Traditional Chinese textile holds a significant place in the rich cultural heritage of China. The country has a long and illustrious history of textile production, with techniques and designs that have been passed down through generations. From luxurious silks to intricate embroideries, traditional Chinese textiles showcase the exquisite craftsmanship and artistic sensibilities of the Chinese people. In this article, we will delve into the world of traditional Chinese textiles, exploring their history, techniques, and cultural significance.

What are the techniques of Chinese textiles?

Chinese textile refers to the wide range of fabrics, materials, and textile-related crafts that have been produced in China throughout its long history. Chinese textiles are known for their exquisite craftsmanship, intricate designs, and rich cultural significance. They encompass various techniques, including weaving, embroidery, printing, dyeing, and more.

Silk, one of China’s most famous contributions to the textile world, has played a central role in Chinese textile production for thousands of years. China is widely regarded as the birthplace of silk, and its production techniques were closely guarded secrets for centuries. Silk fabrics are known for their lustrous appearance, smooth texture, and lightweight feel. They have been used to create elegant garments, luxurious bedding, and exquisite decorative items.

In addition to silk, other natural fibers such as cotton, hemp, and wool have also been used in Chinese textile production. Each fiber has its unique qualities and is employed based on its suitability for different purposes. For instance, cotton is comfortable and breathable, making it suitable for everyday clothing, while wool provides warmth and insulation, making it ideal for winter garments.

Chinese textile techniques encompass a wide range of skills and craftsmanship. Embroidery is highly regarded in Chinese textile traditions, with different regions having their distinctive styles and motifs. Intricate embroidery is often used to decorate garments, accessories, and household items. Weaving techniques vary from region to region, resulting in a diverse range of textiles with different patterns, textures, and colors.

The designs and motifs found in Chinese textiles often carry cultural symbolism and meaning. These designs can feature mythical creatures like dragons and phoenixes, auspicious symbols, flowers, plants, and other elements that represent traditional beliefs, virtues, and wishes for prosperity, luck, and happiness.

what are Chinese textiles called?

Textile, Spinning, Fang zhi, Weaving, Printing and Dyeing, Printing Patterns, Woven Patterns.

The term “纺织” (textile) consists of two characters: “纺” (fāng) and “织” (zhī). The character “纺” depicts “糸” (mì), which represents silk thread, and “方” (fāng), which symbolizes a unified state. The combination of “糸” and “方” represents “silk thread that is collected and distributed by the state.” The character “织” (zhī) in traditional script consists of “糸” and “戠” (zhì). “戠” originally referred to military training formations and later came to represent patterns similar to group exercises. The combination of “糸” and “戠” represents “the inclusion of colored silk threads to create patterns during the process of weaving fabric.”

Ancient China had a long history of textile production and printing and dyeing techniques. In ancient times, textile production was referred to as “织造” (weaving). As early as primitive society, people adapted to climate changes by utilizing natural resources as raw materials for textile production and manufacturing simple hand tools for spinning and weaving. Clothing, airbags, curtains, and carpets in daily life are all products of textile production and printing and dyeing techniques.

traditional Chinese textile techniques

Traditional Chinese textile techniques encompass a wide range of skills and craftsmanship that have been developed and perfected over centuries. Here are some notable techniques:

Silk Production: Silk production is one of the most renowned textile techniques in China. It involves the cultivation of silkworms, the careful extraction of silk threads from their cocoons, and the spinning of these threads into yarn. This technique requires precision and delicacy to create the luxurious and lustrous silk fabric.

Embroidery: Chinese embroidery is a highly regarded textile technique known for its intricate designs and meticulous craftsmanship. It involves decorating fabrics with needle and thread, creating beautiful patterns, motifs, and images. Different regions in China have their distinct embroidery styles, such as Suzhou embroidery, Hunan embroidery, and Guizhou embroidery.

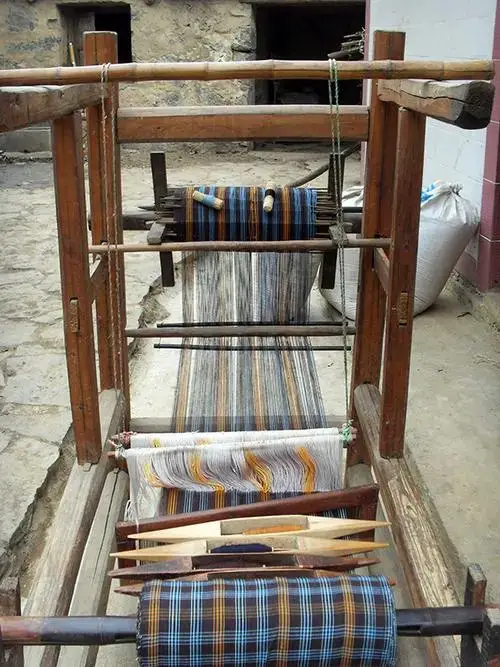

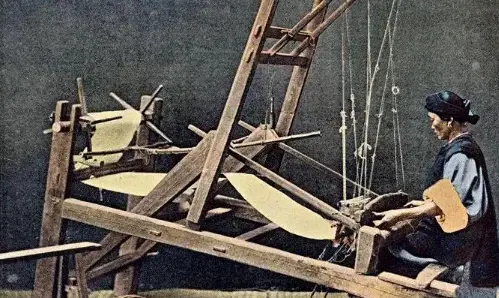

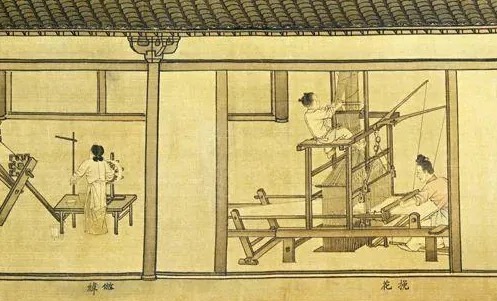

Weaving: Weaving techniques in Chinese textiles have a long history. Traditional looms are used to interlace warp and weft threads to create fabrics. Different types of looms are employed, including backstrap looms, horizontal frame looms, and foot-treadle looms. Weavers often incorporate various patterns, colors, and textures to produce unique textiles.

Batik: Batik is a traditional Chinese dyeing technique that involves applying wax-resistant patterns to fabric and then dyeing it. The wax prevents the dye from penetrating the areas covered, creating beautiful designs with contrasting colors. Batik techniques can be found in regions such as Guizhou and Yunnan, where ethnic minority communities have preserved this ancient art form.

Tie-Dye: Tie-dyeing is a technique where fabric is folded, twisted, or bound before dyeing, resulting in distinctive patterns. Chinese tie-dyeing, known as “zha ran,” is often seen in regions like Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangdong. It involves tying or binding sections of the fabric with threads or cords, creating areas of resist that result in unique and vibrant patterns.

Banana Cloth textile: Banana cloth is woven from the fibers of banana stems. According to records in “Taiping Yulan,” “Yiwu Zhi,” “Nanzhou Yiwu Zhi,” and “Guangzhi,” the traditional method of processing sugarcane stems involved boiling them in a cauldron to extract the fiber, which later evolved to using ashes for refining. This progression from boiling to ash refining reflects advancements in production technology. The ashes contain alkali, which, when mixed with water and soaked with banana stem bark, facilitates the removal of gum, resulting in purer banana fibers. The traditional weaving technique of producing banana cloth by the Zhuang ethnic group in Guangxi has long been praised. In the Western Jin Dynasty, Zuo Si’s “Wu Du Fu” praised banana cloth as even softer than typical summer cloth. During the Tang Dynasty, banana cloth was listed as a tribute. “Yuanhe Junxian Tuzhi” recorded the tribute of Hezhou and Binzhou banana cloth during the Kaiyuan period. From the Song Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, the production of banana cloth became more widespread and became an important material for clothing.

Bamboo Cloth textile: Bamboo cloth is a fabric woven by the Zhuang ethnic group using bamboo fibers. During the Tang Dynasty, bamboo cloth produced in Hezhou, Guangxi, was listed as a tribute. The Song Dynasty’s “Taiping Huan Yu Ji” records: “Bamboo cloth produced in Rongzhou.” Even in the Qing Dynasty, bamboo cloth was still produced in Guangxi. According to historical records, different types of bamboo such as single bamboo, ma bamboo, and jin bamboo were used. The process involved taking young bamboo, soaking it to remove gum, pounding it into fine fibers, and then weaving it.

Ge Cloth textile: Ge cloth is woven using fibers from the kudzu plant. Kudzu is a vine plant that grows both wild and cultivated. Kudzu fibers are longer and thinner than hemp fibers, resulting in finer and longer ge cloth. The production of ge cloth in the Zhuang ethnic region of Guangxi was prevalent as early as the Han Dynasty. In “Shiji – Huozhi Liezhuan,” the term “布” refers to ge cloth when it mentions “combining fruits and cloth.” Ge cloth is thin and cool, suitable for summer clothing. Due to the hot climate in the southern regions, ge textiles have remained popular. Guangxi has produced various types of ge cloth throughout its history, and the quality has been excellent. Some examples include Yulin ge cloth, Rongzhou jiao ge cloth, Binzhou ge cloth, and Xunzhou ge cloth. The “Xin Tangshu – Dili Zhi” records “Rongzhou tribute cloth” and “Yulinzhou tribute cloth,” indicating that ge cloth was offered to the imperial court during that time.

Hemp Cloth textile: Hemp cloth is one of the main textiles produced by the Zhuang ancestors. The finest “bai chan” and “lian zi” hemp cloths were woven by the Zhuang people in Yongzhou, Guangxi. According to “Lingwai Daida,” hemp cloth with delicate white and thin ramie fibers, adorned with patterns, is called “hua lian.” A piece of hua lian cloth could be over four zhang (approximately 12 meters) long and weigh only a few dozen qian (a unit of weight). It could be easily rolled into a small bamboo tube due to its lightweight and thinness. Hemp weaving was already well-developed during the Han Dynasty. In Luo Powan, Guixian County, the yarn count for cloth reached over 200S/1. Since the Tang and Song Dynasties, the Zhuang ethnic region of Guangxi has become an important production area for ramie cloth.

Gui Cloth textile: Gui cloth, also known as jibe, was produced in the Guiguan region during the Tang Dynasty, hence its name “Guiguan cloth.” The Guiguan cloth produced in Guangxi during the Tang Dynasty was pure white, thick, and warm, likely woven from fibers of grass, wood, and cotton. According to “Lingwai Daida – Jibe Tiao,” “jibe wood” is described as resembling small mulberry branches with hibiscus-like flowers, and its leaves are covered in fine fluff, with half-inch long cotton-like fibers. Removing the seeds from the fluff, people would spin the fibers by hand without the need for additional tools. This lightweight and soft cloth was highly regarded. The term “jibe wood” refers to cotton. From the Tang to the Song Dynasty, cotton cultivation was widespread in Guangxi. The cotton fabrics produced in the vicinity of the Xilu Lianzhou area varied greatly. Broad and fine-textured fabrics were called “man jibe,” while narrow and coarse fabrics with a darker color were known as “cu jibe.” There were also large cotton fabrics that were extremely wide and used for bedding and curtains.

Hemp Textile: Hemp textile production predates cotton textile production. Silk fabrics were worn by the nobility, while linen clothing was worn by the common people, characterized by its light color close to white. Thus, the common people were called “bai yi ren” (people in white clothes). Hemp cloth is considered cool, making it suitable for summer garments that help alleviate the heat. Additionally, hemp cloth is soft, breathable, resistant to sweat stains, and does not easily mold. Therefore, wearing hemp cloth during the hottest months helps cool the body. Due to its excellent breathability, hemp cloth is also used to make mosquito nets, providing a cool and refreshing environment. Hemp threads are used for fishing nets, and hemp cloth is used for net clothing in fishing operations. The hemp textile industry is attributed to Fuxi and Leizu, who are revered as ancestors of the craft. In some regions, the worship of Huang Daopo is also associated with hemp textile production.

Cotton Textile: The cotton textile industry in Jiangsu has a long history. It started in Taicang, Changshu, and Jiangyin and gradually expanded northward. Nantong became the center of cotton textile production within the province during the Qing Dynasty. The cotton fabrics produced there not only supplied the province but were also exported to northeastern regions and nearby provinces such as Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, and Henan. Cotton textile production in the Nantong area was decentralized, with thousands of households involved in self-production and self-sales. In the early 20th century, under the leadership of Zhang Jian, Nantong established large-scale textile factories utilizing machine spinning and weaving. Hand-woven fabrics were referred to as “tu bu” (local cloth), while machine-woven fabrics were called “yang bu” (foreign cloth). Huang Daopo, considered the founder of the cotton textile industry, was a famous figure. She was born in the Songjiang-Wunijing region during the Yuan Dynasty. Due to her family’s poverty, she became an adopted daughter-in-law, but unable to endure mistreatment from her in-laws, she fled to a commercial ship stranded in Wunijing. There, she learned textile techniques from the Li people and later taught the local people about cotton cultivation and the reformation of tools for cotton ginning, fluffing, spinning, and weaving. After Huang Daopo’s passing, the local people built temples in her honor. Soon, various temples were established in cotton-growing areas, including Huangpo Ci, Huang Gu An, Huangmu Ci, and Huang Daopo Chan Yuan. These temples housed statues of Huang Daopo, accompanied by two young girls, one holding a bunch of cotton yarn and the other holding a weaving shuttle. Every year during the Chongyang Festival, cotton weavers, especially female workers, would visit the Huang Daopo temple to burn incense and pray for a bountiful cotton harvest and prosperous textile industry.

types of Chinese textile

According to the processing materials:

Cotton Spinning: Refers to the processing of cotton fibers into yarn, which is used to produce cotton fabrics.

Silk Spinning: Refers to the processing of silk fibers into yarn, which is used to produce silk fabrics.

Flax Spinning: Refers to the processing of flax fibers into yarn, which is used to produce linen fabrics.

Wool Spinning: Refers to the processing of wool fibers into yarn, which is used to produce woolen fabrics.

Chemical Fiber: Refers to the processing of synthetic fibers, such as polyester, nylon, and acrylic, into yarn, which is used to produce various synthetic fabrics.

According to the weaving methods:

Warp Knitting: Refers to a method of knitting fabric where the yarns run in the lengthwise direction (warp direction) of the fabric.

Weft Knitting: Refers to a method of knitting fabric where the yarns run in the widthwise direction (weft direction) of the fabric.

Nonwoven: Refers to a method of fabric production where fibers or filaments are bonded together mechanically, chemically, or thermally, rather than being woven or knitted.

Common concepts:

Warp, Warp Yarn, Warp Density: Refers to the lengthwise direction of the fabric. The yarns running in this direction are called warp yarns, and the number of warp yarns per inch is called warp density.

Weft, Weft Yarn, Weft Density: Refers to the widthwise direction of the fabric. The yarns running in this direction are called weft yarns, and the number of weft yarns per inch is called weft density.

Density: Indicates the number of yarns per unit length of woven fabric, typically expressed as the number of yarns per inch or per 10 centimeters. In China, the national standard uses the number of yarns per 10 centimeters, but some textile companies still use the number of yarns per inch. For example, “45×45/108×58” indicates that the warp and weft yarns are both 45s, and the warp and weft densities are 108 and 58, respectively.

Width: Refers to the effective width of the fabric and is typically expressed in inches or centimeters. Common widths include 36 inches, 44 inches, and 56-60 inches, which are referred to as narrow, medium, and wide widths, respectively. Fabrics wider than 60 inches are considered extra-wide widths or wide-width fabrics. In China, extra-wide fabrics can reach a width of 360 centimeters. The width is usually indicated after the density, for example, the fabric mentioned in point 3 with a width of 60 inches would be represented as “45×45/108×58/60”.

Gram Weight: Refers to the weight of the fabric per square meter, typically expressed in grams. Gram weight is an important technical indicator for knitted fabrics and coarse woolen fabrics. Denim fabrics often use ounces to express the weight per square yard, such as 7-ounce or 12-ounce denim.

Yarn-dyed: Also known as “pre-dyed fabric” in Japan, it refers to a process where the yarn or filament is dyed before being woven into fabric. Fabrics produced using this method are called “yarn-dyed fabrics,” and factories specializing in producing these fabrics are called dyeing and weaving factories. Examples include denim fabric and most shirt fabrics.

Classification of Textile Products

I. Classification by Different Processing Methods:

Woven Fabrics: Fabrics formed by the interlacing of yarns arranged in both the horizontal (weft) and vertical (warp) directions on a loom. Examples include denim, jacquard satin, flannel, and linen fabrics. There are various methods to classify woven fabrics.

(a) Based on the types of fibers used, they can be categorized as pure fabrics, blended fabrics, or mixed fabrics.

- Pure fabrics: Made from yarns of the same fiber type. For example, pure cotton fabrics consist of cotton yarns (e.g., 21×21/108×58), and viscose fabrics consist of viscose yarns.

- Blended fabrics: Made from yarns composed of two or more different types of fibers. Examples include cotton-linen blends, polyester-cotton blends, and polyester-wool blends. The fibers are blended together during the spinning process, typically in the opening and blending stage.

- Mixed fabrics: Consist of yarns or filaments of different fibers in the warp and weft directions. For instance, a fabric may use nylon filament in the warp and viscose yarn in the weft.

- (b) Based on the length and fineness of the fibers used, fabrics can be classified as cotton-type, medium-long, wool-type, or filament-type fabrics.

- Cotton-type fabrics: Made from cotton fibers with a length of approximately 30 millimeters. The yarns used to produce these fabrics are called cotton-type yarns. Examples include fabrics labeled as pure cotton.

- Wool-type fabrics: Made from wool fibers with a length of around 75 millimeters. The yarns used to produce these fabrics are called wool-type yarns.

- Medium-long fabrics: Made from fibers with lengths between cotton-type and wool-type fibers. The yarns used to produce these fabrics are called medium-long yarns.

- Filament-type fabrics: Made from long filaments, such as synthetic fibers. Examples include fabrics made from rayon or polyester.

- (c) Fabrics can also be classified based on their weave structures, such as plain weave, twill weave, satin weave, and other weave structures. The concept of weave structures has been mentioned earlier.

- (d) Fabrics can be classified based on their intended uses, such as clothing, home textiles, or industrial fabrics.

Knitted Fabrics: Fabrics formed by the interlooping of yarns into a series of rows or courses. They can be classified as weft knits or warp knits.

(a) Weft Knits: Yarns are fed into the knitting machine in the weft direction, forming sequential loops.

(b) Warp Knits: Yarns are fed into all the needles of the knitting machine in the warp direction simultaneously, resulting in loop formation. There are two main categories of warp knits: tricot knits and raschel knits.

Nonwoven Fabrics: Fabrics made by bonding or interlocking loose fibers without weaving or knitting. The main methods used are bonding and needling. Nonwoven fabrics offer simplified production processes, cost-effectiveness, and increased productivity, making them highly promising for various applications.

II. Classification by the Composition of Yarn Materials:

Pure Fabrics: Fabrics made from a single type of fiber, such as cotton fabrics, wool fabrics, silk fabrics, and polyester fabrics.

Blended Fabrics: Fabrics made from yarns consisting of two or more different fiber types blended together. Examples include polyester-viscose blends, polyester-acrylic blends, and polyester-cotton blends.

Mixed Fabrics: Fabrics made from yarns formed by combining two different fibers, typically with one as the core and the other as the sheath. Examples include fabrics with a core of low-stretch polyester filament and a sheath of acrylic or fabrics with a core of polyester staple fiber and a sheath of low-stretch polyester filament.

Interwoven Fabrics: Fabrics created by using different fibers in the warp and weft directions. Examples include fabrics with silk warp and synthetic weft.

III. Classification by Whether the Constituent Yarns are Dyed:

Grey Fabrics: Fabrics made from unbleached or undyed yarns and processed into finished fabrics. They are also referred to as “grey goods” in silk weaving.

Dyed Fabrics: Fabrics made from bleached or dyed yarns or fancy yarns and processed into finished fabrics. In silk weaving, they are referred to as “dyed goods.”

IV. Classification of Novel Fabrics:

Bonded Fabrics: Fabrics formed by bonding two pieces of fabric back-to-back. The bonded fabrics can include woven fabrics, knitted fabrics, nonwoven fabrics, or vinyl films, and various combinations of these materials.

Flocked Fabrics: Fabrics covered with short and dense fiber pile, giving them a velvet-like appearance. They can be used as clothing fabrics or decorative materials.

Foam Laminated Fabrics: Fabrics with foam plastic adhered to the base fabric, often used in cold-weather clothing.

Coated Fabrics: Fabrics coated with materials such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or chloroprene rubber, providing excellent waterproofing properties.

Main Chinese Textiles

Chinese textile, with a long history, can be categorized into four major types: embroidery, silk, clothing, and carpets. These four types have distinct production techniques and unique styles. Below is a brief introduction to each of them.

Embroidery:

Embroidery is a form of handcraft that developed based on general sewing techniques, signifying a significant advancement in human civilization. Chinese embroidery has a long history, dating back to the Neolithic period. The Hemudu culture, which existed over 7,000 years ago, already employed bone needles and engaged in textile production. Chinese embroidery has generally evolved along the following lines: starting with embroidered garments, expanding to embroidered daily necessities, and later progressing to embroidered artworks. It can be divided into two categories: embroidered daily-use items and embroidered paintings.

Embroidery is an original art form created to enhance the beauty of life. It is characterized by its simplicity and innocence, expressing the inner sentiments of the embroidery artists.

Silk:

Silk is a liquid excreted by silkworms during the cocooning process. It solidifies through air coagulation, composed of silk protein and sericin. Silk exhibits excellent properties, such as high tensile strength and elasticity. A single silkworm can produce approximately 1,000 meters of silk thread. Sericulture, reeling silk from cocoons, and silk weaving and embroidery were the main labor activities of ancient Chinese women. The impact of this tiny creature on Chinese life and its global resonance are remarkable.

When did silk fabrics first appear in China? According to archaeological evidence, silk fabrics in China originated from the Liangzhu culture in the southeastern region during the Neolithic period, dating approximately between 2735 and 2175 BC.

The Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) and the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) were two flourishing periods of silk production. Silk weaving reached its peak during these periods, leaving behind numerous artifacts. China has long been not only the country that invented silk but also the sole country with this handicraft industry. Due to the export of high-quality silk textiles, China has been hailed as the “Silk Country” by countries around the world.

The term “chou” refers to a category of silk fabrics. Chou has a fine and dense texture, not excessively thin, and can be categorized as raw silk, processed silk, and plain weave (with simple patterns on the surface).

The patterns and motifs on Chinese silk fabrics have exhibited a rich and diverse landscape from the beginning. Regardless of small or large flowers, single-color or multicolor designs, or geometric or natural forms, they adapt to the structure and practical use of silk textiles while harmonizing with contemporary artistic decorations. Traditional Chinese decorative patterns emphasize not only the aesthetic appeal but also the auspicious meanings. The themes of averting evil and bringing good fortune aim to ensure peace and blessings.

Silk brocade and satin have won the love of all humanity with their magnificent and noble qualities. Various weaving techniques and distinct artistic craftsmanship have made them intricate and diverse, contributing to their three thousand years of glory.

Chinese minority nationality textile

Batik

Ethnic minorities in border areas have also made significant developments in textile and dyeing techniques. Examples include the carpets, tapestries, Hui brocade, and silk from Hotan created by ethnic minorities in Northwest China, as well as Miao brocade, Dong brocade, Zhuang brocade, and Tujia batik from ethnic minorities in Southwest China. These textiles possess rich local flavors and distinct ethnic aesthetic characteristics, representing their vibrant cultural heritage.

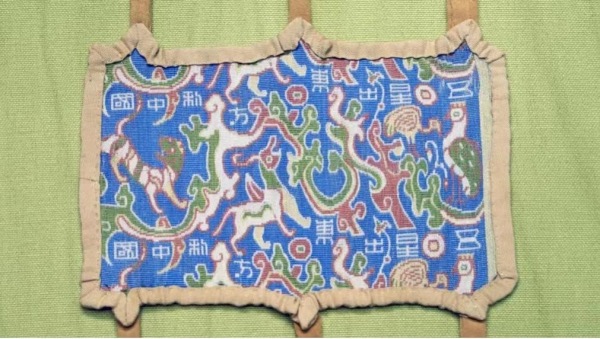

Batik is an ancient traditional textile dyeing and printing craft practiced by ethnic minorities in China. With a piece of square cloth and a foot of blue fabric, they create intricate patterns stroke by stroke. It resembles cascading waterfalls or white smoke on snow. The combination of blue background and white patterns achieves a simple yet exquisite beauty. Batik was particularly popular during the Tang Dynasty, and its techniques became increasingly refined. It can be categorized into two types: single-color dyeing and multicolor dyeing. However, batik began to decline since the Song Dynasty, yet it has been passed down as an ancient traditional textile dyeing and printing craft among China’s ethnic minorities. In 2006, Miao batik techniques were listed as a national-level intangible cultural heritage.

Zhuang Ethnic Textiles

Zhuang brocade is a renowned textile craft among the Zhuang ethnic group. It is woven using cotton yarn and five-color silk velvet, featuring unique patterns and high durability. The production of Zhuang brocade has been recorded since the Tang and Song Dynasties over a thousand years ago.

During the Qing Dynasty, Zhuang brocade production spread throughout the Zhuang ethnic areas and became popular as clothing and a highly demanded product in the market. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Zhuang brocade saw new developments, with continuous innovation in pattern designs and expanding applications such as wall hangings, tablecloths, seat cushions, sofa covers, curtains, and more. Nowadays, Zhuang brocade produced in Jingxi and Binyang in Guangxi is well-received both domestically and internationally.

Li Ethnic Textiles

Li brocade, also known as Li silk, is one of the ancient traditional textile crafts among the Li ethnic group, making it a “living fossil” in the history of Chinese textiles with a history of over 3,000 years.

Li brocade is mainly woven using materials such as island cotton, ramie, kapok, hemp, bark fibers, and silk. The four major techniques involved in traditional Li brocade production—spinning, weaving, dyeing, and embroidery—are the fundamental basis for the formation of Li traditional costumes and an ancient craft created by the Li ancestors.

The exquisite techniques of Li brocade, such as yarn twisting, color matching, multiple warp threads, and pattern weaving, are all products of Li women’s ingenuity. Li girls start learning spinning and embroidery from the age of six or seven, growing up with the influence of traditional textile techniques. They use primitive waist looms and weave fabrics while sitting, creating plain weaves and intricate patterns, meticulously embroidering their craftsmanship into artistic textile pieces. The flower cloths, sashes, quilts, tube skirts, and wall hangings woven by them were vividly described by Tao Zongyi in his book “Nancun Chuogeng Lu” (Record of Idle Farming in the South Village). Li residents from different regions continuously create new spinning, weaving, dyeing, and embroidery techniques based on their preferences.

The cultural significance of Li brocade patterns is highly distinctive and reflects the rich cultural heritage of the Li ethnic group. According to experts’ research, there are over 140 patterns in Li brocade, some even claim over 160 patterns. These patterns are not representational but composed of dots and lines, often appearing in geometric forms, characterized by abstraction, generalization, and simplification. They are the crystallization of the Li people’s culture spanning thousands of years. The patterns in Li brocade can be broadly categorized into human figures, animal motifs, plant motifs, landscapes, as well as patterns representing daily tools, natural phenomena, and Chinese characters. Human figures, animal motifs, and plant motifs are the most common, particularly seen in tube skirts, double-sided embroidery, and dragon robes within Li brocade. These pattern designs contain rich cultural connotations, reflecting the Li people’s perspectives on nature, history, society, aesthetics, and values.

As the Li ethnic group possesses language but not a written script, researchers often study the social history, ideological consciousness, religious beliefs, customs, ethnic ethos, and cultural characteristics of the Li ethnic group through these patterns. Therefore, Li brocade is praised as the “living history worn on the body,” the “encyclopedia of the Li ethnic group,” and the “epic of the Li ethnic group.” It plays an irreplaceable role in enriching and developing Chinese culture.

With the development and progress of social and cultural life, Li brocade has gained increasing attention. In October 2009, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) officially approved Hainan Province’s “Li Ethnic Traditional Textile Dyeing, Weaving, and Embroidery Techniques” to be included in the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Urgent Need of Safeguarding.

Miao Ethnic Textiles

Miao brocade, known as Miao embroidery, is a traditional jacquard fabric woven by the Miao ethnic people. It is divided into plain brocade and colored brocade. Plain brocade features only black and white, also known as high mountain Miao brocade, while colored brocade displays vibrant colors and diverse variations. Another example is Dong brocade, a type of brocade produced by the Dong ethnic group. It is documented in the Qing Dynasty’s “Qiandongnan Prefecture Annals” (Liping Prefecture Annals) as “cotton brocade” and is often black and white or colored. It has a plain weave ground structure with raised weft patterns, mostly appearing as geometric patterns, flora, and fauna. Zhuang brocade, a traditional fabric of the Zhuang ethnic group, utilizes fibers such as hemp, cotton, and silk. The weave structure is a plain weave with supplementary weft patterns, showcasing patterns of birds, animals, and flowers within a geometric framework, characterized by strong color contrasts and vivid hues. It is used for short jacket trims, brocade skirts, belts, headscarves, backpacks, and quilts (replica specimens are available in the exhibition hall).

Bulang Ethnic Textiles

The Bulang ethnic group excels in traditional textile techniques and has enjoyed a prestigious reputation in history. Bulang people primarily create their own clothing from homemade coarse cloth, mainly in blue and black colors. They utilize self-grown cotton, ramie, and kenaf fibers as raw materials. Cotton and ramie can be spun into coarse cloth, while kenaf and ramie fibers are used for sewing sacks or purses. The Bulang ethnic group’s textile techniques have an early origin. Ancient Chinese texts from thousands of years ago mention the Bulang people spinning cloth from kapok. “Guangzhi” states, “Kapok is produced by the Bulang people, and there is kapok in the soil.” “Hei Boluo” (black Bulang) is mentioned in “Qianji” (Liping Prefecture Annals), which refers to cotton brocade. The colors used in Bulang brocade are mostly black, and there are also blue and white variations, along with some colored pieces. The ground structure is a plain weave with a float weft, displaying patterns of geometric flowers, animals, and birds. The color contrast is strong, creating vivid tones. Bulang brocade is used for short jacket trims, brocade skirts, belts, headscarves, backpacks, and quilts (replica specimens are available in the exhibition hall).

The Bulang ethnic group does not have a written script but a spoken language. Many unique customs and cultures can only be passed down through oral traditions. Therefore, the traditional textile techniques of the Bulang ethnic group face significant challenges. Currently, only the Bulang villagers of Bangbing, Nan Zhi, and Nan Xie in Shuangjiang still possess the knowledge and skills to create “bull belly quilts.” The inheritance and protection of this craft are not optimistic.

Yi Ethnic Textiles

The Yi ethnic group has a long history and is the largest minority group in Yunnan. They are not only populous but also scattered throughout the province, with significant populations in Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, and Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture. The Yi ethnic group has numerous branches, with an estimated number exceeding 30. Each branch lives in close proximity to other ethnic groups, resulting in significant mutual influences in various aspects, including politics, economy, culture, lifestyle, customs, and also textile techniques. The Yi ethnic group’s textile techniques primarily consist of three types: hemp textile techniques, cotton textile techniques, and wool textile techniques. Hemp textile techniques are widely used in the central Yunnan region where the Yi people are predominantly settled, while cotton textile techniques are primarily used in the Red River and adjacent areas. Wool textile techniques are mainly employed in northeastern and northwestern Yunnan, where the climate is cold.

Hemp Textile Techniques

Due to the diverse economic development levels among Yi ethnic branches, variations exist in hemp textile techniques. Here, we will focus on the representative hemp textile techniques of the Sani branch of the Yi ethnic group, primarily living near Kunming in Shilin County. Although agriculture is their main occupation today, hemp textile production remains one of the significant activities for Sani women. The month of May in the lunar calendar is the time when women plant hemp. With the assistance of men in their households, they sow hemp seeds in “hemp ponds.” After approximately one month, when the hemp plants reach around 20 centimeters in height, they require weeding and thinning. To obtain more stem fiber, the density of the hemp plants is relatively high.

In early October, the hemp plants have matured, and the women use sickles to cut them down, bind them into small bundles, and bring them home to dry. From the harvesting day until April of the following year, it is the retting period. Particularly in March and April when the temperature is higher, it is the most suitable time for retting, which takes about two days and two nights. The most common method is pond retting, where the hemp plants are spread out and placed in the water, pressed down with stones or wooden hooks attached to crossbars, ensuring that the plants are immersed in water. After retting, the hemp fibers are easily separated from the stalks and can be easily torn off.

After the autumn harvest, almost all women take advantage of the evenings to peel the hemp, breaking the stalks and tearing off the stem bark into small strips about 1 millimeter wide. Then, they use the wrapping and joining method to connect them piece by piece. The Sani people use a larger hemp spinning wheel for spinning. The spinning wheel is a horizontal type, with a frame width of 170 centimeters and a rope wheel diameter of 85 centimeters. The spinning wheel leans against the wall at an angle of approximately 70 degrees. During spinning, the person stands, operating the wheel with the right hand and feeding the hemp fibers with the left hand. After spinning the yarn, they use a self-made winding frame, which can be as long as 200 centimeters, to wind the yarn.

After winding the yarn, the second degumming process is carried out. The degummed yarn is repeatedly rinsed in water or boiled in ash water before rinsing. The yarn, after rinsing, becomes white and soft, resulting in a white, soft, and warm hemp cloth when woven. In recent years, after the Sani women wash the hemp yarn, they also soak it in egg white. It is said that this makes the yarn smoother, easier to weave, and the resulting hemp fabric more even. Before weaving, the Sani people also perform warping. Warping is done using the “five-stake method.” The Sani weaving looms are mostly set up on the side of the main hall. When viewed from the front, the loom has a “U” shape, about 200 centimeters high and 60 centimeters wide, with two long poles for holding the warp threads and the shuttle box. The weaver stands in front of the loom, slightly leaning forward, using their feet to treadle, opening the shed for the warp threads, passing the weft with the shuttle, and pressing the shuttle box tightly to complete one weaving process.

Wool Textile Techniques

Yi ethnic groups in northeastern and northwestern Yunnan, where livestock rearing is more common, excel in wool textile techniques, primarily using sheep’s wool. In the past, the wool fibers were collected through shearing, but due to limited livestock, shearing was often done when they needed meat. In areas with more livestock, live shearing is practiced. During the warm weather of March and April, the women use scissors to shear the wool, remove bloodstains and impurities, air and fluff the wool, and then it can be spun. The Yi people’s wool spinning does not generally use spinning wheels but rather employs hand spinning or spinning wheels. However, using only hands to twist the fibers together results in low efficiency and slow speed. The use of spinning wheels significantly increases the speed. The spinning wheel is of the flyer type, with a larger diameter, sturdy texture, and heavier weight. Nevertheless, the spinning wheel’s rotation speed is still not fast enough.

Later on, people started using two narrow wooden boards to aid in spinning and increase the rotation speed of the spinning wheel. After spinning the wool, the warp process follows. The width of Yi ethnic group’s woolen fabrics is not wide, and the yarn is relatively coarse, so the warping process is not complex. They only need to tie the warp threads to wooden stakes, with two people holding each end and moving back and forth, forming a “Z” shape. After the warping process, they can move on to weaving.

Weaving is done on a traditional foot-treadle loom, utilizing the lever principle of physics. The shed control is achieved by operating the foot pedals, raising and lowering the heddles to separate the warp threads into upper and lower layers, forming a triangular-shaped shed. The weft is driven by the shuttle, passing through the intersecting layers of warp threads from left to right. Treading the foot pedal adjusts the shed, alternating the positions of the warp threads, clamping the weft, and pressing it tightly with the heddles. The weft then passes from right to left through the warp threads, and this process continues in a repetitive cycle to produce woolen fabric.

Buyi Ethnic Textiles

The Buyi ethnic group traditionally chooses hand-woven cotton fabric for their dyed and embroidered textiles. The process of cotton fabric production involves several stages, including cotton fluffing, rolling cotton strips, spinning yarn, winding yarn, boiling yarn, winding thread onto bobbins, carding, and warping.

Weaving alone involves the following steps:

Tying the Warp Threads:

The prepared yarn bobbins are threaded through bamboo skewers and placed on the warp stand. The loose ends of the threads are passed through the holes in the wooden frame. The ten thread ends are tied together at a corner of a table to start the tying process. The person tying the threads needs to have rich experience and must be careful and patient as any slight mistake can undo previous efforts. These threads being tied are the warp threads that will be installed on the loom, and the number of warp threads determines the width of the cotton fabric.

Due to the different specifications of the loom’s reed, the number of thread bobbins and the number of turns for winding need to be precisely calculated based on the reed’s specifications. When additional thread bobbins need to be added (when the available thread bobbins are insufficient, new ones need to be made to supplement them), the person uses their left hand to hold the threads while their right hand turns the handle, and the rope wheel rotates, winding the starched cotton threads into bobbins. After a few minutes, the winding of the bobbins is completed, which are used to supplement the thread stand. Tying the threads often requires cooperation among multiple people. Finally, palm leaves are used to tie the intersecting positions of the warp threads. This unique method of securing the threads prevents them from getting tangled, facilitating subsequent processing. Once the tying process is complete, the next step is to proceed with the thread joining.

Thread Joining and Thread Pulling:

Thread joining and pulling have a unique knotting method that neither consumes the original warp threads nor weakens the strength of the knot. Once the warp threads are successfully joined, the thread joining process is completed, and the next step is thread pulling.

To pull the threads, one end of the warp beam (the beam containing the warp threads) is tied to a tree stump, and wooden sticks are used to separate the threads at the intersections. The other end needs to be pulled taut by someone, separating each individual warp thread by hand.

After carefully separating the warp threads, the warp beam and reed are moved to a new set of white cotton threads. Then, carding is carried out. Once carding is completed, the warp beam is installed on the loom’s frame, pulled taut with the weight shifted to the rear, and two people work together to continuously wind the warp threads onto the beam, gradually approaching the warp beam. The warp threads are carefully gathered, and then the process of setting up the loom for weaving begins.

Loom Weaving:

The traditional foot-treadle loom utilizes the lever principle from physics. The foot pedals control the up and down movement of the warp beam, separating the warp threads into upper and lower layers, forming a triangular-shaped shed. The shuttle, driven by the foot-treading motion, carries the weft yarn from left to right, passing through the intersecting layers of the warp threads. The foot-treading action controls the shedding motion, changing the positions of the warp threads to catch the weft yarn. The heddles are pressed tightly against the warp threads using force from the right hand. Then, the weft yarn passes from right to left through the warp threads. This process repeats, allowing the weaving of cotton fabric.

what are Chinese textiles made of?

Ancient Chinese textile had a rich variety and exquisite craftsmanship, containing a wealth of historical information that reflects the development of politics, economy, culture, and technology. According to archaeological evidence, ancient Chinese textiles were primarily made from four main types of materials: cotton, flax, silk, and wool.

Cotton:

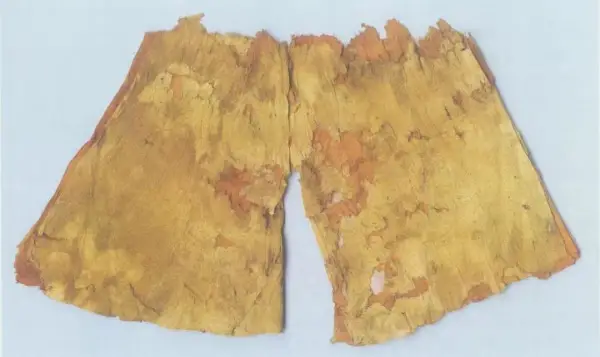

Cotton fiber, known as “mian” in Chinese, is obtained from the seeds of cotton plants. The fibers are separated from the seeds to produce raw cotton or lint. Depending on the thickness, length, and strength of the fibers, raw cotton can be classified into long-staple cotton, fine-staple cotton, and coarse-staple cotton. Cotton cultivation and utilization can be traced back to the Qin and Han dynasties in the southern and southwestern regions of China, as well as Xinjiang. The use of cotton fabric became widespread during the Song and Yuan dynasties and eventually became the primary material for clothing. Archaeological findings have unearthed cotton fabric remnants dating back 3,200 years in Fujian, cotton garments in Astana Tombs dating back to the Tang Dynasty, and blue and white printed cotton fabric from the Northern Dynasties in Xinjiang.

Flax:

Flax, including ramie and linen, was one of the earliest textile materials used by the Chinese people. Flax weaving techniques have a history of over 6,000 years in China. Archaeological discoveries at Hemudu and Qianshan Yangshao Neolithic sites in Zhejiang have revealed remnants of flax fabrics and ropes. In 1981, linen and hemp fabric patterns adhering to red pottery were found at the Qingtai archaeological site in Zhengzhou, dating back approximately 5,500 years. Other archaeological findings include flax fabrics from the Wu Yi Mountain Rock Tomb in Fujian dating back to around 1400 BC and flax and hemp textiles from the Xianyan tomb in Guixi, Jiangxi, dating back to the early Warring States period. Flax was used for clothing during the Zhou Dynasty and served as a protective layer over silk garments. However, due to its rough texture, flax gradually became primarily used for making ropes as cotton fabric gained popularity from the Qin Dynasty onwards.

Wool:

Ancient Chinese textile also utilized various animal fibers, including sheep’s wool, goat’s cashmere, yak’s hair, rabbit fur, and feathers. Handmade woolen textile production can be traced back to the New Stone Age in regions such as Xinjiang, Shaanxi, and Gansu. Wool fabrics and blankets dating back to approximately the 19th century BC were discovered in the Lop Nur region of Xinjiang. In the late autumn of 1978, exquisite woolen fabrics with twill and plain weave structures were unearthed at the Wubao Cemetery in Hami, dating back to around 1200 BC. Numerous ancient wool textiles have also been found at the Nuo Mu Hong site in southern Qinghai.

Silk:

Silk fiber, derived from silkmoth cocoons, has a long history in China and is a renowned ancient Chinese specialty. Silk weaving originated in China, and the discovery of silk textiles dates back to the Neolithic period. In 1958, silk fabrics dating back over 2,700 years were found at the Qianshan Yangshao site in Zhejiang, making them the earliest known silk textiles in China. The excavation at the Niya archaeological site in Xinjiang in 1995 revealed a Han Dynasty silk brocade armguard with inscriptions in seal script that read, “Five stars rise in the east to benefit China.” During the Western Zhou Dynasty, a technique called “jingjin” emerged, which involved using multiple colored silk threads to create elaborate patterns. By the Warring States period, silk textile designs had evolved from geometric patterns to animal motifs, with an increase in color richness. Chinese silk fabrics were highly sought after and exported to Central Asia, West Asia, Africa, and Europe through the Silk Road during the Han and Tang dynasties. The silk industry reached a stable development period, and new techniques and artistic designs emerged, including weaving, printing, embroidery, hand-painting, and gold weaving.

Chinese fabric types

In ancient Chinese textile, there were various types of fabrics, including brocade, damask, silk, satin, linen, and coarse cloth.

Brocade: Silk fabric woven with complex patterns and multiple colors, known for its vibrant and intricate designs. Brocade is a famous type of silk fabric, and it is highly valued for its artistry. There are different types of brocade, such as Shu Brocade, Song Brocade, and Yun Brocade.

Damask: Silk fabric with a subtle pattern woven in a twill weave or with varying patterns. It has a lightweight texture with diagonal designs on the fabric surface. Damask fabrics were known for their resemblance to ice formations and were highly regarded.

Silk: Silk fabrics made from silk fibers or silk blended with other fibers. They are woven using a plain weave or variations, resulting in tightly woven fabrics with a smooth and glossy surface. Silk is a general term for silk textiles, known for their firmness, fineness, and smooth touch.

Satin: Fine fabric made from a blend of silk and flax fibers. Satin is woven in a satin weave or variations, creating a smooth, lustrous, and dense silk fabric.

Linen: Fabric made from various plant fibers, such as flax, ramie, jute, hemp, or banana fibers. Linen fabrics are breathable, comfortable, durable, resistant to washing and sunlight, and possess natural antimicrobial properties.

Coarse cloth: Cotton fabric also known as “tubu” or “tuchu.” It has a long history in China, where laborers carefully weave cotton threads on primitive spinning wheels and wooden looms. Coarse cloth is characterized by its simplicity and is made from pure cotton. It has been used for thousands of years in China.

what are Chinese textiles used for?

Chinese textiles have been used for a wide range of purposes throughout history. Here are some of the main uses of Chinese textiles:

Clothing: Textiles have been primarily used for clothing in China. Fabrics such as silk, cotton, linen, and wool have been woven into various garments, including robes, dresses, shirts, pants, and accessories. Different types of textiles were used depending on factors such as climate, social status, occasion, and personal preference.

Home Furnishings: Chinese textiles were extensively used for home furnishings. Silk brocades, damasks, and tapestries were used for decorative purposes, including wall hangings, window curtains, and furniture coverings. Additionally, textiles were used for bedding, cushions, tablecloths, and other household items.

Accessories and Adornments: Chinese textiles were utilized for creating accessories and adornments. Silk and embroidered fabrics were used for making handbags, purses, belts, hats, shoes, and other fashion accessories. Intricate embroidery and weaving techniques were employed to create decorative patterns and motifs.

Ritual and Ceremonial Use: Textiles played a significant role in religious and ceremonial practices in ancient China. Elaborate silk textiles were used for making ritual garments, ceremonial robes, and temple decorations. These textiles often featured intricate embroidery, luxurious patterns, and symbolic motifs.

Trade and Export: Chinese textiles, especially silk, have been highly sought after and traded internationally for centuries. The Silk Road facilitated the exchange of Chinese textiles with other cultures, contributing to cultural exchange and economic prosperity. Chinese silk textiles were exported to various regions, including Central Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Southeast Asia.

Art and Craft: Textiles were used as a medium for artistic expression and craftsmanship in China. Skilled artisans created exquisite embroidered artworks, tapestries, and woven fabrics with intricate patterns, scenes, and calligraphy. Textile art forms, such as silk embroidery and brocade weaving, were valued as expressions of Chinese aesthetic traditions.

Symbolism and Significance: Chinese textiles often held symbolic meanings and cultural significance. Certain patterns, motifs, and colors were associated with specific themes, virtues, or auspicious symbols. Textiles were used to convey social status, demonstrate cultural identity, and express artistic and cultural values.

Overall, Chinese textiles were utilized in various aspects of daily life, reflecting the rich cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and artistic traditions of China.

Chinese textiles history

China is one of the earliest producers of textiles in the world. As early as the primitive society, people collected wild materials such as kudzu, hemp, and silkworm silk. They used feathers and fur from captured birds and animals to create crude clothing, replacing grass leaves and animal skins as body coverings. In the later period of the primitive society, with the development of agriculture and animal husbandry, people gradually learned methods of cultivating and processing textile materials, such as growing flax for fiber, shearing wool from sheep, and extracting silk from silkworms, and they also utilized various tools. Some tools were composed of multiple parts, while others had multiple uses, greatly improving labor productivity. At that time, textiles already featured patterns and were dyed with colors. However, all the tools were directly operated by hand, thus referred to as primitive handcrafted textiles.

From the Xia Dynasty to the Spring and Autumn Period, textile production experienced significant developments in both quantity and quality. The quality of raw materials improved, and textile combination tools evolved into primitive spinning wheels, spinning machines, and looms through long-term improvements. Labor productivity greatly increased. Some textile producers gradually specialized in their craft, leading to increasingly refined spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing techniques. Textile products became abundant for trade and sometimes even served as a medium of exchange, functioning as currency. Product specifications gradually transitioned from crude to meticulous standards. During the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, silk weaving technology particularly developed. By the Spring and Autumn Period, silk fabrics had become highly exquisite. The diverse weaving patterns, coupled with rich colors, made silk fabrics renowned as noble clothing both domestically and internationally. This stage marked the emergence and formation of handcrafted machine textiles.

From the Qin and Han Dynasties to the late Qing Dynasty, silk remained a renowned Chinese specialty. The major textile raw materials underwent several changes: from kudzu gradually being replaced by hemp during the Han to Tang Dynasties, and from hemp being replaced by cotton during the Song to Ming Dynasties. During this period, handcrafted textile machinery continuously developed and improved. Various forms emerged: spinning machines and spinning wheels progressed from manual single-spindle operation to multi-spindle operation (with 3-5 spindles) and foot-operated mechanisms; looms appeared in both plain and patterned designs. Patterned looms further developed into multi-harness, multi-pedal looms, and warp-weighted looms (where individual warp threads are raised and lowered). Since the Song Dynasty, multi-spindle spinning wheels suitable for collective workshop production emerged. In some regions, “water-powered spinning wheels” utilizing natural power sources also appeared. The techniques of spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing gradually matured. Textile fabrics featured a wide variety of patterns, with known primary fabric weaves (plain weave, twill weave, and satin weave) all appearing during the Song Dynasty. Silk fabrics not only maintained their status as high-quality products but also continuously produced craft-based textiles for appreciation. During the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, cotton textile technology rapidly developed, leading to the gradual replacement of hemp fabrics with cotton fabrics in everyday attire. This stage represents the development of handcrafted machine textiles.

In the second half of the 18th century, Western Europe developed powered textile machinery based on handcrafted textiles, gradually establishing a system of collective large-scale production in textile factories, which later spread to other industries, significantly improving social productivity. Western European countries extensively exported machine-produced “cotton yarn” and “cotton cloth” to China, severely impacting China’s handcrafted textile industry. After China’s defeat in the Opium War, the country began to introduce European textile technology from 1870, establishing modern large-scale textile factories. This led to a long-term coexistence of concentrated textile production in a few major cities and decentralized handcrafted machine textile production in rural areas. However, the development of industrialized textile production was slow, and by 1949, the dominant cotton textile production scale was still only around 5 million spindles. This marked the stage of the formation of large-scale industrialized textiles.

After 1949, textile production rapidly developed in China. The scale of cotton textile production expanded quickly, and there was corresponding development in wool, hemp, and silk textile production. Textile technology also improved, allowing for the manufacturing of complete sets of textile dyeing and finishing machinery and equipment. Chemical fiber production also developed rapidly. However, in terms of per capita capacity, particularly in the case of cotton textile production, it was still less than half the world average and far below that of industrially developed countries.

Origins and Evolution of Chinese Textiles

After entering the fishing and hunting society, humans learned to twist ropes, which served as a prelude to spinning. The Xujia Village Site in Datong, Shanxi, dating back 100,000 years, unearthed over 1,000 stone balls. A slingshot, made of a net made from ropes, was used to throw stone balls at wild animals during hunting. This suggests that people at that time had already learned to use ropes. Initially, ropes were made from whole plant stems. Later, the technique of splitting stems was discovered. The plant stems were split into thin strips (also known as flax), which were then twisted together (or assembled) to create long ropes using the friction between the individual strands after twisting. To increase the strength of the ropes, people also learned to combine several strands. Ropes unearthed from the Hemudu Site in Zhejiang, dating back to 4,900 BC, were composed of two strands. The fiber bundles were split, and single strands were twisted in an S direction, while the combined strands were twisted in a Z direction, resulting in a diameter of up to 1 centimeter.

To keep warm, early humans initially used grass leaves and animal skins as coverings. This led to the development of techniques such as braiding, cutting, and stitching. Stitching grass leaves required the use of ropes, while stitching animal skins initially involved drilling holes with awls and threading them with fine strings. The discovery of stone awls has been found among artifacts from the Zhoukoudian Old Stone Age site in Beijing, while bone needles dating back to around 16,000 years ago have been found among the remains of the Shanidar Cave people. Bone needles were precursors to weaving instruments and were the most primitive weaving tools. With the use of bone needles, ancient Chinese began to make sewing thread. Based on the experience of twisting ropes, people invented the techniques of spinning and weaving. “Ji” referred to the technique of splitting plant stem skins into extremely fine, long fibers, which were then individually joined. This was a highly skilled craft, so the term “achievement” (“cheng ji”) was later used to refer to one’s work. Animal fur and silk fibers themselves were already long and fine, so there was no need to split them, but they needed to be separated. It was discovered that oscillating feathers with a bowstring would separate them, while soaking cocoons in hot water would extract silk fibers. An ivory cup unearthed from the Hemudu Site, engraved with insect-like patterns resembling silkworms, indicated that people at that time recognized the importance of wild silk in addition to using plant stem skins. Initially, fibers were combined by hand, but people later discovered that using the inertia of a rotating object to add twist to a long strip of fibers (called a “tuft”) was faster and more even than doing it by hand. This rotating object, made of stone or pottery, was flat and circular and was called a spinning wheel. It had a short rod inserted in the middle, known as a spindle or specialist rod, for winding and twisting the spun yarn. The combination of the spinning wheel and specialist rod was called a spinning specialist. The phrase “giving birth to a daughter while playing with pottery” in classical literature referred to girls learning to spin yarn using a spinning specialist from a young age. Spinning wheels have been found among late Paleolithic artifacts. Almost all provincial and municipal Neolithic sites in China have yielded numerous spinning wheels, with the earliest discovered in Cishan, Hebei, dating back over 5,300 years, followed by Hemudu, Zhejiang, dating back over 4,900 years. This proves that the use of spinning specialists for spinning yarn was already widespread at that time.

The technique of weaving evolved from the production of fishing and hunting nets and woven baskets used for padding. The “Xici” section in the Book of Changes records the legend of Fuxi making nets and fishing with them. Many pottery fragments from the Neolithic era bear imprints of braided objects. Fine rush mat remnants have been unearthed from the Hemudu site, and pottery with imprints of woven fabric has been found at the Banpo Village site in Shaanxi, dating back over 4,000 years. The most primitive weaving did not involve tools but was done by “hand-combing.” First, the warp threads were arranged straight by hand, and then every other thread was picked up to weave in the weft threads. The length and width of the fabric were extremely limited. Through practical experience, people gradually learned to use tools. They first inserted a stick between odd and even warp threads, known as a dividing stick, to create an “opening” between the upper and lower layers of warp threads for inserting weft threads. Another stick was used to pass a thread vertically through the upper layer of warp threads, lifting and lowering the lower layer thread by thread. By raising the stick, the lower layer of warp threads could be lifted together onto the upper layer, creating a new “opening” for inserting another weft thread, eliminating the need to pick up each warp thread individually. This stick was called a “reed rod” (made of wood) or a “reed pole” (made of bamboo). The term “reed pole” (“zonggan”) derives from this. After inserting the weft thread into the opening, a wooden sword was used to tighten and position it. One end of the warp thread was tied to a tree or pillar, while the other end of the woven fabric was wound onto a wooden stick, with both ends tied around the waist of the person. This was the primitive waist loom. The Hemudu Site has yielded components of primitive waist looms such as wooden swords, dividing sticks, and fabric winding sticks, which bear striking resemblance to ancient loom components preserved among some ethnic minorities.

Cinnabar has been found at the Liwan site in Qinghai, and stone mortars and pestles used for grinding pigments have been unearthed at Xiyin Village in Shanxi. Colorful tools have been discovered at the Jiangzhai site in Shaanxi, indicating that garments at that time were also dyed and decorated with colors and patterns.

Existing Neolithic textiles include primitive twisted silk fabric from the Chaoshan Mountain site in Wuxian County, Jiangsu, dating back 3,600 years, silk fragments (with a warp and weft density of 52×48 threads per centimeter, made from long silk fibers), silk ribbons, and hemp fabric from the Qianshan Yang site in Wu County, Zhejiang, dating back 2,700 years.

when Chinese textile was invented?

According to archaeological evidence, the customs of textile production in China can be traced back to the late Paleolithic period, approximately 20,000 years ago. The Beijing Shandingdong people, dating back to about 20,000 years ago, were already using bone needles to sew reed and leather garments. Although this primitive form of sewing is not strictly considered textile production, it can be seen as the beginning of primitive textile techniques.

The true birth and widespread popularity of textile technology and customs occurred during the Neolithic culture period. The “Yi Jing Xici” (Appended Statements on the Book of Changes) states, “The Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun wore garments, and the world was in order.” The term “garments” refers to clothing made from woven fabrics of linen or silk.

The discovery of pottery spinning wheels unearthed in the lower layers of the Dadiwan culture in Qin’an, Gansu Province, indicates that primitive textile production had already emerged in the early Neolithic period in the northwest region, with a history of approximately 8,000 years.

During the middle and late periods of the Neolithic age, primitive textile production began to flourish and show significant developments. Artifacts related to textiles can be found in cultural sites throughout the country. Some of the most important examples include:

- Hemudu Site in Yuyao, Zhejiang, dating back nearly 7,000 years. Carvings of silkworms were found on ivory cups, and traces of dual-strand linen fibers and wooden spinning and weaving tools were unearthed.

- Caoxieshan Site in Wuxian, Jiangsu, dating back approximately 6,000 years. The earliest known fabric made from ramie fibers was discovered, woven in a simple gauze-like structure using dual-strand yarns.

- Yangshang Culture site in Xiyin Village, Shanxi, where fragments of “silk-like” half cocoons, artificially split, were found in 1926, dating back over 5,000 years.

- Qingtai Site in Zhengzhou, Henan, dating back approximately 5,500 years. Linen and hemp fabric imprints, as well as remnants of silk, were found adhered to red pottery shards and skull caps. More than ten red pottery spinning wheels were also discovered, with the silk remnants being the earliest known silk textile artifacts.

- Nanyangzhuang Site in Zhengding, Hebei, dating back 5,400 years. In 1980, two pottery cocoon sculptures were unearthed, representing the earliest known pottery cocoon sculptures to date.

- Qianshanyang Site in Wuxing, Zhejiang, dating back 4,700 years. Apart from discovering several advanced flax fabric remnants compared to the gauze-like fabrics of Caoxieshan, silk ribbons, ropes, and remnants of silk fabric were also found. The weaving density, twist direction, and twist level of the silk fabrics indicate a considerable level of silk spinning techniques such as reeling, plying, and twisting.

These examples demonstrate that the technologies and customs of linen and silk weaving experienced rapid development and popularity in the middle and late periods of the Neolithic era in the Yellow River and Yangtze River regions. The discovery of Caoxieshan’s gauze-like fabric made from ramie confirms the existence of the custom of wearing “summer clothes made of gauze” during the legendary era of the “Five Emperors,” which corresponds to the Neolithic period.

who invented Chinese textile was invented?

The textile industry originated over 5,000 years ago. Legend has it that during the period of the Yellow Emperor, the emperor’s consort, Leizu, invented silk production by raising silkworms and reeling silk. This led to the emergence of silk fabric. During the Xia Dynasty, there were already slaves dedicated to raising silkworms in the royal palaces. The introduction of linen clothing came about when people discovered that fibers from plants such as hemp and ramie could be processed through techniques like hand-twisting to create suitable materials for making garments. The rise of the textile industry represented our nation’s departure from the primitive era of grass and animal skin garments, which were primarily used for protection and warmth, towards the multifunctional development of clothing and fashion, encompassing aesthetics, modesty, and deeper implications of social class.

Chinese traditional loom

Spinning Wheel

A spinning wheel is a circular disc, usually made of clay or stone, with a diameter of about 5 centimeters and a thickness of 1 centimeter. It is also known as a “spinning disk” or “spindle disk.” It has a hole in the center to insert a spindle.

During the spinning process, a length of flax or other fibers is twisted around the spindle and allowed to hang down. With one hand holding the spindle and the other hand rotating the wheel in either a clockwise or counterclockwise direction, additional fibers are continuously added, causing the fibers to stretch and twist. Once a certain length of yarn is spun, it is wound around the spindle.

Primitive Waist Loom

The primitive waist loom is one of the oldest and simplest weaving devices in the world, dating back to the late Neolithic period. Components of waist looms, such as shed blades, lease sticks, and heddle rods, have been discovered at archaeological sites like Hemudu and Liangzhu in Zhejiang, and the Guixi Spring and Autumn Period and Warring States tombs in Jiangxi. Many ceramic spinning wheels used for spinning thread have also been unearthed at the Banpo site in Xi’an, Shaanxi. After spinning a certain amount of thread on these ceramic spinning wheels, they were used for weaving fabric.

Weaving Loom

A weaving loom is a machine used to create fabric by interlacing two or more sets of yarn at right angles. It can be classified into a loom for general weaving and a jacquard loom. Examples of jacquard looms include the Zhuang ethnic group’s bamboo cage loom, the Yao ethnic group’s jacquard loom, the Miao ethnic group’s jacquard loom, the Maonan ethnic group’s bamboo cage loom, and the Dong ethnic group’s jacquard loom.

Inclined Loom Weaving Machine

A depiction of a foot-operated, heddle-pulling inclined loom can be found on a Han dynasty stone relief from Caozhuang, Sihong, Jiangsu. The inclined loom has a frame with the warp and the horizontal seat inclined at an angle of about 50 to 60 degrees. With this improvement, the weaver can sit and weave while having a clear view of the tension and continuity of the warp threads on the open shed.

Spinning Wheel

A spinning wheel is a device used to produce yarn or thread from various fiber materials such as wool, cotton, flax, or silk. It involves manual or mechanical spinning and stretching processes, using a rotating wheel and a spindle driven by hand or foot. The spinning wheel typically consists of a drive wheel and a spindle for winding the spun yarn.

Chinese spindle

Spindle, a hand tool used for spinning yarn, thread, or fine hemp rope. It consists of a small bone or wooden rod with a bamboo or iron wire hook attached in the middle. Cotton wadding, cotton yarn, or hemp fibers are fixed onto the hook, and the spindle is suspended and rotated to spin the cotton into yarn, the yarn into thread, or the hemp fibers into fine hemp rope. It is mainly used for spinning hemp rope for making shoes.

The spindle is convenient to make as it can be easily crafted from bones, such as selecting a suitable bone from the discarded ones after eating meat. Due to its simple structure and easy manufacturing process, almost every household had a spindle before the 1950s and 1960s. It is called “bodiao” in Shaanxi and Henan provinces, and “bola chui zi” in Heilongjiang province. Both the spindle and spinning wheel are tools for spinning yarn and rope, but the spinning wheel is much more complex in structure and much more efficient.

Chinese shuttle

Shuttle refers to a component on a loom that carries the weft yarn and guides it into the shuttle race. It undergoes intermittent reciprocating motion on traditional looms and continuous circular motion on circular looms.

Shuttles have been used in China since the Warring States period to the Han dynasty. Modern shuttles are typically made from materials such as persimmon wood, oak, laminated wood, or nylon. The front and back walls of the shuttle are coated with plastic or covered with hard paper as a protective layer. The shuttle chamber is often filled with materials like pig bristles, nylon threads, fur, or long plush fabric to prevent the weft yarn from unraveling. The shuttle tip is made of medium-carbon steel and undergoes heat treatment to achieve a certain level of hardness. Shuttles come in various angles between the back wall and the bottom, such as 86.5°, 87°, 88°, and 90°. The acute angle is used to improve the stability of the shuttle during flight.

The shape and structure of the shuttle are also influenced by the structure of the weft yarn, the method of repairing the warp, and the nature of the shuttle’s movement within the shuttle race. In conventional looms, the shuttle has the weft yarn inserted onto a shuttle core with spring plates, which is supported by a bottom plate spring. Automatic shuttle-changing looms have a protruding pin at the base of the shuttle core to engage with a groove in the weft pipe, aligning the probe groove on the weft pipe with the probe hole on the front wall of the shuttle to ensure the guiding function during shuttle change. In automatic weft-changing looms, the inner cavity of the shuttle is equipped with a clamp at one end to hold the bottom of the weft pipe. When changing the weft, the three steel needles at the bottom of the weft pipe are pressed into the clamp, and the weft yarn head is automatically guided into the guide eye at the top of the shuttle, while the empty tube is ejected from the bottom of the shuttle. The purpose of the sharp edge of the shuttle is to separate the warp yarns, while the flat head of the shuttle contacts with the leather to reduce wear. Shuttles used in paper felts and sack looms have a ribbed inner wall in the shuttle chamber. During operation, the empty core weft yarn is pressed into the shuttle chamber by hand and covered with a steel skin spring to prevent the weft yarn from scattering or jumping out of the shuttle chamber. Shuttles for ribbon looms have a semi-circular shape with a toothed rod at the bottom, which is driven actively by the shuttle-throwing gear. Circular loom shuttles are often in an arc shape and driven by methods such as electromagnets.

traditional Chinese textiles equipment

According to legend, textile products became commodities and developed into specialized clans engaged in textile production as early as the Xia Dynasty. By the Zhou Dynasty, there were official handcraft workshops for textile production, and internal division of labor became increasingly detailed. Flax, ramie, and kudzu became the main plant fiber materials, and technologies such as retting (soaking to remove gum) and boiling (heat dissolving to remove gum) were invented. Sericulture, reeling, and silk spinning during the Zhou Dynasty reached a high level, and reeled silk (a large twisted thread) became a standardized trade item. During the Shang Dynasty, geometric patterns were woven, and silk textiles using strong twisted silk threads were found. By the Zhou Dynasty, brocade patterns were already in use. During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, a wide variety of silk textiles were discovered, including gauze, yarn, spun silk, woven silk, gauze silk, damask, plain silk, silk crepe, and brocade, some of which were also embroidered. Colorful woolen textiles have been unearthed in places such as Nuo Mu Hong in Qinghai and various regions in Xinjiang, dating no later than the early Western Zhou Dynasty. Among these textile products, brocade and embroidery were exceptionally exquisite, making “brocade and embroidery” synonymous with beautiful things.

Based on unearthed textiles, it is inferred that by the latest during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, spinning wheels, spinning machines, foot-treadle diagonal looms, and various weaving methods involving multi-picks and jacquard patterns had already appeared. Silk, flax degumming and refining, as well as dyeing with mineral and plant dyes, were recorded in written texts. Dyeing methods included coating, rubbing, soaking, and mordant dyeing. People had mastered the technique of using different mordants to achieve different colors with the same dye. A complete range of colors was established, and feathers from five-colored pheasants were used as color samples for dyeing. Fabrics, ramie, and silk were standardized from the Zhou Dynasty, with a set width of 2.2 Chinese feet (equivalent to 0.5 meters today) and a length of 4 zhang (equivalent to 9 meters today) per bolt. Each bolt could be used to make a garment called “shenyi,” which consisted of an upper garment and connected lower trousers. It was also specified that products not meeting the standard were not allowed to be sold. This is the earliest textile standard in the world.

During the Qin and Han Dynasties, China achieved a high level of silk, flax, and wool textile technology. Hand-operated spinning wheels, spinning machines, reeling, warping tools, as well as foot-treadle diagonal looms, and well-developed multi-pick and jacquard mechanisms were widely used. Multi-color block printing also emerged. Textiles unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tomb in Changsha, Hunan Province, serve as evidence of the textile level at that time. From the Sui and Tang Dynasties to the Song Dynasty, fabric structures evolved from varying twills to satin weaves, completing the “three primary structures” (plain weave, twill weave, satin weave). The combination of multi-pick jacquard methods and multi-pick and multi-treadle mechanisms gradually spread, leading to the emergence of warp-faced fabrics with prominent warp designs. Flax textiles were widely used in people’s daily attire, while kudzu textiles became less prevalent.