China, with its rich history and diverse cultural heritage, boasts an impressive number of palaces that are scattered across the vast expanse of the country. These magnificent structures reflect the architectural prowess, royal splendor, and dynastic legacy of China. From the iconic Forbidden City in Beijing to lesser-known palaces in different regions, the country is home to a remarkable array of imperial residences. In this article, we will explore the number and significance of palaces in China, offering a glimpse into the grandeur of its imperial past.

what are Chinese palaces called?

Here is the translation of the titles for ancient palaces in Chinese:

大内 (dà nèi) – The Inner Palace: Refers to the emperor’s palace or the treasury within the palace.

玉阙 (yù què) – The Jade Gate: Refers to the imperial palace or the imperial court.

星闱 (xīng wéi) – The Star Court: Refers to the imperial palace or the imperial court.

紫垣 (zǐ yuán) – The Purple Wall: Figuratively refers to the imperial palace.

皇城 (huáng chéng) – The Imperial City: Refers to the imperial palace.

金銮殿 (jīn luán diàn) – The Hall of Golden Chimes: Symbolically refers to the imperial palace.

金殿 (jīn diàn) – The Golden Hall: Refers to the palace within the imperial palace.

宫阙 (gōng què) – The Palace Gate: Refers to the palace or the imperial palace.

what is Chinese palace made of?

Ancient palaces in China used a wide range of materials for construction, including stone, wood, bricks, tiles, and clay. Let’s provide a detailed introduction to these materials:

· Stone:

Stone was one of the most commonly used building materials in ancient Chinese palaces. Different types of stone, such as granite, marble, and sandstone, were used. Granite, in particular, was widely favored due to its hardness, durability, and resistance to weathering.

Advantages of stone include high durability, with the ability to remain unchanged for hundreds or even thousands of years. However, stone is costly, requires complex craftsmanship, and is difficult to process, making it less suitable for intricate decorative details. Stone is primarily used for constructing large architectural components like columns and door frames, as well as for walls and foundations.

· Wood:

Wood was another prevalent material in ancient palace construction. Common types of wood used included pine, cypress, and locust, with pine being the most commonly employed. Pine wood is valued for its low density, high strength, and resistance to decay, making it an ideal building material. Common wooden components in ancient palaces include beams, columns, and tenons.

· Bricks and Tiles:

Bricks and tiles played a significant role in ancient palace architecture. A variety of bricks and tiles were used, including blue bricks, yellow bricks, and interlocking tiles.

Blue bricks are known for their strong fire resistance and durability, making them suitable for constructing gates, city walls, and other structures. Yellow bricks, with their fine texture and aesthetic appeal, were widely used for palace exteriors and roofs. Interlocking tiles, composed of two layers of tiles with a layer of clay in between, provided insulation and were extensively used in ancient palace construction.

· Clay:

Clay was a common material used in the construction of walls and foundations in ancient palaces. Ancient China employed various types of clay, including loess, clay, and lime.

Loess, due to its solid texture and strong resistance to weathering, was commonly used in wall and foundation construction. Clay, with its pliability and ease of processing, was widely used for manufacturing tiles, clay sculptures, and other crafts. Lime was primarily used for making plaster to cover walls and floors.

· Gypsum:

Gypsum was a commonly used decorative material in ancient palace architecture. It is known for its ease of processing, fine texture, and suitability for carving and ornamentation.

Gypsum allowed for intricate and exquisite carvings and decorations, making it well-suited for detailing in palaces. However, it has lower strength and is fragile, requiring regular maintenance and repairs. Gypsum is commonly used for decorative elements such as floral motifs and reliefs.

what is Chinese palace used for?

A palace is a grand and magnificent architectural structure where emperors handle state affairs and reside. Palaces serve as the locations for imperial gatherings, residing, and are characterized by their vast scale, majestic appearance, and meticulous layout. They evoke a strong spiritual inspiration and exude the dignity of royal authority. In traditional Chinese culture, emphasis is placed on solidifying the earthly order, and unlike Western and Islamic architecture that primarily focuses on religious buildings, palaces represent the highest achievements and largest scale in Chinese architecture. From primitive society to the Western Zhou dynasty, the emergence of palaces went through a phase of chaotic integration, where the leader’s residence, assembly, and sacrificial functions were combined. Eventually, the functions of palaces separated from sacrificial purposes and were exclusively used for royal gatherings and residences. Palaces often exist within a city, relying on a symmetrical and orderly urban layout to highlight their significance within the capital.

what is ancient Chinese palace interior?

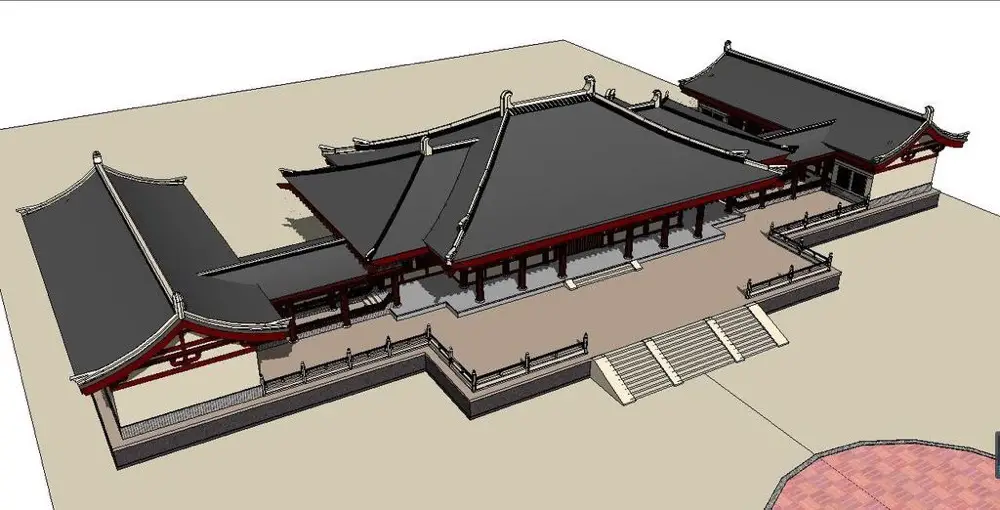

The ancient palaces in China, as commemorative architectural structures, do not primarily focus on luxury but excel in spatial layout of groupings. They possess distinct characteristics and creativity in site selection, adapting to the environment, and handling of space, scale, and color. Since the Shang and Zhou dynasties, imperial palaces have been divided into two main sections: the front court for handling political affairs and the rear court for living and residence. The front court consists of several courtyards centered around the main hall. However, during the Han, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties, side halls were added to the left and right sides of the main hall, serving as spaces for daily court meetings and banquets. The layout evolved during the Sui Dynasty when Emperor Yang of Sui built the Daxing Palace in adherence to the Zhou ritual system. The palace was arranged vertically, incorporating the concept of “three courts”: Guangyang Gate (later renamed Chengtian Gate) served as the grand court for ceremonies on New Year’s Day, Winter Solstice, and tributes from foreign countries; Daxing Hall (later renamed Taiji Hall) became a leisure space during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang, and Zhonghua Hall (later renamed Liangyi Hall) served as the daily court for governance.

The term “interior” in traditional architecture refers to the decoration of palace rooms (referred to as “xiaomu” in the Song Dynasty). Unlike the lavish interiors of Western architecture, Chinese interior design focuses on exquisite craftsmanship and artistic charm. However, similar to Western architecture, there are also many decorative themes influenced by religion. For example, lattice windows come in various shapes such as square, circular, hexagonal, octagonal, and fan-shaped, constructed with tiles, thin bricks, wooden slats, and plaster to form geometric patterns or depict images of animals and plants. The book “The Story of the Western Wing” and the “Garden Treatise” from the Chongzhen era recorded 16 different styles of lattice windows. During the Qing Dynasty, iron plates, wires, and bamboo strips were used to create complex and beautiful patterns. There were over a thousand patterns in Suzhou alone, including fish scales, inscriptions, ingots, and wave patterns. Another example is the decorative painting on the wooden components of official-style architecture, such as columns and brackets, which have been adorned with colorful paintings since the Warring States period. Common motifs include clouds, immortals, plants, and animals. During the Six Dynasties, lotus petals were frequently used. There are also coffered ceilings, as mentioned in the Song Dynasty’s “Construction Methods” and the Liao Dynasty’s architecture, where eight intersecting arches support the ceiling, surrounded by “heavenly palace towers” (wooden carvings of halls, pavilions, towers, and corridors representing the residences of immortals and Buddhas).

Metals, particularly copper, were widely used for architectural decoration. Copper has a beautiful color, is easy to work with, and is resistant to rust, making it suitable for embellishments on wooden structures. In the Ming Dynasty, some buildings were entirely constructed with copper, known as “Jin Dian” or “Golden Halls.” Precious metals such as gold and silver were used for painted or inlaid components. “Fengsu Tongyi” recorded that even though Emperor Wen of Han was frugal, the front hall of the Pre-Yong Palace was extravagant, adorned with colorful carvings and painted beams. Precious gems, jade, shells, and embroidered fabrics were also embedded in the building frames. However, after the Song Dynasty, these materials were gradually replaced by painted decorations.

During the Ming Dynasty, furniture featured rounded or elliptical sections instead of rectangular ones, with precise and delicate joinery. The design focused on human use, emphasizing a beautiful and elegant appearance while avoiding excessive decoration. The artistic value of Ming furniture is extremely high.

what is ancient Chinese palace layout?

The layout characteristics of ancient Chinese palace architecture include:

Central Axis Symmetry: Ancient Chinese palaces were laid out in strict central axis symmetry. The palaces themselves were divided into two parts: the “front court” and the “rear residence.” The front court was where the emperor conducted political affairs and held grand ceremonies, while the rear residence was where the emperor and his consorts lived.

Front Court and Rear Residence: This principle was established during the Zhou Dynasty and has been followed ever since. The front court, known as the “court for political affairs,” and the rear residence, known as the “residence for living,” form the basic layout of palaces throughout history.

Three Halls and Five Gates: Ancient texts referred to palaces as the “nine-tiered palace of the emperor’s family,” and this system of multiple gates and halls was established in the early Zhou Dynasty. The “Five Gates” of the Forbidden City in Beijing are the Gate of Supreme Harmony, the Gate of Heavenly Purity, the Gate of Heavenly Purity (also called the Meridian Gate), the Gate of Noon, and the Gate of Great Harmony. The “Three Halls” refer to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Central Harmony, and the Hall of Preserving Harmony.

The layout of the three halls and five gates has been followed by subsequent emperors in accordance with ceremonial requirements, but there have been changes and developments in architectural form based on practical needs. This palace layout is not only majestic and impressive, but also a symbol and embodiment of the hierarchical and orderly spirit of ancient Chinese feudal society.

Left Ancestral Temple, Right Altar of the Earth: According to the record in the Book of Rites, when establishing the ancestral temple and altar of the earth for the founding gods, it is stated, “The ancestral temple is on the left, and the altar of the earth is on the right.” When constructing imperial palaces, this principle of left ancestral temple and right altar of the earth is generally followed. The location of the ancestral temple should be in the eastern or southeastern part of the entire royal city, while the altar of the earth is located in the western or southwestern part. This practice has been passed down through the generations.

The furnishings of Chinese palaces

Huabiao (Decorative Columns)

Huabiao is usually made of stone and serves as a decorative column in palace architecture.

Stone Lions

Stone lions have the role of warding off evil spirits and symbolizing “nobility and dignity.” They are often placed in pairs, with the male lion on the left and the female lion on the right.

Jialiang and Sundial

Jialiang is an ancient standard measuring tool, which includes units such as hu, dou, sheng, he, and yue. It represents the unified and prosperous nation. Sundial, also known as a sun clock, indicates time based on the position of the shadow cast by a pointer.

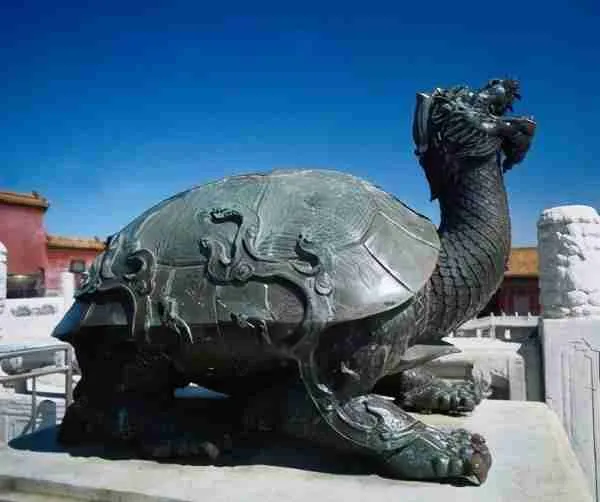

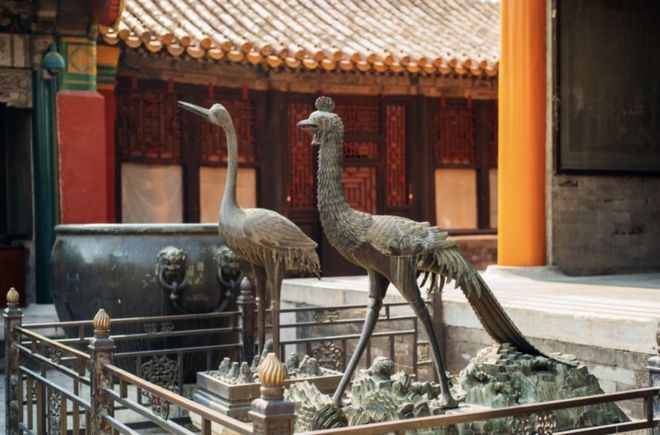

Bronze Turtles and Bronze Cranes

Bronze turtles and bronze cranes are often placed in front of palaces, symbolizing the longevity and prosperity of the monarch.

Jixiang Gang (Auspicious Water Jar)

Jixiang Gang is placed in front of the palace to prevent fires. In ancient times, it was called “Men Hai,” implying that the water in the jar is as vast as the sea.

Ding-style Incense Burner

The incense burner is a ceremonial vessel used to hold burning incense and pine branches during grand ceremonies.

Why did ancient China build palaces?

Symbol of Power: Ancient emperors were the highest rulers of the country and needed a residence that represented the center of power. Therefore, ancient palaces were often the largest, located in the central part of the city, and extremely grand and luxurious. The architectural structure, number of rooms, and decoration were all determined by explicit hierarchical rules, varying for the emperor, feudal lords, and officials.

Symbol of Wealth: With the emergence of private ownership in ancient times, emperors were expected to enjoy the most luxurious and high-ranking residences, representing their control over the wealth of the nation.

Yin-Yang and Five Elements Theory: The ancient belief in the theory of yin and yang and the five elements influenced palace construction. Emperors believed in the concept of qi (energy) and saw imperial tombs as yin dwellings and palaces as yang dwellings, aligning with the flow of qi. Palaces were built in a magnificent and grand style, reflecting the supreme power enjoyed by emperors in both life and death.

Personal Preferences and Daily Needs: The construction and expansion of ancient palaces often occurred during the founding or prosperous periods of dynasties. Emperors during such times often had a strong desire to showcase their achievements and satisfy their expansion ambitions. Additionally, the presence of numerous family members, consorts, and palace staff, with different classifications and areas, required large-scale housing to accommodate them. The saying goes, “A big family requires a big house.”

Political System Beliefs and Representation: The emperor, as the highest ruler of the country and the mythical figure of the Son of Heaven, represented a position of supreme authority, with a sense of mystery and aloofness. The palace served as the political center of the nation and was located in the heart of the capital city, featuring symmetrical design with the city built around it. The palace symbolized dignity, status, and international image, especially in Chinese architecture, which often emphasized grandeur and the characteristics of ruling power.

Regarding palaces, the Shuowen Jiezi dictionary states, “Palaces are the tallest and grandest buildings.” In the Yueyang Tower by Fan Zhongyan, it is mentioned, “Living in a high palace, one should worry about the people.” The term “palace” refers to the emperor’s residence.

According to legends, the ancient rulers Yao, Tang, and Zhou had their own palaces. Although it may sound glorious, some of these palaces were nothing more than mud and thatch, with higher-end ones being made of wood. They were merely embellishments of the grandeur of Yao’s platform.

The rapid development of palace architecture occurred during the Qin Dynasty established by Emperor Qin Shi Huang after unifying the six states. While inheriting the cultural influence of the Zhou Dynasty, the Qin Dynasty’s architectural style, influenced by the exoticism of the Western Regions, emphasized largeness. Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s palaces, such as the Xianyang Palace and the Palace of the Perishing Consort, were unprecedented monumental structures that fully embodied the spirit of imperial power.

Why are Chinese palaces and temples the same?

The residences of emperors shaped the form of palaces as symbols of imperial power, while temples served as the dwellings of spiritual leaders, representing the symbol of spiritual authority. Therefore, they were recognized by successive emperors as having the same luxurious living conditions as imperial palaces. Buddhism had a significant influence on ancient architecture. The period after the Sui and Tang dynasties marked the pinnacle of Buddhist architectural development and the beginning of showcasing distinctive Chinese architectural features. As Buddhism matured, it established a relatively comprehensive and systematic management system. With political unification, rapid economic and cultural development, and a flourishing society, it created favorable conditions for the spread and development of Buddhist culture. Buddhism gave rise to various sects such as Esoteric Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, and Huayan Buddhism. The integration and fusion of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism brought about significant changes in Buddhist architecture.

Buddhist architecture reflected the ruling ideology of ancient China, gradually forming an architectural concept based on ancient Chinese palaces. Traditional Buddhist architecture, with the stupa as its central element, started to continuously integrate with Buddhist religious art and ethnic traditional customs. This led to the continuous development of Sinicized Buddhist architectural art, greatly influencing ancient Chinese architectural culture.

Did ancient Chinese emperors live in palaces?

Most emperors, once they ascended to the throne, would remain inside the palace or stay within the capital city. They were not allowed to venture outside as per regulations, and the cost of doing so was extremely high. However, emperors occasionally left the palace for various reasons, including the following:

Imperial Inspection and Tours: Emperors would undertake tours to inspect their realm, perform sacrificial rites, or embark on military campaigns. Examples include Qin Shi Huang’s famous tour of the country and the six southern tours of Kangxi Emperor and Qianlong Emperor.

Sacrificial Rites: Emperors would participate in rituals such as the Winter Solstice Ceremony to worship the heavens or visit imperial tombs to pay respects to their ancestors.

Military Campaigns: Emperors would personally lead expeditions and engage in warfare. One legendary example is the “Imperial Journey to Battle” where Ming Chengzu (Emperor Yongle) led military expeditions to the northern frontier.

Garden Excursions: Emperors would frequently engage in leisurely activities, such as visiting gardens like the Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace) and the Mountain Resort in Chengde.

Of course, there were instances in ancient times when emperors did not reside in the palace. For example, during the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Zhengde preferred to live in the Leopard Room outside the palace, while some emperors of the Qing Dynasty preferred to reside in the Yuanmingyuan, which, strictly speaking, was the imperial garden of the Qing emperors.

Leopard Room:

According to scholars’ research, the Leopard Room of the Ming Dynasty was located in the area of today’s Zhonghai and Nanhai in Beijing, which was referred to as “Taiye Pool” during the Ming Dynasty. This was a place that the emperor himself often visited. Due to Emperor Zhengde’s love for entertainment, he constructed the Leopard Room here, where he housed various exotic animals and rare birds. To feed the animals in the Leopard Room, Emperor Zhengde ordered the construction of “deer fields” and “pigeon houses” around the Leopard Room. Every day, he would personally come to the Leopard Room to observe the scenes of ferocious beasts hunting for prey. If he was pleased, he would generously reward the eunuchs serving by his side. Gradually, within Beijing’s imperial city, a large number of “animal-keeping rooms” such as the Elephant Room, Falcon Room, Tiger City, Leopard Room, and Pigeon House were established. Later, Emperor Zhengde even abducted many beautiful women from the common people and enjoyed himself with them in the Leopard Room until he tragically drowned at the age of 31.

Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace):

According to historical records, during the Qing Dynasty, emperors Yongzheng, Qianlong, Jiaqing, Daoguang, and Xianfeng spent more time each year in the Yuanmingyuan than in the Forbidden City. Emperor Xianfeng and Emperor Daoguang, in particular, would spend over 200 days per year residing in the Yuanmingyuan. The shortest stay by Emperor Daoguang in the Yuanmingyuan was 201 days. From this, we can see that these emperors had a special attachment to the Yuanmingyuan. Both Kangxi Emperor and Yongzheng Emperor passed away while staying in the Yuanmingyuan.

how to prevent fire in Chinese palaces?

As the residence of the emperor himself, ancient imperial palaces were most vigilant about the threat of fires, in addition to guarding against rebellions. As early as the ancient Zhou Dynasty, a specific fire alarm system was established, and certain periods of the year were designated as completely fire-free, which later became known as the “Cold Food” tradition commemorating Boyi and Shuqi.

Throughout history, central governments had dedicated fire brigades responsible for the capital. In the Han Dynasty, the “Golden Bird Guards,” responsible for maintaining law and order in Chang’an, also had the duty of fire prevention. The Tang Dynasty had a specialized firefighting unit called the “Wuhou Workshop.” The later Song Dynasty had a firefighting unit called the “Water Patrol,” which grew to a scale of several thousand people. The Ming and Qing dynasties also established professional firefighting units with specialized skills. However, despite these strict precautions, imperial residences of past emperors would still occasionally be damaged by fires, and sometimes even the entire palace would be reduced to ruins.

In fact, if it weren’t for times of war, the damage suffered by the palaces of the Qin and Han dynasties was usually not significant. Compared to later dynasties, the population density and distribution of buildings in the capitals of the Qin and Han dynasties were relatively low, with large open spaces between buildings that served as firebreaks. However, fire alarms would still occasionally sound in Chang’an, Luoyang, or other palace complexes. For example, during the reign of Emperor Shun of Han, the palace in Luoyang caught fire, resulting in the destruction of valuable items and treasures. During the reign of Emperor Zhang of Han, a fire broke out in the residence of Princess Xinping, spreading to the western pavilion of the imperial palace. In the waning years of Emperor Huan of Han, the imperial palace experienced as many as 11 fires.

The Tang Dynasty was not an era characterized by frequent palace fires. This was because the climate between the 7th and 9th centuries was mild, with abundant rainfall, and the capital’s residential areas were strictly divided into blocks. The implemented system of blocks and markets left enough space between residential and commercial areas, and arbitrary movement was strictly prohibited. While this restricted the freedom of the city’s residents, it also reduced the frequency of fires. However, in the Song and Ming dynasties, when the block and market system was broken and the population density in the capital increased, fires finally became the greatest threat to the imperial palaces.

The most famous palace fire in the Song Dynasty occurred in 1032. After the completion of the Wendeng Hall, a massive fire suddenly broke out in the imperial palace, quickly spreading to major buildings such as the Chongde Hall, Changchun Hall, and Huiqing Hall, eventually reducing the main halls of the palace to ashes.

This was an unprecedented disaster in history, and Emperor Renzong of Song ordered an investigation into the cause of the fire. It was eventually determined that a palace seamstress, who was responsible for sewing, had accidentally caused the accident while using a fire pot. A fire pot was similar to a modern iron, but in the absence of electricity, it required placing hot coals inside to generate heat.

However, the officials and ministers of the Song Dynasty evidently had not yet learned to attribute all the responsibility to temporary workers. After identifying the direct culprit, the magistrate of Kaifeng pointed out the true cause of the fire: the high population density in the harem, the cramped living spaces, and the proximity of stoves to wooden components such as beams. The long-term heat generated from cooking created a significant hazard by drying out the wood.

During the Ming Dynasty, the Fire God seemed to have no mercy for the Zhu family. Once, Emperor Chengzu ordered the release of fireworks in front of the Wumen Gate to celebrate the New Year, but it accidentally ignited the gate tower. The fire raged on, even burning to death the highest-ranking official in charge of commanding the firefighting efforts, eventually completely destroying the Wumen Gate.

Realizing the enormous losses suffered by the imperial palaces during the Ming Dynasty, the Qing Dynasty made thorough renovations to the Forbidden City. Firstly, they added brick and stone walls between buildings to prevent the spread of fires among wooden structures. Secondly, they introduced a new firefighting tool called the “water dragon” from Japan, an efficient device used for indoor firefighting. Thirdly, they installed numerous water tanks throughout the palace and ordered strict patrols to identify any hidden fire hazards.

During the Qing Dynasty, there were no catastrophic events like the complete destruction of the three main halls. However, incidents of fire in the Forbidden City still occurred from time to time, and even the Yongle Encyclopedia, which had narrowly escaped destruction in the burning of the three main halls, was lost in a fire in the Qianqing Palace.

how did ancient palaces spend cold winters in China?

The earliest method of heating and keeping warm in houses was the use of fire pits. Based on excavations at sites such as Banpo and Jiangzhai, the hearth located near the entrance of primitive houses served not only for cooking but also provided some warmth.

This design allowed it to absorb the air blown into the house from outside, aiding in combustion, while also blocking the cold wind from entering the house during the winter.

The fireplace used in the Qin Dynasty’s imperial palace combined the advantages of fire pits and fire pots, overcoming their shortcomings.

During the Han Dynasty, the official halls where the emperor resided in winter for warmth were called “warm chambers.” These chambers were equipped with various devices for protection against the cold.

Among them, pepper was the main item used for winter heating. Pepper mixed with clay was applied to the walls, which were adorned with brocade, while woolen blankets were spread on the floor.

During the Tang Dynasty, nobles began using ruichan and fengchan for warmth. Ruichan was a tribute brought from the Western Liang Kingdom, so named because it was a hundred feet long and green in color.

It was said that a single ruichan could burn for about ten days and emitted intense heat that made it unbearable to approach.

Fengchan, on the other hand, was shaped like a pair of phoenixes made by molding charcoal dust with honey. During winter, they were placed in stoves, with sandalwood spread under the stove to keep their ashes separate.

In the Ming and Qing dynasties, Beijing experienced about 150 days of cold weather in a year. During the coldest times, temperatures could drop to as low as minus twenty to thirty degrees Celsius, with water freezing into ice.

How to keep warm in the cold winter was an issue that could not be ignored in the imperial palace at that time.

Architects at the time made great efforts in the palace’s structure to address the heating problem. They constructed the outer walls of the palace with hollow double walls, and passages were dug below the walls, creating flues. The openings for adding charcoal were located under the eaves outside the halls.

When heating was needed, wood charcoal was burned in the openings, allowing the hot air to be supplied to the entire hall through the hollow walls. Additionally, to ensure smooth circulation of the hot air, there were vents at the end of the flues, allowing the smoke to be released through the vents so that people in the halls would not smell the pungent odor of charcoal.

To ensure the smooth passage of warmth to the people in the palace, the flues were generally directed to the heated beds in the bedrooms and various chambers, creating warm beds or warm chambers, making the Forbidden City warm even in winter.

In addition to the warm chambers in the palace, there were also warm beds in each living quarter. These beds had flues beneath them, similar in structure to the kang beds found in present-day northern rural areas.

There were indoor fire stoves and foot stoves placed near the feet for warming. Additionally, there were hand stoves, exquisitely designed and portable. The fuel for these stoves was charcoal.

Due to the large amount of charcoal consumed during winter, a specialized agency was established in the palace to manage the winter heating supplies and related matters. For example, during the Ming and Qing dynasties, there was the Ministry of Cherishing Firewood, which was responsible for supplying firewood and charcoal to the palace. The name of the ministry implied the importance of cherishing the charcoal and avoiding waste.

Under the Ministry of Cherishing Firewood, there were three specialized divisions with specific responsibilities. The first was the Department of Fire Installation, which was in charge of installing fire stoves and transporting firewood and charcoal. It was led by two chief eunuchs and had fifty subordinate eunuchs. The second was the Department of Firewood and Charcoal, responsible for storing and distributing firewood and charcoal. It also had two chief eunuchs and twenty-five subordinate eunuchs. The third was the Department of Kang Stoves, which specifically handled the ignition of the heated beds. It was led by two chief eunuchs and had twenty-five eunuchs.

All of these tasks were not easy. Just considering the distribution of charcoal, with so many people in the palace and varying standards based on rank, the daily coal demand in the palace differed. Moreover, the charcoal provided to members of the imperial family had to be powerful, smokeless, and odorless.

The charcoal used in the Qing Dynasty’s imperial palace was mostly produced from high-quality wood burned in places like Tongzhou, Zhuozhou, Daxing, and Yizhou. Afterward, it was cut into small pieces, packed in baskets, and transported into the palace for storage.

Since the charcoal was processed in the Red Weaving Field, it was called “Hongluo Charcoal.”

In addition, the design of the palaces where the emperor and empress resided showcased exceptional craftsmanship. The orientations of these palaces were all south-facing, while the front eaves were set at a 45-degree angle to the winter sun, allowing direct sunlight into the palaces.

With the continuous development of technology and increasing diplomatic ties with various countries, heating devices in the Qing palace reached a certain level of sophistication.

During the Kangxi era (1662-1722), glass was introduced to the court and installed in the palace’s windows, replacing traditional paper windows. This not only enhanced aesthetics and transparency but also eliminated the draft issues associated with paper windows, making the palace interior warmer.

During the Xuantong era (1909-1911), even more advanced heating facilities, such as electric heaters, were installed in the palaces where Empress Dowager Longyu resided.

Although the Forbidden City was an imperial palace, the emperor actually spent only a few months there each year. Most of the time, he resided in the Chengde Mountain Resort for summer or in the Yuanmingyuan for winter.

how to avoid summer in ancient Chinese palaces?

Although ancient emperors did not have air conditioning, they still found ways to stay comfortable during the summer. Here are a few examples:

Using ice blocks for cooling: Ice blocks were commonly used in ancient times to cool down the imperial palace during hot weather. During the Tang Dynasty, craftsmen in Chang’an City were responsible for transporting ice blocks to the palace. These blocks were usually cut during the winter and stored in deep underground cellars. When summer arrived, they were brought up and used to cool down the palace. However, ice blocks were precious and not everyone in the palace had access to them. Only the emperor, empress, and favored concubines could enjoy such a luxury, while eunuchs and palace maids had to endure the heat.

Palace maids fanning: In many historical dramas, you may have noticed that there were palace maids standing beside the emperor, holding fans. These fans served as decorations but also helped cool down the emperor during the summer.

Summer retreats: It was a common practice for many Qing Dynasty emperors to go on summer vacations and retreats to avoid the heat. One popular destination was the Chengde Mountain Resort. This practice was also observed during the Tang and Song Dynasties. For example, during the Tang Dynasty, the emperor often sought refuge in a place called Ganquan Palace, located on the outskirts of Chang’an City. Similarly, during the Ming Dynasty, the emperors rarely left the capital but built the Imperial Summer Palace, called Ying Tai, in Beijing. It was surrounded by water and served as a summer retreat for the emperor and his consorts.

Cool architecture: In the Tang Dynasty, there were special palaces for cooling called “Hanzhong Palace.” These palaces were built near water and were equipped with mechanical cooling systems. These systems used circulating cold water and fans to blow the cool air into the palace. They also directed the cold water to the roof, creating artificial water curtains that generated coolness.

In addition, there were other architectural features designed to provide relief from the heat. For example, during the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, people would build “liangpeng” (cooling pavilions) in Beijing. These pavilions were constructed using bamboo frames and covered with mats as a roof. They were erected in courtyards or attached to the eaves, providing shade and preventing direct sunlight from hitting the walls. This helped keep the exterior walls cooler and prevented the ground in the courtyards from heating up quickly.

To ensure sufficient lighting, the ancient Chinese also invented movable roofs. They cut the mats into rectangular pieces and attached long ropes to the edges. When the sunlight was strongest, the mats were completely covering the roof. But in the morning or evening, the ropes could be gently pulled to automatically open the mats, allowing light and cool breeze to enter.

Examples of such cooling structures can be seen in the Taiye Pool, also known as the Penglai Pool, in the Daming Palace during the Tang Dynasty. It was the most important royal garden in the palace and was located in the central area. The Hanzhong Palace, situated on the southern bank of the Taiye Pool, was built near water to provide a cool and pleasant environment during the summer.

In summary, ancient emperors employed various methods to beat the heat during summer, including using ice blocks, relying on palace maids with fans, going on summer retreats, and constructing cool architecture with innovative cooling systems.

Do palaces symbolize in ancient China?

Palaces in ancient China held significant symbolism and represented various aspects of power, authority, and the imperial system. Here are some of the symbolic meanings associated with palaces in ancient China:

Imperial Power: Palaces were the residence of the emperor, the supreme ruler of China. They symbolized the emperor’s authority, legitimacy, and the centralization of power. The grandeur and opulence of the palaces reflected the emperor’s status as the Son of Heaven and the embodiment of imperial power.

The mandate of Heaven: Palaces represented the divine approval and mandate to rule. Emperors believed that they ruled with the blessing and support of the heavens, and the palace served as a physical manifestation of this celestial authority.

Political Center: Palaces were the political center of the empire, where the emperor conducted state affairs, held court sessions, and received officials and foreign envoys. They symbolized the governance and administrative functions of the imperial system.

Cultural Heritage: Palaces were repositories of Chinese culture and tradition. They housed precious artworks, calligraphy, historical artifacts, and royal libraries. Palaces served as centers for scholarly pursuits, fostering the development and preservation of Chinese culture.

Social Hierarchy: Palaces reflected the hierarchical structure of ancient Chinese society. Different areas within the palace were designated for specific ranks and officials, emphasizing the social order and the emperor’s position at the apex of the social pyramid.

Symbol of Prosperity: Palaces showcased the wealth and prosperity of the empire. Lavish decorations, intricate architecture, and meticulously designed gardens demonstrated the economic strength and achievements of the ruling dynasty.

Security and Protection: Palaces were fortified structures with walls, gates, and guards, symbolizing the protection and defense of the imperial family. They represented stability and the safeguarding of the empire against external threats.

Overall, palaces in ancient China embodied the essence of imperial power, divine authority, political governance, cultural heritage, and societal hierarchy. They served as physical manifestations of the imperial system and its values, while also reflecting the grandeur and richness of Chinese civilization.

famous palace in China (how many palaces are there in China?)

- One of the most famous palaces in China is the Forbidden City, also known as the Palace Museum. Located in the heart of Beijing, it was the imperial palace of the Ming and Qing dynasties and served as the residence of the emperors for over 500 years. The Forbidden City is renowned for its immense size, exquisite architecture, and historical significance. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and attracts millions of visitors each year.

- Another famous palace in China is the Summer Palace, situated in the outskirts of Beijing. It is a vast imperial garden complex that served as a retreat for the emperors during the hot summer months. Known for its stunning lakes, pavilions, and landscaped gardens, the Summer Palace is a masterpiece of Chinese garden design and is also recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- The Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, is another iconic palace in China. It is a monumental structure perched on a hilltop and was the winter residence of the Dalai Lamas, the spiritual leaders of Tibetan Buddhism. With its striking architectural features and rich cultural and religious significance, the Potala Palace is a symbol of Tibetan heritage and attracts numerous pilgrims and tourists.

- The Chengde Mountain Resort, located in Chengde, Hebei Province, is a vast imperial complex that served as the summer retreat for the Qing emperors. It encompasses a combination of palaces, gardens, and temples spread over a large area. The Chengde Mountain Resort is renowned for its blend of Chinese and Tibetan architectural styles and its scenic landscapes.

- Additionally, the Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, is another notable palace in China. It was the early capital of the Qing Dynasty and houses a complex of palaces, halls, and gardens. The Shenyang Imperial Palace showcases the architectural and cultural heritage of the Manchu rulers and is a popular historical site.

These are just a few examples of the famous palaces in China, each with its unique historical, architectural, and cultural significance.

palaces in Chinese history

Palace architecture has played a significant role in the development of Chinese architecture throughout history. The imperial palace, representing the core and symbol of each dynasty, holds great importance. Examples of famous palaces in Chinese history include:

- Xianyang Palace and Afang Palace of the Qin Dynasty.

- Weiyang Palace and Changle Palace of the Han Dynasty.

- Taiji Palace and Daming Palace of the Tang Dynasty.

- The Forbidden City (also known as the Palace Museum) of the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

The emergence of palace architecture can be attributed to social class differentiation. Even in primitive tribes during the late Neolithic period, there were variations in building scale, with a central large house surrounded by smaller houses in a circular arrangement. The largest house was reserved for the tribe’s ruler, which became the prototype for palace architecture.

During the “Maoci and Tujie” stage, elevated platforms made of compacted earth were used to support houses, and thatched roofs made of reeds were constructed on top. Examples of this stage include the Erlitou site in Yanshi, Henan Province, the Panlongcheng site in Huangpi, Hubei Province, and the Yin ruins in Anyang, Henan Province.

The introduction of tiles marked a significant development in palace architecture. Evidence of the use of tiles has been found in the early Western Zhou Dynasty palaces. By the Spring and Autumn period, tiles became more widely used.

The use of elevated platforms in palace architecture served to prevent dampness and increase structural stability. During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, various feudal states constructed numerous palaces on high platforms, which were several meters to over 10 meters high. The decoration and color of palace architecture further developed during this period.

The Wenyang Palace of the Han Dynasty was the first palace complex and one of the largest in Chinese history. It covered an area of approximately 5 square kilometers, featuring pavilions, halls, ponds, and gardens.

The architectural layout of Wenyang Palace had a profound influence on subsequent palace architecture, forming the foundation for the layout of palace cities for over 2,000 years. It continued to be used as the central hall for governance by multiple dynasties, including Xinmang, Western Jin, Former Zhao, Former Qin, Later Qin, Western Wei, and Northern Zhou. It is the most extensively used and longest-lasting palace complex in Chinese history.

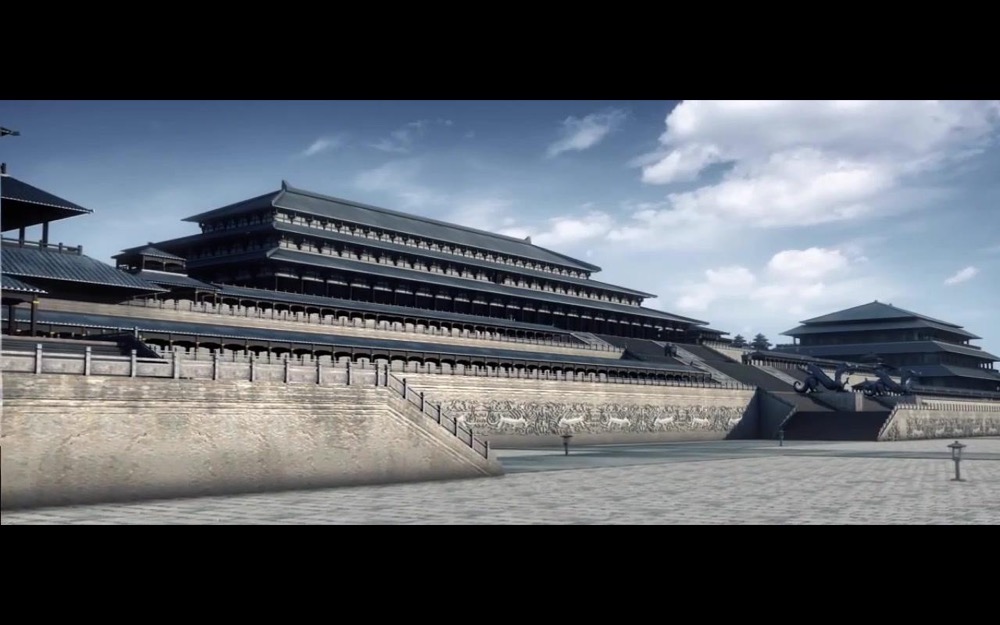

During the Tang Dynasty, palace architecture reached a prosperous stage. The Great Ming Palace, known as the Daming Palace, was the political center of the prosperous Tang Dynasty. It covered a vast area and had over 40 halls. The architectural style and layout of the Daming Palace had a direct influence on later palace architecture, even into the Qing Dynasty.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties are best represented by the Forbidden City in Beijing. Covering an area of 720,000 square meters, it is one of the world’s largest and most well-preserved wooden architectural complexes. The Forbidden City is divided into the Outer Court and Inner Court. The Outer Court consists of the three main halls—Hall of Supreme Harmony, Hall of Central Harmony, and Hall of Preserving Harmony—where grand ceremonies were held. The Inner Court consists of the Palace of Heavenly Purity, Hall of Union, and Palace of Earthly Tranquility. The layout of the palace complex follows strict feudal ceremonial regulations, reflecting the authority of the emperors.

These palaces exemplify the architectural achievements and cultural heritage of different dynasties throughout Chinese history.

first palaces in China

In May 2020, the “Heluo Ancient State,” dating back approximately 5,300 years, was discovered at the Shuanghuaishu Site in Gongyi, China. This discovery filled a crucial gap in our understanding of the key period and region of origin of Chinese civilization and has been hailed by experts and scholars as the “embryo of early Chinese civilization.” Through continuous archaeological excavations, the “Heluo Ancient State” has revealed a newly discovered 4,300-square-meter rammed earth architectural complex and a large-scale courtyard layout. It exhibits the characteristics of early palace architecture in China, pioneering the form of large-scale palace-style buildings and can be regarded as one of the earliest “palaces” in China.

The spatial organization of the large-scale courtyard and the layout of the palace city in the earliest palace discovered in the “Heluo Ancient State” have advanced the understanding of Chinese palace architecture by approximately 1,000 years. This palace layout directly influenced the subsequent urban planning of Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, such as Taosi, Erlitou, and Yanshi Shangcheng. According to research, the gate design of this discovered site is fundamentally consistent with the gate remains of later palace buildings like Erlitou Palace Complex and Yanshi Shangcheng Sites. In terms of origins, the palace discovered in the Heluo Ancient State provides strong support for tracing and exploring the origins of the ancient Chinese palace system.

largest Chinese palaces

Xianyang Palace, once the largest palace in the world, had a total area equivalent to a hundred times that of the Han Dynasty’s Chang’an City and over two thousand times that of the Forbidden City.

The magnitude and scale of Xianyang Palace are difficult for people today to imagine. Its general layout was as follows: Palace Number One was located in the original Xianyang Palace City. It extended from Ta’erpo in the west, passed northeast along the Xianyang Plateau, reached the confluence of the Jing and Wei Rivers, and then turned south, crossing the Wei River. The entire area, with Xianyang as the center, encompassed over a hundred subsidiary palaces and had a diameter of more than 80 kilometers. The Xianyang Palace City occupied an area of 3.72 square kilometers.

Xianyang Palace, the imperial palace of the Qin Dynasty, was constructed during the reign of King Zhao of Qin. After Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified the six states and relocated the capital to Xianyang, continuous expansion took place. Towards the end of the Qin Dynasty, Xiang Yu attacked Xianyang, resulting in the city’s partial destruction by fire.

list of palaces in China

Qin – Palace of the Daming. According to historical records, Emperor Qin Shi Huang instructed artisans to replicate the palace styles of each conquered state and rebuild them in Xianyang, incorporating the beautiful women and bells and drums seized from those states. The palaces spread over a distance of over 200 li within and outside of Xianyang, totaling 207 subordinate structures. It is said that the palaces were later burned by Xiang Yu.

Western Han – Changle Palace, Weiyang Palace. After Liu Bang assumed power, he assigned the task of constructing palaces to Xiao He. When Liu Bang saw the grandeur of the palace projects, he became furious and interrogated Xiao He. Xiao He explained the significance of magnificent palaces for an emperor, and upon hearing this, Liu Bang nodded in agreement.

Eastern Han – Southern and Northern Palaces. The Southern and Northern Palaces were located in the south and north of Luoyang, respectively, with a distance of seven li between them and connected by covered passages. In addition to the palaces, there were numerous parks and pavilions outside Luoyang for the emperor’s leisure. The Western Park was the largest, where Emperor Ling of Han indulged in sensual pleasures, including a nude swimming pool to appreciate the beauty of women’s skin. In the Inner Park, he enjoyed riding a donkey-drawn carriage, finding immense joy in it.

Tang – Taiji Palace, Daming Palace, Xingqing Palace. The earliest was the Taiji Palace, recognized as the most formal palace city, and it was in the Xuanwu Gate, the northern gate of the Taiji Hall, where the famous Xuanwu Gate Incident took place. During the An Lushan Rebellion, the Xingqing Palace suffered severe damage and subsequent Tang emperors generally did not reside there. The Daming Palace was originally a summer palace, but due to Emperor Tang Gaozong’s frequent stay there, expansion took place.

Song – Palace buildings in Bianjing and Lin’an. The capital of Northern Song was Bianliang, known today as Kaifeng, which was referred to as Dongjing at the time. The tradition of locating the imperial palace in Bianliang started during the Five Dynasties period. After the downfall of the Northern Song, the Southern Song was established, and the capital was moved to Lin’an, present-day Hangzhou. In the relatively secure Southern Song period, the palace buildings underwent continuous repair and expansion.

Yuan – Palace of Eternal Happiness. The Mongol Empire, which spanned Eurasia, ultimately chose Yanjing (present-day Beijing) as its capital, naming it Dadu. The palace complex was divided into three parts: the Inner Court, the Palace of Eternal Happiness, and the Palace of Rising Sacredness.

Ming and Qing – Forbidden City. It remains well-preserved to this day. In terms of construction techniques and artistic level, the Forbidden City surpasses palaces of previous dynasties, despite its relatively small area. The palace was built by Emperor Zhu Di of the Ming Dynasty, and after the downfall of the Ming Dynasty, the Qing Dynasty continued to use the Forbidden City as the imperial palace until its demise.

famous places in ancient China

Qin Dynasty:

A Fang Palace – It was not completed and was similar to the Daming Palace. It served as a separate palace from the Xianyang Palace and had functions such as summer retreat. It can be compared to the Chengde Mountain Resort.

Xingle Palace – Equivalent to the current Forbidden City, serving as the imperial palace of the Qin Dynasty.

Western Han Dynasty:

Weiyang Palace – Equivalent to the current Forbidden City, where the emperor resided and handled political affairs and court meetings.

Changle Palace – The palace where the empress dowager resided.

Jianzhang Palace – The residence for emperors, empresses, imperial concubines, and imperial princes after Emperor Wu of Han.

Eastern Han Dynasty and Cao Wei:

Nangong in Luoyang – The place where the emperor resided and worked.

Beigong – The residence for the emperor and the imperial family.

Sun Wu (Eastern Wu):

Jianye – Taichu Palace was the first palace built in Jianye by Eastern Wu. It originated from the general’s residence of Sun Ce, the older brother of Sun Quan.

Zhaoming Palace – Another important palace building in Jianye, second only to Taichu Palace.

Western Jin (Luoyang):

Followed the pattern of Eastern Han and Cao Wei.

Eastern Jin (Jiankang):

Jianzhu Hall and Taiji Hall were equivalent to the three major halls of the current Forbidden City.

Sui Dynasty:

Chang’an, also known as Chang’an in the Tang Dynasty.

Tang Dynasty (Chang’an):

Taiji Palace was built in the early Sui Dynasty and was called Daxing Palace in the Sui Dynasty. It was actually a general term for Taiji Palace, Donggong, and Yetting Palace. Taiji Palace is equivalent to the current Taihe Hall in the Forbidden City. The East Palace was the prince’s sleeping palace.

Daming Palace in Chang’an – From Emperor Gaozu of Tang onwards, Tang emperors resided here, and court affairs shifted from Taiji Palace to Daming Palace.

Xingqing Palace in Chang’an – The residence of Emperor Xuanzong and Yang Guifei.

Northern Song (Dongjing):

Dading Hall in Dongjing was the place for grand court meetings, equivalent to the Taihe Hall in the Forbidden City.

Wende Hall was the main venue for imperial political activities.

Zichen Hall was the venue for large-scale events held on festivals.

Chuigong Hall was the place for receiving foreign ministers and hosting banquets.

Jiyin Hall and Xuping Tower were places for selecting scholars, watching dramas, and holding banquets.

Funing Hall and Kunning Hall were the residences of the emperor’s concubines.

Linan Dading Hall in Southern Song

The venue for grand court meetings, equivalent to the Taihe Hall in the Forbidden City.

Chuigong Hall – Regular court buildings.

Houdian – Also known as Yandian, the place where the emperor observes the winter solstice and New Year’s Day.

Yuan Dynasty (Dadu):

Daming Hall was the main court hall for the emperor, equivalent to the three major halls of the Forbidden City or the previous court of the Forbidden City.

Yanchun Ge – The place where the emperor meets ministers and conducts Buddhist ceremonies.

Longfu Palace – The residence of the empress dowager.

Xingsheng Palace – The residence of the crown prince, Eastern Palace in the Yuan Dynasty.

Ming and Qing Dynasties (Imperial Palace in Beijing):

Taihe Hall – During the Ming and Qing dynasties, all 24 emperors held grand ceremonies in Taihe Hall, such as ascending to the throne, royal weddings, enthroning empresses, and issuing orders for military expeditions. Additionally, on festivals like the Longevity Festival, New Year’s Day, and Winter Solstice, the emperor received congratulations from civil and military officials here and hosted banquets for royal family members and ministers. During the early Qing dynasty, the palace also hosted the palace examination for newly qualified scholars.

Zhonghe Hall – This was the place where the emperor rested before proceeding to Taihe Hall for major ceremonies. When the emperor performed personal sacrifices, such as at the Altar of Heaven and the Altar of Earth, he would review the sacrificial texts and inspect seeds and agricultural tools here. When the empress dowager received her honorary title, the emperor would review official documents here. Once the jade tablets were completed, they were respectfully presented in Zhonghe Hall for the emperor’s review, and a solemn ceremony was held to store them.

Baohe Hall – In the Ming dynasty, before major ceremonies, the emperor would change into ceremonial attire here, and it was also the place where the emperor received congratulations during the enthronement of empresses and crown princes. In the Qing dynasty, grand banquets were held here on New Year’s Eve and the fifteenth day of the first lunar month, attended by feudal lords, princes, and high-ranking officials. It was also the venue for banquets honoring the fathers of married officials and officials’ family members, as well as for palace examinations.

Qianqing Palace – Qianqing Palace served as the sleeping quarters for the 14 Ming emperors and the Qing emperors Shunzhi and Kangxi. They resided and handled daily political affairs here. During the Ming dynasty, from Emperor Yongle (Zhu Di) to Emperor Chongzhen (Zhu Youjian), a total of 14 emperors lived in Qianqing Palace. Historical records mention that during the reign of Emperor Jiajing, there were more than ten instances where palace maids attempted to strangle him during his sleep, leading Emperor Shizong to move to the Western Pavilion and avoid returning to Qianqing Palace. The “Moving Palace Incident” involving Consort Li Xuanzhi also occurred in Qianqing Palace. Before the reign of Emperor Kangxi in the Qing dynasty, Qianqing Palace followed the Ming system closely. During the reigns of Emperors Shunzhi and Kangxi, Qianqing Palace was closely associated with political affairs. The emperors studied, reviewed memorials, met officials, received foreign envoys, and held imperial ceremonies and private banquets here.

Yangxin Hall – During the Ming dynasty and the early Qing dynasty, Qianqing Palace served as the emperor’s sleeping quarters. After the death of Emperor Kangxi, his son Yongzheng, as an expression of mourning, did not move into Qianqing Palace and instead lived in Yangxin Hall. Yongzheng Emperor then made Yangxin Hall his sleeping quarters and did not move to Qianqing Palace. Another reason was that when Yongzheng Emperor resided in the modestly furnished Yangxin Hall, he wanted to set an example of frugality for the people. However, over time, the furnishings in Yangxin Hall became increasingly luxurious.

During the late Qing dynasty, there were more than 780 items in the palace. From the reign of Yongzheng to the end of the Qing dynasty, eight emperors lived in Yangxin Hall. Emperors Shunzhi, Qianlong, and Tongzhi died in Yangxin Hall. From Yongzheng to the end of the Qing dynasty, the emperors conducted their daily activities here, including handling political affairs. The front hall of Yangxin Hall housed a throne, an imperial desk, and bookshelves containing records and books on the governance experiences and lessons of previous emperors. The Qing emperors frequently met with ministers here and sometimes received foreign envoys. On the fifty-ninth year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1720), he received the Roman Catholic emissary Carlo Ambrogio Mezzabarba in Yangxin Hall, personally accepting the papal memorial and presenting gifts to Mezzabarba. The small buildings in the outer courtyard of Yangxin Hall were where eunuchs on duty resided, and officials waited here to be summoned by the emperor.

Kunning Palace – The residence of the empress.

Cining Palace – The residence of the empress dowager.

Ningshou Palace – The residence of the retired emperor.

Junji Office – The central power hub after the reign of Emperor Yongzheng, where the Grand Councilor of Military Affairs worked.

Qinan Hall – The hall dedicated to the worship of Xuantian Shangdi (the Primordial Emperor). On New Year’s Day each year, an altar was set up inside the Tianyi Gate, and the emperor offered incense here. On festive occasions, rituals and ceremonies were held in Qinan Hall, presided over by Taoist officials. The affairs of Qinan Hall were managed by eunuchs and Taoist priests.

Chinese palaces and dragons

Chinese palaces and dragons have a deep and intertwined cultural significance. Dragons hold a prominent place in Chinese mythology, folklore, and symbolism. They are considered divine creatures associated with power, prosperity, and good fortune. Chinese emperors, as the ultimate rulers, often incorporated dragon motifs into their palaces as a symbol of their authority and legitimacy.

In Chinese imperial architecture, dragons can be found in various forms and locations within palaces. Here are a few examples:

Dragon-Themed Roofs: Traditional Chinese palace roofs are often adorned with decorative ridge ornaments called “dragon tiles” or “imperial roof decorations.” These curved ceramic tiles depict dragons in different poses and are placed along the ridges of the palace roofs, symbolizing the emperor’s supreme status.

Dragon Carvings: Intricate dragon carvings can be found on palace walls, pillars, and doorways. These carvings showcase the dragon’s serpentine body, claws, and fierce expression. Dragons carved in stone or wood are believed to bring protection and auspicious energy to the palace.

Dragon Throne: The imperial throne within the palace is typically designed with dragon motifs. The backrest of the throne often features a magnificent dragon carving, emphasizing the emperor’s connection to the dragon as a symbol of power and authority.

Dragon Screens: Decorative screens with dragon motifs are used to separate different areas within the palace. These screens often depict dragons surrounded by clouds or other auspicious symbols, reinforcing the emperor’s regal presence.

Dragon Embroidery: Intricate dragon embroidery can be seen on imperial robes, curtains, and tapestries within the palace. These embroidered dragons symbolize the emperor’s noble status and the celestial blessings bestowed upon him.

The use of dragon symbolism in Chinese palaces reflects the deep-rooted belief in the dragon’s auspicious qualities and its association with imperial power. Dragons are considered protectors of the emperor and the nation, and their presence in palaces is believed to bring prosperity, fortune, and harmony. The integration of dragons into palace design is a testament to the rich cultural heritage and symbolism that permeates Chinese architecture.

Chinese palaces and Phoenix

Chinese palaces also incorporate the imagery of the phoenix, a mythical bird that holds great significance in Chinese culture. The phoenix is often associated with feminine qualities, such as grace, beauty, and prosperity. It symbolizes virtue, harmony, and the empress or empress dowager in the context of the imperial palace.

Here are some ways in which the phoenix is represented in Chinese palaces:

Feng Huang Decoration: Feng Huang, the Chinese term for the phoenix, is often depicted in palace decorations. Similar to dragon carvings, phoenix carvings can be found on palace walls, pillars, and doorways. These intricate carvings showcase the elegant and majestic form of the phoenix.

Phoenix-Themed Roofs: Just like dragon tiles, phoenix-themed ridge ornaments can be seen on the roofs of palaces. These ceramic decorations, known as “phoenix tail tiles” or “imperial roof decorations,” are placed along the ridges of the palace roofs. They symbolize the empress’s status and authority.

Phoenix Embroidery: Phoenix motifs are commonly embroidered on imperial robes, curtains, and tapestries within the palace. The embroidered phoenix designs often feature vibrant colors and intricate details, representing the empress’s regal presence and auspicious blessings.

Feng Huang Hall: Some palace halls are named after the phoenix, such as the “Feng Huang Hall” or “Hall of the Phoenix.” These halls are often associated with the empress’s residence or used for important ceremonies related to the empress or imperial family.

Symbolic Representation: In addition to physical depictions, the phoenix is symbolically represented through various elements within the palace. For example, the phoenix may be depicted on palace furniture, decorative screens, or porcelain vases.

The presence of the phoenix in Chinese palaces reflects the cultural symbolism and reverence given to this mythical creature. It represents the empress’s role as the counterpart to the emperor, embodying feminine virtues and bringing prosperity and harmony to the imperial court. The combination of dragon and phoenix symbolism in palace design signifies the balance of yin and yang, male and female, and the harmonious rule of the imperial couple.

It’s important to note that the specific usage and representation of dragons and phoenixes may vary in different palace complexes and historical periods. However, the overarching symbolism and cultural significance of these mythical creatures remain consistent throughout Chinese palace architecture.

Chinese palaces and lions

Chinese palaces often feature the imagery of lions, which hold significant cultural symbolism in Chinese tradition. Lions, known as “shi” or “stone lions” in Chinese, are believed to possess powerful and protective qualities, and they are commonly depicted as guardians or sentinels at the entrances of palaces, temples, and other important buildings. Here are some aspects of lions in relation to Chinese palaces:

Guardian Lions at the Entrances: Lion statues, usually created in pairs, are placed on either side of the entrances to Chinese palaces. These lions are known as “Foo Dogs” or “Shi Lions” in the West, although they are more accurately referred to as “Stone Lions” in Chinese. The male lion, often depicted with a ball under its paw, represents protection and warding off evil spirits, while the female lion, usually depicted with a cub under her paw, symbolizes nurture and protection of the building and its occupants.

Symbol of Power and Authority: Lions are seen as symbols of power, strength, and authority in Chinese culture. Placing lion statues at the entrance of a palace signifies the grandeur and importance of the building, and it also serves as a visual representation of the ruler’s dominion and protection over the palace and its inhabitants.

Architectural Decorations: Lion motifs can be found as decorative elements throughout the palace architecture. They may be carved or painted on pillars, beams, roof eaves, and other structural components. These decorative lions further enhance the majestic and imperial atmosphere of the palace.

Symbolic Presence: Beyond their physical representations, lions hold symbolic significance within the palace. They are believed to possess the ability to repel evil spirits, protect against malevolent forces, and ensure peace and prosperity within the palace walls.

Ceremonial and Ritual Use: In certain palace ceremonies and rituals, lion dances may be performed. These lion dances involve performers dressed as lions, mimicking their movements and characteristics. The lion dance is considered a traditional art form and is often performed during festive occasions or to celebrate important events within the palace.

Lions in Chinese palace architecture not only serve as decorative elements but also carry deep cultural and symbolic meaning. They represent protection, power, and authority, signifying the importance of the palace as a seat of imperial governance. The presence of lion imagery within palaces creates a sense of majesty, strength, and auspiciousness, contributing to the overall grandeur and significance of these architectural marvels.

Chinese palaces vs European palaces

Chinese palaces and European palaces represent distinct architectural styles, cultural influences, and historical contexts. Here are some key differences between Chinese and European palaces:

Architectural Style:

Chinese Palaces: Chinese palaces typically feature traditional Chinese architectural elements such as large courtyards, intricate wooden structures, curved roofs with upturned eaves, and colorful decorations. They often emphasize horizontal layouts, with buildings arranged around central courtyards and interconnected by covered walkways.

European Palaces: European palaces exhibit a range of architectural styles based on the region and time period. They include Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, and other architectural influences. European palaces are often characterized by symmetrical designs, elaborate facades, grand staircases, domes, and ornate interior decorations.

Cultural Influences:

Chinese Palaces: Chinese palaces are deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture, influenced by Confucian principles, Feng Shui, and imperial symbolism. They reflect the hierarchical structure of Chinese society, with specific architectural arrangements designated for different ranks and functions within the palace complex.

European Palaces: European palaces reflect the cultural and artistic trends of their respective regions and time periods. They often showcase the wealth, power, and artistic patronage of monarchs and nobility. European palaces also incorporate elements of classical Greek and Roman architecture, reflecting the influence of antiquity.

Historical Context:

Chinese Palaces: Chinese palaces have a long history dating back thousands of years, with the most well-known examples being the palaces of the Chinese emperors. They evolved over different dynasties and underwent significant changes in design and layout. Chinese palaces were centers of political power, where emperors conducted state affairs, performed rituals, and resided with their families.

European Palaces: European palaces emerged during various historical periods, such as the Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo eras. They were built by monarchs and nobility as symbols of their status and authority. European palaces often served as residences, centers of governance, and venues for courtly activities, cultural events, and social gatherings.

Size and Layout:

Chinese Palaces: Chinese palaces tend to have larger footprints, encompassing vast complexes with multiple courtyards, gardens, pavilions, and halls. The Forbidden City in Beijing is a prime example of a sprawling Chinese palace complex.

European Palaces: European palaces vary in size, ranging from smaller royal residences to expansive complexes. While some European palaces feature extensive gardens and parks, they generally have a more compact layout compared to Chinese palaces.

These are broad generalizations, and there are exceptions and variations within each category. Both Chinese and European palaces represent the architectural and cultural legacies of their respective regions, showcasing the richness and diversity of human history and creativity.

China’s vast land is adorned with an impressive number of palaces, each with its unique charm and historical significance. From the renowned Forbidden City to lesser-known regional palaces, these architectural wonders showcase China’s rich cultural heritage and offer a window into the country’s imperial past. Exploring these magnificent palaces allows visitors to immerse themselves in the grandeur and splendor of ancient China, unraveling the stories of emperors, dynasties, and the artistic achievements of a bygone era.