, an omnipotent creature, and a universal deity.

It’s important to note that dragons only have five fingers; any creature with four fingers is not a dragon but a lizard or crocodile-like animal.

As the totem of the Chinese ancestors, the dragon started as a rough and simple stone taken from the wild mountains. Throughout history, it was continuously shaped and refined by the elderly. The Shang and Zhou dynasties bestowed it with dignity, the Han and Tang dynasties with magnificence. During the Wei and Jin periods, it became like the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, possessing an ethereal and scholarly aura. In the Liao and Jin dynasties, it resembled the wild horses of the grasslands, galloping without restraint. Emperors and nobles elevated it to the highest status, while common people embraced it in their local customs.

Shucheng County

Shucheng County is located in the middle-western part of Anhui Province, on the eastern foothills of the Dabie Mountains. It borders Lujian County to the east, Tongcheng City and Qianshan County to the south, Yuexi County and Huoshan County to the west, and Liuan City and Hefei City to the north. The total area of the county is 2,092 square kilometers, with a population of 1.02 million people (as of the end of 2010). It is one of the forefront areas for industrial transfer and a part of the Hefei Economic Circle.

Shucheng County is one of the origins of dragon culture in China and one of the thirteen places associated with the Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai legend. The phrase “dragon-shu land” often mentioned refers to the Shucheng area.

According to legends in this small county town, the local people call themselves “descendants of the Dragon Shu.” It is said that in ancient times, there was a country called “Dragon Shu Marquisate” in this area, with its capital located at Longhekou in Shucheng County, Anhui Province.

In the first year of Yongping (58 AD), in the month of April, Emperor Ming conferred the title of Marquis of Dragon Shu to Xu Chang, the uncle of King Chu Liu Ying, granting him the counties of Shu and Dragon Shu. According to historical records, the “Dragon Shu Marquisate” was the first titled state in history to bear the word “dragon.” Longshu County (Marquisate) took its name from the ancient country of Shulong, recorded in the “Chinese Historical Atlas.” According to the “Zuo Zhuan,” in the twelfth year of Duke Wen, the “Shulong” rebelled against Chu and was later destroyed by Chu, becoming its vassal. It belonged to the Nine Rivers Commandery during the Qin dynasty.

During the reign of Emperor Gaozu of Han, in the fourth year, Shu County was established, and in the fifth year, Dragon Shu County was separated. According to the annotations of Du in the “Zuo Zhuan,” “Shu had Dragon Shu to the southwest. It was a marquisate in the Eastern Han dynasty, and the county was abolished during the Six Dynasties period.” Yao Nai stated that it was located north of present-day Huaining County, south of Tongcheng County.

According to the “Annals of Anhui Province: Historical Evolution,” the Dragon Shu City ruins are located at the present-day Longhekou in Shucheng County.

In the seventh year of Emperor Gaozu (200 BC), Liu Xin, the nephew of Emperor Gaozu, was titled the Marquis of Gengjie, governing Shu and Dragon Shu counties. Liu Xin built the Seven Gates Weir in his fiefdom, which became one of the important ancient water conservancy projects in our country.

The tomb of Liu Xin, commonly known as Shuwangdun, is located in the current Sihou Township on the north bank of the Fengle River in Feixi County (originally part of Shucheng County).

Fuxin, Liaoning Province

The “Dragon-shaped Mound Sculpture” unearthed from the Chahai Primitive Village Site in Fuxin, Liaoning Province, provides evidence for our “time positioning.” The Chahai site belongs to the “Hongshan Culture” remains, dating back approximately 8,000 years. The “Dragon-shaped Mound Sculpture” is located in the central square of this primitive village site and is constructed from equally-sized reddish-brown stones. The stone dragon is nearly 20 meters long, two meters wide, with an uplifted head, a curved back, and a tail that is partly visible. This stone dragon is the earliest and largest known dragon discovered in China to date. (There are claims of a fish-tailed deer dragon rock painting dating back 10,000 years on the Shizitan Cliff in Jixian County, Shanxi Province, but this rock painting hasn’t been published, so its exact appearance is unknown.) There are also pottery dragons with a history of 7-8,000 years unearthed from Xinglongwa in Inner Mongolia, as well as colorful pottery neck bottles with dragon patterns dating back 7,000 years unearthed from the Beishouling site in Baoji, Shaanxi Province, and a carved dragon from shellfish dating back over 6,400 years found in Xishuipo, Puyang, Henan Province.

The process of the dragon’s vague collection started during the Neolithic Age and went through significant development from the Shang and Zhou periods to the Warring States period. It reached its basic form during the Qin and Han dynasties. The term “basic” has two meanings: first, the framework, elements, and style that constitute a dragon were essentially present during the Qin and Han dynasties; second, the dragon is an open and constantly evolving system. It did not remain content with its basic form during the Qin and Han dynasties, but continued to evolve and develop throughout subsequent dynasties until today.

Dongting Lake

Two thousand three hundred years ago, a poet and philosopher wandered along the shores of Dongting Lake. Sometimes he lowered his head and pondered, sometimes he looked up at the sky and exclaimed. In his exquisite poems, he poured out the doubts accumulated in his heart:

Who transmitted the knowledge of the ancient beginnings?

When the heavens and earth were not yet formed, what evidence can we rely on?

Day and night, water pervades, everything is in darkness.

Who can distinguish the limits?

The movement of the celestial bodies fills the void without form.

How can we recognize the heavens and earth?

Yu employed the Yinglong.

How were the rivers and seas connected?

How did the Yinglong use its tail to mark the earth?

The rivers flow into the ocean, what experiences did they undergo?

Sunlight reaches everywhere,

How can the candle-like dragon continue to shine?

The sun has not yet risen,

Why does the divine tree radiate light?

This scholar was Qu Yuan, a famous poet of the Spring and Autumn period.

The above poem is from his work “Questions to Heaven.” In the poem, Qu Yuan raises over a hundred questions, ranging from nature to society, from history to legends. He boldly expresses his doubts, and even the mythical creature “dragon” does not escape his keen observation. According to legend, during the time of Dayu’s flood control, an “Yinglong” (a winged dragon) used its tail to mark the earth, indicating the route to divert floodwaters. This is said to be the origin of the vast rivers and streams in later times.

why Chinese emperor is called a dragon?

According to legends, there are two human ancestors in Chinese mythology: Fuxi and Nüwa. Fuxi is one of the Three Sovereigns and the cultural originator of the Chinese ethnic group. He is considered the divine protector of the state and the earliest recorded creator god in Chinese literature. Nüwa is the goddess of creation in ancient Chinese mythology and also holds the titles of cultural originator of the Chinese ethnic group and divine protector of the state. Both of these ancestral figures have a human head and a dragon or snake body, and they are collectively referred to as “Dragon Ancestors.”

In addition, there is a legend about the Emperor of Heaven appointing Gun to control flooding, but when Gun failed, he was killed. Gun’s corpse remained uncorrupted for three years. The Emperor was amazed and ordered Gun’s abdomen to be cut open, and a yellow dragon emerged, which transformed into Yu, the legendary founder of the Xia dynasty. Yu became the leader of the Xia tribe, and the dragon became their totem. The Records of the Grand Historian state that before the birth of Liu Bang, the mother dreamt of a divine visitation with thunder and lightning. Liu Bang’s father saw a dragon coiling around his mother’s body, and later, Liu Bang was conceived and born. Liu Bang declared himself emperor and proclaimed to be the true dragon emperor. Since then, the dragon became exclusively associated with feudal rulers.

Originally, the dragon was an object of worship for the early Chinese people, but as the level of autocracy increased and the power of the monarchs expanded, the dragon became appropriated by the imperial family due to their political advantage.

After being deified, the dragon became intertwined with the worship of emperors. During the Shang and Zhou dynasties, dragon patterns officially became the imperial emblem and symbol of power. At that time, the emperors of the Shang and Zhou dynasties flew the Nine-Dragon Flag and wore dragon robes for ancestral worship. During the Qin and Han dynasties, when China was unified, there was a need for a unifying deity that could integrate the beliefs of various regions and ethnic groups. The worship of the dragon further merged with the worship of emperors.

In ancient China, emperors proclaimed themselves as the incarnations of dragon gods or sons of dragon gods. They claimed to be protected by dragon gods and used the dragon symbol to establish authority and gain the trust and support of the people. In this way, the dragon acquired a more prominent status and played a crucial role in the development of Chinese dragon culture.

The Lüshi Chunqiu records the comparison of Duke Wen of Jin to a dragon, and later, there were claims that Qin Shi Huang was the “ancestor dragon.” After the Qin and Han dynasties, the dragon became firmly established as the embodiment of emperors and an exclusive symbol of the imperial family. The emperor was referred to as the “True Dragon Emperor,” their birth was described as the “Descent of the True Dragon,” and their passing was called “the Dragon Ascending to Heaven.” Their residence was the Dragon Court, their bed was the Dragon Bed, their seat was the Dragon Throne, and they wore Dragon Robes.

Chinese dragon culture

Dragons in various aspects of cultural life, including religion, politics, painting, literature, and folk festivals:

Dragons and Religion: Dragons are believed to have the ability to ascend to the heavens. During the Shang and Zhou dynasties, a flourishing period for bronze casting, the progress in decorative art accompanied the development of primitive religion. The dragon motif, as the controlling force and celestial being, had religious significance and evoked feelings of terror and mystery.

Dragons for rainmaking: As an ancient agricultural society, China’s crops and people’s livelihoods were directly influenced by weather conditions. Rainmaking rituals, including dragon-related practices, were an essential part of ancient witchcraft.

Establishment of Dragon Gods: In traditional Chinese religious beliefs, dragons have always been regarded as celestial beings that control the heavens and rainfall. The transformation of dragons into deities and their appointment as Dragon Kings can be attributed to the influence of Buddhism and the association with Taoism. The emergence of Dragon Kings in history reflects the aspirations of the common people to protect their rights and pursue a better life. However, Dragon Kings were ultimately products of ignorance and backwardness and were eventually abandoned by the enlightened populace.

Dragons and Politics: The representation of dragons, particularly through dragon motifs in ancient Chinese art, gradually developed during the pre-Qin period, benefiting from the unification of the Western Zhou dynasty and the conflicts of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. The Qin dynasty’s complete unification of the six states further promoted the development of dragon motifs. Dragons in this era still possessed their religious symbolism as celestial beings, but their secular significance as auspicious creatures became increasingly important. People hoped for the protection and blessings of these divine creatures. The dragon motifs of the Qin and Han dynasties already exhibited a significant secularization, and the dragon was no longer associated with the terrifying image of the Shang and Zhou periods. With the deep-rooted belief in the divine right of kings in ancient Chinese society, the concept of the Son of Heaven and dragon lineage gradually gained social acceptance. Emperors proclaimed themselves as the embodiment of dragons, identifying themselves as the heavenly beings sent to maintain order on Earth. Thus, the concept of the true dragon emperor emerged in later periods.

In the class society that followed, rulers continued to exploit the idea of totem worship to maintain their rule. They proclaimed themselves as the reincarnation of dragons, acting as the intermediaries between heaven and earth. Starting from the 2nd century, the dragon became a symbol of emperors and power. Dragon motifs adorned imperial regalia, clothing, and furniture, effectively monopolizing the image of the dragon. The general population, enticed or coerced by the power, had no choice but to recognize the rulers as the reincarnation of dragons and accept their rule, sometimes even believing that they might have a connection with dragons themselves, as depicted in idioms like “the carp leaping over the Dragon Gate.”

Dragons in Painting: The earliest known expert in painting dragons in Chinese history was Cao Buxing from the Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period. According to the evaluation by Xie He, a scholar from the Southern Dynasty, “In the secret chamber, there is only one dragon. Its style is not merely an empty creation.” Later, the renowned Eastern Jin painter Gu Kaizhi included the image of a dragon in his masterpiece “The Nymph of the Luo River.” Notably, during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Zhang Sengyao became the most legendary dragon painter in Chinese history. He painted dragons in Anle Temple in Jinling, giving rise to the idiom “adding the finishing touch by painting a dragon.” Skilled dragon painters emerged in various dynasties throughout history, and the dragon’s image has been perpetuated in Chinese painting.

Dragons in Literature: Dragons held a certain position in ancient religious and political beliefs, and dragon motifs were popular in daily life, making them a common subject in literature. In the earliest collection of poems, the “Book of Songs,” dragon imagery primarily appeared in relation to Zhou kings, feudal lords, and ceremonial rituals, seemingly distant from the people’s daily lives. In the “Chu Ci” (Songs of Chu) from the Warring States period, poets often likened themselves to divine dragons to express their noble character, ambitious political aspirations, and frustrations. In later literary works such as “The Investiture of the Gods,” “Journey to the West,” and “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio,” the dragon’s image became more diverse and elaborate. The majestic and powerful appearance, divine and mystical characteristics, and complex background of dragons inspired the imagination of writers, enriching Chinese literature.

Dragons in Folk Festivals: Chinese folk festivals include several celebrations related to dragons. These festivals feature a variety of colorful activities with a strong ethnic flavor and a sense of rustic charm. The Lantern Festival, also known as the Yuanxiao Festival, held on the fifteenth day of the lunar month, involves dragon lantern dances. The Dragon-Head-Raising Festival, held on the second day of the second lunar month, is believed to be the day when hibernating dragons awaken. The Dragon Boat Festival, celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, includes dragon boat races as an essential part of the festivities. Dragons add vibrancy to Chinese folk festivals, bringing hope and joy to people’s lives.

The Chinese dragon serves as a totem of the Chinese nation and a symbol of Chinese culture. Ancient people believed that there must be a powerful “divine creature” associated with water, governing and manipulating animals and natural phenomena. Thus, dragons began their “ambiguous collection” as an object of worship and a way to comprehend the inexplicable forces of nature. Over thousands of years of history, the dragon has become an integral part of Chinese culture. It represents the profound cultural heritage of the Chinese nation and possesses significant research value.

dragon in Chinese mythology

Given that the population of dragons is prosperous and they are fierce and terrifying, posing a constant threat to other animals and humans, associations and similar connections arising from dreams or conditioned reflexes naturally come into play. Therefore, the “Records of the Three Sovereigns” states, “The Flame Emperor, the Divine Farmer, of the Jiang surname, whose mother was Nuwa’s daughter, became the concubine of Shaohao and gave birth to the Flame Emperor by being impregnated by a divine dragon.” The “Huainanzi? Examining the Netherworld” states, “In ancient times, the Four Extremities were ruined, the Nine Continents were split, the sky did not cover all, and the earth was not all-encompassing. Fires burned fiercely without extinguishing, waters surged without subsiding, fierce beasts devoured the people, and predatory birds seized the weak and old. At that time, Nüwa smelted the Five Colored Stones to repair the heavens, cut off the legs of the giant turtle to establish the Four Extremities, killed the Black Dragon to save Jizhou, and piled up reed ash to stop the flooding.” Due to the high temperature period that occurred during the Late Pleistocene, there were primitive forest wildfires that burned fiercely without extinguishing, and due to glacier melting and rising sea levels, there was a persistent invasion of the vast ocean for thousands of years. Humanity was in a period of great challenges, and it coincided with the era of dragon dominance and hegemony over water. “Killing the Black Dragon to save Jizhou” thus became a wish and a necessary measure for human survival and competition. Hence, the legend of the Dragon Year being inauspicious and bringing calamities persists to this day.

In the “Classic of Mountains and Seas: Classic of the Great Wilderness in the North,” it is said, “Chiyou raised an army and attacked the Yellow Emperor, commanding the Yinglong to attack the fields of Jizhou. The Yinglong stored water, and Chiyou requested the Wind Earl and Rain Master, causing a great storm. The Yellow Emperor then summoned the celestial maiden Ba to stop the rain, and subsequently killed Chiyou.” This passage not only reflects the intimidating nature of dragons but also demonstrates how feudal rulers used people’s fears and worship to deify dragons and emperors.

Since the ancestors of the Huangdi clan group also revered dragons as their totem, the “Records of the Grand Historian: Book of the Celestial Officials” states, “Xuanyuan was of the Huang Dragon lineage,” thus further integrating the emperor and the dragon, enhancing the emperor’s majesty.

Afterwards, the deification of dragons and emperors as a single entity became more prevalent. For instance, the “Records of the Grand Historian: Annals of Gaozu” states, “Gaozu had a dignified and dragon-like appearance,” and the “Classic of Mountains and Seas: Inner Classic of the Sea” cites the “Kai Shi” commentary, which says, “After Gun died, for three years, he remained inseparable. His body was split open with a Wu knife and transformed into a yellow dragon.” The “Collected Accounts” states, “Yu exerted all his efforts to dig canals, guiding rivers and controlling mountains, with a yellow dragon dragging its tail in front and a black turtle carrying mud behind.”

In Volume Five of the “Records of Strange Stories,” it is written, “The palace of the Sea Dragon King… the sea water around it is turbid, but the water here is clear. Even without wind, the waves are several Zhang high, and boats dare not venture forward… In the middle of the night, from a distance, red light shines like the sun, stretching hundreds of Li and connecting with the sky. It is said that the palace of the Dragon King is located here.” Here, the primitive myth is combined with reality, forming a new secondary myth. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the mythology of dragons merged with novels, giving rise to mythological novels. The concept of dragons also permeated broader aspects of life and folk culture. For example, in the Tang Dynasty, Li Wei’s novel “Liuyi” tells the story of Liuyi delivering a letter to the Dragon Princess. Based on this story, the later works “Lingying Zhuan” from the end of the Tang Dynasty, “Yiluji,” “Xu Xuanguailu,” and “Boyizhi” from the Five Dynasties period, all developed similar mythological stories. In the Northern Song Dynasty, Li Fang and others compiled the “Extensive Records of the Taiping Era,” which mentions in Volume 418 the story of “Liang Sigong Ji,” saying, “In Zhenshe Lake, to the south of Dongting Mountain, there is a cave called Liudu, which is over a hundred feet deep… it is said to be the residence of the Seventh Daughter of the Dragon King of the Eastern Sea, who hides the Dragon Pearl. Numerous small dragons guard this pearl.” Thus, the title of Dragon King began to appear in ancient texts.

Perhaps inspired by stories like “Liuyi” and “Taiping Guangji,” Wu Cheng’en’s “Journey to the West” during the Ming Dynasty further developed the narrative. It includes episodes such as Sun Wukong causing chaos in the East Sea, where Dragon King Ao Guang is forced to surrender the Needle of the Sea’s Depth (Ruyi Jingu Bang); Wei Zheng dreaming of beheading the Dragon King of Jinghe; and the Dragon King of the Kingdom of Jiesai stealing the relic. The “Investiture of the Gods” mentions Nezha causing trouble in the sea, killing the young Dragon King Ao Bing and extracting dragon tendons to make a belt, as well as defeating the old Dragon King Ao Guang and plucking his dragon scales. This revolutionary transformation of significant historical importance displays contempt for the dragon, which symbolizes imperial authority, and essentially discredits and belittles feudal emperors. Consequently, dragons were further classified into benevolent and malevolent categories, reflecting the desires and grievances of the masses.

dragon pangu

Pangu is a mythical figure from Chinese legends. It is said that Pangu himself is a dragon. With the head of a dragon and the body of a snake, he gradually exhaled, creating the wind and rain, and blew out his breath, causing thunder and lightning. When he opened his eyes, it became daytime, and when he closed his eyes, it became nighttime.

After Pangu’s death, his bones transformed into mountains and forests, his body became rivers and seas, and his blood formed the rivers and valleys. His hair and fur turned into vegetation.

According to the legend, there were three heavenly dragons: a black dragon, a white dragon, and a yellow dragon. These nine dragons took turns incubating two dragon eggs. When the eggs hatched after 18,000 years, a divine being with horns on its head and wielding a giant axe emerged, known as Pangu. The older dragons were surprised by his different appearance, and one of them swished its tail, sending Pangu flying to the ground. Feeling stifled in the dim and chaotic surroundings, Pangu swung his axe and started cutting. As he chopped away, the clear Qi rose to the heavens, and the impure substances fell to the ground. The separation of the clear and turbid created a distinct and orderly world, which is the origin of Pangu’s act of separating the heavens and the earth.

Legend of Dragon Emperor and Heaven Emperor

The Dragon Emperor, also known as the Heavenly Emperor or the Jade Emperor, is believed to be the incarnation of Huangdi, the ancestral figure of the Chinese nation. According to the “Book of Enfeoffment” in the “Records of the Grand Historian,” Huangdi and the common people were mining copper ore in Shoushan (the First Mountain). They cast the extracted copper into a large bronze tripod and placed it at the foot of Jingshan (the Sacred Mountain). As the bronze tripod was being cast, a dragon with a long beard appeared to welcome Huangdi ascending to heaven.

Huangdi rode on the back of the dragon, and his ministers, as well as his wife and children, also climbed up one after another, totaling more than seventy people. However, there were still lower-ranking officials who couldn’t climb up and could only grab onto the dragon’s beard. Unable to bear the weight, the dragon’s beard broke, and the bow that Huangdi carried was also pulled down. The remaining officials could only hold onto the broken beard and the fallen bow, weeping in sorrow. After ascending to heaven, Huangdi became the Heavenly Emperor.

The Yellow Dragon is the Dragon Emperor, associated with the element of Earth and positioned in the center. It is the leader of the dragon clan and the ruler of the Heavenly Court in Taoist religious beliefs. Ancient texts from the Han Dynasty also mention: “The Yellow Dragon is the noblest of the four directions, the embodiment of divine spirits. It can be massive, subtle, hidden, bright, short, and long. It can appear and disappear. When a king possesses virtue and wisdom without meddling in the trivial, the Yellow Dragon responds with harmony and roams in ponds and lakes.” This description illustrates the image of the Yellow Dragon.

what does the Chinese dragon dance represent?

The symbolism of dragon dance primarily includes dispelling disasters, bringing good fortune, praying for rain, and celebrating bountiful harvests. The dragon is the totem of the Chinese nation, representing a spirit, a pursuit, a longing, and a blessing. Therefore, it can be said that dragon dance symbolizes the hardworking, brave, persevering, resilient, and enterprising spirit of the Chinese people.

son of Chinese dragon

During the Ming Dynasty, people associated the dragon with a prosperous family. In the evolution of its image, the dragon originated from a fusion of various grotesque animal forms. However, not all bizarre animal images merged into the dragon; alongside the formation and development of the dragon image, some peculiar animal forms also evolved and incorporated certain characteristics of the dragon. As a result, some people connected the two. In folklore, there has long been a belief in the dragon having nine offspring, but there is no precise record of what these nine offspring are. However, this curiosity of the “true dragon emperor” led to an outcome. It is said that during an early morning court session, Ming Xiaozong Zhu Youlang suddenly became curious and asked Li Dongyang, a renowned scholar and Minister of Rites, who also served as the Grand Secretary of the Imperial Academy, “I have heard about the dragon having nine offspring, but what are the names of these nine offspring?” Caught off guard, Li Dongyang could not provide an immediate answer. After the court session, he pondered and consulted several colleagues, combining folk legends and piecing together information until he finally produced a list, which he presented to the emperor. According to Li Dongyang’s list, the nine offspring of the dragon are:

Pafu: Fond of water, depicted as a carved beast on bridge columns.

Chaofeng: Adventurous in nature, represented by statues placed at the corners of palaces.

Yazhi: Inclined towards violence, with its form resembling a beast carved on the hilt of a knife.

Bi Xi: Strong and capable of carrying heavy objects on its back, as seen in stone turtles placed under stone tablets.

Jiaotu: Shaped like a conch shell and inclined to remain closed, often depicted with a necklace in its mouth.

Chiwen: Known for its appetite, represented by the beast head on the ridges of palaces.

Pudao: Fond of making noise, its head is used as the handle of large bells.

Suanni: Likes to crouch and sit, depicted as a lion-like creature under Buddhist statues.

Qiuniu: Fond of music, its form is carved on the upper end of the qin (a Chinese musical instrument) peg.

The concept of the dragon having nine offspring does not mean that dragons actually have precisely nine offspring. In traditional Chinese culture, the number nine is often used to signify abundance and holds a supreme position. Nine is a symbolic number, representing great significance, hence its use to describe the dragon’s offspring.

double dragon play ball

The Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl is a representation of two dragons frolicking or contending for a fiery pearl. Its origin can be traced back to the astronomical diagrams of planetary movements in Chinese astronomy, where the pearl evolved from the moon. Starting from the Western Han Dynasty, the Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl became a decorative motif associated with auspiciousness and celebration. It was often used in architectural paintings and adorned luxurious vessels.

The configuration of the Double Dragon depends on the area of decoration. If it is in a rectangular shape, the two dragons are symmetrically positioned on the left and right sides, appearing in a rowing posture. If it is in a square or circular shape, the two dragons are arranged diagonally, with one ascending and the other descending. Regardless of the arrangement, the fiery pearl is always in the middle, displaying a lively and dynamic momentum.

The Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl has a history dating back to the Pre-Qin period, spanning over three thousand years. In ancient Chinese mythology, the dragon pearl is considered the essence of dragons and the source of their cultivation. Therefore, in artistic expression, the competition between two dragons for the jade pearl symbolizes people’s pursuit of a better life.

According to legend, there was a deep pool in Tianchi Mountain where two green dragons practiced their cultivation. They were concerned about the well-being of the nearby people and frequently brought rain and wind to ensure a peaceful and prosperous life for them. The two dragons were beloved by the people. Tianchi was also the bathing place for heavenly maidens. Whenever the moon was shining brightly, the heavenly maidens would come here to bathe and frolic. Once, while the heavenly maidens were joyfully bathing in the pool, a hairy monster suddenly appeared and harassed them. They called for help, and upon hearing their cries, the two green dragons immediately donned armor and rushed to Tianchi. They saw a monstrous bear creating havoc, and the two dragons bravely fought together, ultimately defeating and capturing the bear monster.

The heavenly maidens informed the Jade Emperor of the rescue performed by the green dragons. Touched by their benevolent and righteous actions, the Jade Emperor took out a golden pearl from a gourd and presented it to the green dragons, urging them to continue their cultivation successfully. With only one golden pearl, neither dragon wanted to swallow it alone, so they passed it back and forth, resulting in a lively spectacle of shimmering golden light. Over time, this matter attracted the attention of the Jade Emperor, who dispatched the planet Venus to investigate.

After inspecting the situation, Venus observed the diligent cultivation, kind-heartedness, and loyalty of the two green dragons. He reported this to the Jade Emperor, who was also moved by their virtues. Consequently, the Jade Emperor presented another golden pearl to each dragon. They each swallowed a pearl and became celestial gods in charge of human destiny.

The common people, who never forgot the benevolence of the green dragons and admired their virtues, built temples to worship them throughout the four seasons. Over time, from the worship of the dragons, to the entertainment of dragon dances, and the transformation into auspicious and joyous dragon paintings, the Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl became a prevalent motif. The dragon dance and the painted pattern often portray the dragons in a rowing posture, depicting the ascending and descending movements and the exchange of the golden pearl between the two dragons. The motif of the Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl can be found in murals, dyeing and weaving, embroidery, carving, and other decorative crafts, making it a common sight in daily life.

The artistic form of the Double Dragon Playing with the Pearl, originating from folklore, carries the beautiful wishes of celebration, abundance, and auspiciousness.

Dragon Whisker Bead

The Dragon Whisker Bead, also known as Longxu Bead, is a auspicious ornament worn by ancient people that combines dragon whiskers and dragon pearls. Both the dragon whisker and dragon pearl have auspicious meanings, and the combination of the two in the Dragon Whisker Bead carries a deeper symbolism.

Dragon Whisker: According to the “Book of Enfeoffment” in the “Records of the Grand Historian,” the Dragon Emperor, also known as the Heavenly Emperor or the Jade Emperor, is believed to be the incarnation of Huangdi, the ancestral figure of the Chinese nation. When Huangdi ascended to heaven, a dragon with a long beard appeared to welcome him. Huangdi rode on the dragon’s back, and his ministers, along with his wife and children, also climbed up, totaling more than seventy people. As the dragon ascended to heaven, the remaining people grabbed onto the dragon’s beard, causing it to break under the weight. Half of the broken dragon whisker remained in the mortal realm. It is believed that dragon whisker-shaped ornaments have spirituality and can bless family members with safety, health, academic success, and career achievements.

Dragon Pearl: The Dragon Pearl refers to a pearl, which is produced in water and possesses a beautiful luster and form. Dragons are often depicted as the rulers of water in many legends and records. Therefore, people consider pearls to be dragon pearls. Pearls have been cherished and worn by people throughout history. In Chinese culture, pearls have been used medicinally for over 2,000 years. They are mentioned for their therapeutic effects in ancient medical books such as the “Records of Famous Physicians” from the Three Kingdoms period and the “Compendium of Materia Medica” from the Ming Dynasty. Modern medicine also acknowledges the calming, cooling, nourishing, eyesight-improving, and detoxifying properties of pearls.

Combination of Dragon Whisker and Dragon Pearl: The combination of dragon whisker and dragon pearl in the Dragon Whisker Bead carries a deeper meaning. While the dragon whisker brings auspicious blessings, according to folklore, it possesses spirituality and longs to return to the dragon’s body, taking away the auspicious blessings. On the other hand, dragons are known to be fond of dragon pearls. The purpose of the dragon pearl is to anchor the dragon whisker, keeping it in the mortal realm and preserving the auspicious blessings.

The Dragon Whisker Bead is not merely a product of feudal superstition. Like the dragon itself, it symbolizes the spirit of the Chinese nation and serves as a spiritual sustenance in people’s lives, reflecting the historical and cultural heritage of the Chinese people.

An increasing number of students and young people are paying attention to traditional Chinese culture. Although the Dragon Whisker Bead is an auspicious ornament worn by ancient people, its combination of whisker and pearl embodies a classic and fashionable design, coupled with its auspicious cultural significance, making it increasingly popular among people.

why do Chinese descendants of dragons?

Firstly, the dragon is a highly significant symbol and emblem in traditional Chinese culture, regarded as a sacred and auspicious symbol. In Chinese tradition, the dragon is considered the highest of animals, representing power, authority, and nobility. Therefore, calling oneself a “descendant of the dragon” implies a noble status and symbol of honor.

Secondly, the dragon has a long heritage and cultural legacy in Chinese history, dating back thousands of years. The dragon is extensively employed in various realms of Chinese culture, such as art, architecture, clothing, and cuisine, making it an essential component of Chinese culture. Thus, identifying as a “descendant of the dragon” also signifies pride and identification with Chinese culture and history.

Furthermore, identifying as a “descendant of the dragon” also represents reverence and respect for one’s ancestors. In ancient China, the dragon was considered a guardian deity and a bridge between heaven and earth, representing ancestral figures. Therefore, calling oneself a “descendant of the dragon” is also a commemoration and tribute to one’s ancestors.

In conclusion, the Chinese self-identification as “descendants of the dragon” is based on multiple reasons. This appellation signifies reverence and respect for the dragon, pride and identification with Chinese culture and history, as well as commemoration and respect for one’s ancestors.

Dragon Feng Shui

Dragons are mythical creatures with long bodies, scales, deer-like horns, claws, and the ability to fly in the air and swim in water. They are considered highly revered and symbolize authority and auspiciousness in Chinese culture. From the perspective of Feng Shui, dragons are part of the Four Divine Creatures (Dragon, Phoenix, Tortoise, and Qilin) in ancient China, with the dragon representing transformation, the phoenix representing order, the tortoise representing signs of good or bad fortune, and the qilin representing benevolence. As the leader among the Four Divine Creatures, the dragon has significant Feng Shui effects, including warding off negative energies, enhancing prosperity, attracting auspiciousness, and strengthening power.

Feng Shui Effects of Dragons

- Enhancing Wealth Luck

Placing a dragon above or on the sides of a fish tank in your home can enhance wealth luck. For optimal results, you can also place dragon-shaped ornaments in the owner’s wealth sector or the true north direction of the house.

- Warding Off Evil Spirits

Dragons symbolize authority and power, making them effective in warding off evil spirits. If you feel that your household’s luck is not prosperous or notice unusual occurrences, placing auspicious dragon decorations in favorable directions can dispel negative energies and ensure a flourishing home.

- Resolving Negative Energies

Dragons exude a regal aura and have a strong influence on impurities, yin energies, and dark forces. Placing Feng Shui dragons in your home can effectively resolve negative energies in areas near places with strong killing energies, such as slaughterhouses, cemeteries, funeral parlors, or in proximity to police stations, military bases, or prisons. Additionally, if there are buildings nearby with a strong solitary or oppressive atmosphere, such as temples or monasteries, placing a pair of Feng Shui dragons can help alleviate such influences. However, they are not suitable for piercing or road-killing energies.

- Balancing the White Tiger Position

If the White Tiger position is imbalanced, placing auspicious dragon ornaments on the Azure Dragon position can counteract the negative effects and prevent it from causing disturbances. For individuals such as company CEOs or private business owners who sense unusual activities or potential harm from subordinates, placing dragon-shaped mascots on the Azure Dragon position of their office desk is beneficial. If your house is compared to surrounding buildings and leans higher on the right side, placing a dragon-shaped auspicious item on the Azure Dragon position at home can help balance the energy. In cases where there is construction activity in the west-facing White Tiger position of your home during an unlucky year, placing a dragon-shaped auspicious item on the Azure Dragon position can be advantageous.

- Suppressing Enemies and Enhancing Mentor Luck

For those in the salaried class or working in government institutions, having adversaries or office politics can be detrimental. Dragons can mitigate conflicts and enhance mentor luck. If you find yourself surrounded by enemies and experiencing conflicts, placing a dragon-shaped auspicious item on the left side of your office desk (Azure Dragon position) can elevate your mentor luck and suppress negative influences, promoting career advancement and business development.

- Boosting Yang Energy

When there are fewer male members in the household or a lack of vitality and prosperity, you can use auspicious dragon ornaments in favorable positions to gather yang energy and enhance masculine qualities.

Materials and Sizes

Choosing the right materials for Feng Shui dragons is crucial, as dragons are regarded as noble and possess the ability to bring good fortune. It is advisable to select materials such as gold, bronze, jade, or ceramic to exude a sense of nobility. Furthermore, the depiction of dragons should convey a sense of dynamism and vitality, as stiffness and lack of movement will hinder their ability to manifest their dynamic energy. It is important to avoid a snake-like appearance.

Arrangement of Dragons

Dragons should be placed in harmony with water, as dragons thrive in water. Placing dragon decorations in areas without water, especially dry areas, may carry negative connotations such as “a dragon swimming in shallow water being toyed with by shrimp.” Therefore, it is advisable to place dragon-shaped ornaments in areas with water, preferably on both sides of a fish tank, to achieve optimal results.

The north direction is associated with abundant water energy, and dragons have an affinity for water. Therefore, placing Feng Shui dragons in the true north direction of your home is most suitable. Additionally, placing dragons on the left side is also favorable since, according to the Five Directions theory, the Azure Dragon represents the left side, and the White Tiger represents the right side.

If your house faces a river or the sea, you can use a pair of gray or black stone dragons placed on the windowsill or balcony railing, with their heads facing the ocean or river. This arrangement signifies the dragons venturing out to the sea, enhancing wealth luck. However, if the house faces a smelly drain or similar unpleasant surroundings, it is not advisable.

Precautions

When arranging dragon-shaped auspicious items, there are a few considerations to keep in mind:

- Avoid placing dragons facing bedrooms

While dragons are auspicious mythical creatures, their fierce appearance makes it unsuitable to face them towards bedrooms, especially if there are intimidating or aggressive-looking dragons. This arrangement is particularly unfavorable for children’s rooms.

- Avoid oversized dragons

If there is no water inside or outside the house, and you plan to place Feng Shui dragons with a fish tank, it is important to consider appropriate sizes. Placing oversized dragons on the walls of the fish tank can result in financial losses or unexpected disasters. Therefore, maintaining a proportional size between the Feng Shui dragons and the fish tank is crucial.

- Not recommended for those born in the Year of the Dog

From a zodiac perspective, the Dog clashes with the Dragon, so individuals born in the Year of the Dog are not advised to display dragon-shaped auspicious items, as it may bring them unfavorable effects.

- Pay attention to the number

The number of dragon decorations also holds significance. It is recommended to have one, two, or nine dragons. However, if there is a painting or artwork with nine dragons, it should have a central dragon as the main focus. Without a central dragon, it can create a chaotic atmosphere, leading to disputes and an unsettled home environment.

dragons and Buddhism

The relationship between dragons and Buddhism in China is complex. In the indigenous dragon worship in China, there was originally no worship of “dragon kings.” The worship of dragon kings was introduced after the spread of Buddhism. Prior to the Han Dynasty, there were only dragon deities and no “dragon kings.” However, after the Sui and Tang Dynasties, with the introduction of Buddhist beliefs, the worship of dragon kings became widespread in China. Scholars generally believe that the belief in dragon kings and dragon palaces originated in India and was introduced along with the spread of Buddhism. The long-lasting continuation of dragon culture in China can be attributed not only to the Confucian and Taoist traditions that fully inherited and promoted the belief in dragons as symbols of power and authority but also to the influence of the Buddhist concepts of “dragon palaces” and “dragon kings.”

In Buddhist scriptures, dragon kings are mentioned in various forms. For example, in the Lotus Sutra, there are references to eight dragon kings: Nanda Dragon King, Vedaśrī Dragon King, Sāgara Dragon King, Dhṛtividyut Dragon King, Sudarśana Dragon King, Anavatapta Dragon King, Mahānaṣa Dragon King, and Utpalaka Dragon King.

Did the indigenous dragon worship in China influence the worship of dragon kings in Buddhism, or did Buddhism influence the indigenous dragon worship? The relationship between the two is not entirely clear, but there are indications that the concept of dragons in Indian Buddhism was influenced by China and underwent further transformation to become “dragon kings.” As Buddhism spread eastward, the worship of dragon kings also spread to China. There are several reasons for this:

- Dragon worship has a long history in Chinese culture. Archaeological discoveries have revealed dragon depictions dating back thousands of years, such as the Longwangwa dragon sculpture found at the Cha’ahai site in Fuxin, Liaoning Province, which dates back approximately 7,000-8,000 years. Dragon worship was prevalent in China long before the earliest archaeological evidence of dragons in India.

- The earliest archaeological evidence of dragons in India, such as the paintings “Dragon Kings and Their Families” from the 1st century BCE and “Dragon Clan Worshiping the Bodhi Tree” from around the turn of the era, is more recent compared to the early dragon depictions found in China.

- In terms of written records, the earliest known Indian textual references to dragons are found in the works of the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna, who lived around the 2nd century CE. In contrast, Chinese records related to dragons predate those in India by a considerable margin. Dragon-related inscriptions and records can be found in oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty (around 3500 years ago), indicating the widespread worship of dragons in China.

- After the formation of Chinese dragon culture, it not only spread rapidly within the country but also quickly spread to other regions. The concept of dragons in Indian Buddhism likely originated from China. There were two possible transmission routes: one was through Tibet, as archaeological evidence suggests that cultural exchange between the Yellow River Basin and Tibet and its southern regions occurred as early as the Neolithic period. The transmission of dragon culture from China to Tibet and then to India is entirely plausible. The other transmission route was through the Silk Road in the Western Regions. The Central Plains dynasties had contact with the Western Regions over 3,000 years ago, and it is said that migrants from the Zhou Dynasty had already reached regions east of the Pamirs. After the fall of the Shang Dynasty, some Xia people migrated to northwestern regions, reaching Gansu and continuing westward to the Yarkand region in the Western Regions. The Dragon clan tribes that migrated to Yarkand became the ruling class of the Yarkand Kingdom during the Jin Dynasty, and they had the surname “Long” (龙). It is certain that they brought their dragon culture with them into the Western Regions.

- Ancient India did not originally have the concept of dragons. There is no dedicated word for “dragon” in the Sanskrit language; it was combined with the word for “elephant” to represent a dragon. After the introduction of Chinese dragons into India, dragon deities quickly replaced the deity Indra and became the dominant gods associated with storms and lightning. As a result, the word originally used for “elephant” came to represent “dragon” as well.

- In the “Records of the Western Regions” (also known as “Great Tang Records on the Western Regions”), there are about 20 dragon legends mentioned, with five from the Western Regions, five from northern India, and ten from central India. However, there is no mention of any dragon legends from southern India. The dragon legends from Kucha and Khotan in the Western Regions are similar to ancient Chinese dragon legends, including stories of riding dragons and dragons mating with women to produce dragon offspring. These legends are unrelated to Buddhism. On the other hand, the dragon myths and legends from the regions south of the Ganges mentioned in the “Records of the Western Regions” are connected to Buddhist figures. This suggests that the transmission of Chinese dragon culture to India likely occurred through the Western Regions.