The Tang dynasty is among the first imperial dynasties of China. It was established by the Li family after the fall of the Sui dynasty. It reigned from 618-907 with a brief interruption by the Wu Zhou dynasty that took over from 690-705. Its capital was Changian which is now known as Xi’an.

The dynasty started with a population of 50 million people and it grew to 80 million by the end of its reign. At that time its capital was the most populated in the world. The tang dynasty was considered a great era in which many great things happened.

what is the Tang Dynasty?

The Tang Dynasty was a prominent dynasty in Chinese history that ruled from 618 to 907 AD. It is considered one of the most prosperous and culturally vibrant periods in China. The Tang Dynasty was founded by Emperor Gaozu, also known as Li Yuan, who established the dynasty’s capital in Chang’an (present-day Xi’an).

During the Tang Dynasty, China experienced a golden age of literature, art, and technological advancements. It was a period of great territorial expansion and international influence, with the empire extending its reach along the Silk Road and engaging in diplomatic relations with neighboring countries and regions.

The Tang Dynasty is known for its strong centralized government, efficient bureaucracy, and legal reforms. It implemented the civil service examination system to recruit government officials based on merit rather than aristocratic background. This system promoted social mobility and intellectual development, contributing to the dynasty’s cultural achievements.

The Tang Dynasty saw advancements in various fields, including poetry, painting, calligraphy, music, and ceramics. Some of the most renowned poets, such as Li Bai and Du Fu, emerged during this period, leaving a lasting impact on Chinese literature. Tang art and architecture, characterized by grand palaces, Buddhist cave temples, and exquisite tomb figurines, also flourished.

Despite its achievements, the Tang Dynasty faced challenges towards the end of its reign, including political instability, rebellions, and external threats. In 907 AD, the dynasty was overthrown by a military revolt, leading to the fragmentation of China and the beginning of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

why was it called the Tang Dynasty?

The naming of the Tang Dynasty is associated with Li Yuan. Li Yuan was granted the title of Duke of Tang (唐国公, Táng Guógōng), and therefore, the dynasty was named “唐” (Tang) after his noble title. Historians widely agree that the choice of this name was due to Li Yuan’s title of Duke of Tang. Li Yuan received the title of Duke of Tang at the age of seven. Later, Li Yuan and his sons rebelled in Taiyuan, captured Chang’an, overthrew the Sui Dynasty, and established a new dynasty—the Tang Dynasty. As Li Yuan had inherited the title of Duke of Tang, it was only natural that, upon assuming the imperial title, the dynasty would be named “唐” (Tang).

In English translation, “唐朝” (Tang Dynasty) can be rendered as the “Tang Dynasty,” “唐国公” (Duke of Tang) as “Duke of Tang,” and “唐” (Tang) as “Tang.”

how was the Tang Dynasty founded?

In the late period of the Sui Dynasty, due to a series of policy mistakes by Emperor Yang of Sui, large-scale rebellions broke out across the country. In the 11th year of the Daye era (615), Emperor Yang appointed Li Yuan as the Ambassador to Shanxi and Hedong to appease the region. Soon after, he was appointed as the Garrison Commander of Taiyuan to defend against the Turks and suppress peasant uprisings in present-day Shanxi Province.

At that time, the Sui regime was on the verge of collapse, with the ruling class experiencing repeated divisions, and armed landlords and rebel armies scattered throughout the country. Li Yuan, who had ambitious aspirations, began contemplating the idea of seizing power after his transfer to Taiyuan. His advisors, Pei Ji, Liu Wenjing, and his second son, Li Shimin, all suggested that he rise up and seize the opportunity. In the 12th year of the Daye era (617 AD), the peasant uprisings gained the advantage nationwide, and the Sui Dynasty was no longer able to concentrate its forces effectively to combat the various armed groups. Li Yuan deemed the timing ripe and, in May of the following year, he killed Deputy Garrison Commander Wang Wei and Gao Junya in Taiyuan, officially announcing his rebellion.

In July, Li Yuan, along with his eldest son Jiancheng and second son Shimin, led their troops southward, capturing Huoyi (present-day Huo County, Shanxi) and crossing the Yellow River, advancing southwestward. At that time, Emperor Yang of Sui was far away in Jiangdu (present-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu), and the Sui forces in the Guannei region were weak, with the Wagang Army and Wang Shichong engaged in fierce battles and unable to turn their attention to the west. As a result, the Li family advanced rapidly, and in November, they breached Chang’an. Shortly after Li Yuan entered Chang’an, he proclaimed Emperor Yang of Sui as the Retired Emperor and enthroned Yang You, the grandson of Emperor Yang, as the new emperor, establishing the Yanping era, known as Emperor Gong of Sui. Li Yuan assumed the position of Grand Chancellor and was granted the title of Prince of Tang. In the 14th year of the Daye era (618 AD), Emperor Yang of Sui was killed in Jiangdu. In May, Li Yuan forced Emperor Gong to abdicate, proclaimed himself emperor, and established the Tang Dynasty with Chang’an as its capital. He changed the era name to Wude. Li Yuan and his son, Emperor Taizong, spent 10 years unifying the separatist forces across the country and unifying China. They then turned their attention to the north, defeating the power of the Turks and expanding their influence into Central Asia. This was the pinnacle period in Chinese history, known as the Tang Dynasty.

What Is the Tang Dynasty Most Known For?

The Tang dynasty is considered to have been the greatest imperial dynasty know in Ancient Chinese history. Their reputation surpassed them internationally and went beyond their cities to almost all of Asia. The dynasty was famous for many things, starting from its palaces, cities, and territorial expansions. It is also considered a great era when Chinese culture, literature, art, religion, and foreign trade flourished. Around the dynasty’s reign was when China was considered one of the most powerful countries in the world.

Famous for its government, the Tang Dynasty was ruled by great emperors whose rule made the dynasty the great era it was. They lay down the groundwork for the policies that are still used in China today. They reformed the military and government by having direct control over the armies, labor, and grain control. This dynasty had the only female ruler known in Chinese history. She laid the foundation that led to China being the most prosperous country in the world at the time.

This dynasty is also known for its great advancements in technology and innovation. This included advancements in medicine, architecture, science, and literature. Its most famous invention was woodblock printing, which allowed the mass production of books, hence improving literature. Another great invention was gun powder, which was perfected over the years but mostly used for fireworks at the time. Other great advancements were gas stoves and air conditioning.

The Tang dynasty is also famous for its flourishing literature and culture. It was the time when poetry was included in Chinese culture. People were encouraged to express their creativity. Thanks to woodblock printing, a lot of poems, short stories, and other literary works and encyclopedias were made. This improved the literacy of the people. Some of the most famous poets and painters came from this time.

Other than that, the dynasty was known for the popularity of Buddhism due to its widespread practice at the time. Its popularity however decreased towards the end of the dynasty’s reign. Around the time when China went into chaos.

List of Emperors of Tang Dynasty.

As mentioned, the Tang dynasty was established by the Li family. Its reign was overseen by great emperors, with the four notable ones in particular. Taizong, the second emperor when the dynasty was established, his successor Gaozong, Gaozong’s wife Wu Zetian, and Xuanzong, the last emperor of the dynasty. The following is the full list of emperors that ruled during the 1st and 2nd reign of the Tang dynasty:

- Gaozu (Li Yuan) – the first emperor of the Tang Dynasty. He reigned from June 18, 618-September 4, 626.

- Taizong (Li Shimin) – the second emperor famed for his reformation of the government, military, education, and religion. He reigned from September 4, 626-July 10, 649.

- Gaozong (Li Zhi) – ruled alongside his wife Empress Consort Wu Zetian who acted as a regent. His rule was from July 15, 649-December 27, 683. The wife continued to rule as a regent until 705.

- Zhongzong (Li Xian/Zhe) – son of Gaozong and Wu Zetian. Ruled for less than two months, January 3, and 684-February 26, 684, before he was dismissed by his mother. He came back into power on February 23, 705-July 3, 710. This was after tang had won back power from the Wu Zhou dynasty, and her mother was no longer a regent.

- Ruizong (Li Dan) – another son of Gaozong and Wu Zetian. He had a long rule of six years, February 27, 684-October 8, 690, before he was also dismissed by his mother. He also came back into power on July 25, 710-September 8, 712, after the overthrowing of the Wu Zhou.

- Shang (Li Chongmao) – reigned in between the second reign of the two brothers Ruizong and Zhongzong. His rule lasted between July 8, 710-July 25, 710.

- Xuanzong (Li Longji) – considered to be one of the greatest rulers before the fall of the dynasty. He ruled between September 8, 712-August 8, 756.

The other emperors who ruled after Xuanzong are as follows:

- Suzong (Li Heng) – from August 12, 756-May 16, 762.

- Daizong (Li Yu) – from May18, 762-May23, 779.

- Dezong (Li Kuo) – June 12, 79-February 25, 805.

- Shunzong (Li Song) – February 28, 805-August 31, 805.

- Xianzong (Li Chun) – September 5, 805-February 14, 820.

- Muzong (Li Heng) – February 20, 820-February 25, 824.

- Jingzong (Li Zhan) – February 29, 824-January 9, 827.

- Wenzong (Li Ang) – January 13, 827-February 10, 840.

- Wuzong (Li Yan) – February 20, 840-April 22, 846.

- Xuanzong (Li Chen) – April 25, 846-September 7, 859.

- Yizong (Li Chui) – September 13, 859-August 15, 873.

- Xizong (Li Xuan) – August 16, 873-April 20, 888.

- Zhaozong (Li Ye) – first reign April 20, 888-December 1, 900. Second reign January 24, 901-September 22, 904.

- Zhaxuan (Li Zhu) – September 26, 904-May 12, 907

When Did the Tang Dynasty Start and End?

The beginning of the Tang Dynasty was a result of the rebellion against the Sui Dynasty that came before it. The last two kings, Wen and his son Yang led the government to bankruptcy and immense debt. The Sui dynasty finally fell when Yan was assassinated by Yuwen Huaji, his chancellor, and Li-Yuan, a popular general of the army. Li Yuan was at the time the Duke of Tang. He rose in rebellion to take control and become the emperor Gaozu in 618 CE, thereby establishing the Tang Dynasty. Under the reign of the Tang dynasty, great rulers like Taizong, Wu Zetian, and Xuanzong, led China to become one of the most prosperous countries at the time.

The fall of the Tang Dynasty began during the An Lushan rebellion that was caused due to Xuanzong’s gradual neglect of duty. Even after that rebellion was ended and respect restored to the throne, the dynasty never went back to its original glory. The final blow was the Huan Chao rebellion which completely weakened the dynasty. Its reign finally came to an end with the assassination of the last Tang emperor Ai, by Zhe Wen in 907.

Tang Dynasty Achievements Timeline.

The Tang Dynasty was among the greatest imperial dynasties in Ancient China. It, therefore, had many notable milestones throughout its reign. The following is a summary of the Tang Dynasty timeline and some of its most notable events:

- 618 – Gaozu rises to power establishing Tang Dynasty as the first emperor.

- 626-649 – the reign of one of the greatest Tang emperors, Taizong, and the development of woodblock printing.

- 649 – beginning of the reign of Gaozong and his wife Wu Zetian.

- 667 – Tang dynasty army is successful in taking over the Goguryeo, Pyongyang’s capital in North Korea.

- 668 – Fall of the Goguryeo kingdom after the attack by the Tang Dynasty.

- 675 – carving of the Buddhist cave at Longmen Grottoes in China.

- 683-704 – the reign of the first and only female ruler, Wu Zetian after the husband’s reign.

- 712-756 – the 7th Tang emperor Xuanzong makes Taoism an official religion of China.

- 755 – the occurrence of the An Lushan rebellion against Xuanzong.

- 762-779 – the reign of emperor Daizong who put an end to the An Lushan rebellion.

- 806-820 – the reign of Xianzong who restored respect to the Tang Dynasty throne.

- 842-845 – the persecution of the Buddhist monks and the monasteries in China.

- 859-873 – China suffers a severe drought and famine period.

- 873-888 – the rise of the Huang Chao rebellion that topples and weakens the Tang Dynasty.

- 904 – the assassination of emperor Zhaozong by warlord Zhe Wen.

- 907 – the assassination of Ai, the last emperor of the Tang Dynasty, by Zhe Wen. marking the end of the Tang Dynasty.

Why Tang Dynasty Was Golden Age.

The Tang Dynasty was considered a golden age due to its successful ruling that led to the flourishing of China, expanding its influence to different parts of inner Asia. The impressive government and administration led China to be an educated and wealthy realm by the standards of that age.

To begin with, Chinese culture flourished most during the reign of the Tang dynasty. The dynasty was even said to have had a great cultural influence over neighboring East Asian countries like Korea and Japan. It was also said to be the greatest age of Chinese poetry, producing two of the most famous Chinese poets in history, Du Fu and Li Bai. Famous painters like Zhang Fang and Zhou Xuan also came from this era.

Additionally, during the tang dynasty’s reign, there were notable innovations like woodblock printing. The Tang dynasty is a famed era known for many achievements. Its successful reformation and advancements that led to the flowering of Chinese art and culture, is what made this dynasty’s reign the best era of that time.

How Did the Tang Dynasty Reunify China?

After the fall of the Western Jin Dynasty in 316, China was divided for centuries. Even when the Tang Dynasty rose to power in 618, it initially only ruled over Guanzhong. The central, northeast, and south plain were still being controlled by warlords who commanded hundreds of thousands of troops at the time.

To enforce order, the Tang Dynasty set up 43 regional military commands spread out across China but concentrated around capitals. The 43 commands consisted of 600 militia units each having 800-1200 men aged 21-60 years. Adding to that, the dynasty also had a central army made up of princely guards who were sons of elite families. The army was located in the capital and used for single campaigns, that delivered a rapid force ensuring victory. It wasn’t until the five-year campaign by Tang princes Li Jiancheng and Li Shimin (Taizong), that China was finally reunified.

Why Did the Tang Dynasty End?

The beginning of the Tang Dynasty was characterized by success and reformation that restored the glory of China. This was under the great leadership of the like of Taizong, Wu Zetian, and Xuanzong. Their success was based on the control they had on the military, labor, and grain control. Additionally, they were fair leaders, who appointed people on merit and took their responsibilities seriously.

Under Xuanzong’s rule, however, the dynasty began to fall when he began neglecting his duties as emperor and promoting people without any merit. This led to the An Lushan Rebellion, arranged by a general named An Lushan. Xuanzong fled and later abdicated the throne for his son Suzong, who was unable to stop the rebellion. His son, Daizong was the one who managed to end the rebellion. It was, however, his great-grandson Xianzong who managed to restore respect to the throne.

Still, the Tang dynasty was never the same after the An Lushan rebellion, with one ineffective leader after another taking the throne. The great dynasty finally came to an end when a warlord named Zhe Wen assassinated the last Tang emperor Ai at 15 years, end. This left China divided where warlords and their families claimed territories leading to the period of the five dynasties and ten kingdoms in 907. That is until the rise of the Song dynasty in 960.

The Tang Dynasty was among the greatest imperial dynasties ever known in the history of Ancient China. Still, like many other dynasties before and after it, its fall was a result of tyrants and ineffective leaders who neglected their duty to their people.

Tang Dynasty system of government

The political system of the Tang Dynasty: the Three Departments and Six Ministries system. The distinctive feature of the Three Departments system in the Tang Dynasty was that it soon transitioned to the Two Departments and One Department system. In order to control the power of the chancellor, the emperor gradually involved officials with relatively lower qualifications in the government affairs, who actually exercised the power of the chancellor. However, due to the lack of a formal system for the chancellor, it was easier to control.

The positions of the Chancellor of the Imperial Secretariat, Palace Attendants, and Prefect of the Palace Secretariat became honorary titles, while the actual chancellor became a temporary position.

The highest-ranking officials in the Three Departments system, such as “Pingzhangshi” and “Tongzhongshu Menxia Sanpin,” were often held by officials from other positions, but granted the title of chancellor as an additional honor. (New Book of Tang, Volume 46, Records of Officials)

During the eighth year of the Zhenguan reign of Emperor Taizong, when the Palace Attendant Li Jing resigned from the position of chancellor due to illness, Emperor Taizong disagreed and requested him to “quickly recover and come to the Imperial Secretariat as Pingzhangshi every three or five days.” The title of “Pingzhangshi” originated from this. In the first year of Emperor Gaozong’s Yongchun reign, officials (such as Guo Daiju, the Yellow Gate Attendant, and Cen Changqian, the Minister of War) were granted the additional title of “Tongzhongshu Menxia Pingzhangshi” to become chancellors.

In the fourth year of the Changxing reign, due to naming taboo (related to the father’s name of Murong Yanzhao), the title was temporarily changed to “Tongzhongshu Menxia Erpin” since the position of Shangshu Pushe was a second-rank position.

In the 17th year of the Zhenguan reign, Xiao Yu and Li Ji were granted the title of “Tongzhongshu Menxia Sanpin” (the third rank of the Imperial Secretariat), as the positions of Shizhong and Zhongshu Ling were both of the third rank. The title of “Tongzhongshu Menxia Sanpin” originated from this. After Emperor Gaozong, it became a requirement for chancellors to hold the additional title of “Tongzhongshu Menxia Sanpin.” Without this title, even if one held the position of Zhongshu Ling, they could not be considered a chancellor, and the same applied to those of higher rank (excluding those with the titles of the Three Excellencies and Three Masters).

The Three Departments shared the same office space and handled discussions and administrative affairs. The functions of the Three Departments gradually merged and became more integrated.

To facilitate coordination among the Three Departments, the heads of the Three Departments regularly held meetings in the Zhengshi Hall of the Menxia Province. Starting from the Wude period, the Zhongshu and Menxia Departments convened their discussions in the Zhengshi Hall, which was located in the Menxia Province.

During the reign of Emperor Gaozong, “Pei Yan was promoted from Shizhong to Zhongshu Ling, and the Zhengshi Hall was moved to the Zhongshu Province.” This solidified the central position of the Zhongshu Province. In the 11th year of the Kaiyuan reign, Zhongshu Ling Zhang Shuo proposed changing the name of the Zhengshi Hall to Zhongshu Menxia, and the seal of the Zhengshi Hall was also changed to the seal of the Zhongshu Menxia. Subsequently, the departments of Personnel, Secretariat, Defense, Revenue, and Punishment-Ceremonial were established. From then on, the Zhongshu Menxia officially became the administrative agency for chancellors.

The Shangshu Province was temporarily renamed Wenchang Tai, Dutai, and Zhongtai during the Tang Dynasty but later reverted to its original name.

The Zhongshu Province was temporarily renamed Xitai, Fengge, and Ziwai Province but later reverted to its original name.

The Menxia Province was temporarily renamed Dongtai, Luantai, and Huangmen Province but later reverted to its original name.

tang dynasty economic system

The economy of the Tang Dynasty refers to the economic development in the regions of the Central Plains, Jiangnan, Sichuan, Lingnan, and other areas under the rule of the Tang Empire from the 7th century to the early 10th century. This period is generally considered a crucial transition from ancient to medieval China in terms of economic development.

The Tang Dynasty was a prosperous and powerful dynasty that witnessed significant economic growth and expansion. The turmoil at the end of the Sui Dynasty led to a large amount of unclaimed land, which allowed for the continued implementation of the equal-field system (known as “juntian zhi”). This system, which allocated land based on population, played a significant role in stabilizing agriculture. Additionally, the economy of the Jiangnan region, which had been steadily developing since the Six Dynasties period, demonstrated a trend of surpassing the Yellow River Basin. The Tang Dynasty’s control over both the northern and southern economies contributed to its economic strength. Even after the An Lushan Rebellion, despite the devastation in North China, the Tang government could rely on the economic resources of Jiangnan to sustain its recovery.

Since the beginning of the Sui and Tang Dynasties, China’s economy entered a higher stage of development.

Equal-field System:

The equal-field system, which originated during the Northern Wei Dynasty and continued until the middle period of the Tang Dynasty, was a land distribution system based on population. It allocated land to individuals for a certain number of years, after which the land would either remain with the user or be returned to the government upon their death. By the middle period of the Tang Dynasty, land consolidation became increasingly severe, making it impossible to carry out land redistribution. As a result, the equal-field system was completely dismantled during the reign of Emperor Dezong. The implementation of the equal-field system affirmed land ownership and possession, reduced disputes over land ownership, and facilitated the reclamation of abandoned land. It played a positive role in the recovery and development of agricultural production. Moreover, the equal-field system helped peasants break free from the control of powerful clans and gradually transformed them into state-controlled households, increasing the number of self-cultivating small farmers under government control. This ensured the source of taxes and further strengthened the centralized autocracy.

Tax and Labor Service System:

The tax and labor service system, known as the “zuyong diao zhi,” was another taxation system implemented during the Tang Dynasty. It primarily involved the collection of grains, cloth, or compulsory labor for the government and was based on the implementation of the equal-field system. The term “zuyong” referred to the annual grain tribute paid by adult males, “diao” referred to the payment of a specific amount of silk or cloth, and “yong” referred to the option of providing silk or cloth in place of labor service during the period of conscription. According to the regulations, all individuals under the equal-field system, regardless of the size of their land, were required to pay a fixed amount of taxes and perform specific labor duties. The tax and labor service system relied on the successful implementation of the equal-field system. However, as the population increased during the later period of the Tang Dynasty, coupled with widespread land consolidation, the government could no longer implement the equal-field system effectively. Many peasant households were unable to afford the fixed taxes and fled as a result. After the An Lushan Rebellion, the burden on the imperial court increased significantly, leading to the implementation of Yang Yan’s “liangshui” (double taxation) system, which primarily collected money and silver as taxes. This will be discussed in detail below.

Double Taxation System:

The “Double Taxation System,” also known as the “liangshui,” was a tax reform implemented during the reign of Emperor Dezong in the Tang Dynasty, suggested by the Chancellor Yang Yan. It consolidated various taxes, including the rent-in-kind, corvée labor, and miscellaneous levies, into a unified taxation system. It shifted the primary basis of taxation from the household-based system to one based on land and assets. Due to the collection being conducted in two seasons, summer and autumn, it became known as the Double Taxation System. This reform represented a comprehensive overhaul of the contemporary fiscal and labor system.

tang dynasty coins(Currency of Tang Dynasty)

During the Tang Dynasty, silver was not yet widely circulated as a currency, and silver notes had not yet appeared. Instead, people primarily used copper coins or silk and textiles as currency, a system known as “qianbei jianxing,” meaning the coexistence of coinage and fabric as mediums of exchange.

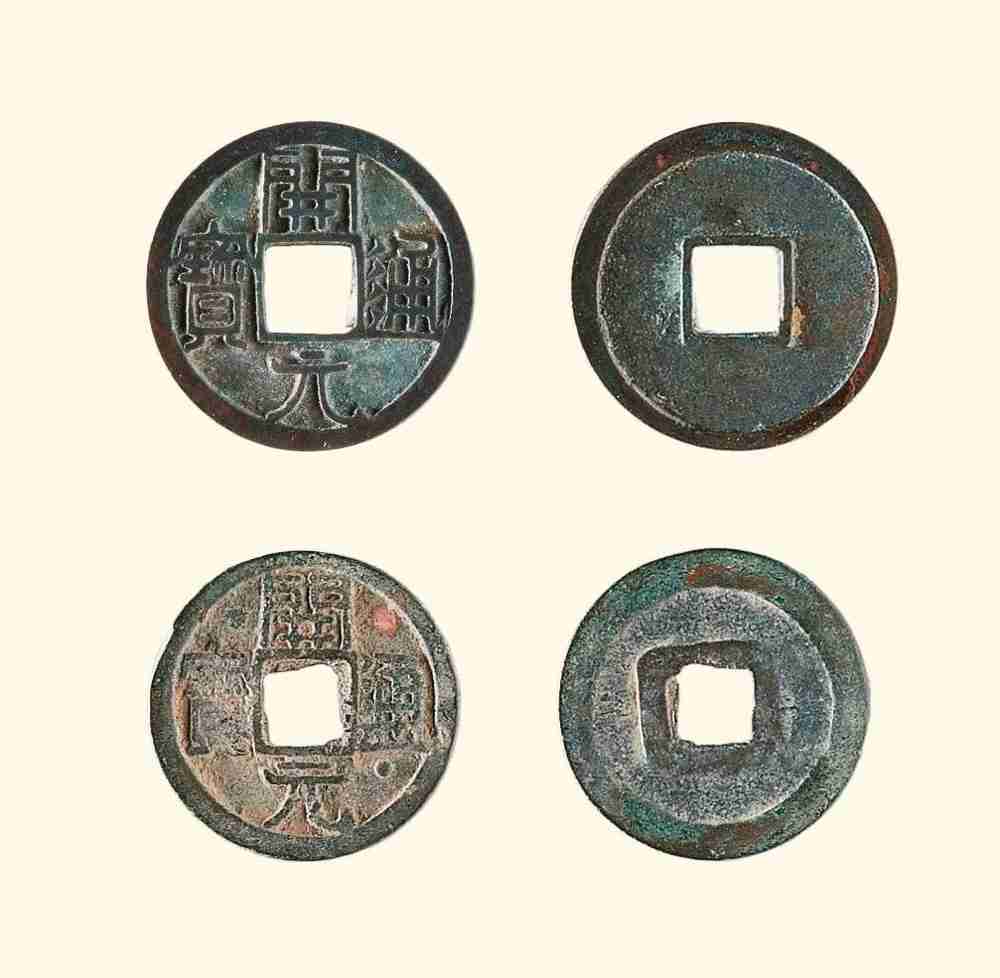

After the establishment of the Tang Dynasty, a coinage policy system was introduced. In the fourth year of the Wude era (621 AD), the “wuzhu” coins were abolished, and the “kaiyuan tongbao” coins were introduced. These coins had a diameter of eight fen and weighed 2.4 zhu, with ten coins equaling one wen and one thousand wen equaling six jin four liang. This solidified the legal tender status of the state’s coinage. Additionally, the Tang Dynasty inherited the tradition of using silk and textiles as currency from the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, implementing a currency system known as “qianbei jianxing,” where “qian” referred to copper coins and “bei” encompassed various types of silk fabric, including brocade, embroidery, damask, satin, and other types. This system essentially constituted a diverse currency system that combined both commodity and metallic currencies.

The Tang Dynasty abolished the widely circulated “wuzhu” coins that had been in use since the time of Emperor Wu of Han and began using the “kaiyuan tongbao” coins. The inscription “kaiyuan tongbao” on the coins was written by the renowned calligrapher Ouyang Xun, featuring elegant and upright lettering. These coins were highly appreciated and sought after by collectors throughout history. As the Tang Dynasty represented a prosperous era in ancient China, the “kaiyuan tongbao” coins were imbued with the meaning of warding off evil and bringing fortune.

In addition to the “kaiyuan tongbao,” other coin types were issued during the Tang Dynasty, such as the “qianyuan zhongbao” coins during the reign of Emperor Suzong, the “dali yuanbao” coins during the reign of Emperor Daizong (although no historical records mention them, existing specimens do), as well as the “de yi yuanbao” and “shun tian yuanbao” coins minted by An Lushan.

The “qianyuan zhongbao” coins were first minted in the first year of the Qianyuan era (758 AD) during the reign of Emperor Suzong. One “qianyuan zhongbao” was equivalent to ten “kaiyuan tongbao” coins. The early coins had a distinct and robust design, while later ones became smaller and lighter. Among them, the copper prototype coins were the earliest known copper prototypes discovered to date and featured designs of stars, moons, auspicious clouds, and auspicious patterns on the reverse side.

The “dali yuanbao” coins were local mintings in the northwest region during the reign of Emperor Daizong (766-779 AD). They were crudely made with a dull copper color and inscribed in clerical script with the four characters “dali yuanbao.” There were two sizes, large and small.

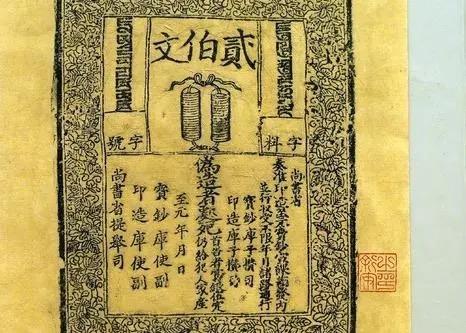

During the Tang Dynasty, urban centers witnessed the emergence of “guifang” (money storage agencies) and “feiqian” (flying money). “Guifang” facilitated the deposit and transfer of money and goods, allowing customers to send payments using written vouchers (similar to checks). These developments demonstrate the prosperity of commerce during the mid-Tang period. However, towards the end of the Tang Dynasty, due to events such as the Huang Chao Rebellion and the rise of regional military governors, the population declined sharply, and the scale of socio-economic activity never reached the level of the prosperous Kaiyuan era.

With the further development of commerce, in the later period of the Tang Dynasty, “didian” (warehouses) widely appeared, providing storage and wholesale services for merchants, as well as “guifang” (money depositories), which undertook the management of merchants’ funds. Merchants could deposit their funds with the “guifang” by paying a certain cashier fee and then withdraw them using vouchers. Additionally, a form of credit certificate emerged in the later period of the Tang Dynasty, known as “bianhuan” or “feiqian” (flying money). Traveling merchants could pay money to relevant institutions and merchants in the capital, obtain semi-detached vouchers, and redeem them for cash upon returning to their respective regions. The emergence of flying money provided convenience for merchants engaged in long-distance trade to the capital. All these developments were closely tied to the growth of the commercial economy during the Tang Dynasty.

tribute system tang dynasty

The Tang Dynasty’s “centrality diplomacy” had become quite sophisticated. All countries that had diplomatic relations with the Tang Dynasty were incorporated into its diplomatic system.

In the Tang Dynasty’s diplomatic system, countries were ranked, and the corresponding reception and treatment were based on these ranks. The specialized diplomatic department in the Tang Dynasty was called the Honglu Si (Ministry of Rites), headed by the Honglu Qing (Minister of Rites) and assisted by the Shaoqing (Assistant Minister of Rites), who had diplomatic missions.

The enthronement of foreign political leaders was the prerogative of the Chinese emperor, and the officials such as the Honglu Qing were the executors who participated in the coronation ceremonies of foreign heads of state, expressing the political stance of the Chinese emperor. The Dianke Shu under the jurisdiction of the Honglu Si was responsible for receiving foreign guests. “For all tribute missions, banquets, escorting, and welcoming, their respective roles were assigned according to their ranks. As for tribal leaders who came to pay homage, they were accommodated and treated with appropriate rituals.” Rank was evidently a crucial factor. Specifically, “those ranked third or higher were assigned to the third category, those ranked fourth or fifth were assigned to the fourth category, and those ranked sixth or lower were assigned to the fifth category.” Foreign envoys visiting China for the first time might not have an official rank, but the Tang Dynasty made arrangements accordingly, with different levels of treatment based on their status. This was a characteristic of the hierarchical system of that era.

It was quite common for foreign leaders to receive official positions from the Tang Dynasty, which was a rule mutually observed by both sides. Taking Ashina Simo as an example, he was a Turkic leader holding the position of “Jiabitiqin” within the Eastern Turkic Khanate, without military authority. He visited the Tang Dynasty multiple times, and Emperor Taizong of Tang conferred upon him the title of “Huaihua Junwang” (Prince of Huaihua County).

In the fourth year of the Zhenguan reign (630 AD), Emperor Taizong appointed him as “Right Wuhou Grand General, Commander of Huazhou,” and in May, he was further enfeoffed as “Huaixia Junwang” (Prince of Huaixia County). The military rank of Wuhou was the third highest, while the noble rank of Junwang was the first. Many enfeoffments were carried out in a hereditary manner, such as the King of Silla being enfeoffed as the Prince of Lelang, the King of Baekje as the Prince of Daifang, and the King of Goguryeo as the Prince of Liaodong.

Most countries that had diplomatic relations with the Tang Dynasty were vassal states and paid tribute to the Tang Dynasty. Receiving an official position from the Tang Dynasty was likely one of the aspects of their diplomatic interactions. Historical records referred to these Tang Dynasty’s diplomatic partner countries as “foreign subjects.” Since the Tang Dynasty dominated diplomatic affairs and determined the conditions and treatment for countries engaging with China, the only possibility for these countries was to accept this arrangement. The notion of formal equality in diplomatic exchanges did not exist.

Ancient diplomacy adhered to the principle of power in a transparent and unapologetic manner. One can understand the fundamental inequality in international relations by examining the ancient Persian Empire’s enduring relief sculpture of “The Tribute Bearer.” In conflicts between evenly matched major powers, the choices for small countries became increasingly difficult, forcing them to navigate cautiously. The prolonged war between the Western Han Dynasty and the Xiongnu led many small countries to switch their allegiance between the two powers. The King of Loulan, for instance, appealed to Emperor Wu of Han, stating, “A small country caught between larger nations cannot survive without submitting to one of them.” This plea exemplifies the predicament faced by small countries. When engaging with major powers, small countries do not seek equal footing but rather pursue practical interests.

The term “tribute” may suggest subordinate states making offerings, creating a clear master-servant relationship in politics. However, recent research indicates that tribute should be viewed as economic relations, leading scholars to refer to it as “tribute trade.”

The Tang Dynasty had unique linguistic descriptions for this tribute trade. The offering party was referred to as the “donating side,” with specific “donations” such as prized horses, war elephants, and lions. The Tang Dynasty had specific regulations outlining the procedures and methods for receiving and handling these offerings. If the items were medicinal or food products, they would be inspected, packaged, and sealed by border counties upon entering Tang territory. They would then be handed over to the envoys, with a report sent to the Ministry of Rites. Once the Ministry of Rites confirmed the validity, the Ministry would inform the Ministry of Revenue and the market management department, dispatching officials to inspect the tribute goods and determine their value. Subsequently, a report would be submitted and forwarded to the imperial court, where decisions regarding introductions, banquets, and other matters were made according to the court’s instructions. When the envoys returned to their countries (referred to as “reversion to foreign lands”), they were rewarded (“gifts varied by rank”). The rewards took place in the court, with officials from the Bureau of Guests guiding the envoys in receiving the rewards and instructing them on proper ceremonial etiquette. The previous valuation of the tribute items played a causal role in the final reward stage, as the emperor’s rewards were based on the value of the donated goods. Although it was not labeled as a trade, it essentially functioned as such.

During the Tang Dynasty, the emperor’s bestowed gifts to foreign envoys were primarily textiles, which constituted the true meaning of “gifts.” However, these gifts were categorized as either “internal” or “external.” For court officials, the specific contents of the bestowed gifts, known as “ten segments,” were three pieces of silk (with one piece measuring four zhang), three lengths of cloth (with one length measuring five zhang), and four bundles of cotton (with one bundle weighing six liang). On the other hand, for “foreign guests receiving brocade and colorful silk,” the “ten segments” consisted of one piece of brocade, two pieces of damask, three pieces of gauze, and four bundles of cotton. It seems that the bestowed gifts prepared for foreign guests were more diverse and colorful.

While the Tang Dynasty engaged in border trade with residents beyond its borders, some items were prohibited from being traded. The Tang Dynasty’s “Regulations on Border Markets” stipulated that “brocade, damask, satin, gauze, embroidery, woven fabric, twill, silk, silk fabric, yak tail, pearls, gold, silver, and iron shall not be traded with various foreign regions or be taken into those regions.” Although both brocade and damask were included in the emperor’s bestowed gifts, they were not allowed to be traded, perhaps to showcase the uniqueness of imperial favor. Despite the essence of tribute trade being commerce, it inevitably bore profound political implications and was influenced by politics.

During the turmoil of the An Lushan Rebellion in the later period of the Tang Dynasty, the Uyghurs assisted the Tang Dynasty in suppressing the rebellion. As a reward, besides increasing bestowed gifts, the Tang Dynasty established a regulation to purchase Uyghur horses with silk. The annual limit was set at 100,000 pieces of silk, with 40 pieces of silk exchanged for one horse. This arrangement created long-term issues in the relationship between the two parties during the later period of the Tang Dynasty. The Uyghurs utilized the trade relationship to supply a large number of horses to the Tang Dynasty in exchange for silk and brought significant financial pressure to the empire.

Diplomatic activities carry the significance of energy exchange. The famous envoy Zhang Qian was sent to the Western Regions with the purpose of establishing an international united front to jointly resist the Xiongnu. Although he did not succeed in that objective, the opening of the Silk Road became a major transportation route between the cultural regions of the world at that time. Subsequently, Buddhism was introduced to China, and Chinese civilization spread to the West, all realized through this trade route. Cultural exchange is an important pathway for cultural development and often becomes part of diplomatic activities. The approximation of civilizations can promote mutual affinity, a phenomenon not exclusive to the present day. It was during Zhang Qian’s introduction that Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty learned about the distinction between “nomadic countries” and “walled states” in the Western Regions, realizing the cultural similarities between the latter and China. This sparked a strong interest in developing relations with the Western Regions. Ancient China, due to its firm pride in its own culture, actively embraced the inclusion of cultural factors in diplomatic activities.

art and architecture of the tang dynasty

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) was a peak period of economic and cultural development in feudal China, during which architectural technology and art also experienced significant advancements. The architectural style of the Tang Dynasty was characterized by grandeur, strictness, and openness. It had reached a mature stage of development, forming a complete architectural system. Tang architecture was grand in scale, magnificent in appearance, solemn and dignified, orderly yet not rigid, splendid without being delicate, and expansive without being ostentatious. It was both ancient and vibrant, a perfect reflection of the spirit of the time. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, spanning over a thousand years, including the famous “Foguang Temple,” there are still over a hundred surviving Tang Dynasty buildings in China, with the majority being brick and stone structures, while only four remaining wooden structures from the Tang Dynasty are all located in Shanxi Province.

The Tang Dynasty was a period of architectural maturity in ancient China. Building upon the achievements of the previous Han dynasties, it absorbed and assimilated foreign architectural influences, forming a complete architectural system. This system consisted of urban buildings, palace architecture, Buddhist architecture, and more.

City and Fortress:

Dual Capital System

Chang’an + Luoyang

Grand Scale

The city of Tang Chang’an was 2.54 times larger than Han Chang’an, 1.45 times larger than Beijing during the Ming and Qing dynasties, 7.29 times larger than Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire during the same period, 2.87 times larger than Baghdad, built in 800 AD, and 6.39 times larger than Rome. The central axis of Tang Chang’an, Zhuque Street, was 150 meters wide, which is still exceptionally wide even by today’s standards. In the context of that time or ancient history, it should be considered the widest road. (The only regret is that such a wide street was actually an unpaved dirt road. It was inconvenient for officials to travel to court when it rained, unlike the description in Wang Xiaobo’s “Running to the Night with Red Hufu.”)

Mature Neighborhoods

Tang Chang’an had 108 neighborhoods, which can be understood as 108 small cities. It is somewhat similar to modern communities with comprehensive facilities. Each neighborhood was enclosed by rammed earth walls (with a wall base thickness of about 2.5-3 meters, adjacent to various street ditches, and a wall height of about 2 meters). Ordinary residents could only enter or exit the neighborhood gates, while nobles and temples were allowed to open their gates to the main streets. Therefore, shops were located inside the neighborhoods. Each neighborhood had gates on all four sides, and the opening and closing of the gates were signaled by bells and drums at sunrise and sunset, giving rise to the saying “Morning bells and evening drums.” Once the gates were closed, people were not allowed to walk on the streets, except during the period around the 15th day of the first lunar month each year when the gates remained open. The city had nighttime curfews, and people were not allowed to wander around the main streets outside the neighborhoods at night. There were patrols by officials and soldiers. However, the facilities inside the neighborhoods were relatively well-equipped, especially in densely populated neighborhoods, where nightlife remained vibrant even after the gates were closed.

The overall layout of Tang Chang’an City maintained a symmetrical pattern with a central axis. The north-south Zhuque Street served as the central axis, with equally arranged markets and neighborhoods on the east and west sides. Streets and neighborhoods were neatly aligned side by side, forming a grid-like intersection of east-west and north-south streets. The outer city walls were divided into grid-like sections, with each grid representing a neighborhood. As described in Bai Juyi’s poem: “Countless families resemble a game of Go, twelve streets akin to vegetable plots.”

Rational Layout

In fact, starting from the Cao Wei’s Ye City, there was a conscious effort to locate the palace district to the north of the city, greatly reducing the impact of the imperial palace on the common people. The functional zoning of Tang Chang’an City was even more explicit. It concentrated government offices within the imperial palace, separating them from the residential areas, ensuring that citizens wouldn’t accidentally wander into the official domains.

Palace Architecture:

Grandiose Buildings

Archaeological findings indicate that the largest single structure built during the Tang Dynasty was the Mingtang Hall, constructed during the reign of Empress Wu Zetian. It was the largest Mingtang Hall ever recorded in history. The first floor was a square with a side length of 90 meters and a height of 86.4 meters, equivalent to over 20 stories of modern buildings. Remarkably, it was built in just 11 months, demonstrating the exquisite craftsmanship of the Tang Dynasty. Although this magnificent hall, the largest wooden structure in Chinese architectural history, was located in Luoyang, not Chang’an, it unfortunately perished in a fire during the Tang Dynasty.

The grandest imperial palace of the Tang Dynasty, the Daming Palace, situated in the northern part of Chang’an City, was once the largest complex of brick and wooden palaces in the world. Its area was equivalent to three Palace of Versailles, four Forbidden Cities, thirteen Louvre Museums, and fifteen Buckingham Palaces, illustrating the magnificence of the Tang Dynasty.

Front Court and Inner Court

The Daming Palace can be divided into the Front Court and Inner Court. The Front Court primarily served for imperial assemblies, while the Inner Court was used for residence and leisure activities. On the east and west sides outside the palace, garrisons were stationed, and within the northern gate, the command office of the garrison, known as the “North Office,” was established.

Central Axis Symmetry

The palace complex of the Daming Palace followed a central axis symmetrical layout. The Front Court consisted of the central axis line formed by the Danfeng Gate, Hanyuan Hall, Xuanzheng Hall, and Zichen Hall. The Inner Court, centered around the Taiye Pool, comprised dozens of halls and pavilions, including Linde Hall, Sanqing Hall, Dafu Hall, and Qingsi Hall. The entire Daming Palace covered a width of 1.5 kilometers from east to west and a length of 2.5 kilometers from north to south, with an area of approximately 3.2 square kilometers. It was the largest among the “Three Great Inner Palaces.”

Three Great Halls System

The three major halls of the Daming Palace were the Hanyuan Hall, Xuanzheng Hall, and Zichen Hall, with the Hanyuan Hall serving as the main hall. The Xuanzheng Hall had the Imperial Academy and the Secretariat on its left and right sides, as well as the Hongwen and Hongshi Halls. On the east and west sides of the central axis, there were longitudinal streets that pierced through the three parallel palace walls, creating side gates.

Temples:

The number and scale of Buddhist temples constructed during the Tang Dynasty were astonishing. In the city of Chang’an alone, there were over ninety Buddhist temples, with some temples occupying an entire city block. The development of temples had a significant impact on the imperial treasury. During the reign of Emperor Wuzong of Tang in the fifth year of Huichang (845 AD) and Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou in the second year of Xiande (955 AD), two “anti-Buddhist” campaigns were carried out, resulting in the destruction of thousands of temples. Emperor Wuzong alone demolished forty thousand Buddhist temples. Although these campaigns were short-lived, temples quickly recovered. However, the destruction of Buddhist temples and pagodas during the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties periods was catastrophic, resulting in the preservation of only three wooden Buddhist halls and several brick and stone pagodas from the Tang Dynasty. Based on this, we can abstract the characteristics of Tang Dynasty temples.

Magnificent Bracketing System: Large brackets were a fundamental feature of wooden architecture in the Tang Dynasty. The grandeur of the brackets created a sense of depth in the roof eaves.

Simple and Robust “Chiwen”: “Chiwen” refers to decorative elements at the ends of the roof ridge. In Tang Dynasty wooden architecture, the “chiwen” was typically in the shape of a bird’s beak or tail.

Tall Eaves: The eaves of Tang Dynasty wooden architecture were high and curved upwards, often divided into upper and lower layers.

Dark-Green Roof Tiles: The roof tiles of Tang Dynasty wooden architecture were typically of a dark-green color.

Thick Pillars: The pillars of Tang Dynasty wooden architecture were relatively thick, tapering from bottom to top, reflecting the aesthetic preference for a robust appearance.

Monochromatic Color Scheme: Tang Dynasty wooden architecture generally employed no more than two colors, often red and white or black and white.

Tombs:

Eighteen Imperial Tombs of Guanzhong

During the Tang Dynasty, including Emperor Wu Zetian, a total of 21 emperors were buried. Apart from Emperor Zhaozong (Li Ye) and Emperor Aidi (Li Zhu), the remaining 18 tombs of 19 emperors were arranged in a fan-shaped pattern, with the capital city of Chang’an as the center, extending from west to east. They stood majestically across the Guanzhong Plain, facing the Qin Mountains in the south.

Types of Imperial Tombs

The imperial tombs of the Tang Dynasty shared a common characteristic of facing north and south, with the terrain sloping from north to south. They can be categorized into two types:

a. “Mound-shaped Tombs”

These tombs were artificially constructed mounds with an inverted bowl shape, such as Xianling, Zhuangling, Duanling, and Jingling.

b. “Mountain-dependent Tombs”

These tombs utilized natural mountain slopes. Stone tunnels called “xiandao” were carved on the southern side of the mountains, and underground palaces were constructed at the base of the peaks. Examples include Zhaoling, Qianling, and Tailing, among the 14 tombs distributed along the Beishan Mountain Range.

Imperial Tomb Complexes

The imperial tombs of the Tang Dynasty were surrounded by tomb walls, forming vast tomb complexes together with the corresponding structures.

a. Layout

From Qianling onwards, the tomb complexes were divided into three sections, distinguished by three pairs of gate towers arranged from north to south.

The first section, located north of the first pair of gate towers, contained the burial mound and the Xian Dian (Hall of Worship), which constituted the main buildings of the tomb complex.

The second section, between the first and second pairs of gate towers, encompassed the Sacred Way of the tomb, adorned with various stone pillars, tablets, figures, and animals, symbolizing the imperial processions.

The third section, between the second and third pairs of gate towers, housed the tombs of meritorious officials and close relatives.

b. Main Structures

Xian Dian (Hall of Worship)

The Xian Dian is located within the inner city’s south gate, directly facing the burial mound. It serves as a place for conducting sacrificial ceremonies and paying respects to the relics of the deceased emperor.

Qingu (Imperial Underground Palace)

The Qingu, also known as the Lingxia Gong (Palace Beneath the Tomb), is situated southwest of the outer city within each tomb complex. It serves as the residence for the officials responsible for guarding the tomb and the daily attendants.

Tang Imperial Burial Accompanying Tombs

a. Burial Accompaniment and Secondary Burial System

Early Tang Dynasty

After the death of meritorious officials and close relatives, they were allowed to be buried alongside the imperial tombs and were granted burial plots and funeral accessories. Many of the founding heroes of the Tang Dynasty, such as Li Jing, Cheng Yaojin, and Yu Chigong, were honored with burial accompaniment at the Zhao Tomb (Zhaoling).

Mid-Late Tang Dynasty

a. In the mid-late Tang Dynasty, the number of accompanying tombs significantly decreased, and the practice was limited to members of the imperial family.

b. Representative Accompanying Tombs: Tomb of Crown Prince Yide and Tomb of Princess Yongtai

Above-Ground Structures

Both tombs were “mound-shaped tombs.” The layout of Princess Yongtai’s tomb complex is rectangular, with the burial mound in an inverted bowl shape. On the southern side of the burial mound, there are remnants of twin gate towers, along with stone lions, stone figures, and stone huabiao on both sides of the Sacred Way.

Underground Structures

Both tombs consist of long inclined passageways leading to double-chamber brick tombs. They include a tomb passage, six passage openings, seven courtyards, eight niches, front and rear walkways, and front and rear chambers. Each rear chamber contains a pavilion-style stone coffin. Extensive murals are painted in the underground chambers.

Grave Goods

The tomb of Crown Prince Yide yielded over 1,900 artifacts, including painted pottery figurines, as well as gold, jade, copper, and iron items. Eleven marble epitaph fragments filled with golden inscriptions were discovered, providing ample evidence of the hierarchical burial rituals akin to those of the imperial family.

c. Representative Accompanying Tomb: Tomb of Crown Prince Zhanghuai, Li Xian

Composition

The tomb consists of a double-chamber brick tomb with inclined passageways, passage openings, courtyards, niches, front and rear walkways, and front and rear chambers. The rear chamber contains a pavilion-style stone coffin.

Murals

The tomb passage, walkways, and chambers are adorned with colorful murals, including well-known depictions of horse polo, diplomatic envoys, and birds capturing cicadas.

Stele:

The appearance of steles originated in the Tang Dynasty and was closely associated with the “Fotuo Zunsheng Tuoluoni Jing” (Buddha’s Summit Supreme Talismanic Sutra). The Tang Dynasty left behind numerous carved talismanic steles, serving as ample evidence for the wide dissemination of talismanic beliefs during that era.

Steles differ from pagodas. Although both are rooted in the history of Buddhist architecture and share certain stylistic similarities, they belong to different categories.

Chinese steles are mostly made of stone, with fewer iron castings. They come in various shapes, including cylindrical, hexagonal, and octagonal. They consist of three parts: the base, body, and top. The body is inscribed with talismanic scriptures, while the base and top are adorned with floral patterns, cloud motifs, Buddha, and Bodhisattva figures. Steles can have two, three, four, or six tiers, and they can be square, hexagonal, or octagonal in shape. Among them, the octagonal form is the most common. The body of the stele stands atop a three-tiered pedestal, separated by lotus seats and a canopy. The lower section of the pillar is inscribed with scriptures, while the upper section bears inscriptions or dedicatory texts. The pedestal and canopy feature carvings of heavenly beings, lions, arhats, and other figures.

Tang Pagodas:

Tang pagodas can be classified into several types based on their architectural forms, including tower-style pagodas, multiple-eave pagodas, single-story pagodas, Lamaist pagodas, and others. The diamond throne pagoda is also considered a type, but it did not appear in the Tang Dynasty, so it will not be discussed here.

Tower-style Pagodas

Tower-style pagodas imitate traditional multi-story wooden structures and appeared early on. They were the most widely used type of pagoda throughout Chinese history. The periods of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, Tang Dynasty, and Song Dynasty marked the peak of tower-style pagodas, which were distributed throughout the country. The plan of these pagodas was square before the Tang Dynasty, and octagonal forms became more common from the Five Dynasties period onwards, with fewer hexagonal examples. Brick and stone were the main materials used in Tang pagoda construction.

Multiple-eave Pagodas

Multiple-eave pagodas have a taller base and are crowned with 5 to 15 (odd number) eaves, most of which are not intended for climbing or sightseeing. Their significance differs from that of tower-style pagodas. Although some multiple-eave pagodas can be ascended, the small windows and enclosed spaces limit the viewing experience compared to tower-style pagodas. Brick and stone are commonly used in their construction.

The plan of these pagodas varies. The Songyue Temple Pagoda is the only example with a twelve-sided plan, while Tang pagodas are mostly square, and Liao and Jin Dynasty pagodas tend to be octagonal.

Single-story Pagodas

Single-story pagodas are often used as funerary or Buddha image enshrinement pagodas. In the Tang Dynasty, the exterior of such pagodas began to incorporate elements of traditional Chinese architecture, closely imitating wooden structures and featuring various components such as columns, brackets, and dougong.

These pagodas have square, circular, hexagonal, or octagonal plans.

Lamaist Pagodas

Lamaist pagodas are mainly found in regions such as Tibet and Inner Mongolia, serving as the main pagodas of temples or tombs for monks.

Tang dynasty dance

The Tang Dynasty was considered a golden age in the development of ancient Chinese music and dance. The art of music and dance saw significant progress and flourished during this period. Two aspects can be highlighted: the prosperity of creative works in music and dance, and the prevalence of music and dance activities.

Prosperity of Creative Works in Music and Dance

Building upon the traditional music and dance arts of the Han and Wei dynasties and incorporating achievements from ethnic minority and exotic dance forms, the Tang Dynasty actively and passionately engaged in the creation of music and dance, leading to a notable increase in the variety and quantity of these art forms. This was evident in both courtly and folk music and dance.

Courtly Music and Dance

Courtly music and dance in the Tang Dynasty consisted primarily of yaying (elegant music) and yanyue (banquet music). The system and functions of yaying inherited traditional practices, with the addition of compositions like “Qin Wang Po Zhen Yue” (Music for the Qin King Breaking the Enemy’s Formation), “Gong Cheng Qing Shan Yue” (Music for Celebrating Achievements and Virtuous Deeds), and “Shang Yuan Yue” (Music for the Lantern Festival). Comparatively, the creative works in yanyue flourished during the Tang Dynasty. The court initially inherited the nine departments of music from the Sui Dynasty and later underwent reforms and innovations.

In the 11th year of Emperor Taizong’s Zhenguan era, the “Li Bi” (ceremony completion) was abolished and “Yan Yue” was added, taking the lead among the nine departments of music. Subsequently, due to the unification of the Gaochang Kingdom, in the eleventh month of the sixteenth year of the Zhenguan era, during a banquet for the officials, “Gaochang Ji” (Gaochang tunes) were included. It was only then that the ten departments of music were fully developed, encompassing many music and dance compositions.

During the years from Emperor Taizong to Emperor Xuanzong, the Tang artists established the system of “Li Bu Ji” (standing performance) and “Zuo Bu Ji” (seated performance) based on the foundation of the initial nine and ten departments of music. “Li Bu Ji” referred to standing performances in the hall, while “Zuo Bu Ji” referred to seated performances in the hall. It is evident that the yanyue of the Tang Dynasty underwent significant development compared to previous periods, not only in terms of variety but also in terms of quantity.

Folk Music and Dance

Folk music and dance in the Tang Dynasty often portrayed the lives of the working people, and as such, it was characterized by its authenticity, simplicity, liveliness, and sincere emotions. There was significant development in the creation of folk music and dance during the Tang Dynasty, particularly in the rise of folk songs and the prevalence of folk storytelling and Buddhist narrative poetry. Folk songs emerged as a new form of song in the Sui and Tang Dynasties.

At that time, there was a widespread popularity of “Hu Yi Li Xiang Zhi Qu,” which referred to traditional Han melodies and tunes imported from the Western Regions and other areas. In the era when yanyue was prevalent, musicians and literati used these tunes to compose lyrics and songs, accompanied by musical instruments, giving rise to folk songs. The creation of folk songs gradually increased during the Tang Dynasty, and the Tang and Five Dynasties period saw the collection of over a thousand Tang folk song lyrics in the “Complete Compilation of Dunhuang Songs,” including famous works like “Wang Jiangnan.” Prominent poets such as Bai Juyi and Li Huang also composed lyrics for folk songs.

Folk storytelling and Buddhist narrative poetry emerged and became popular during the Tang Dynasty with the increasing influence of Buddhism and the growth of the urban middle class. The primary forms of folk storytelling were the “sujiang” (secular lectures) and “bianwen” (narrative poems related to Buddhism). Sujiang involved preaching Buddhist scriptures through chanting and singing and had its origins in the ancient qingshang melodies.

Sujiang performances were often held in temples, with renowned monks like Wenxu and Kuangyin serving as speakers. The audience consisted mainly of monks and a large number of Buddhist followers. The form of sujiang included reciting Buddhist names, chanting Sanskrit sounds, and delivering sermons.

Bianwen refers to the written scripts for sujiang performances. Bianwen employed accessible language accompanied by captivating music to narrate stories from Buddhist scriptures and sometimes historical events. Representative examples of bianwen include “Mulan Bianwen,” “Vimalakirti Sutra Bianwen,” “Subduing Demons Bianwen,” and “Tomb of King Bianwen.” The creative expressions of folk music and dance not only enriched the artistic and spiritual lives of ordinary people but also enriched the artistic treasury of the Chinese nation.

tang dynasty painting style

Reasons for the Prosperity of Painting in the Tang Dynasty:

Social Development and Painting in the Tang Dynasty

The flourishing literature of the Tang Dynasty had a close relationship with the social development of the era. After the establishment of the Tang Dynasty, the rapid recovery and development of the economy created a highly favorable social environment for the cultural development of the Tang Dynasty.

The open-mindedness and inclusiveness of the Tang people facilitated the fusion and development of foreign cultures, creating a conducive environment for cultural prosperity. The development of painting in the Tang Dynasty built upon the foundation laid by the art of the Sui Dynasty. Various art forms in the Tang Dynasty, including painting, calligraphy, sculpture, dance, and music, influenced and mutually reinforced each other’s development.

Painting Art and Religion in the Tang Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty actively summarized the developmental experiences of previous cultural periods and pursued innovative developments based on this foundation, leading to an unprecedented flourishing of Tang culture. Buddhism, in particular, underwent sinicization during this period and gradually reached its peak. The first Chinese Buddhist sects formed during the Tang Dynasty, starting with the “Three Treatise School” established by Sui Jizang. Subsequently, influential sects such as Tiantai, Huayan, Chan (Zen), and Esoteric Buddhism emerged, linking human consciousness, nature, emotions, and cosmic views and proposing significant philosophical concepts that were inherited by Song Dynasty Neo-Confucian scholars.

In the later period of the Tang Dynasty, the Chan (Zen) sect, which emphasized sudden enlightenment and transcended reliance on written words, gained widespread popularity. Additionally, the Pure Land sect, which focused on the practice of chanting the Buddha’s name, exerted a significant influence on the lower social classes. With the high development and prosperity of Tang culture, the center of Buddhist dissemination shifted from India to China.

Taoism also experienced its heyday in the early Tang Dynasty, with the “Shangqing School” having the greatest influence. This Taoist school advocated gradual spiritual cultivation. In the later period of the Sui and Tang Dynasties, some foreign religions gradually entered China. Nestorian Christianity, originating from Syria, was one such example, and the “Monument of the Spread of the Religion of Light from Great Qin to China” unearthed in Xi’an provides evidence of the dissemination of Nestorianism during that time. The Buddhist art that emerged within the context of religious prosperity had a profound influence on Tang Dynasty painting, encompassing color schemes, lines, motifs, and artistic styles.

The Ritual and Educational Function of Tang Dynasty Painting

The rulers of the Tang Dynasty directly organized painting activities, such as creating portraits of meritorious officials, emperors, and kings, as political propaganda tools to “guide and assist people in observing social norms.”

In the early Tang Dynasty, figure painting pursued a style of “capturing the spirit through forms,” but its actual purpose was to fulfill its educational function. With the development of Tang society, economy, and the resulting national confidence due to intellectual openness, Tang figure painting exhibited artistic characteristics that emphasized subjectivity, social aspects, and the integration of aesthetics.

In terms of technique, Tang Dynasty painting expressed “intention” by capturing the aesthetic mood that harmonized with the Dao, combining stillness and movement to depict two levels of spiritual subjectivity. Through the application of such painting techniques, flourishing Tang figure painting achieved a state where form conveyed spirit, reaching a realm of combined imagery.

One of the representative works is Wu Daozi’s predominantly ink-wash painting, “Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk.” This painting depicts a scene from the 15th year of the Zhenguan era, featuring an encounter between Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty and Princess Wencheng, who was sent as a bride to the Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo. The painting highlights the expressions and details of the figures, conveying a sense of intimate emotional exchange between them.

The prevalence of Buddhism promoted the development of folk art education, particularly through collaborative mural painting as the primary method of transmission between masters and disciples. The art education system proposed the artistic principle of “learning from nature,” providing a favorable opportunity to focus on personal sensory experiences.

The Development of Tang Dynasty Painting Art

The development of painting in the Tang Dynasty went through three stages, driven by the flourishing feudal economy and the demands and preferences of the ruling class. The first stage was the early Tang period, during which painting art inherited and developed traditional techniques from the Central Plains while continuously incorporating influences from surrounding ethnic groups and foreign painting art. Tang painting art flourished and innovated during this stage.

The second stage was the heyday of the Tang Dynasty, characterized by significant advancements in figure painting. The development of religious painting was closely related to the development of figure painting. Wu Daozi and Yang Huizhi were major representatives in this field.

Wu Daozi’s religious murals, numbering over 300, formed a unique style known as “Wu’s mastery in the wind.” The Dunhuang murals, preserved in Dunhuang, stretch for a total of 25 kilometers. Their “illustrated sutras” (paintings that visually interpret the ideas of a Buddhist scripture) exhibit intricate compositions, magnificent lines, and highly valuable depictions of figures and animals.

Secular painting focused on reflecting aristocratic life, with Zhang Xuan being one of the representative painters. The painting style during this period deviated from the delicate and vivid style of the early Tang period and developed towards a bold and grand style, leaving a profound and extensive influence on the history of Chinese painting.

The third stage occurred after the An Lushan Rebellion. During this period, paintings of noblewomen became prevalent, characterized by profound, melancholic, and elegantly expressive aesthetics. Other common painting themes included aristocratic banquets, recreational activities, and the lives of literati and scholars. Painters such as Sun Wei and Zhou Fang excelled in portraying noblewomen with remarkable accuracy.

tang dynasty calligraphy

The Tang Dynasty was indeed the pinnacle of cultural and artistic development, and its achievements in calligraphy directly reflected the prosperity of the dynasty.

I. The Gradual Evolution of Calligraphy

In the early period of the Tang Dynasty, society gradually stabilized after the constant turmoil at the end of the Sui Dynasty. With the economy recovering and society experiencing stable development, literature and art began to flourish.

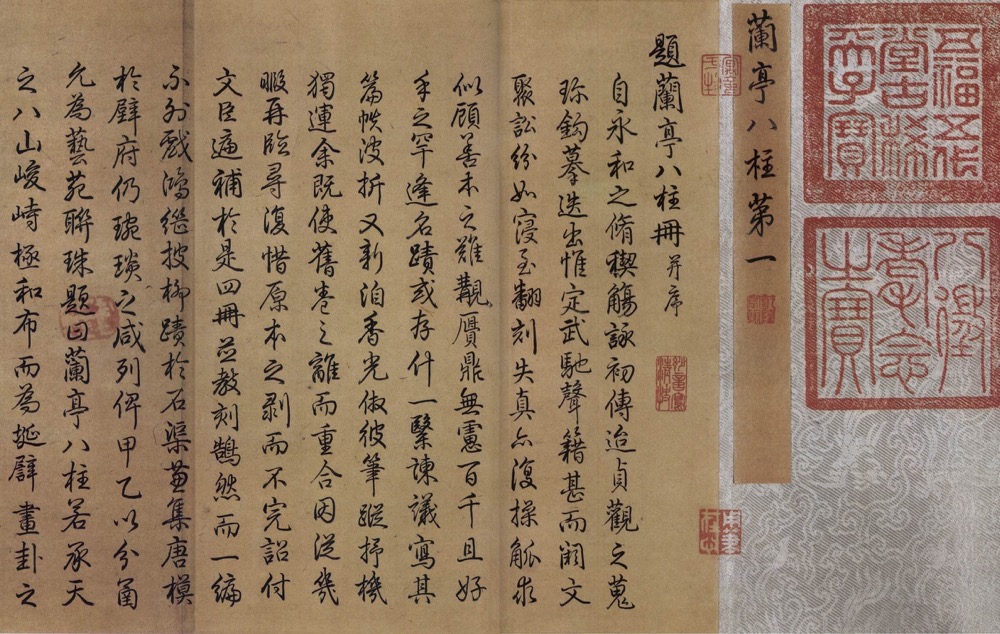

Emperor Taizong of Tang, Li Shimin, had a great passion for calligraphy. He advocated for the people across the country to study calligraphy and actively promoted the calligraphy of Wang Xizhi, which played a significant role in the development of calligraphy. During this period, the most representative figure in calligraphy was Ouyang Xun.

With the progress of society, the “Prosperous Era of Kaiyuan” and the “Good Governance of Zhenguan” emerged, bringing about significant changes in the style of calligraphy. The calligraphic style during this period gradually evolved from the vigorous and upright style of the early Tang Dynasty towards a more robust direction. The cursive script, in particular, broke free from the influence and constraints of Wang Xizhi, developing its own unique style that belonged to the era.

During this period, calligraphy masters such as Zhang Xu, Yan Zhenqing, and Liu Gongquan emerged. They achieved new heights in regular script and cursive script, although not surpassing the ancients, their achievements were still highly remarkable.

In the late Tang period, calligraphy flourished with even more diverse artistic expressions. Despite the gradual decline of the country, new ideas emerged in both regular and running scripts, and representative figures like Du Mu appeared.

II. Development of Calligraphic Theory

During the Tang Dynasty, the theoretical and systematic aspects of calligraphy gradually improved. Many renowned calligraphers of the time shared their insights, and even Emperor Taizong, Li Shimin, wrote four books to discuss the theoretical knowledge of calligraphy. He believed that writing should be accompanied by a deep understanding, where thoughts and actions should align harmoniously for success.

Ouyang Xun emphasized the proper handling of the brush and focused on concentrated contemplation. Sun Guoting approached calligraphy from a historical perspective, emphasizing emotions and resonance generated during the act of writing, earning him greater recognition from later generations. Zhang Huai’guan provided detailed explanations of calligraphy from different periods, offering meticulous introductions and evaluations of each script style’s origin and development.

III. The Artistic Spirit of Calligraphy

The calligraphy art of the Tang Dynasty emphasized adherence to artistic principles, encompassing a diverse range of approaches. The principles of art not only referred to technical requirements in writing but also placed importance on the artist’s character and moral cultivation. Yan Zhenqing, a calligrapher of the Tang Dynasty, was a model figure who emphasized adherence to principles.

Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy possessed not only high aesthetic value but also expressed elevated moral standards. His calligraphy exemplified the Confucian spirit of loyalty and filial piety, giving it a vibrant and upward vitality.

Since the Wei and Jin dynasties, calligraphy gradually developed and embarked on a path of continuous self-renewal, witnessing an awakening of consciousness. During the Tang Dynasty, cultural fusion and development were underway, allowing calligraphy to absorb the essence of predecessors while incorporating elements of contemporary literature and art, resulting in calligraphy styles with distinct contemporary characteristics.

Simultaneously, as an inclusive era with fewer demands on the people, calligraphers began to pursue their individuality and liberate their nature. Romanticism emerged, and calligraphic styles began to align with the content being written.

During this period, the spirits of abstraction and realism coexisted. As calligraphy inherently represents various forms of Chinese characters, with the overall basis being the stroke of the characters, calligraphy falls between the concrete and the abstract. It cannot be overly specific or excessively abstract, which enhances the artistic quality of cursive script.

Tang poetry

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) was the pinnacle of classical poetry development in China. Tang poetry is one of our country’s outstanding literary legacies and a brilliant gem in the world’s literary treasury. Despite being over a thousand years old, many poems are still widely circulated.

Tang poetry encompasses a wide variety of forms.

In terms of ancient-style poetry, there are mainly two forms: five-character (pentasyllabic) and seven-character (heptasyllabic) poems. There are also two forms of regulated verse: quatrains (jueju) and regulated verse (lvshi).

Quatrains and regulated verse are further divided into five and seven-character variations. Therefore, the basic forms of Tang poetry can be classified into six types: five-character ancient-style, seven-character ancient-style, five-character quatrains, seven-character quatrains, five-character regulated verse, and seven-character regulated verse.

Ancient-style poetry has more flexible requirements for rhyme and rhythm. The number of lines and the length of the poem can vary, and rhyme schemes can be changed. Regulated verse, on the other hand, has stricter requirements for rhyme and rhythm. The number of lines is fixed, with four lines for quatrains and eight lines for regulated verse. The syllable patterns in each line follow certain rules, and rhyme schemes cannot be altered. Regulated verse also requires the four middle lines to be parallel in structure.

Ancient-style poetry inherits the style of previous generations, hence its name “gu-feng” (ancient style). Regulated verse adheres to strict prosody rules, so some refer to it as “ge-lv-shi” (regulated verse).

tang dynasty eunuchs

In the early Tang Dynasty, the central government was strong, and the monarchs had absolute power, so eunuchs had little influence during this period. However, the emergence of eunuch power was laid during the An Lushan Rebellion, when most civil officials were weak and military commanders had achieved significant military accomplishments.

During the reigns of Emperor Suzong and Emperor Daizong, eunuch power was still in the developmental stage and did not pose significant harm. However, during the reign of Emperor Dezong, signs of irreversible eunuch dominance began to appear. This was because during this period, eunuchs gained control over the imperial guards of the Tang Dynasty, specifically the Shence Army. Under Emperor Xianzong, all the imperial guards except the Shence Army were abolished, and thus the eunuchs completely controlled the military force of the Tang Dynasty. Furthermore, during Emperor Xianzong’s reign, eunuchs were appointed as the heads of the Imperial Secretariat (Shumi Shishi), and this became a convention in the Tang Dynasty.

In summary, the issue of eunuch dominance plagued the emperors of the Tang Dynasty in the middle and late periods. The emperors were powerless to completely eradicate this nightmare. Even during the reign of Emperor Zhaozong in the late Tang Dynasty, eunuchs still held control over the court. It was not until Zhu Wen entered Chang’an and massacred the eunuchs that this political force finally exited the stage of history. When we carefully examine the history of the middle and late periods of the Tang Dynasty, we can see that the problem of eunuch dominance had a subtle but significant impact on the Tang Dynasty. So, what kind of harm did eunuch dominance in the middle and late Tang Dynasty bring to the empire?

Firstly, the most severe harm caused by eunuch dominance in the middle and late Tang Dynasty was the weakening of imperial power. In fact, since the reign of Emperor Suzong, successive Tang emperors were threatened by eunuch power. For instance, shortly after Emperor Daizong ascended the throne, he immediately honored the eunuch Li Fugu as “Shangfu” (Senior Father), which was the first such case in ancient history. Conversely, Emperor Xianzong, Li Chun, was assassinated by eunuchs. According to the historical record in the “Old Book of Tang,” it states, “He died in a violent manner, and all claimed that he was assassinated by the eunuch Chen Hongzhi, but the official history avoids mentioning it.” This demonstrates that eunuch power posed a significant threat to the emperor in the middle and late Tang Dynasty.

According to the “New Book of Tang,” it is recorded that “since Emperor Muzong, seven emperors out of eight in the Tang Dynasty were placed on the throne by eunuchs.” In other words, after Emperor Muzong, the Tang emperors were essentially installed by eunuchs. For example, Emperor Wuzong had five sons during his lifetime, but it was Emperor Xianzong’s thirteenth son, Crown Prince Guang, who succeeded him. This is intricately linked to the rise and fall of eunuch power. In terms of historical development, the eunuchs’ enthronement of emperors actually represented a loss of imperial power. The emperors could no longer decide their own successors, which further weakened their authority