The Chinese Opera is considered an ancient art form with a charm that’s endured all these years. Even today, foreigners visiting China, don’t fail to attend a performance, especially opera lovers.

what is Chinese opera?

Known as Xiqu in Chinese, this form of art is considered one of the world’s three oldest dramatic art forms. The roots of this form of musical theatre can be traced back to the earlier periods of Chinese history. An opera school by the poetic name Liyuan which translates to Pear Garden was opened during the Tang dynasty by emperor Taizong. Performers who attended the school were referred to as the disciples of the Pear Garden. By the Yuan dynasty, Xiqu had become a traditional art form for court officials and emperors and in the Qing dynasty, it became fashionable even to the ordinary people.

Even today, Chinese opera is considered a national essence and an important part of Chinese culture and tradition. To help you better understand Chinese opera, this post will cover, what its purpose is and what is involved in the performance. We will also share with you the different types and how Chinese opera and how it differentiates from western opera.

What Is the Purpose of Chinese Opera?

What started as a simple song and dance performance has slowly evolved. For the most part, Chinese Opera was performed for entertainment purposes. It however also carried Chinese culture and traditions since the performances were derived from Chinese legends and folklore.

The earliest form of Xiqu was Canjun opera. It was a simple comic drama involving only two performers, the corrupt officer Canjun and the jester who ridiculed him called Green Hawk. During the six dynasties, more various songs and dances came up. In the Northern Qi dynasty for example the song and dance dram included masked dance and was called the King of Lanling, performed in honor of Gao Changgong who went to battle wearing a mask. Other song and dance dramas at the time included Botou, the story of a grieving son who sought to avenge his father’s death by seeking the tiger that killed him. The dancing singing woman was a story of a woman beaten by her alcoholic husband.

By the Tang dynasty, these dramas became more complex with more dramatic twists and now involving at least four performers. This was around the time the earliest known Chinese opera troupe. Given that the opera was in classical Chinese, it was initially only performed for the emperor’s entertainment and the royal court. During the Yuan dynasty, performers singing or speaking in the Chinese vernacular tongues became more popular. As such even the commoners began to understand and enjoy Xiqu.

Throughout the years from the Yuan dynasty until the Qing dynasty and even after the establishment of the Republic of China, Xiqu continued to evolve. It had now become an amalgamation of many art forms including, dance, music, acting, make-up design, and costumes. This marked the beginning of the Cultural revolution from 1965 to 1976. During this period, opera was banned and troupes were disbanded with performers being persecuted. Only the eight model operas were allowed to be performed. The rest were seen as poisonous weeds that prevented the Chinese from progressing. It wasn’t until 1976, after the fall of the Gang four when opera began to be revived again.

Even today in the 21st century, Chinese opera is rarely performed publicly, only in, formal opera houses. Although, Xiqu may be presented during the Chinese Ghost festival on the lunar seventh month to entertain the spirits and the audience. Still, Chinese opera is considered an important part of Chinese history and traditions.

What Is Involved with Chinese Opera?

As mentioned before, Chinese opera is a type of musical theater that’s an amalgamation of various art forms that evolved over many centuries. It came from dances and folk songs to combining art, music, and literature into one performance on stage.

Today, Chinese opera involves various exaggerated facial make-up styles and elaborate costumes. These were used to symbolize a character’s personality, role, and fate in the performance. A red face, for example, represented loyalty and bravery, a white and yellow face meant duplicity. A black face, on the other hand, symbolized valor, while golden and silver faces represented mystery.

Xiqu is also accompanied by traditional instruments like the gong, lute, and erhu. It also involves unique melodies and beautifully written dialogue. Another fascinating accompaniment in the performances is the acrobatics. When a performer acts as a spirit, they may sometimes spray fire out of their mouths or squat and gallop while acting like a dwarf. This increased the authenticity of the performances.

Difference Between Chinese Opera and Western Opera

When comparing the Chinese opera to the Western, you’ll realize that the Chinese opera is uniquely different from it. Although both are an interpretation of life and representation of their respective cultures and stories, the number of differences set them apart. To begin with, Xiqu is at least 1,900 years older than any Western opera including Mozart and Wagner. The following are some of the main differences:

Performing Style

When it comes to performance, the Chinese opera has a rigid style of a symbolic visual show. For instance, to imitate riding a horse, the performer will tie a horsewhip on its wrist and wave it around as if riding a horse. For Chinese opera, the performance is more than stylized singing, even the actions are important in telling the story. In contrast, Western opera focuses more on emotional expression and powerful singing. Their performance style is more fluid and life-like as well as self-explanatory.

Role Classification

When it comes to determining the roles played, Chinese opera has four fixed roles that performers are grouped under. These roles are heroine, hero, comic, and Jing (painted face). The performers then train their voices to fit these particular roles. In Western opera, however, there are a variety of roles that are determined by the voice pitch. That means that the customary role is determined by the performer’s vocal range.

Another thing is that in Chinese opera, a heroine can be played by a man and a hero by a woman. In Western opera that rarely ever happens.

Stage Set-Up

For Chinese opera, the stage required can be a simple platform or even a make-shift stage. Usually, for Xiqu performances only one side of the stage is shown to the audience, unlike the Western opera stage. Theirs include various props that are vivid. Hence a Western opera performance requires a complicated stage set-up.

Vocal Acrobatics and Musical Instruments

In Western opera, the vocal of the performer includes sung melodies that are clear and strong. This is usually accompanied by a full orchestra. With Chinese opera, a unique singing technique is required for each role, and may sometimes involve droning and crooning of a syllable with a startling pitch variation. This is accompanied by traditional Chinese instruments like gongs and drums.

Make-up

Like the performance style, the make-up styles used in Western opera are simple and life-like. Chinese opera make-up styles are a bit more complicated. It’s usually thick, unnatural, and heavily dependent on color. That’s because the color is used to symbolize the role of the character.

Different Types of Chinese Opera

Over the years of evolution, Chinese opera today exists in various forms based on regional local traits and accents. There are over 300 regional Chinese opera styles but, in this post, we’ll focus on the four main ones which are as follows:

Beijing Opera

Also called Peking opera, it is considered the perfect example of Xiqu, which originated from Beijing but has since spread across the country as a symbol of Chinese culture. It is characterized by vivid make-up, complicated plots, and a beautiful stage set-up and costume.

The plots are usually about political affairs more than romance. They include stories of historic and even supernatural beings who existed centuries ago. Compared to other Chinese operas, Peking has a stricter requirement when it comes to songs, costumes, makeup, and performance.

Cantonese Opera

This type of opera is based in South China and some Chinese communities overseas that was first performed during the Ming dynasty. You’ll mostly find it performed in Hong Kong, Guangdong, Malaysia, and other Chinese-influenced countries in the West. While this style incorporates older Chinese opera forms and instruments it also incorporates western instruments like the violin and saxophone as well as some western play tunes.

Cantonese opera is also characterized by its elaborate make-up styles that use different color shades and shapes to represent the state and traits of the character. This style is also subdivided into two kinds. Mo (martial arts) performances are fast-paced and about bravery war and betrayal. Mun’s (intellectual) performances are slower and more passive. They use vocals, flowing water sleeves, and facial expressions to express complex emotions. Most of the stories are about romance, ghosts, and classic Chinese myths and tales.

Shanghai Opera

This style is also known as Huju opera and it came about around the same time as Peking opera. Unlike Beijing opera, this version uses Wu Chinese dialect and the folk songs are based on Huangpu River regions.

Huju opera is characterized by simple make-up and costumes that are almost like ordinary people’s streetwear from the pre-communist era. Many of its performances seem to have some western influence.

Shanxi Opera

Also known as Qingqiang opera that first appeared in the Qin dynasty and became popular in the Tang era. The singing, acting styles, melodies, and plot lines mostly come from the Shanxi province. During the Qing dynasty, when Qingqiang was introduced to the Beijing court, it became incorporated into the Peking opera because the imperial court enjoyed it so much.

Like Huju opera, this style is also divided into two. There is the joyful tune, Huan Yin, and the sorrowful tune, Ku yin. Most of the story plots are about fighting ad lack of loyalty. Some performances included special acrobatic effects like twirling and breathing fire.

what is Chinese opera called?

Chinese opera is called “戏曲” (xìqǔ) in Mandarin, which translates to “drama” or “theatrical performance.” It is a traditional form of performing arts in China, and it has a rich history that dates back centuries. There are several regional styles of Chinese opera, each with its own unique characteristics, music, and performance techniques. Some of the most well-known styles of Chinese opera include Beijing (Peking) Opera, Cantonese Opera (Yue Opera), Sichuan Opera (Chuanju), and Kunqu Opera. Each style has its own distinct costumes, makeup, singing, and acting styles, making Chinese opera a diverse and culturally significant art form in China.

what instruments are used in Chinese opera?

Chinese opera bands are an integral part of the comprehensive art form while maintaining relative independence in their performances. They are generally characterized by being small, diverse, and highly flexible.

The drum board serves as the conductor of the opera band (both in literary and martial arts plays) and acts as a bridge between singing and accompaniment. Additionally, it possesses the characteristic of independent solo performance. The drummer often conveys emotions and meanings through symbolic performances on the drum board. They not only ensure seamless ensemble playing by the entire band, perfectly coordinating with the performance, but also strive to highlight different characteristics in each play.

Although the combination of instruments varies across different opera genres, the role of the principal instrument remains the same. The principal instrumentalist must be well-prepared for the emotional fluctuations, climactic moments, and handling of each singing segment. They must also have a deep understanding of the artistic personality of the performers, their strengths, and weaknesses to achieve seamless collaboration and synergy, creating a unique artistic style through long-term cooperation. The arrangement of other instruments is to support the principal instrument, enriching the overall timbre and combining with the unique characteristics of the principal instrument, contributing to the distinctive style of each opera genre. Each opera genre has its own unique basic instrument combination. For example, Beijing Opera mainly features Jinghu as the principal instrument, accompanied by Yueqin and Xiaosanxian, which greatly influences the distinct sharpness and delicate tonal style of Pihu. Hebei Bangzi uses Xiaobangdi to match with Banhu, creating a high-pitched tone. Jinju uses Erguzi, Siguxian, and Xiaosanxian accompanied by Banhu, creating a particularly soothing atmosphere. Yugu uses Sheng, Di, Erhu, and Sanxian accompanied by Banhu, resulting in a more full and intense style. Kunqu uses Sheng and Sanxian with Qudi, appearing soft and delicate. Due to the different combinations of instruments and their unique timbres and techniques, a diversity of musical styles in Chinese opera is formed (see principal instruments).

Colorful instruments are generally versatile, such as Suona, Dongxiao, and Zheng, used to create special atmospheres and moods. For lively and joyous scenes, large and small Suona are often used, accompanied by gongs and drums. For tranquil and elegant scenes, Dongxiao and Zheng are commonly used. For battle scenes, war drums are added to enhance the momentum.

Chinese opera has a unique way of using percussion instruments, and although the basic components of each opera genre’s percussion instruments are similar, the form, timbre, drumming patterns, and playing methods vary. For example, in Beijing Opera, Hebei Bangzi, and Yugu, the large gongs have slightly raised centers and are struck with cloth-wrapped hammers. In Guangdong Han Opera, the large Su gong has different pitches between the center and the rim and is struck with cloth-wrapped wooden mallets, producing different sounds when struck and stroked. Additionally, each opera genre uses different drum boards and clappers. For instance, Guangdong Opera uses Buyu Ban, Ce Ban, and Sha Ban; Hebei Bangzi uses Yugu, Jian Ban, and Banhu; Peking Opera uses Zaomu Bangzi; and Shanxi Wangqiang uses Copper Wangqiang, all of which are highly distinctive.

Chinese opera is an important component of traditional Chinese culture, and opera instruments are an indispensable part of opera performances. There is a wide variety of opera instruments, each with its unique timbre and expressive power. Let’s take a look at some of the opera instruments:

Beijing Opera Percussion: Beijing Opera percussion instruments are the main accompaniment in Beijing Opera performances, including big gongs, small gongs, big drums, small drums, and clappers. The resounding and powerful sounds of the gongs and drums create a majestic atmosphere, making them an essential part of Beijing Opera performances.

Erhu: The erhu is one of the traditional Chinese bowed string instruments and is commonly used in opera performances. The melodious sound of the erhu can express the emotions and atmosphere of the opera, making it an important accompanying instrument in opera performances.

Bangdi: The bangdi is one of the traditional Chinese wind instruments and is frequently used in opera performances. Its sharp sound can convey tension and a sense of suspense in opera performances, making it an important accompanying instrument.

Jinghu: The jinghu is one of the traditional Chinese bowed string instruments and is commonly used in Beijing Opera performances. The high-pitched sound of the jinghu can express heroism and passion in opera, making it an important accompanying instrument in Beijing Opera performances.

Yangqin: The yangqin is one of the traditional Chinese plucked string instruments and is often used in opera performances. The clear and melodious sound of the yangqin can express elegance and grace in opera, making it an important accompanying instrument in opera performances.

Cello: The cello is a Western classical instrument but is also used in Chinese opera. The deep and mellow sound of the cello can convey a sense of solemnity and stability in opera performances, making it an important accompanying instrument.

Matouqin: The matouqin is a traditional Mongolian bowed string instrument and is commonly used in Chinese opera. The unique sound of the matouqin can express the grassland style and boldness in opera performances, making it an important accompanying instrument.

Various theatrical performances use different musical instruments as accompaniments. Here are some examples:

Beijing Opera:

Jinghu: A high-pitched two-stringed fiddle used for Beijing Opera accompaniment. It has a small bamboo body and neck, with a bright and penetrating sound that provides strong support and complement to the singing.

Erhu: A traditional two-stringed bowed instrument commonly used in opera performances. Its melodious sound expresses emotions and atmosphere in the opera.

Yueqin: A plucked string instrument similar to the moon-shaped lute, often used in accompaniment.

Xiaokuai Ban: A small clapper used for rhythm and percussion.

Big Gong and Small Gong: Large and small gongs used for dramatic effects and rhythm in Beijing Opera.

Yu Opera (Yuju):

Banhu (Board Fiddle): A bowed string instrument and a major accompaniment instrument in Yu Opera.

Erhu: As mentioned before, also used in Yu Opera.

Pipa: A plucked string instrument with a pear-shaped body and frets, often used in Yu Opera accompaniment.

Yue Opera (Yueju or Shaoxing Opera):

“Xiangbi Sihuan” (Elephant Trunk Four-String) and “Duan Gan Zhuihu” (Short Neck Hanging Fiddle, actually “Quhu”): Lead instruments in Yue Opera accompanied by others like Erhu, Gaohu, Pipa, Yueqin, Sanxian, Zheng, Sheng, Suona, and Dizi.

Jingyun Drum (Jingyun Daggu):

Major accompanying instruments include Daxian (Large Three-String), Sihu (Four-String Fiddle), and sometimes supplemented by Pipa. Actors control the rhythm by hitting the drumboard themselves.

what is Chinese opera music?

The music in theatrical performances plays an irreplaceable role in shaping characters, expressing thoughts and emotions, and revealing the spirit or style of the drama’s theme. Chinese theatrical performances, from the Song and Yuan dynasties to the present, are all rooted in Chinese culture. They may share similarities and differences, but they all originate from the essence of Chinese culture. The variations mainly lie in the regional dialects and the musical styles, particularly the accompanying musical instruments.

For example, Yuan Zaju, which originated in the northern regions, uses the northern dialects. Yueju opera, on the other hand, is performed in the Wu and Yue dialects. Beijing Opera is performed using the Jing-Hu dialect, while Cantonese opera is performed in Cantonese. Each opera is accompanied by a distinct set of musical instruments, creating different styles. Kunqu opera uses instruments like flute, xiao (a type of vertical bamboo flute), sheng (a reed instrument), and pipa (a plucked string instrument) along with percussion instruments like drum, board, and gong. Beijing Opera, on the other hand, features stringed instruments like Jing-Hu, Erhu, Yueqin, and Sanxian, accompanied by Suona and flute, along with percussion instruments like drum, gong, cymbals, and qian (large metal clappers).

The differences in regional dialects and the resulting variations in sound quality due to different musical instruments create the distinct styles of various Chinese operas. Since the Song and Yuan dynasties, Chinese theatrical performances have been divided into northern and southern styles. The northern style includes the Yuan Zaju or Jin Yuan Zaju, prevalent in the northern regions. The southern style, known as the Yongjia Zaju, emerged in the southern region of Zhejiang and laid the foundation for the Ming and Qing legends. Wang Guowei pointed out the differences between these two styles: “The northern and southern operas of the Yuan Dynasty have slight similarities. Only the northern operas are sorrowful, majestic, and profound, while the southern operas are gentle, melodious, and winding, with little else to differentiate them.”

The styles and musical images of these different operas help to convey their respective literary spirits. Their distinct emotional colors, be it sorrowful, majestic, or gentle and elegant, infect the contemporary audience and future admirers.

In the context of theatrical performances, the music should also be attuned to the emotions and melodies of the characters. For example, Beijing Opera’s Xipi Qiang features various tunes such as Daoban, Yuanban, Manban, Kuaiban, Sanban, Yaoban, Erliu, Liushui, and Huilong, with each tune tailored to suit the plot. Even in portraying sorrowful moments, the rolling tones and crying style must be chosen based on the character’s emotional changes. The dramatic music propels the plot, while the emotional music emphasizes the characters’ feelings. Both serve the purpose of revealing the theme and spirit of the theatrical performance. In terms of sound quality, traditional Chinese musical instruments, such as strings that sound like silk, bamboo, or even flesh, are inferior to the divine sound of the characters they seek to portray.

Chinese theatrical music is a genre of traditional folk music and an essential artistic means for portraying characters’ thoughts, emotions, and personalities, as well as setting the stage atmosphere in theatrical performances. It is also a crucial distinguishing feature among different theatrical genres. The roots of Chinese theatrical music can be traced back to various music elements, such as folk songs, traditional music, dance, and instrumental music, making it an integral part of Chinese folk culture. This theatrical music possesses its distinct structural forms, expressive techniques, and artistic skills, exhibiting a strong national artistic style. From a historical perspective, theatrical music belongs to the musical drama of the Chinese people, and it significantly differs from Western opera and the tradition of individual professional composers.

Chinese theatrical music is essentially folk music. Its creation retains the nature of folk music to a large extent.

Firstly, theatrical music originates from the folk traditions and has a profound mass foundation. It maintains close connections with regional dialects, local folk songs, and various narrative music styles.

Secondly, the music of each theatrical genre is not the creation of a single composer but rather a collective product of long-term development within the folk tradition, representing the artistic wisdom of generations of people.

Thirdly, historical theatrical music continuously evolves through oral transmission. Due to varying conditions and dialects, the vocal styles can undergo changes. This variability allows the same vocal style to develop into different regional or stylistic variants within a single theatrical genre.

Traditional theatrical music continuously evolves through this process rooted in folk traditions.

Moreover, historically, theatrical music creators and performers were one and the same; their singing or playing was the process of composition itself. In other words, the process of composition was integrated with the process of performance. Therefore, the techniques and skills used in theatrical singing or playing often encompass the principles of composition.

The folk characteristics mentioned above are present in almost all vocal styles and theatrical genres, including those of ethnic minority theatrical forms. Kunqu is the only exception, as it underwent a transformation from folk origins through the reforms led by Wei Liangfu (birth and death dates unknown) and was standardized with refined literary tunes. However, Kunqu is also distinct from Western opera and its composers’ approach. Despite the intervention of literary tunes, Kunqu still maintains a certain degree of flexibility and regional variations in its performance.

Another characteristic of theatrical music is its programmatic nature. The programmatic structure is present in various aspects of theatrical music, from the overall music structure that runs through the entire drama performance to the specific structure, techniques, and applications of vocal styles, musical patterns, and percussion beats. The combination and application of these elements are indispensable in every aspect of theatrical performance. This creative approach does not reject tradition but rather achieves new synthesis and creativity based on traditional forms and means of expression. The application of programmatic techniques follows certain rules.

Different vocal styles and theatrical genres often have their distinct music programs. However, based on the logic of music, the requirements for programmatic structure are strict but can be flexibly applied in practice. This characteristic has proven to be an important means of creating stage imagery in theatrical performances. Chinese theatrical music’s professionalism, ethnic characteristics, and aesthetic significance derive from its folk nature and programmatic approach. These features continue to be preserved in contemporary theatrical music creation. The musical elements of theatrical performances consist of vocal and instrumental parts, with the vocal part being the central focus.

Within the structure of theatrical music, vocal parts play the most significant role. According to traditional Chinese aesthetics, singing by human voices is more touching and emotionally evocative than instrumental accompaniment. This is because while musical instruments can convey emotions, they cannot express meanings through words.

The portrayal of character images in theatrical music relies primarily on vocal performance, with beautiful singing and moving performances. Whether it is singing melodies or narrative styles, theatrical music can be categorized into three types: lyrical singing, narrative singing, and dramatic singing. Lyrical singing uses fewer words and more melodies, emphasizing the expression of inner emotions. Narrative singing contains more words and less melody, suitable for narrations and dialogue. Dramatic singing often involves freely paced and flexible rhythms, making it ideal for expressing intense and passionate emotions.

The alternation of these three musical styles creates the ever-changing dramatic nature of theatrical music. Many traditional theatrical plays endure on the stage due to the widespread popularity of their singing styles.

Chinese opera characters

Sheng: Sheng is one of the main roles in Chinese theatrical performances. It refers to male characters other than Jing (painted face) and Chou (clown). The term “Sheng” was first used in the Southern operas during the Song and Yuan dynasties, indicating the male lead role, equivalent to the Zhengmo in Yuan Zaju. In the Qing Dynasty, it evolved into four subcategories: Laosheng (old man), Xiaosheng (young man), Wai (military), and Mo (supporting roles). Based on their character attributes, personality traits, and performance characteristics, Sheng roles can be broadly divided into Laosheng, Xiaosheng, Wai, Mo, Wusheng (martial arts), and Wawasheng (child roles).

Dan: In Peking Opera, Dan refers to female characters. Within the Dan category, there are Qingyi (virtuous lady), Huashan (flower lady), Huadan (young female), Daoma Dan (female warrior), Wudan (martial female), and Laodan (old lady).

Jing: Jing in Peking Opera refers to roles with distinctive facial features, commonly known as “painted face.” They are characterized by the use of various colors to outline patterned facial makeup, portraying characters with bold, extraordinary, and heroic personalities. These characters require broad and powerful vocal delivery, robust singing, and sharp and distinct movements and gestures, with large color patches and grand gestures.

Mo: Mo in Peking Opera refers to middle-aged male roles. In Northern Zaju, Mo was also called “Mo Ni” or “Mo Ni Se,” which generally referred to supporting roles. They served as narrators, introducing the plot and the main theme of the play, and played secondary characters with lower social status.

Chou: Chou refers to comedic roles that engage in banter and are often portrayed as foolish and confused characters. They wear facial makeup with lines drawn on the bridge of the nose and around the eyes, often playing humorous and satirical roles. Chou roles usually emphasize clear and fluent spoken lines over singing. They can be divided into Wenchou (comic roles with spoken lines) and Wuchou (comic roles with martial skills).

Chinese opera mask characters

Guan Yu

The red Peking Opera facial makeup represents a loyal and heroic character, primarily representing the character of Guan Yu.

Dou Erdun

The blue Peking Opera facial makeup represents a strong and valiant character, primarily representing the character of Dou Erdun.

Bao Zheng

The black Peking Opera facial makeup represents an upright, selfless, and resolute character, primarily representing the character of Bao Zheng.

Cao Cao

The white Peking Opera facial makeup represents a cunning, suspicious, and sinister character, primarily representing the character of Cao Cao.

Wu Tianqiu

The green Peking Opera facial makeup represents a tenacious and irritable character, primarily representing the character of Wu Tianqiu.

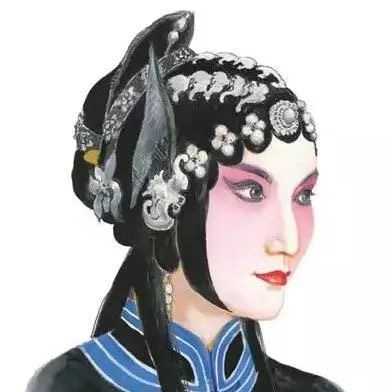

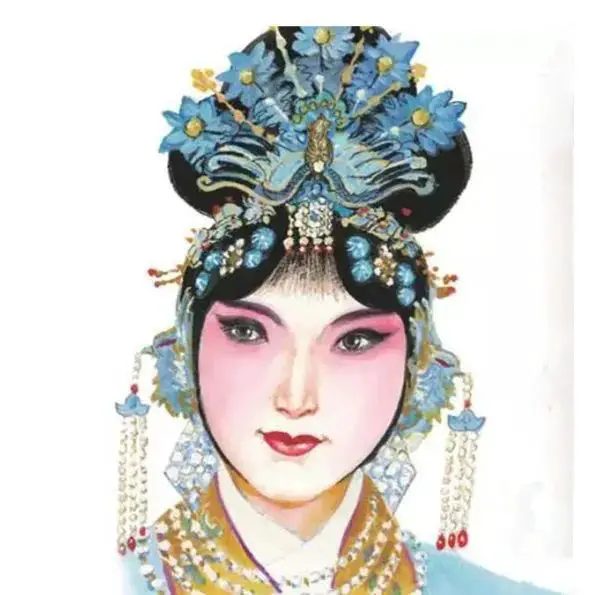

Chinese opera headdress meaning

Headgear: Refers to the various hats worn by characters in Peking Opera. Based on different roles, personalities, and identities, headgear can be divided into four categories: crowns, helmets, hats, and kerchiefs.

Crowns: Mostly worn by emperors and nobles as ceremonial hats.

Helmets: Worn by military officers and generals.

Hats: The most versatile category, including formal ceremonial hats for officials and common hats for daily life.

Kerchiefs: Worn by characters in casual attire.

Head Ornaments: Refers to all kinds of makeup and decorations on the heads of female characters (Dan roles) in Peking Opera. They can be classified into soft and hard types.

Soft Head Ornaments: Including hair curtains, nets, hair pads, hairpins, large hair pieces, and water veils.

Hard Head Ornaments: Such as ornaments with jade, water diamonds, and silver ingots.

Artistic Characteristics:

Baiyutang Peking Opera stage art, in literature, performance, music, singing, percussion, makeup, and facial painting, has formed a set of standardized and regulated styles and rules through the long-term stage practices of countless performers. It is a rich and strictly regulated artistic means for creating stage images.

Without mastering these styles, it is impossible to achieve the artistic creation of Peking Opera. As it entered the palace in its early stages of development, Peking Opera’s growth differs from local opera forms. It demands a wider range of themes to portray, a greater variety of character types to shape, and more comprehensive and complete artistic skills. Accordingly, the aesthetic requirements for creating stage images are also higher. However, this has also led to a reduction in its folk and local characteristics, making its simple and robust style relatively weakened.

Chinese opera costume

Traditional Chinese opera costumes are commonly referred to as “Xing Tou” in Chinese. They belong to the “Freehand Artistic System” and are a form of artistic costumes refined from everyday clothing, which is somewhat similar to historical attire but also distinct as an artistic representation of clothing. Traditional opera costumes rely on the aesthetics of physical appearance and match the programmatic, virtual, and hypothetical nature of traditional opera performance. Their highest aesthetic pursuit is to vividly express the character’s emotions and sentiments. These costumes possess the beauty of programmatic design, rhythmic patterns, decoration, and symbolism.

The “Xing Tou” plays an artistic role in shaping the external image of characters and reflects their identities, ages, and occupations. There are various types of “Xing Tou” based on different roles and occasions. Some examples include:

“Kai Chang” (Open Robe): Used for high-ranking military officers and ministers in non-ceremonial occasions, as well as certain leading characters in the play to emphasize their imposing presence, such as chieftains and skilled warriors.

Official Robe: Worn by mid-level civil officials (occasionally used for specific situations, like newly appointed top scholars or grooms in wedding scenes). It is derived from the official robe of the Ming Dynasty with a wide collar and narrow sleeves. The main difference is the absence of embroidered patterns, and it is made of plain colored silk fabric. The embroidered patch on the chest and back has flying birds and rising sun and sea waves. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the embroidered patches denoted official ranks and positions. In Peking Opera, the “embroidered patches” on official robes serve as artistic symbols.

Mian (Court Dress): A ritual dress used by characters with noble and high-ranking status.

These costumes have distinctive characteristics. They are highly decorative and inherit the tradition of pursuing a sense of artistic conception and expressing spiritual meaning through clothing. The long robes and wide sleeves of “Xing Tou” add solemnity, while the elaborate decorative patterns symbolize specific meanings. Another characteristic is their high flexibility, as they are not tied around the waist and can be moved freely to express emotions. The use of exaggerated water sleeves enriches the movements and conveys the characters’ emotions.

Materials used for “Xing Tou” are typically fine satin, and the main patterns are dragon and “Mangshui” (sea water and river teeth). Colors are vivid and strongly contrasted to create a brilliant and magnificent effect. The choice of colors also has specific meanings according to the character’s type. Embroidery plays a significant role in the design, with various techniques such as colorful velvet embroidery, flat gold and silver embroidery, and circular gold velvet embroidery.

Overall, traditional Chinese opera costumes are not only an artistic means to shape character appearances but also convey cultural and symbolic significance through their aesthetic beauty and rich symbolism.

Chinese opera hairstyle

The beauty of Chinese opera lies not only in its performance art but also in the exquisite costumes, with headwear being particularly captivating. Opera headwear includes the hairstyles of characters and various ornaments worn on the head. It serves as a means of expression for actors’ performances and dances and is an essential component of character representation.

“Yin Ding” (Silver Ingot Headwear): Made of silver-plated copper, it is a semi-circular ball-shaped ornament, also known as “Silver Foam Headwear.” Due to its simplicity and elegance, it is often used for portraying poor young women in the “Qingyi” role, symbolizing their impoverished life. Characters wearing “Yin Ding” headwear can achieve personalized artistic hairstyles by altering the combination of head ornaments.

“Shui Zuan” (Water Diamond Headwear): Made of high-grade glass imitating diamonds, known as “water diamonds,” it is commonly used by female characters in the “Dan” role to highlight their youthful beauty and vibrant personalities. Young girls, young women, or middle-aged women can wear “Shui Zuan” headwear.

“Dian Cui” (Jade Inlaid Headwear): Made of rare emerald green feathers pasted on a metal base, forming colorful patterns, it is the highest-grade type of headwear. Characters wearing “Dian Cui” headwear represent a higher social status, with their fathers or husbands being high-ranking officials in the imperial court. Royal consorts in the palace also wear “Dian Cui” headwear when not wearing a crown.

“Zhua Ji Tou” (Claw Bun Headwear): A traditional large bun hairstyle with a fan-shaped bun at the top, wrapped with red hair thread or silk thread (about 30 centimeters wide). It is commonly used for young female roles such as flower girls, young women, and maids, portraying characters like Sun Yujiao in “Pick Up the Jade Bracelet” or Chunxiang in “A Dream in the Garden.”

“Qi Zhuang Tou” (Banner Dress Headwear): It is an artistic hairstyle that matches the “Qi Zhuang” costume, with a horizontal long bun forming a straight line, resembling the character “一” (one). It was used on the Peking Opera stage in the mid-Qing dynasty. After artistic modifications, it became specialized for portraying noble and middle-aged women from “foreign lands” in traditional plays. The main styles include “Da Liang Ba Tou” and “Qi Tou Dian Zi,” with “Xiao Liang Ba Tou” used for maids. The “Qi Tou Zuo” headwear is used for characters like Hu Ayun in “Su Wu Shepherding Sheep.”

“Gu Zhuang Tou” (Ancient Costume Headwear): It is a hairstyle for female roles in Peking Opera. The temples are still covered with hairpieces (sometimes without). The headwear is a wig, and the human hair is styled in various ways. The hairpieces are not tied at the back of the head. Some are styled on the top of the head, some are on one side, and others are parted in the middle to form a “吕” (Lü) or “品” (Pin) shape.

Around 1915, Mei Lanfang drew inspiration from ancient paintings of court ladies to change the traditional “big head” hairstyle and created the “Gu Zhuang Tou” hairstyle that closely resembles the original ancient women’s hairstyles. This innovation contributed to the diverse representation of ancient women’s hairstyles on the opera stage and early costume films. The influence of this hairstyle continues to this day.

Chinese opera makeup

The key points of Chinese theatrical makeup include the following:

Base Makeup: Unlike regular makeup, Peking Opera performers use foundation cream as a base to better conceal their natural skin color.

Red Cheek Makeup (Gao Zhuang): Peking Opera makeup does not involve contouring but instead uses red cream blush to create a natural flush on the eyelids, nose bridge, and cheekbones, enhancing facial contours and setting the makeup.

Pink Cheek Makeup (Fen Zhuang): Pink powder blush is applied extensively around the eyes to create a more natural blush.

Eye Makeup: Thick, all-around black eyeliner is used with an upward flick at the end to create an almond-shaped eye, resembling the shape of a red-crowned crane’s eye.

Eyebrow Makeup: The eyebrows are drawn with black pencil in a willow leaf shape, upward and delicate, giving a spirited expression.

Lip Makeup: Peking Opera’s lip makeup requires the use of bright red lipstick to outline a plump and small lip shape within the natural lip contour.

Before the formation of Chinese opera, two makeup methods existed in various performance arts: mask makeup and painted makeup. As cultural pursuits evolved, makeup in performing arts also became diversified.

Mask Makeup:

Mask makeup originated from primitive ritual dances, particularly “Nuo Dance,” which had a close relationship with the development of later theatrical performances. Nuo Dance involved wearing masks, transforming performers into gods, historical figures, and various fantastic creatures, expressing worship to deities, prayers to ancestors, and the exorcism of demons and evil beings.

Painted Makeup:

Painted makeup is the primary makeup method in Chinese opera, which incorporates the advantages of mask makeup. The makeup in Peking Opera can be classified into three types: beautifying makeup (Jun Ban) for the Sheng (male) and Dan (female) roles, character makeup (Lian Pu) for Jing (painted face) and Chou (clown) roles, and emotional makeup (Bian Lian) for face-changing techniques.

Beautifying Makeup:

Beautifying makeup is used for the Sheng and Dan roles, often referred to as “Jun Ban,” which is relatively simpler compared to the elaborate patterns used for Jing and Chou roles. In the early days, Sheng and Dan makeup was more understated, as it was suited to performances under natural lighting conditions. However, with the introduction of stage lighting in the late Qing dynasty, makeup colors became more intense, transitioning from powder pigments to oil paints. Sheng and Dan makeup may not have intricate patterns, but they still feature decorative elements. For the Dan role, there are pasted patterns applied to the forehead, temples, and sideburns, enhancing facial contours and beautifying face shapes. The use of colors and techniques may vary based on the age, roles (civil or martial), and circumstances of the characters in the play.

Character Makeup:

Character makeup is used for Jing and Chou roles, employing the use of facial masks. The masks draw inspiration from the folk art styles popular in the Qing dynasty and have become an integral part of stage art. Early facial masks were relatively simple, with the main focus on the eyebrows and eyes. The variety of mask designs expanded during the early Qing dynasty. In Peking Opera, facial masks borrowed from the experiences of various regional opera genres, forming a relatively comprehensive and systematic system.

In Qing dynasty paintings, facial masks for the Jing roles already included multiple types, such as painted faces (Mo Lian), carved faces (Gou Lian), brushed faces (Mo Lian with light strokes), and worn-out faces (Po Lian). These different styles were extensively used for official roles, heroes, and supernatural beings. The colors used for facial masks include red, yellow, blue, white, black, purple, green, and silver, each representing specific symbolic meanings and serving particular purposes. For instance, red symbolizes loyalty, bravery, and uprightness, while water-white denotes cunning and suspicion. Gold and silver are often used for supernatural beings.

Character makeup for the Chou roles involves drawing a white foundation between the nose bridge and eye sockets, contrasting with the large face (Da Hua Lian) makeup, giving it the nickname “Xiao Hua Lian” (small face). Based on the character’s role, personality, and technical characteristics, Chou makeup can be further divided into civil (Wen Chou) and martial (Wu Chou) types.

Emotional Makeup:

Emotional makeup is a form of Chinese theatrical makeup used for face-changing techniques. It aims to depict sudden changes in the character’s emotions, such as shock, despair, anger, etc. This technique was first used for supernatural roles, even as early as the Ming dynasty. Initially, actors would change their makeup backstage. In later times, face-changing became a performance art, and many regional opera genres adopted it, with Sichuan Opera being the most famous. Face-changing involves quick and seamless movements, closely linked to the character’s emotional shifts, without leaving any visible traces. In improving face-changing techniques, artists like Kang Zilin, Wei Xianglin, and Sun Decai made significant contributions.

famous Chinese opera singers

Mei Lanfang: Mei Lanfang was a renowned Peking Opera performer known for his exceptional skills in playing female roles (Dan). He was born in 1894 in Beijing and was considered one of the greatest Peking Opera artists. Mei Lanfang’s performances and contributions helped promote Chinese opera internationally.

Chen Suzhen: Chen Suzhen, also known as Chen Su Zhen or “Yueju Meilanfang,” was a prominent Yue Opera performer. She was a master of the Qingyi (青衣) and Huadan (花旦) roles in Yue Opera. Chen Suzhen was known for her unique style and innovation in the Yue Opera genre.

Xin Fengxia: Xin Fengxia was a celebrated Pingju performer known for her roles as Qingyi and Huadan. She was born Yang Shumin in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, around the 1920s. Xin Fengxia was a pioneer in Pingju, incorporating elements of classical dance and mime into the traditional art form.

Yuan Xuefen: Yuan Xuefen, also known as Yuan Xue Fen, was a famous Yue Opera artist specializing in the Zhengdan (正旦) roles. She was born in 1918 in Shengxian, Zhejiang province. Yuan Xuefen was highly regarded for her versatile skills and contributions to Yue Opera.

Yan Fengying: Yan Fengying was a renowned Huangmei Opera performer, known for her skills in playing the Qingyi and Huadan roles. She was born in 1930 and made significant contributions to the development and promotion of Huangmei Opera.

Please note that some names and details in the original text may have slight variations in English translation. Also, the list above is not exhaustive, and there are many other talented Chinese opera singers in various regional opera genres.

Chinese opera history

Chinese theater has a long history, beginning from ancient times until the Ming and Qing dynasties, during which various theatrical genres developed. It can be broadly divided into several stages:

I. Pre-Qin to Han and Wei Dynasties – The Emergence of Performing Artists:

During this period, performers known as “优” (Yōu) or “伶” (Líng) initially referred to musicians and were commonly called “优伶” (Yōu Líng). The Kangxi Dictionary explains them as musicians, and they were often associated with music officials. They provided entertainment and amusement but didn’t perform on formal stages like in later times. Historical records mentioned various performers, such as “优孟者” (Yōu Mèng), who was known for his wit and satire, and “优旃者” (Yōu Zhān), a talented jester. They entertained people and sometimes used humor to deliver subtle criticism.

II. Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties Periods – The Blossoming of Drama:

During the Tang Dynasty, the theater began to flourish, and official music and dance performances were established. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang was particularly fond of performing arts and even had his own troupe called “梨园” (Lí Yuán). During this period, “滑稽戏” (Huájī Xì) or comedic plays also emerged.

III. Song and Yuan Dynasties – The Development of Drama:

During the Song Dynasty, theater continued to evolve, and “话本” (Huà Běn) or storytelling scripts became popular. These scripts formed the basis for performances, and the actors began to specialize in different roles. The development of the southern and northern theater traditions took place, leading to further diversification of theatrical performances.

IV. Ming and Qing Dynasties – The Rise of Chuanqi (传奇):

In the Ming Dynasty, “传奇” (Chuánqí), or drama, became prominent. Various regional operatic styles emerged, such as “南戏” (Nán Xì) and “北曲” (Běi Qū). The “四大声腔” (Sì Dà Shēng Qiāng) or Four Major Melodic Styles emerged, representing different regional vocal styles. In the Qing Dynasty, “京剧” (Jīng Jù) or Peking Opera rose to prominence and eventually became the dominant form of Chinese theater.

Each stage in Chinese theater history brought its unique forms of performance, storytelling, and artistic expression, shaping the rich and diverse theatrical tradition of China.

where did Chinese opera originate?

Beijing Opera – Anhui Province:

Beijing Opera, formerly known as Peking Opera, is one of the five major opera genres in China. Its stage settings emphasize artistic representation, and the predominant vocal styles are Xi and Huang. It is renowned for its combination of singing, acting, and acrobatics and is considered one of China’s national treasures and one of the three major Chinese theatrical forms.

Huizhou Opera served as the precursor to Beijing Opera. From the 55th year of the Qianlong reign of the Qing Dynasty (1790), performance troupes from Anhui, including Sanqing, Sixi, Chuntai, and Hechun, started performing in the south. These four troupes gradually made their way to Beijing and collaborated with Hubei’s Han diao performers.

They adopted certain elements from Kunqu and Qinqiang, absorbed some local folk tunes, and through continuous dissemination and fusion, eventually formed Beijing Opera. During the Qing Dynasty, Beijing Opera rapidly developed in the imperial court and reached unprecedented prosperity during the Republican era.

Beijing Opera originated in Beijing but spread throughout China, becoming an important medium for introducing and promoting traditional Chinese artistic culture. In November 2010, Beijing Opera was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Yue Opera – Zhejiang Province:

Yue Opera, also known as Shaoxing Opera or Yuju, is China’s second-largest opera genre, often referred to as the “Second National Opera” or the “most popular local opera.” It is one of the five major opera genres in China, following Beijing Opera, Yue Opera, Huangmei Opera, and Pingju. It originated in Shengzhou, Zhejiang, and later developed in Shanghai, gaining popularity nationwide and spreading worldwide. Throughout its development, it absorbed elements from Kunqu, Peking Opera, and Shao Opera, and underwent a transition from male roles to female roles.

Yue Opera is known for its lyrical and expressive singing, with a clear and melodious voice. Its performances are elegant and graceful, reflecting the charm of the Jiangnan region. The main themes often revolve around romantic stories between talented scholars and beautiful ladies, and it has various artistic schools, including the recognized “Thirteen Schools.”

Yue Opera is popular in regions such as Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Anhui, as well as parts of Beijing and Tianjin. During its heyday, it had professional troupes across the country, with a strong presence in the North and South.

Huangmei Opera – Anhui Province:

Huangmei Opera, originally known as Huangmei Diao or Caicha Xi, originated in Huangmei County, Hubei, and developed in Anqing, Anhui. It is also a major local opera in Anhui Province. It spread to provinces such as Hubei, Jiangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Hong Kong, and Taiwan and gained widespread popularity.

Huangmei Opera’s origins can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty when Huangmei’s tea-picking songs were popular. Through the development of Song Dynasty folk songs and the influence of Yuan Dynasty variety shows, local theatrical performances gradually took shape. By the Ming and Qing periods, Huangmei Opera further prospered in Huangmei County.

Huangmei Opera evolved from Caicha Xi to Huangmei Opera. It absorbed elements from various traditional regional operas, and later on, it was also known as Huangmei Xi or Huangmei Bangzi. Its distinctive singing style features a clear and melodious voice, and it is particularly known for its genuine and vivid performances. One of its most famous songs, “Tianxian Pei” (Heavenly Maiden Consort), has made Huangmei Opera famous both domestically and internationally.

In May 2006, Huangmei Opera was inscribed on China’s first national intangible cultural heritage list.

Pingju – Hebei Province:

Pingju, also known as Ping Opera, is one of the five major opera genres in China and a major local opera in Hebei Province. It originated in the southern regions of Hebei, and its singing style is characterized by a high-pitched and lively vocal style. It is traditionally performed with wooden clappers and gongs, and the performances involve singing, acting, and acrobatics.

Pingju, like other traditional Chinese opera genres, has a long history, dating back to ancient times. During the Qing Dynasty, it was officially recognized as a genre and experienced significant development.

Pingju mainly flourishes in North and Northeast China, including Hebei, Tianjin, and parts of Beijing. During its peak, Pingju was popular in various regions throughout the country, and there were numerous professional and amateur troupes.

In May 2006, Pingju was inscribed on China’s first national intangible cultural heritage list.

Yu Opera – Henan Province:

Yu Opera, also known as Henan Opera or Yuju, is the largest local opera in China and ranks first among all local opera genres in the country. According to statistics from China’s cultural authorities in 2006, there were 163 state-owned professional Yu Opera troupes, making it the opera genre with the most troupes and practitioners, and it became one of the top three Chinese opera genres.

Yu Opera was initially called “Henan Bangzi” or “Henan Gaodiào.” In the early days, the actors used their natural voices in performances. When starting or concluding a performance, they used a false voice to raise the pitch of the ending phrase “福” (fú), which led to its nickname “Henan Fu” (河南福). Later on, it was named Yu Opera since the People’s Republic of China is abbreviated as “豫” (yù), the name of Henan Province.

Yu Opera is renowned for its vigorous and expressive singing, with a moderate tone, smooth vocal lines, clear enunciation, rich charm, vivid performances, and the ability to convey characters’ inner emotions. It enjoys widespread popularity among people from various walks of life. Its musical accompaniment is based on Zhuo Bangzi, which is why it was initially called “Henan Bangzi.”

Besides Henan Province, there are professional Yu Opera troupes in Hubei, Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, Beijing, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. During its peak, Yu Opera was popular throughout the country, except for a few provinces and regions.

In May 2006, Yu Opera was inscribed on China’s first national intangible cultural heritage list.

when did Chinese opera start?

The formation of Chinese opera can be traced back to the Qin and Han dynasties, but the process was quite lengthy, and it wasn’t until the Song and Yuan periods that it began to take shape. Mature opera can be considered to have originated from Yuan Zaju, and it continued to develop and mature during the Ming and Qing dynasties, eventually entering the modern era. Over the course of more than 800 years, it has thrived and remained resilient, giving rise to over 360 different opera genres. During its long and evolving development, Chinese classical opera went through four fundamental forms: Song and Yuan Nanxi, Yuan Zaju, Ming-Qing Chuanqi, Qing regional operas, and modern and contemporary operas.

why was Chinese opera invented?

- The formation of Chinese opera originated from primitive singing and dancing, and it gradually evolved and integrated into a complete form of performing arts during the Han, Tang, Song, and Jin dynasties. It mainly emerged from the combination of three different art forms: folk singing and dancing, storytelling, and humorous skits.

- In ancient villages where clans settled, primitive singing and dancing emerged, and as the clans grew stronger, the singing and dancing also developed and improved. Many ancient rural areas still preserve long-standing traditions of singing and dancing, such as “Nuo opera.” At the same time, new forms of singing and dancing, such as “Shehuo” and “Yangge,” were born to meet the spiritual needs of the people. It was these performances that nurtured skillful folk artists and gradually led to the development of opera.

- In the mid-12th to early 13th century, professional and commercial performing groups emerged, and Song Zaju and Jin Yuanben plays reflected the lives and viewpoints of the urban populace. Works like “The Injustice to Dou E” by Guan Hanqing, “Autumn in the Han Palace” by Ma Zhiyuan, and “Revenge of the Orphan of the Zhao Family” were created during this period. It was a prosperous era for the stage of Chinese opera.

what does Chinese opera represent?

Chinese opera represents a rich and diverse form of traditional performing arts that has been an integral part of Chinese culture for centuries. It encompasses various regional styles and genres, each with its unique characteristics and performance techniques. Chinese opera is not merely entertainment but also serves as a reflection of the historical, social, and cultural aspects of China. Here are some key aspects that Chinese opera represents:

Cultural Heritage: Chinese opera is a significant cultural heritage of China, passed down through generations. It embodies the traditional values, beliefs, and aesthetics of the Chinese people.

Historical Narratives: Chinese opera often features historical stories, myths, and legends that portray the events, heroes, and heroines of ancient times. Through these narratives, it provides insights into the historical events and societal values of various periods.

Artistic Expression: Chinese opera combines music, singing, acting, and acrobatics, creating a unique form of artistic expression. Performers use intricate hand gestures, facial expressions, and body movements to convey emotions and portray characters.

Symbolism and Costumes: The elaborate and colorful costumes worn by the opera characters represent different social statuses, professions, and personalities. They also convey symbolic meanings, enhancing the visual impact of the performance.

Regional Diversity: Different regions in China have their own distinctive styles of opera, such as Peking Opera, Cantonese Opera, Shaoxing Opera, and more. Each regional opera has its own repertoire and performance techniques, reflecting the local customs and traditions.

Social Commentary: Chinese opera often incorporates social commentary and moral lessons, addressing contemporary issues and critiquing social norms. It has been a means of expressing dissent and advocating for change throughout history.

Community and Identity: Chinese opera has been a source of community cohesion, bringing people together for shared cultural experiences. It plays a crucial role in maintaining and reinforcing Chinese identity both within China and among overseas Chinese communities.

Rituals and Festivals: Chinese opera has been an integral part of religious rituals and festive celebrations. It is commonly performed during traditional festivals and ceremonies to invoke blessings and express gratitude to deities and ancestors.

Overall, Chinese opera is a multifaceted art form that represents the essence of Chinese culture, history, and artistic expression, and it continues to be appreciated and celebrated as an essential part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.

what does blue mean in Chinese opera?

Blue color represents strong, valiant, and cunning character traits in Chinese opera. One typical representative character is Dou Erdun.

Dou Erdun is a renowned character in Chinese Peking opera, and he is one of the characters portrayed in blue costumes. He embodies a combination of strength, bravery, and cunning in the plot. The blue costume emphasizes his resolute personality and courageous spirit.

Dou Erdun is often described as tall and robust, with a determined and stern expression. He wears a blue costume, symbolizing his unwavering qualities. The blue robes complement his steadfast gaze and confident demeanor. Through unique stage movements and vocal performance, actors vividly bring the character of Dou Erdun to life before the audience.

As a heroic figure, Dou Erdun often demonstrates bravery and decisiveness in the storyline. He may be a military general on the battlefield or a righteous defender of his homeland. His firmness and determination make him a role model and inspiration in people’s hearts. The design of the blue costume underscores his inner determination and pursuit of justice.

In addition to his strength and valor, Dou Erdun is often depicted as cunning and exceptionally wise. He remains composed in complex situations, devising clever plans and making wise decisions. This blend of intelligence and fortitude makes him a crucial figure in the plot.

The use of blue color in the character of Dou Erdun serves to highlight his distinctive traits and plays a significant visual role in the stage performance. Through the implied meanings of color and the actors’ portrayal, the audience can easily understand and connect with the character, becoming fully engaged in the storyline.

In conclusion, blue color in Chinese opera represents strong, valiant, and cunning character traits. In the character of Dou Erdun, the blue costume accentuates his bravery, decisiveness, and intelligence, making him a beloved and admired heroic figure in Peking opera. Through such vivid character portrayals, Chinese opera continues to convey its rich cultural significance and captivate audiences with its unique charm on the stage.

what does purple mean in Chinese opera?

In Chinese opera, the color purple generally represents characters with strong, steady, composed, solemn, and righteous qualities. It can also symbolize characters with an unattractive or ugly appearance.

In Chinese opera, purple plays an important role in costume design as it not only highlights the personality traits of the characters but also expresses their appearance and inner temperament.

Firstly, purple is used to portray upright and determined characters. These characters are usually loyal to their missions and beliefs, fear no difficulties, and forge ahead bravely. They possess stable and composed personalities and can remain calm and cool-headed in the face of adversity. These character traits are often depicted through the use of purple attire, enabling actors to better display the resolute and steady nature of their roles.

Secondly, purple is often employed to represent characters with a strong sense of justice. These characters uphold fairness and righteousness, courageously defending justice and public interests. They have firm and righteous personalities and never compromise on matters of injustice. Purple costumes make these characters appear more dignified and noble, while also highlighting their inner sense of justice and unwavering beliefs.

Additionally, purple can be used to emphasize certain physical features of characters. In Chinese opera, some ugly or evil characters are often dressed in purple attire to accentuate their unattractiveness and negative personality traits. This use of color helps the audience easily identify the good and evil sides of the characters.

In summary, purple holds multiple meanings in Chinese opera. It is not merely a color but also an essential means of expressing the personalities and images of the characters. Through the use of purple, opera performers can better convey the characters’ strong and righteous qualities, enabling the audience to deeply understand and resonate with them. Additionally, purple enhances the visual effects of the characters, making the stage performances more vibrant and lively. Whether for positive or negative characters, purple adds depth to their images and makes Chinese opera more diverse and captivating.

what does white mean in Chinese opera?

White color in Chinese Beijing Opera is divided into two types: “粉白” (fěn bái) and “油白” (yóu bái). In Beijing Opera, the use of white-colored facial makeup is often associated with portraying negative characters and villains. For instance, the cunning and treacherous character of Cao Cao in the Three Kingdoms opera is depicted with a “粉白” (fěn bái) face, symbolizing his deceitful and suspicious nature. Additionally, white facial makeup is also used for characters such as elderly heroes, generals, monks, eunuchs, and others who possess virtuous or distinguished traits. This color choice accentuates their wisdom, composure, and sense of justice.

In traditional Chinese Beijing Opera, facial makeup plays a crucial role in conveying the personality and temperament of characters. The usage of white color in facial makeup helps audiences to quickly identify the nature of a character. Villains and antagonistic figures with “粉白” (fěn bái) faces appear deceitful and untrustworthy, while characters with “油白” (yóu bái) faces, such as wise heroes and virtuous individuals, are seen as composed and upright.

Beijing Opera is renowned for its intricate and artistic facial makeup, enhancing the performance and enabling the audience to better understand the personalities and emotions of the characters. Through the skilled application of different facial makeup colors, Beijing Opera brings a vibrant and diverse array of characters to life on the stage, making it an integral part of China’s traditional theatrical arts.

what does black mean in Chinese opera?

Originally, black facial makeup in Chinese traditional culture was used to represent the character’s skin color. However, over time, black has gradually acquired symbolic significance. In the context of Beijing Opera performances, black facial makeup is typically used to portray characters who are upright, selfless, principled, straightforward, and courageous.

One such example is the historical figure Bao Gong, a renowned official known for his impartiality and dedication to justice, earning him the affection of the people. In his portrayal, the black facial makeup signifies a darker complexion rather than fair skin. As Bao Gong’s image gained admiration, black facial makeup became a symbol representing selflessness and unwavering integrity.

In modern society, the meaning of black facial makeup has further expanded and extended. In films, novels, and other literary works, black facial makeup is often used to represent characters who are courageous, resilient, and unwavering in their pursuit of justice. These characters are typically straightforward, fearless, and unyielding in the face of difficulties and challenges. As a result, black facial makeup has become a symbol for these individuals, expressing people’s admiration and respect for their character and qualities.

what does pink mean in Chinese opera?

In traditional Chinese culture, pink is generally considered a gentle and soft color, often used in female clothing and decorations. In Beijing Opera facial makeup, pink represents elderly characters with loyal and virtuous traits, such as the role of Lian Po.

Beijing Opera facial makeup is a unique way of makeup that conveys the character’s personality and qualities through colors and patterns. Pink is a relatively special color in Beijing Opera facial makeup and is usually used to represent elderly female characters, such as mothers-in-law or virtuous women. These characters are typically portrayed as virtuous, gentle, and benevolent, gaining much appreciation from the audience.

Moreover, pink is also used in Beijing Opera facial makeup to represent loyal and kind-hearted characters, such as the wives of famous generals like Guan Yu or Meng Liang. These characters are often depicted as loyal, brave, and kind, earning admiration from the audience.

In summary, pink is a distinctive color in Beijing Opera facial makeup, representing elderly and virtuous characters, as well as loyal and kind-hearted ones. Through the combination of colors and patterns, the facial makeup enhances the vividness and characterization of the Beijing Opera performances.

what does green mean in Chinese opera?

Green is a common color in nature, and in Beijing Opera facial makeup, the green face is often used to represent courageous, impulsive, and hot-tempered characters. These characters typically possess strong personalities and impulsive tendencies, showing fearlessness and sometimes even barbarism. They usually play important roles in the opera, such as generals and brave warriors.

Additionally, some bandit-like characters, who rule the mountains and forests, are depicted with green facial makeup. These characters are often portrayed as bold, fearless, and resolute, disregarding conventions and showing great courage and astuteness. They usually play antagonistic roles in the opera, such as bandits and mountain thieves.

Green facial makeup shares a similar purpose with black facial makeup, as both are used to convey the character’s personality and qualities. However, black facial makeup emphasizes the character’s fairness, selflessness, and uprightness, while green facial makeup focuses more on portraying the character’s courageous, impulsive, and hot-tempered traits.

In conclusion, green facial makeup is a distinctive color in Beijing Opera facial makeup, representing courageous, impulsive, and hot-tempered characters, as well as some bandit-like figures. Through the combination of colors and patterns, the facial makeup enhances the vividness and characterization of the Beijing Opera performances.

what does red mean in Chinese opera?

Red is a highly significant color in Chinese culture, representing positive qualities such as passion, warmth, justice, and loyalty. In Beijing Opera facial makeup, the red face is commonly used to depict characters who are upright, loyal, courageous, and often portrayed in positive roles.

Initially, red facial makeup was simply used to indicate the character’s skin color, as in Chinese traditional culture, red is considered a color that brings good luck and wards off evil. Many characters with red or black skin are often portrayed as loyal, brave, and righteous, leading to the use of red to symbolize loyalty and courage for virtuous generals and divine immortals.

Furthermore, red facial makeup can also represent characters who are passionate, zealous, and possess a strong sense of justice. These characters typically have firm beliefs and strong determination, courageously pursuing their dreams and goals. They often play positive roles in the opera, such as heroes, knights, and loyal ministers.

In conclusion, red facial makeup is a commonly used color in Beijing Opera facial makeup, representing characters who are upright, loyal, courageous, and frequently depicted in positive roles. Through the combination of colors and patterns, the facial makeup enhances the vividness and characterization of Beijing Opera performances.

what does yellow mean in Chinese opera?

Yellow is a unique color in Beijing Opera facial makeup and is often used to represent characters who are brave and violent or have wicked and cunning traits. Yellow facial makeup is commonly used to depict fierce and impulsive characters who possess strong personalities and fearlessness, sometimes even exhibiting a savage nature.

Additionally, yellow facial makeup can also be used to represent evil and treacherous characters. These characters often harbor malicious intentions and employ ruthless means to pursue their own interests. They typically play antagonistic roles in the opera, such as treacherous ministers or tyrannical oppressors.

In summary, yellow facial makeup is a distinctive color in Beijing Opera facial makeup, representing characters with bold and violent traits, as well as evil and cunning characters. Through the combination of colors and patterns, the facial makeup enhances the vividness and characterization of Beijing Opera performances.

why is Chinese opera high-pitched?

There are several reasons for the high-pitched nature of Chinese opera.

Firstly, most Chinese operas use high-pitched singing, which makes the voices sound bright and soaring. Additionally, the vocal range in Chinese opera is typically wide, requiring actors to transition between different pitch levels effortlessly, creating a dynamic and impassioned vocal performance.

Secondly, Chinese opera emphasizes distinct characterizations, with each character having specific singing styles and performance techniques. For instance, male roles (wusheng) often use forceful and high-pitched singing, while female roles (huadan) tend to use more gentle and melodious singing. This differentiation of roles demands the use of high-pitched voices to portray each character’s unique traits effectively.

Furthermore, Chinese opera performances are often accompanied by dance, martial arts, and other forms of expression that require agile and powerful movements. This requires actors to project their voices with a high-pitched and forceful tone to complement these performance elements.

In conclusion, the high-pitched nature of Chinese opera is the result of multiple factors, including the style of singing, character differentiations, and the need to match other performance forms. The interplay of these elements creates a distinctive performance style, enhancing the artistic and aesthetic value of Chinese opera.

why is Chinese opera important?

Chinese opera is of great significance as it represents an essential part of traditional Chinese culture, embodying the spirit and soul of Chinese heritage. The following are some key reasons for the importance of Chinese opera:

Preserving historical culture: Chinese opera boasts a long history, rich cultural connotations, and historical information. Through performances and appreciation of Chinese opera, people can better understand Chinese history and culture, as well as inherit and promote the excellent traditional culture of the Chinese nation.

Upholding social morality: Chinese opera emphasizes moral standards and values, such as loyalty, filial piety, friendship, love, and more. Through performances and appreciation of Chinese opera, people can better comprehend these moral standards and values, and uphold and promote social morality.

Artistic expression: Chinese opera is a unique art form that incorporates various artistic elements, including music, dance, drama, poetry, and more, possessing high artistic and aesthetic value. Through performances and appreciation of Chinese opera, people can enjoy the beauty and pleasure brought by this distinctive art form.

Spiritual and cultural enrichment: Chinese opera is a popular cultural form deeply loved and welcomed by the people. Through performances and appreciation of Chinese opera, people can enrich their spiritual and cultural life, fostering a greater appreciation for life and hope for the future.

In conclusion, Chinese opera is an indispensable part of traditional Chinese culture, carrying significant historical, cultural, artistic, and spiritual values. It represents an important cultural heritage that cannot be overlooked in Chinese culture.

Chinese Opera and the yin yang

Chinese opera and the concept of Yin and Yang are both significant elements in traditional Chinese culture. Let’s explore how they are related:

Yin and Yang in Chinese Opera:

Yin and Yang are fundamental concepts in Chinese philosophy, representing the dualistic nature of the universe. Yin symbolizes darkness, passivity, and the feminine aspect, while Yang represents brightness, activity, and the masculine aspect. These two complementary forces are interconnected and exist in a state of constant balance and change.

In Chinese opera, the concept of Yin and Yang is often reflected in various aspects of the performance:

Characters: Traditional Chinese opera often features characters that embody the principles of Yin and Yang. For example, the male characters, such as the martial heroes, generals, and scholars, are associated with Yang, representing courage, strength, and intellect. On the other hand, female characters, like virtuous women and graceful dancers, are associated with Yin, representing beauty, elegance, and softness.

Costume and Makeup: The costumes and makeup used in Chinese opera are also designed to reflect the concept of Yin and Yang. The male characters typically wear bold and vibrant colors, representing Yang, while female characters wear softer and more delicate colors, representing Yin. The elaborate facial makeup, called “face painting” or “facial makeup” (脸谱 liǎnpǔ), also uses contrasting colors to emphasize the duality of characters.

Movements and Gestures: The physical movements and gestures of the actors in Chinese opera often follow the principles of Yin and Yang. Male characters tend to have powerful and assertive movements, embodying Yang, while female characters have graceful and refined movements, embodying Yin.

Yin and Yang in Symbolism and Themes:

In addition to the direct representation of Yin and Yang in characters and aesthetics, Chinese opera often incorporates the philosophy of Yin and Yang in its themes and symbolism:

Harmony and Balance: Chinese opera seeks to achieve harmony and balance in its performances, just as the concept of Yin and Yang emphasizes the importance of maintaining balance in the universe. The interactions between the characters and the plot development often revolve around achieving harmony and resolving conflicts.

Transformation and Change: The constant interplay and transformation of Yin and Yang are mirrored in the dynamic and ever-changing nature of Chinese opera. Characters may undergo transformations in their roles and emotions, reflecting the fluidity and interconnectedness of Yin and Yang.

Cosmic Forces: Chinese opera often explores the influence of cosmic forces on human lives, drawing parallels with the concept of Yin and Yang shaping the destiny of individuals and societies.

Overall, the incorporation of Yin and Yang in Chinese opera adds depth and philosophical meaning to the performances, making it not only an art form but also a reflection of ancient Chinese worldview and cultural beliefs.

how is Chinese opera different from Western opera?

There are many differences between Chinese opera and Western opera. Here are some main distinctions:

Origin and development: Chinese opera originated from traditional performing arts and incorporates various art forms such as music, dance, drama, and poetry, resulting in a unique performance style and artistic value. On the other hand, Western opera emerged during the European Renaissance and is a product of musical art development, enriched with a diverse historical and cultural background.

Music and vocal style: Chinese opera’s music and vocal style typically employ ethnic scales and vocal techniques, aiming for sweet, bright, broad, and round sounds. In contrast, Western opera usually uses major and minor scales and emphasizes bel canto singing, seeking soft, clear, flexible, and expressive voices.

Plot and characters: Chinese opera often centers around historical or contemporary themes, emphasizing moral standards and values like loyalty, filial piety, friendship, and love. Western opera focuses more on emotional and psychological expression, frequently delving into themes of love, desire, and human nature.