Take a minute and try to come up with a list of things you can do today without money. It’s a guarantee that that list will be very short. The truth is, we have become very independent on money to get by each day. We need money to eat, to get an education, and health care. We need money to move from one place to another especially over long distances. We also need money for a start-up business. Whether directly or indirectly, we need money for a lot, so we can agree that money is important.

Money, however, is just a system through which we can acquire what we want. The paper currency used today wasn’t always in existence. Over the years, the currency has changed from barter trade to the use of coins to the paper money used today. The trendsetters of this evolution have been China. It’s been credited for inventing many of the currencies that were adopted around the world, both in the present and the past.

But have you ever held up a note and wondered how it came to be used? Have you ever wondered who invented paper money and why? In this post, we attempt to answer these questions, by discussing the origin of paper money, who invented it, and how it worked.

Who First Invented Paper Money?

It’s easy to point to Alexander Bell and credit him for creating the first telephone. It is, however, not that simple to point to one individual and credit them for inventing paper money. That’s because a group of people or more correctly, a nation, was responsible for coming up with paper money. That nation was China.

In the far past, people initially used to use bartering, where they would exchange one good directly for another, as the form of trade. Over time, people came to realize that it wasn’t easy to measure the equal worth of goods. For example, when exchanging chickens for cows, it’s difficult to gauge how many chickens were sufficient for one cow. Traders normally had to negotiate until a compromise was reached and both parties walked away satisfied.

Owing to this problem it was still the Chinese who came up with the earliest known coins as a solution to the problem. The popular coins known were mainly made of copper although there existed those made of silver, gold, and iron. The coins were mainly circular with a square hole that allowed one to string the coins making them easier to carry around. But although China developed the earliest known coin system, Lydia (today’s Turkey), a region in Western Europe is credited for being the first to use an industrial facility known as mint to mass-produce the coin currency that was used in Europe.

Why was paper money important in ancient china? Like barter trade, however, the use of coins had its downside. In large quantities, the coins became difficult to carry around especially over small distances. That was why the Chinese later came up with the first form of paper money. Initially, it was a promissory note that was used which wasn’t a true currency until the government decided to officially produce and distribute paper money as a currency. This currency was used for many years and failed and was later abolished in China by the time it got introduced to Europe. Sweden became the first country in Europe to produce and use paper money and from there it gradually became widespread all over the world.

Which Country Was the First to Use Paper Money?

Sweden was the first country to use paper money in Europe and later spread it to the rest of the world, through trade mainly and beginning with North America. Still, the fact is that China was the original inventor of paper money and so was the first country in the world to ever use paper money.

When Was Paper Money Invented in Ancient China and How Did It Work?

when was paper money invented?The use of paper money may probably date as far back as the use of paper itself. The earliest reported use of it was, however, during the Tang dynasty in 618AD. This type of paper money was first called, “flying cash” and it wasn’t an official currency. It was mainly used by rich merchants. It was known as flying cash because of its tendency to easily blow away in the wind. It was developed as a solution to carrying many coins over long distances for trade.

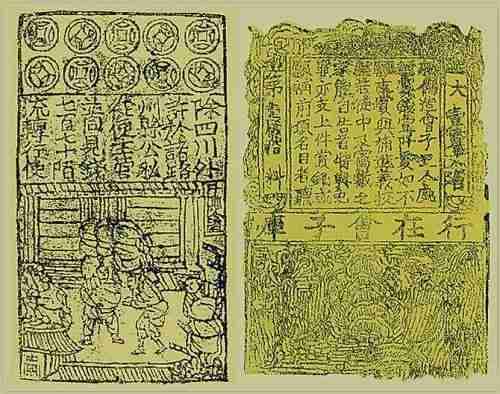

By the beginning of the Song dynasty, in Sichuan, the first printed paper money was developed by rich merchants and financiers. These notes had printed pictures of trees and people on them using red and black ink. As a way of avoiding counterfeiting, each bill had a seal of the issuing bank and a confidential mark. The notes were backed by coins, in that you could convert the notes to hard cash at any point in the issuing bank, where you got the notes. This system became quickly widespread until 1023.

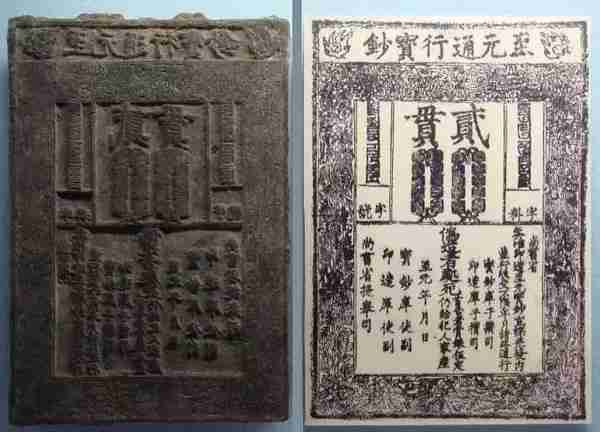

During this time, the government released an order that they were the only ones allowed to officially print paper money. As such, the Sichuan notes were withdrawn. By the 1100s, the government of the Song dynasty established factories in Anqi, Chengdu, Huizhou, and Hangzhou They were solely responsible for printing the paper money. Each factory used a different blend of fiber for their paper to avoid counterfeiting. The printing was done using wood blocks and six colors of ink.

First paper money: This new government institutionalized paper money was known as Jiaozi. It was successful because each note issued by the government was backed by hard cash. You could either exchange the notes for standard coins in any government-licensed deposit or use them to buy goods like salt in government-run shops. By this time paper money became as good as coins. This helped free more precious metal to be used in other areas.

In 1115, when the Chin occupied North China, it continued with the Song dynasty’s paper money policy. They established the Bureau of Paper Currency in Kaifeng, in 1154, to be the central body in charge of all the notes issued by the Chin. Their paper currency was divided into two denominations, the large one that consisted of one to ten strings of coins and the smaller one consisting of 1-700 standard coins. Unlike the Song dynasty’s currency, the Chin’s paper money was not backed by hard cash. This led to inflation due to counterfeiting although it was punishable by death. The currency lost its validity after seven years.

This was around the time the Yuan dynasty begun its reign under Mongol rule. In 1260, the Mongols printed their first paper money which they called Chao. Like the Chin, their currency wasn’t backed by hard cash. They produced increasing amounts of the money year in year out, leading to runaway inflation. The value of the paper money had completely depreciated. This remained the same even after the Ming dynasty came into power. By 1450, the use of paper money was dome away completely and the use of copper coins was reintroduced. It wasn’t until the 1890s, during the reign of the Qing dynasty, that new paper money called yuan, begun being printed again.

what was ancient Chinese paper money?

Ancient Chinese paper money, known as “jiaozi” (交子) or “jiaochao” (交钞), was one of the earliest forms of paper currency in the world. It was first introduced during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) but gained widespread use and popularity during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD).

The concept of paper money emerged as a more convenient alternative to carrying heavy metal coins for transactions. The use of jiaozi was initially backed by precious metals like gold or silver, and they were issued by merchants, wealthy individuals, or even local governments. These early forms of paper money were essentially promissory notes or certificates that represented a certain amount of precious metal stored with a particular issuer.

Over time, as the use of jiaozi became more common, the link to precious metal reserves became weaker, and eventually, some issuers stopped backing the paper money with tangible assets. Instead, the confidence in the value of the currency relied on people’s trust in the issuing authority and its ability to maintain stability and avoid excessive issuance.

During the Song Dynasty, the central government took over the production and issuance of jiaozi, and it became a state-controlled currency known as “jiaochao.” The Song government established regional banks to regulate the issuance and circulation of paper money, which facilitated trade and economic growth during that period.

Despite its convenience, the value of ancient Chinese paper money was not always stable due to various economic factors, including excessive issuance, lack of trust in some issuers, and fluctuations in the availability of precious metals. As a result, the use of jiaozi declined after the Song Dynasty, and it was eventually replaced by other forms of currency, such as metallic coins and later, during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, by banknotes issued by government-backed banks.

Nonetheless, the introduction and experimentation with ancient Chinese paper money played a significant role in the evolution of modern currency and influenced the development of paper money in other regions of the world.

what was ancient Chinese paper money called?

The ancient Chinese paper currency went through several stages of evolution. Initially, during the late Tang Dynasty, there was a form of currency known as “flying money” (飞钱), which served as a certificate for currency exchange and remittance. However, due to the lack of unified issuance and management, the use of flying money did not become widespread.

By the Song Dynasty, the commodity economy rapidly expanded, leading to a surge in the circulation of currency. To address the shortage of minted coins, the world’s earliest form of paper money, known as “jiaozi” (交子), was introduced. The emergence of jiaozi greatly facilitated commercial exchanges. However, due to insufficient reserves and a lack of unified regulation, the circulation of jiaozi was not effectively standardized.

In the Yuan Dynasty, an official form of paper money called “baoChao” (宝钞) was introduced, which had nationwide circulation. Baochao’s issuance and management were relatively standardized. However, issues like inflation and currency devaluation gradually eroded the credibility of Baochao.

In the Ming Dynasty, “yinpiao” ,silver notes(银票), a form of paper money backed by banks, emerged. Yinpiao had higher credibility and liquidity.

In summary, ancient Chinese paper currency went through multiple stages of evolution, with different names and characteristics during different periods.

what did ancient Chinese paper money look like?

The structural composition of ancient Chinese paper currency was primarily rectangular, varying in size, and printed using a unified process with woodblocks. The front and back sides featured the issuer’s seal, encrypted signatures, overlapping red and black ink, and three-color printing. Some currencies also had distinct layouts, patterns, and decorative elements. Additionally, certain bills were imprinted with the issuing authority, official seals, serial numbers, redemption information, and other official markings. Moreover, some notes were printed with both Mongolian and Chinese scripts, displaying distinct calligraphic styles.

what was ancient Chinese paper money made of?

The materials used for ancient Chinese paper currency initially originated from cloth, cowhide, and white deer skin, later transitioning to materials like cotton paper. However, the primary material for ancient Chinese paper currency was mulberry bark paper, known as “sangpi” (桑皮纸), which offered advantages such as soft texture, durability, and water resistance, making it the preferred choice for producing ancient Chinese banknotes.

The paper used for Chinese currency varied and included materials such as cotton paper, Korean paper (or “goryeoji”), bamboo paper, and even mulberry tree bark. Additionally, the issuance of ancient paper currency was influenced by the prevailing materials and technological limitations of the time, resulting in different production methods and materials across various dynasties and regions. For instance, during the Song Dynasty, the official currency, known as “jiaozi,” was made from mulberry tree bark. In the Yuan Dynasty, official paper money, or “baobao,” was produced using mulberry tree bark or bamboo paper. During the Ming and Qing periods, private workshops used mulberry tree bark or bamboo paper to produce currency, known as “chaopiao” (钞票).

In conclusion, the materials used for ancient Chinese paper currency underwent continuous development and change, reflecting the societal and economic progress as well as technological advancements of the respective eras.

what was the first paper money made of?

The first paper currency was made from mulberry tree bark. According to legend, in ancient Tibet, there was a small village called “Tangka,” where the villagers used mulberry tree bark to create Tibet’s first paper currency known as “Ts’a Ts’a.” It was used for exchanging goods and gradually evolved into a paper token representing currency.

what was ancient Chinese paper money used for?

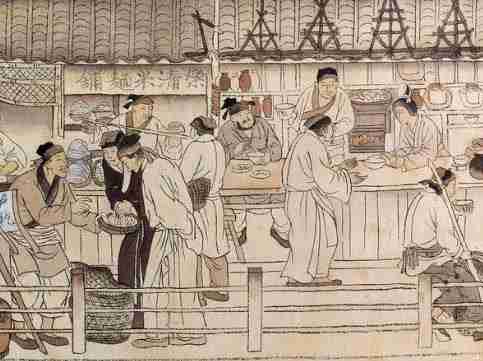

Ancient Chinese paper currency served multiple purposes, including facilitating exchange transactions for merchants, enabling bulk commodity trading, and circulating among the general public. During the Ming Dynasty, paper currency was even used to pay the salaries of princes and members of the imperial family. These various uses reflected the economic development and progression of monetary history in ancient China.

The emergence of paper currency in ancient China greatly facilitated commercial transactions and currency circulation. Merchants could conduct exchange transactions conveniently using paper currency, avoiding the burden of carrying large amounts of metallic coins. Large-scale commodity trades also benefited from the use of paper currency, making transactions more efficient. Additionally, paper currency became a convenient medium of exchange for ordinary people in their day-to-day transactions.

In the Ming Dynasty, paper currency was employed to pay the wages of princes and members of the imperial family. This transition occurred because paper currency had become the primary form of currency, with metallic coins gradually phased out of circulation. As a result, paper currency represented the value of currency and served as a payment tool in various transactions.

In conclusion, the diverse uses of ancient Chinese paper currency reflected the economic development and advancements in monetary history at that time. Its introduction provided convenience for commercial transactions and currency circulation, catering to various payment needs in different contexts.

why was paper money invented?

“Jiaozhi” (交子) was the earliest form of paper currency in China, used during the Song and Jin Dynasties. In the early years of the Northern Song Dynasty, the use of iron coins in Sichuan posed difficulties as they were small in size. For instance, 1000 large iron coins weighed 25 catties, and purchasing a bolt of silk required 90 to over 100 catties of iron coins. This cumbersome circulation prompted merchants to issue a type of paper currency called “Jiaozhi,” which replaced the use of iron coins. When exchanging Jiaozhi, 30 iron coins were deducted for each string of paper currency.

To manage the exchange business between copper coins and Jiaozhi, 16 wealthy merchants in Chengdu established Jiaozhi shops, where they printed and issued the paper currency.

The emergence of paper currency during the Northern Song Dynasty was not a coincidence; rather, it was an inevitable product of social, political, and economic development. The rapid growth of the commodity economy during the Song Dynasty increased the demand for currency in trade. However, at that time, there was a shortage of copper coins, which could not meet the growing needs of circulation. In the Sichuan region, iron coins were in circulation, but their low value and heavy weight made them highly inconvenient to use. For example, one copper coin was equivalent to ten iron coins, and the weight of 1,000 iron coins was 25 catties for large coins and 13 catties for medium coins. Purchasing a piece of cloth required 20,000 iron coins, weighing approximately 500 catties, necessitating transportation by carts. Chengdu was an important economic center, and the rugged terrain made it challenging to transport large amounts of metallic coins. Consequently, there was an objective need for a more lightweight currency, which was one of the main reasons for the early appearance of paper currency in Sichuan.

Moreover, although the Northern Song Dynasty was a highly centralized feudal autocracy, the country did not have a unified currency system. There were several currency regions, each with its own currency, not mutually interchangeable. There were 13 administrative regions using specialized copper coins, four regions using specialized iron coins, and Shaanxi and Hedong regions using both copper and iron coins. Each currency region strictly prohibited the outflow of its own currency, making paper currency an effective measure to prevent the outflow of copper and iron coins.

Furthermore, the Song Dynasty government was frequently attacked by the Liao, Xia, and Jin Dynasties, incurring significant military and reparations expenses. Issuing paper currency was necessary to compensate for the financial deficits. Various reasons led to the creation of paper currency, known as “jiaozhi.”

In summary, the introduction of paper currency was a response to the economic needs, local currency variations, and financial demands of the Northern Song Dynasty, making it a significant milestone in the history of Chinese currency.

history of ancient Chinese paper money

Paper currency, being lightweight and portable, represents an advanced form of currency. Its appearance marked a leap forward in the development of money. China was the first country in the world to use paper currency, with its use dating back to the Northern Song Dynasty and its widespread circulation during the Yuan Dynasty. “The Travels of Marco Polo” recorded the existence of mints in Dadu (present-day Beijing) that produced paper currency made from mulberry bark, which held equivalent value to gold and silver coins. As Marco Polo was a merchant, and paper currency was not yet present in the Western world, he was deeply impressed by its usage and often mentioned it when describing Chinese cities.

As early as the Western Zhou period (around the 11th century BCE), people invented “libu,” a type of currency made from cloth. It was two feet long and two inches wide, with inscriptions of the date, address, and amount, accompanied by a seal from the issuer, serving as a medium of exchange in transactions. In the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, there were “niupi bi” (cowhide coins) used in private transactions. Buyers paid the seller with a piece of cowhide inscribed with their name or a specific symbol, and the seller or another holder of the cowhide could demand payment of the cow from the buyer at any time. There was also a type of ticket called “fubie,” similar to modern promissory notes, with a line indicating the amount of money. It was divided into two halves, with each party holding one half until the maturity date when the two halves would be joined together for payment. The half held by the seller, like libu and niupi bi, could also be transferred.

During the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty, the state faced financial difficulties, so it collected deer skins from the royal gardens to create “White Deer Skin Money.” It was used as padding for jade discs when nobles and royalty met the emperor or held other significant ceremonies. Each piece of White Deer Skin Money was one foot long and one foot wide, adorned with colorful patterns and decorated with algae patterns along the edges. Its value was 400,000 coins, far surpassing the value of the jade discs, making its symbolic significance greater than its actual monetary role. As such, its circulation was quite limited.

During the Tang Dynasty, commerce was thriving, and many merchants from outside the capital Chang’an conducted business there. Carrying large amounts of coins back home was not only inconvenient but also unsafe. To solve this problem, many merchants sent their money to their home province’s official office (known as “dao” instead of “province” and “jinzouyuan” instead of “governor’s office” at the time) in Chang’an. The office issued a ticket to the merchant, specifying the amount, date, name, etc., and divided the ticket into two halves. One half was given to the merchant, while the other half was sent back to the merchant’s home province. When the merchant returned home, they could present the half ticket to the designated department to receive the money. As long as the two halves matched perfectly, the money would be paid in full. The money received by the office in Chang’an was conveniently used to offset the taxes payable to the central government. This practice was beneficial to both the public and the government, and these kinds of tickets were called “Flying Money” because it seemed as though the money was flying back and forth.

In the Tang Dynasty, “Flying Money” was not yet paper currency, but it served as the origin for the production of paper currency during the Song and Yuan Dynasties.

The real usage of paper currency began during the Northern Song Dynasty. In the second year of the Tian Sheng era of Emperor Renzong (1024 AD), China witnessed the birth of its first official paper currency called “jiaozhi.” Initially, jiaozhi was a privately issued credit exchange note that first appeared in Sichuan. The term “jiaozhi” is a Sichuan dialect, with “jiao” meaning to meet or come together and “zhi” as a suffix. During that time, Sichuan mainly used iron coins, which were lightweight but had low value. For instance, 1,000 large iron coins weighed 25 catties, and it was highly inconvenient to transport them, leading to the emergence of paper jiaozhi. Initially, individual merchants issued hand-written vouchers, and later, 16 wealthy merchants in Chengdu collectively issued copper-plate printed jiaozhi with encrypted signatures, although the amount was filled in temporarily.

Jiaozhi could be exchanged for metallic coins or directly used in circulation. However, private jiaozhi faced a credibility crisis and was subsequently abolished. In the first year of the Tian Sheng era of Emperor Renzong (1023 AD), the government established the Yizhou Jiaozhi Bureau to monopolize the issuance of official jiaozhi. The technical specifications for official jiaozhi were copied from the private ones, using three-color copper-plate printing in red, blue, and black, and they also had encrypted signatures and the official seal of the local province. Official jiaozhi had fixed denominations and a certain circulation period of three years, after which they were replaced with new notes. The issuance was limited to 1,256,340 guan per issue, with a reserve fund (chao ben). Official jiaozhi could be exchanged for gold, silver, coins, and “du die” (a type of government-issued identity card for monks, which exempted them from many taxes and could be sold for money). However, the circulation area was mainly confined to Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Hedong (present-day Shanxi region).

During the Southern Song Dynasty, various types of paper currency circulated, with “huizi” being the most prevalent. Originally, huizi was a privately issued bill of exchange, but it was later taken over by the government and became a legal currency during the 30th year of the Shaoxing era of Emperor Gaozong (1160 AD). Huizi had a rectangular shape with three-color copper-plate printing in red, blue, and black, and fixed denominations. Initially, there was only one denomination of one guan, but later, denominations of 200, 300, and 500 wens were added. The issuing authority was indicated as the “Hangzai Huizi Bureau.”

Compared to Northern Song’s jiaozhi, the role and characteristics of huizi as a national paper currency were more evident:

Firstly, huizi had a wider circulation area. Although initially limited to the vicinity of Lin’an in Zhejiang, it later expanded to regions like Huainan, Huaibei, Hubei, and western Jing, covering various southeastern routes and becoming the primary currency in circulation during the Southern Song Dynasty.

Secondly, there was a higher circulation quantity of huizi. Initially, huizi was issued in intervals of three years, with a limit of 10 million guan per period, seven times more than that of jiaozhi. In 1247 AD, the 17th and 18th periods of huizi were announced to be permanently in circulation, without any specified expiration date, and old notes could be exchanged for new ones at any time. This led to a significant increase in the quantity of huizi in circulation.

It is widely known that jiaozhi in the Northern Song Dynasty was China’s earliest form of paper currency. However, in the early 20th century, a Japanese individual claimed to have personally seen Tang Dynasty paper currency, which raises some doubts. Two examples of alleged Tang Dynasty paper currency are as follows:

The “Yonghui Chao” note during the reign of Emperor Gaozong (650-655 AD), which consisted of ten pieces. Each piece was 9 inches long and 5.875 inches wide and had a yellowish color. The paper had inscriptions of the year and month of Yonghui and phrases such as “Da Tang Bao Chao Yu Qian Tong Yong” (meaning “Great Tang Treasure Note and Silver Used Commonly”), along with two square seal impressions, one with “Yin Zao Bao Chao” (meaning “Seal of Making Treasure Note”) and the other with “Da Tang Yong Hui Zhi Yin” (meaning “Seal of Yong Hui of the Great Tang”).

The “Huichang Chao” note during the reign of Emperor Wuzong (841-846 AD), which came in two different denominations. One was worth nine guan, measuring 10.5 inches long and 7 inches wide, and the other was worth one guan, measuring 9.75 inches long and 6.25 inches wide. The paper had inscriptions such as “Da Tang Tong Xing Bao Chao Yu Yin Tong Yong” (meaning “Great Tang Currency Note and Silver Used Commonly”), among others.

ancient Chinese paper money origin

Flying Money: The Tang Dynasty was renowned for its grand canal and postal roads, which facilitated commercial transportation and connected the capital with distant provinces. To maintain strong ties with the central government, each province in China had an institution called “Jinzouyuan” (进奏院), or “Court of Memorials,” in the capital. Similar to modern lobbying organizations, these institutions served the interests of provincial governments and local officials. During the Tang Dynasty, some of these Jinzouyuan began to perform functions similar to intermediary banks.

Merchants, such as tea traders from Sichuan, sold their goods in the capital and deposited their profits in the Jinzouyuan of their respective provinces. The receipts issued by the Jinzouyuan to these merchants were known as “Flying Money” because the earned money could “fly” back to the merchants’ home provinces without having to physically transport it by land. Flying Money was divided into two parts: one half was held by the merchant, and the corresponding other half was held by the Jinzouyuan. When the merchants returned to their home provinces, they presented their half of the receipt to the government department to receive the full payment.

Government officials appreciated this system as Flying Money provided them with cash to meet the expenses in the capital. Merchants also liked the system because it eliminated their risks and the cost of transporting hard currency. Flying Money prevented the outflow of copper coins back to various provinces, increasing the currency supply in the country’s commercial center. Moreover, it became a no-interest loan service from provincial institutions. Before merchants returned to their provinces and presented the receipts, the Jinzouyuan had the right to use the cash, occasionally causing merchants to find local governments reluctant to exchange Flying Money promptly. Not surprisingly, other government agencies, such as the Ministry of Revenue and the military, also competed to offer similar services.

Unfortunately, Tang Dynasty Flying Money has not survived, so we have no way of knowing whether they were circulating notes, whether they bore dates, whether they had standardized denominations, or whether they had other functions that would shed light on their economic and financial role in Chinese society. Although we don’t know if Flying Money was used for circulation, it is difficult to imagine that they were not allocated or transferred by merchants. In this sense, they could function as currency. However, they were still unlikely to be printed as currency.

There is an interesting story about Flying Money. American collector and financial historian Andrew McFarland Davis purchased a large number of Tang Dynasty banknotes in the early 20th century. The images of these banknotes were published in a book called “On Certain Chinese Notes, Deposited in the Boston Museum of Fine Art.” Such paper money is no longer available today, and most of the banknotes obtained by Davis were likely modern forgeries, as they did not match the descriptions of Flying Money and looked more like later printed paper currency.

styles of ancient chinese paper money

There are many types of ancient paper money, which can be classified into different categories based on different periods and regions. Here are some types of ancient paper money:

Jiaozhi (交子): Jiaozhi was the world’s earliest form of paper money and was issued during the Song Dynasty in the Sichuan region of China.

Qianyin (钱引): Qianyin was an official paper currency during the Song Dynasty, issued by the official issuing authority of Jiaozhi.

Huizi (会子): Huizi was a paper currency during the Southern Song Dynasty, issued by the official issuing authority, initially serving as temporary paper money but gradually becoming a widely used currency.

Yuanbao Chao (元宝钞): Yuanbao Chao was a paper currency during the Yuan Dynasty, with the yuanbao as the main currency and silver as the subsidiary currency.

Baochao (宝钞): Baochao was a paper currency during the Ming Dynasty, issued by the official issuing authority, with copper coins as the main currency and paper money as the subsidiary currency.

Jiaochao (交钞): Jiaochao was a paper currency during the Jin Dynasty, issued by the official issuing authority.

Yinpiao (银票): Yinpiao was a paper currency during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, issued by private financial institutions such as money shops and silver shops, which could be exchanged for metallic currency.

The above are some types of ancient paper money, and there were other types in different periods and regions. The emergence of these paper currencies reflects the economic development and progress of monetary history during those times.

who invented ancient Chinese paper money?

Jiaozhi (交子) was a currency issued in the first year of the Tianfu reign (1023 AD) during the Northern Song Dynasty in China. It is considered the world’s earliest form of paper money. The initial inventor of Jiaozhi was Zhang Yong, the prefect of Chengdu. Jiaozhi came in various denominations from one guan to ten guan, and the value was filled in when issued. Later, it was changed to be printed with fixed denominations of five guan and ten guan, and then further modified to one guan and five hundred wens. The issuance had a fixed quota, with a new edition every two years, and the old notes were replaced with new ones at the end of each term, strictly prohibiting private counterfeiting.

According to the Qing Dynasty’s “Continuation of Tongdian – Food and Currency,” Jiaozhi had an interval of three years. Its inception was due to the inconvenience of using both copper and iron coins during the Song Dynasty. During Emperor Shenzong’s reign, Jiaozhi was officially recognized by the authorities, and forging Jiaozhi was equated with forging official documents.

Zhang Yong (946-1015), also known by his courtesy name Fuzhi and the pseudonym Guaiya, was born in Juancheng County, Puzhou (present-day Juancheng County, Heze City, Shandong Province). He was known for his exceptional skills in both swordsmanship and literary arts. Zhang passed the imperial examination and began his official career. His experiences of being poor and excelling in martial arts and literature shaped his unique character and unorthodox approach to handling matters, often standing out from the crowd.

At the age of 35, Zhang Yong passed the imperial examination and was appointed as the county magistrate of Chongyang County in Ezhou. In the fifth year of Chunhua reign (994 AD), Zhang Yong arrived in Shu region and served as the prefect of Chengdu. Sichuan was a prosperous province known as the “Land of Abundance,” but it suffered from a shortage of copper, leading to the use of iron coins as currency. However, the value of iron coins was low, making transactions with large amounts of money extremely inconvenient. Recognizing this problem, Zhang Yong boldly invented the earliest form of paper currency known as “Jiaozhi.” According to the “History of the Song Dynasty – Food and Currency,” it was mentioned that “Zhang Yong governed Shu and was troubled by the weight of iron coins among the local people, which inconvenienced trade. He introduced the system of quality exchanges, one for one, with three years as a cycle.”

The term “Jiaozhi” is a local term in Sichuan, meaning a ticket or voucher. “Jiao” implies coming together, suggesting a ticket that combines and takes money. The initial Jiaozhi was printed using wooden blocks, later switching to copper blocks, on mulberry paper. It was based on the value of iron coins and initially ranged from one guan to ten guan, with the specific amount filled in at the time of issuance. Eventually, the denominations increased, and fixed denominations were printed.

The application of paper money in the history of currency was undoubtedly revolutionary. Due to technological factors such as paper and printing, it took six centuries for Europe to adopt paper money after its emergence in China. Therefore, Jiaozhi, invented by Zhang Yong, was not only China’s earliest form of paper currency but also the world’s earliest. Zhang Yong is revered as the father of paper money.

The raw material used for the paper of China’s earliest paper money was derived from mulberry trees. As a commemoration, there is a rare Chinese mulberry tree planted in a courtyard of the Bank of England in London.

what dynasty was paper money invented in china?

Paper money was invented in China during the Tang Dynasty. It is believed that the first recorded use of paper money occurred around the 7th century AD, specifically during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty. However, these early forms of paper money did not gain widespread acceptance and were used in limited areas and for limited periods.

The true development and widespread use of paper money as a regular form of currency took place during the Song Dynasty. The Jiaochao (交钞), also known as Jiaochao Jiazi (交钞甲子), issued in 1023 AD during the Northern Song Dynasty, is considered the world’s earliest documented and widely circulated paper currency. It was a significant step forward in the history of paper money and played a crucial role in the economic development of China.

ancient Chinese paper money

The “Bailu Pibi” was suggested by Zhang Tang to Emperor Han Wu during the Han Dynasty. Its style and purpose are recorded in the “Book of Han, Volume on Food and Money.” The idea behind the “Bailu Pibi” was related to the ancient customs of presenting jade bi as gifts when members of the imperial family and nobles paid respects to the emperor. However, the jade bi couldn’t be presented without proper packaging, and “Pibi,” meaning “leather token,” was used as a cushion for the jade bi. The “Pibi” had to be made from the skin of white deer.

The term “Pibi” had existed since ancient times and was used as valuable tribute presented by vassals to the Zhou king or as gifts exchanged among upper-class nobles. However, the interpretation of “Pibi” as a form of currency is incorrect. In this context, “Bi” refers to woven cloth or textile, not currency. The ancient character for “Bi” was written as “幣,” and the dictionary from the Han Dynasty, “Shuowen Jiezi,” explains it as “幣, 帛也. 从巾, 敝声,” which translates to “Bi is cloth, and its radical is ‘巾’, and ‘敝’ indicates the pronunciation.” It refers to woven fabrics that were often rolled up, also known as “shufu,” and were commonly used as gifts among nobility during the pre-Qin period. Therefore, “Pibi” refers to a type of gift or tribute, specifically used for exchanges among upper-class nobles.

During ancient times, valuable gifts presented as tribute were not limited to woven cloth; precious jade artifacts were also highly regarded. Jade has been revered in China since ancient times, with various types of jade objects, such as small jade pendants worn by nobles and larger ones symbolizing political authority, like jade yue (battle-axe) representing the ruler’s power, and jade guang, jade bi, and jade zhang used for exchanges among nobles.

During the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods, noble interactions were highly focused on rituals and ceremonies. However, during the Warring States period, the disintegration of traditional customs and the constant warfare led to the abandonment of many ceremonial practices. When Liu Bang established himself as the Emperor of China, many of his followers who were promoted to nobility were from the lower classes and lacked knowledge of proper court etiquette. This displeased Liu Bang, who desired to establish a more sophisticated court culture. It was only after he sought the advice of Confucian scholar Shusun Tong, who was well-versed in traditional rites and rituals, that Liu Bang successfully implemented court protocols. This moment is famously known as “I now know the importance of being an emperor.”

During Emperor Wu’s reign, the nation was still recovering from wars, and his primary concern was dealing with external threats like the Xiongnu, which required significant financial resources. It was only after major military victories and the subjugation of the Xiongnu in 119 BCE that Emperor Wu focused on strengthening internal governance, including the restoration of traditional rituals. In light of the historical lessons from the Rebellion of the Seven States, suppressing the power of the imperial family and nobles became a core aspect of the revival of rituals. Emperor Wu accepted Zhang Tang’s proposal to issue the “Bailu Pibi” under the pretext of restoring and strengthening court rituals. This allowed the imperial court to collect wealth from the nobles and regional lords while filling the imperial treasury. The issuance of the “Bailu Pibi” served to reinforce imperial authority and weaken the power of the imperial family and nobles, effectively combining the objectives of accumulating wealth and restoring traditional rituals.

The “Bailu Pibi” had a specific value of 400,000 units, but it was not considered a form of currency and could not be transferred like modern money. Instead, it served as a ceremonial item with a designated price, functioning as a means of tribute and symbolizing the relationship between the imperial court and the nobility. The practice of using deer skin (not necessarily white deer) for ceremonial purposes continued during the Wei Dynasty. China’s ancient monetary system went through various stages before the development of standardized paper currency during later dynasties.

Issuing the “Bailu Pibi” served a dual purpose and was seen as a favorable action. Finding white deer for this purpose was not difficult, as the imperial royal park, the “Shanglinyuan,” specifically raised white deer. White deer were actually a rare mutation of the spotted deer, and the appearance of white deer was considered an auspicious sign. When white deer were discovered, they were required to be offered to the emperor as sacrifices and were exclusively raised in the imperial royal park for this purpose. Thus, during Emperor Han Wu’s reign, the “Shanglinyuan” kept white deer, and the Court Treasury, known as “Shaofu,” would have the white deer’s skin cut into squares, adorned with colorful patterns, and valued at 400,000 units each. It was mandated that when members of the imperial family and nobles paid respects to the emperor, they must purchase “Bailu Pibi” made from the skin of the white deer from the imperial royal park to be used as cushions for the jade bi offered as tribute. However, this practice was not truly a gift but rather a compulsory revenue collection scheme.

Historical records document that Emperor Han Wu initially consulted with Yan Yi, the head of agriculture, about the idea of issuing the “Bailu Pibi.” Yan Yi, known for his honesty, remarked that the value of the gifts typically presented by nobles during their visits was only worth thousands of units, whereas the cushions made from white deer skin were valued at 400,000 units each. He considered this discrepancy to be “inappropriate.” Emperor Han Wu was displeased with Yan Yi’s response. Subsequently, Yan Yi faced accusations on unrelated matters and was judged by Zhang Tang, who held grudges against Yan Yi. Zhang Tang used the charge of “fúfěi” (internal slander), accusing Yan Yi of secretly criticizing the court, similar to the fabricated charges against the historical figure Yue Fei by Qin Hui during the Southern Song Dynasty. Zhang Tang, using Emperor Han Wu’s authority, sought revenge and had Yan Yi killed. This event led Sima Qian, the historian, to express his lament in “Records of the Grand Historian,” stating, “Since then, there have been laws punishing internal slander!”

Although the “Bailu Pibi” itself had no inherent value and did not function as actual currency, the fact that a square piece of deer skin was valued at 400,000 units made it comparable to large-denomination paper money in terms of nominal value. Therefore, it can be argued that, in a way, the “Bailu Pibi” served as a precursor to ancient Chinese paper currency and holds significance in the history of Chinese currency, marking the origin of paper money.

The exact date of the discontinuation of the “Bailu Pibi” valued at 400,000 units is not known. However, the practice of offering bi made from deer skin continued as a common custom. According to the “Book of Later Han,” during the Cao Wei period, when vassals paid respects, they still adhered to the practice of offering bi made from deer skin, although it was no longer explicitly required to use white deer skin.

tang dynasty paper money

“Feiqian,” also known as “bianhuan” or “bianqian,” was a form of exchange and remittance during the Tang and Song dynasties in ancient China. It can be translated as “flying money” because it allowed merchants to transact without physically transporting large amounts of coins, as if the money had wings and could “fly” between locations. However, it’s essential to note that “feiqian” was not a true form of currency but rather a form of exchange or promissory note used in money exchange transactions.

During the Tang Dynasty, there was a shortage of coins in circulation, and restrictions were placed on the export of coins from various regions. When merchants visited the capital city (Changan during the Tang Dynasty), they entrusted their money to the local agencies known as “jinzhou” (进奏院), stationed in the capital or various military outposts and regional governors (“zhujun” and “zhushi”). These agencies or wealthy merchants issued half of a certificate (lianquan) to the merchants, while the other half was retained by the issuing agency. The merchant would then travel back to their home region, where they could redeem the money by presenting the matching half of the certificate. This exchange process became known as “feiqian” or “flying money.” The purpose of this system was to facilitate trade and reduce the risks and inconvenience of carrying large amounts of coins during commercial activities.

The “feiqian” system continued to evolve during the Song Dynasty. In the early years of the Southern Song period, the “feiqian” business thrived, with specific offices established to handle these exchanges. Later on, with the introduction and increased use of paper money, the “feiqian” system gradually declined.

It is important to understand that “feiqian” was essentially an exchange or remittance operation and did not directly participate in daily circulation or function as an independent form of currency. Instead, it facilitated the movement of money between regions, similar to modern-day bank drafts or remittance systems. Therefore, it should not be considered as a true form of paper currency.

song dynasty paper money

The Song Dynasty was a period of great prosperity in various aspects such as the economy, culture, and technology, and its economic output ranked among the top in the world during that time. However, due to the developed commodity economy and frequent circulation of currency, the government faced challenges in effectively managing the vast and complex currency system. As a result, the government issued “jiaozhi” (交子) as a unified currency under central management.

Jiaozhi was a type of credit currency issued by the government at that time, jointly issued by merchants and salt merchants in Chengdu. Its primary purpose was to serve as a settlement tool for commercial transactions in China. Jiaozhi came in various denominations, such as five wens, ten wens, one hundred wens, five hundred wens, one thousand wens, five thousand wens, and ten thousand wens. Jiaozhi was based on copper as the value unit, with ten wens being equal to one guan, which was the standard unit of currency in circulation at that time, making jiaozhi a standard measure of commodity value.

During the issuance of jiaozhi in the Song Dynasty, it was stipulated that either copper yuan households or a certain number of copper coins could be exchanged for one guan of jiaozhi, along with an additional silver coin. As time passed, the government changed the face value of paper money to one guan, ten guan, or one hundred guan during the Southern Song period. At that time, paper money offered significant convenience compared to copper coins in terms of usage.

During the early Northern Song period, the extensive use of metallic currency led to severe inflation. However, in the Southern Song period, due to the government’s implementation of paper money policies and fiscal pressures, inflation worsened. The combined effect of these factors made the Southern Song period the most prosperous economically, socially stable, and culturally flourishing era in ancient China.

Development of Jiaozhi in the Northern Song:

During the Song Dynasty, the government issued some paper money, primarily for conducting commercial transactions. However, the extensive circulation of paper money in the currency market severely hindered commodity exchanges, making it difficult to conduct trade. To address this currency issue, the government introduced paper money known as jiaozhi during the early Northern Song period.

Jiaozhi, as a commercial credit currency, not only served as a means of payment settlement in commercial transactions but also provided a measure of commodity value. It was popular among merchants due to its convenience, durability, non-perishable nature, and resistance to devaluation. As the quantity of government-issued paper money increased during the mid to late Northern Song period, the government began implementing policies to replace copper coins with jiaozhi to address the increasingly severe fiscal deficits.

In the late Northern Song period, the government faced significant financial deficits. To address these issues, the government started issuing paper money known as jiaozhi. However, due to a lack of proper management measures and supervision mechanisms during the issuance, depreciation and inflation of the paper money often occurred.

During the transition from the late Northern Song to the early Southern Song period, the government’s ineffective management of paper money resulted in severe inflation. As a consequence, currency depreciation and inflation worsened due to soaring commodity prices. Additionally, the arbitrary increase and excessive issuance of paper money by the government led to issues such as an excessive money supply, a wide variety of currency types, and slow currency circulation.

Development of Jiaozhi and the Paper Money System in the Southern Song:

During the Song Dynasty, the issuance of paper money was strictly regulated, employing a combination of central and local management. The central government was responsible for supervision and management, while local governments handled tax collection. The aim was to prevent local officials from arbitrarily issuing paper money, ensuring that paper money retained its proper value and function.

During the reign of Song Taizu, the government was already aware of this issue. Song Zhenzong also made efforts in this regard by declaring that jiaozhi would be issued by the central government and that merchants and salt merchants would be responsible for the issuance. However, during the reign of Song Renzong, he promulgated laws prohibiting merchants and salt merchants from issuing jiaozhi, instead replacing it with government-issued paper money. However, these measures during the reign of Song Renzong did not have a significant impact in reality.

After the establishment of the Southern Song Dynasty, Song Gaozong began to work on financial reform. His measures included abolishing jiaozhi, chaofa, and huizi, the three types of paper money used during the Song Dynasty. In the early Southern Song period, to maintain financial stability, he took steps to abolish jiaozhi, chaofa, and huizi. Subsequently, the issuance of paper money was directly monopolized by the government.

The practice of unified government issuance of paper money did not yield the expected results. On the contrary, due to an excessive money supply, inflation became a significant issue. While the government temporarily abolished jiaozhi for a period, it later resumed issuing paper money. Frequent changes in paper money led to a severe rise in prices.

In the mid to late Southern Song period, as the financial difficulties of the Southern Song government worsened, Song Gaozong ordered the reintroduction of jiaozhi, chaofa, and huizi, the three types of paper money. The issuance of these three types of paper money in the mid to late Southern Song period was implemented as a measure to address the financial crisis at that time. As jiaozhi was a credit currency issued by the government based on copper as the currency unit, it did not possess the characteristics of metallic currency, such as convertible value and transferability of use value.

Moreover, after the issuance of jiaozhi, chaofa, and huizi during the Northern Song period, the Song Dynasty government resumed issuing jiaozhi chaopiao and huizi chaopiao. The Southern Song government combined the use of paper money with metallic currency, allowing paper money to play a significant role in economic life. As a result, a multi-currency system centered on jiaozhi chaopiao, chaofa, and huizi chaopiao emerged in the Southern Song period.

inflation

In the second year of Song Renzong’s Qingli reign (1042 AD), there was a severe inflation in the Sichuan region, with rice prices soaring to a thousand coins per stone, while the price of iron coins reached several thousand coins per stone. Among these, the price of copper currency increased the fastest, as the price of iron currency only rose and did not fall. The government issued an order to prohibit the private casting of copper coins, but some merchants continued to use copper to mint coins, and eventually, there was even a phenomenon of the Copper Bureau selling copper. This led to an imbalance in the ratio between copper and silver, resulting in severe inflation.

During the Northern Song period, the price of silver was very high. In the second year of Xining (1069 AD), one tael of silver exchanged for one ingot of silver, and the price increased more than three times from the third year of Xining to the seventh year of Xining over five years. Iron coins were cast from copper, making them even more susceptible to causing inflation. From the Northern Song period to the end of the Southern Song period, prices remained in a continuous upward trend.

The inflation during the Northern Song period was due to the large issuance of metallic currency and the nature of metallic currency itself. Starting from the early Northern Song period, a large number of copper and iron coins were issued as circulating currency, with an excessive quantity of issuance. According to official records at that time, over 36 million guan of copper coins were issued during the Jiayou period. Subsequently, a large number of iron coins were issued for minting, coinage, and casting, far exceeding previous levels.

During the Northern Song period, the government did not strictly limit the issuance of paper money, and a large number of paper currencies flooded the market, significantly exacerbating inflation. When the issuance of paper money exceeded the needs of economic development, inflation would occur. In the fifth year of Song Shenzong’s Yuanfeng reign (1082 AD), the government began to prohibit private coinage and restricted the minting of copper, but some regions still minted copper and iron coins. By the sixth year of Xining (1073 AD), the government ordered the prohibition of private copper coinage, iron coinage, and lead coinage. This led to a reduction in copper and iron currencies and other metallic currencies in circulation. From the sixth year of Xining to the seventh year of Yuanfeng (1074-1084 AD), the government strictly limited private coinage, resulting in nearly halved coinage, and there was also a reduction in the issuance of paper money.

The Southern Song government used jiaozhi as the legal currency for issuance and circulation. As the Southern Song Dynasty had implemented paper money policies for decades, the people were already familiar with and trusted paper money. Additionally, it was a measure taken due to the significant financial pressure faced by the Southern Song government. However, when issuing paper money, the Southern Song government did not take into account factors such as fluctuations in the prices of metallic currencies in circulation and the devaluation of metallic currency itself. This resulted in a large amount of paper money circulating and causing serious inflation.

yuan dynasty paper money

Apart from the Song Dynasty, the Jin Dynasty also issued paper money called “Jiaochao.” Although the commerce in the Jin Dynasty was not as developed as in the Song Dynasty, their control over the issuance of paper money was well-regulated. The Jin Dynasty implemented a rule that allowed paper money to circulate indefinitely. If the text on the notes became difficult to discern, people could exchange them at the corresponding government agencies for new ones. In the Jin Dynasty, there was sufficient copper currency as a backing for the currency issuance, which prevented inflation, and the exchange rate between Jiaochao and copper coins was maintained at 1:1 for a long time.

During the Yuan Dynasty, they established the most sophisticated paper money system in the world, building upon the foundation laid by the Jin Dynasty. At the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty, each province was required to prepare sufficient reserves, and then they issued a universally accepted national currency called “Zhongtong Chao.” The Yuan government allowed the public to exchange paper money at any time. They imposed severe penalties on counterfeiters and regularly updated the circulating paper currency in the market. However, due to frequent wars and financial crises later in the Yuan Dynasty, they resorted to excessive issuance of paper money, which eventually led to inflation.

ming dynasty paper money

The historical background of Ming Dynasty’s paper money can be traced back to the Tang and Song Dynasties, where paper money was also used. However, during the Ming Dynasty, there was a more urgent need for a currency form that was easy to circulate, manage, and control due to economic development and financial demands. Therefore, at the beginning of the establishment of the Ming Dynasty in 1368, they began to implement a paper money system and gradually replaced the previous use of physical currencies such as copper coins. However, due to excessive issuance, it led to inflation problems and lacked effective regulatory mechanisms, resulting in numerous crisis events over the next few hundred years, eventually leading to the collapse of the system when the government lost credibility or became unstable. Nevertheless, Ming Dynasty’s paper money still had a significant impact on China’s financial system throughout history and laid the foundation for future reforms and opening-up.

Officially issued during the Ming Dynasty, Hongwu 8th year (1375). It was made of cotton paper, thick like a coin, and had a bluish color. The format was square, measuring one foot high and eight inches wide. The outer border was framed by ink lines, with “Da Ming Tong Xing Bao Chao” written horizontally above, and a dragon-patterned border below. A horizontal ink line divided the center into two sections. Above the line, the characters “Yi Guan” were written, with a coin-like shape below. On both sides, there were eight seal characters: “Da Ming Bao Chao, Tian Xia Tong Xing” (Da Ming Treasure Note, Circulating Nationwide). At the bottom, seven lines of fine characters read: “Zhong Shu Sheng (Changed to Hu Bu after the 13th year), authorized by the Central Secretariat, printed Da Ming Bao Chao, used in circulation with copper coins, counterfeiters will be executed, and informants will be rewarded with 250 taels of silver, as well as the confiscation of the offender’s property. Hongwu year, month, and day.”

The reverse side featured a floral pattern border at the bottom, with “Yi Guan” written horizontally above, also with a coin-like shape below. A red seal was used to identify the note. The denominations of the notes included Yi Guan, Wu Bai Wen, Si Bai Wen, San Bai Wen, Er Bai Wen, and Yi Bai Wen, with the same design but varying horizontal characters and coin shapes according to the denomination.

In the seventh year of Hongwu (1374), Zhu Yuanzhang ordered the establishment of the Bao Chao Ti Ju Si as the institution responsible for issuing and producing paper money. The following year, he decreed, “the Central Secretariat is authorized to print Da Ming Bao Chao, to be used in circulation by the public.” Da Ming Bao Chao was made of mulberry bark, measuring one foot high and six inches wide, with a bluish color and a dragon-patterned floral border on the outer side. The characters “Da Ming Tong Xing Bao Chao” were written on top, and eight seal characters on both sides read “Da Ming Bao Chao, Tian Xia Tong Xing” (Da Ming Treasure Note, Circulating Nationwide). The center depicted several strings of copper coins.

To prevent private counterfeiting, Da Ming Bao Chao carried the inscription, “authorized by the Central Secretariat to print Da Ming Bao Chao, used in circulation with copper coins, counterfeiters will be executed, and informants will be rewarded with 25 taels of silver, as well as the confiscation of the offender’s property.” With this punishment stipulated, Ming Dynasty established a system of “large amounts in banknotes, small amounts in coins, and the coexistence of banknotes and coins.” Moreover, the use of gold and silver in trade was forbidden, and violations were subject to punishment.

However, by the time of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, silver had gradually become a commonly used currency, and people held some gold and silver. Recognizing this, while prohibiting the circulation of gold and silver, Zhu Yuanzhang also set the exchange rates between gold and silver and Bao Chao, “one guan of Bao Chao is equivalent to one thousand wens of coins, or one tael of silver, four guans are equivalent to one tael of gold.” In this way, people’s gold and silver were exchanged by the court for Bao Chao, but they could not exchange Bao Chao back to gold and silver with the court.

Ming emperors, including Zhu Yuanzhang, had no financial knowledge, and when issuing Da Ming Bao Chao, they lacked corresponding reserve funds, resulting in a continuous decline in the value of Bao Chao. During the reign of Zhu Di, in order to pay for large fiscal expenditures, he excessively issued Bao Chao, accelerating its depreciation. “As a result, prices soared, and the currency system worsened without functioning.” Furthermore, Ming Dynasty also implemented the “Dao Chao Law” where people were required to pay a certain “processing fee” when exchanging old notes for new ones, leading to a large accumulation of old notes and accelerating depreciation.

By the eighth year of Hongwu, one guan of Bao Chao was equivalent to one thousand wens of coins. However, by the twenty-third year of Hongwu, one guan of Bao Chao could only be exchanged for two hundred and fifty wens of coins, and four years later, it was only worth one hundred and sixty wens of coins. By the twentieth year of Yongle, the value of Bao Chao had depreciated further, “one guan of Bao Chao could not even be exchanged for one wen of coins.” People even ignored Bao Chao when it was dropped on the ground. The Ming court had no solution, ultimately canceling the prohibition of silver, and “both the court and the public began to use silver, with small amounts using coins, and only for official salaries they used Bao Chao.” After all the turmoil, Ming Dynasty eventually returned to the “silver era.”

qing dynasty paper money

During the Qing Dynasty, the printing of official tickets from the Ministry of Revenue (户部官票) and the Great Qing Treasure Notes (大清宝钞) was mainly done using woodblock or copperplate printing, similar to the methods used in the Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties. The banknotes were in a vertical square format and larger in size. Although they were printed in two or three colors, the color schemes were relatively simple, and the printing technology was not very complex. As a result, they were often easily imitated by the general public.

Apart from the government-issued Ministry of Revenue tickets and Great Qing Treasure Notes, private banks and money exchange shops in the late Qing Dynasty also issued banknotes. The private money exchange shops had various names, such as money shops, money dealers, and silver shops, and they were part of the local financial industry. Their main business was exchanging silver coins and issuing banknotes and silver certificates, playing a role in complementing the minting of coins and silver ingots and acting as a means of payment.

During the Qing Dynasty, there were several types of banknotes issued by the government, each with its historical background:

Shunzhi Chao Guan (顺治钞贯): This was the earliest paper money issued during the Qing Dynasty by the government for exchanging copper coins, maintaining a certain exchange rate with metallic currency. Its issuance marked the beginning of Qing Dynasty’s paper money.

Da Qing Bao Chao (大清宝钞): One of the most important banknotes during the Qing Dynasty, issued by the Ministry of Revenue for exchanging silver taels, also maintaining a fixed exchange rate with metallic currency. The issuance of Da Qing Bao Chao made paper money an auxiliary currency to silver taels, further promoting economic development.

Hu Bu Guan Piao (户部官票): Another significant type of paper money issued during the Qing Dynasty, also issued by the Ministry of Revenue. The key difference between Hu Bu Guan Piao and Da Qing Bao Chao was that the former was used exclusively for government financial expenditure, while the latter was more widely used in commercial transactions.

Da Qing Yin Hang Dui Huan Juan (大清银行兑换券): This was another important type of banknote issued towards the end of the Qing Dynasty, issued by the Great Qing Bank. Its issuance made banks the main issuers of currency, further promoting the development of the financial industry.

In summary, the types of banknotes issued during the Qing Dynasty were relatively limited, mainly used for exchanging metallic currency and government financial expenditures. Nevertheless, the introduction of paper money marked a significant advancement in Qing Dynasty’s monetary history, laying the foundation for the development of paper money in the future.

Reform:

In the twenty-first year of Guangxu’s reign (1895), Japan invaded Taiwan, and the Chinese general Liu Yongfu led the people of Taiwan in a resistance movement. During this period, the Official Silver Money Bureau was established in Tainan, and Tainan Official Silver Notes were issued. The value of these notes was equivalent to the silver coins in circulation in Taiwan at the time, mainly used to raise military funds and support the resistance against the Japanese invaders.

At the same time, Western powers introduced Western currencies into China while invading militarily and also printed banknotes for local and private banks in China. These banknotes featured advanced modern printing techniques, exquisite artwork, and precise printing, which caught the attention of knowledgeable officials in the Qing government. Some government officials who advocated reforms promptly advised the court to introduce Western advanced banknote printing technology and issue paper money in China to meet the economic needs of the Qing government at the time.

In the thirty-second year of Guangxu’s reign (1906), the Ministry of Revenue (later renamed the Department of Treasury) dispatched personnel to Japan to study banknote printing technology and presented a memorial to the court proposing the establishment of an official printing bureau. The memorial stated, “…to understand that the purpose of paper money is for the convenience of commerce and finance… countries in the East and the West regard the issuance of paper money and all kinds of official documents with monetary value as the government’s responsibility, strictly preventing private forgery… as the Ministry is currently in charge of financial reorganization, it is most appropriate to consider and adopt these measures, and lay the foundation.” Consequently, in 1907, the personnel who returned from their investigation submitted another memorial to the court proposing the establishment of the official printing bureau.

In 1907, the Qing government approved the memorial from the Ministry of Revenue, and preparations for the establishment of the “Ministry of Revenue Printing Bureau” began. At that time, the United States was at the forefront of banknote printing with its steel engraving intaglio technique used by American Bank Note Company. Therefore, the Qing government sent personnel to the United States to study and determine the scale and level of the National Bureau of Engraving in America, and decided to build China’s official printing bureau accordingly.

how did ancient china make paper money?

The production methods of ancient paper money differed from modern banknotes due to the absence of modern papermaking and printing technologies. Here are some methods used to create ancient paper money:

Material Preparation: Ancient paper money mostly utilized plant fibers as pulp, such as tree bark, hemp stalks, bamboo, and other plant materials.

Pulping: Plant fibers were crushed and pounded into pulp, removing impurities and color.

Water Dilution: The pulp was diluted with an appropriate amount of water to achieve a thin and manageable consistency.

Sheet Formation: The diluted pulp was poured into a papermaking frame and underwent processes like filtration and dehydration to create paper sheets.

Printing: Designs and text were printed onto the paper money using various techniques, such as woodblock carving, metal casting, or stone carving.

Anti-Counterfeiting Measures: To prevent counterfeiting, ancient paper money often included special anti-counterfeiting features, such as official seals, watermarks, or distinctive fibers.

In summary, the production methods of ancient paper money were relatively intricate, involving multiple steps to create the final product. Despite this complexity, ancient people still successfully used these paper notes for transactions and currency circulation.

how did paper money work in ancient china?

Ancient paper currency Security

In ancient times, paper money had several anti-counterfeiting measures to ensure its authenticity and effectiveness, maintaining its reputation and stability. These measures included:

Material Security: Special materials were used to make the paper money, making it difficult to counterfeit. For example, the use of rare plant fibers or the addition of unique chemical substances.

Printing Security: Complex patterns, designs, texts, and other elements were printed on the paper money to make it challenging to replicate. This involved the use of official seals, special fonts, colors, etc.

Official Seals: Official seals were affixed on the paper money, making it difficult to be forged. These seals were typically made by officially recognized seal engravers, making them hard to duplicate.

Limited Use Period: The paper money had a specified period of validity, after which it would become unusable, preventing counterfeiting and theft.

Strict Punishment for Counterfeiting: Stringent laws were enacted to impose severe penalties on those involved in counterfeiting paper money. This acted as a deterrent and safeguarded the credibility of the currency.

In summary, ancient paper money’s anti-counterfeiting measures involved the use of special materials, intricate printing techniques, official seals, limited use periods, and strict punishment for counterfeiters to ensure the authenticity and effectiveness of the currency, thus maintaining its reputation and stability.

Firstly, in ancient times, similar to modern times, there were specialized institutions responsible for issuing and producing paper money. The government was responsible for issuance, while paper mills were responsible for manufacturing and supplying the paper, specifically using a type of paper known as “Mitsumata paper.”

Mitsumata paper was made from high-quality Mitsumata tree fibers and was not readily available to everyone. Purchasing it required approval from the authorities. To prevent skilled individuals from engaging in counterfeiting, the government employed specific measures. Not only did they appoint officials to oversee the process, but there were also suggestions to gather experienced workers in designated areas and maintain strict control over the supply of paper, ensuring that these skilled individuals would not engage in counterfeiting.

Secondly, when the government issued paper money, it was stamped with official seals from higher authorities down to the provincial and county levels. By the time the paper money reached the money exchange centers, it would have accumulated several seals, and the exchange centers would add their own seal as well. The multiple seals increased the cost of counterfeiting.

In addition to the layers of official seals, intricate and elaborate designs on the paper money were vital for preventing counterfeiting. These designs were intentionally complex to deter any attempts at imitation, even by skilled artisans.

For example, during the Song Dynasty, the paper money featured patterns depicting flowers, plants, trees, birds, and houses, aligning with the artistic emphasis on floral and bird motifs in that era. However, in later periods such as the Yuan and Qing Dynasties, the designs became more intricate, incorporating elements like ornate borders, reflecting the prevailing artistic trends and social environment.

Finally, once the anti-counterfeiting measures were implemented on the paper money, enforcing strict laws became crucial. Severe penalties served as a deterrent. For instance, during the Yuan Dynasty, a warning phrase “Counterfeiters will be executed” was prominently printed on the paper money. The Qing Dynasty also had strict regulations, declaring that anyone involved in counterfeiting, including those who planned it, carved the printing plates, printed the money, made the paper, provided materials, or facilitated the process, would all face the punishment of death.

In summary, the anti-counterfeiting measures of ancient paper money involved using special materials, applying layers of official seals, intricate designs, and enforcing strict laws to ensure the credibility of the currency and deter counterfeiters.

why was paper money important in ancient china?

Paper money was of great significance in ancient China for several reasons:

The emergence of paper money resolved the problem of insufficient copper coins. With economic development and expanding trade, there was an increasing demand for copper coins. However, the production of copper from official copper mines was inadequate, and the high cost of casting copper coins limited their usage. The introduction of paper money addressed this issue, making transactions more convenient and efficient.

Paper money facilitated trade and commodity exchange. Its advantages of portability, easy storage, and easy exchange made commodity transactions more convenient and efficient, promoting the development of the commodity economy.

The introduction of paper money also served political and military needs. During times of war, a significant amount of military expenditure was required. Paper money allowed for the rapid mobilization of funds, which was beneficial for achieving military victories.

In conclusion, paper money played a crucial role in ancient China. Its emergence facilitated the development of the commodity economy, solved the problem of insufficient copper coins, facilitated trade and commodity exchange, and also served political and military needs.

ancient Chinese paper money significance in china

The appearance of silver notes (银票) in the history of currency was a significant advancement. Some experts in the field argue that the origin of Chinese silver notes can be traced back to the “White Deer Skin Money” during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty and the “Flying Money” of Emperor Xianzong in the Tang Dynasty. During Emperor Wu’s reign, due to prolonged warfare with the Xiongnu, the national treasury was depleted. To address financial difficulties, in addition to minting “Three Zhu Coins” and “White Gold Coins” (an alloy of silver and tin), the government also issued “White Deer Skin Money.” This money was made from white deer skins, measuring one square foot, with colorful decorations on the edges, and each piece was fixed at a value of 400,000 coins. As its value greatly exceeded the intrinsic worth of the deer skins, “White Deer Skin Money” was only used as gifts between nobles and was not employed for general circulation. Therefore, it can be considered a precursor to silver notes but not a genuine form of silver notes.

“Flying Money” appeared during the mid-Tang Dynasty. At that time, carrying a large quantity of copper coins was inconvenient for merchants traveling for business. Hence, they first obtained a voucher from the government that recorded the amount of money they carried, which they could then use to withdraw funds or make purchases in a different location. This voucher was called “Flying Money.” However, “Flying Money” was essentially a form of exchange business and did not actively circulate as currency, and thus, it was not a true form of silver notes.

The true beginning of silver notes was in Chengdu, Sichuan, during the Northern Song Dynasty. Its emergence was not accidental but rather an inevitable result of the social, political, and economic development at the time. The rapid growth of the commodity economy during the Song Dynasty increased the demand for currency in trade. However, there was a shortage of copper coins, which could not meet the increasing circulation needs. In the Sichuan region, iron coins were in use, but their low value and heavy weight made them highly inconvenient. For example, one copper coin was equivalent to ten iron coins, with a weight of 25 catties for large coins and 13 catties for medium coins. Purchasing a piece of cloth required 20,000 iron coins, weighing approximately 500 catties, necessitating transportation by carts. Consequently, there was an objective need for a more lightweight currency, which was one of the main reasons for the early appearance of silver notes in Sichuan.

Moreover, although the Northern Song Dynasty was a highly centralized feudal autocracy, there was no unified national currency. The country had several currency regions, each with its own currency, not mutually interchangeable. There were 13 administrative regions using specialized copper coins, four regions using specialized iron coins, and Shaanxi and Hedong regions using both copper and iron coins. Each currency region strictly prohibited the outflow of its own currency, making silver notes an effective measure to prevent the outflow of copper and iron coins.

Furthermore, the Song Dynasty government was frequently attacked by the Liao, Xia, and Jin Dynasties, incurring significant military and reparations expenses. Issuing silver notes was necessary to compensate for financial deficits. These various reasons led to the creation of silver notes. The appearance of silver notes facilitated commercial transactions, offset the shortage of metallic currency, and represented a significant achievement in the history of Chinese currency. Additionally, as the earliest form of silver notes issued in China and the world, silver notes also hold a crucial position in the history of printing and engraving, playing an essential role in the study of ancient Chinese silver note printing technology.

ancient Chinese paper money VS Ghost money

Ancient Chinese paper money and “Mingbi” (also known as “ghost money” or “spirit money”) are significantly different in nature, purpose, and historical context.