As summer arrives and temperatures soar, staying cool and comfortable becomes a priority for many. However, ancient civilizations, like Ancient China, did not have access to modern amenities like air conditioning. Yet, they developed various techniques and practices to combat the intense summer heat and maintain a pleasant living environment. In this article, we will explore some of the methods employed by the ancient Chinese to avoid the summer heat and enjoy a refreshing and comfortable season.

when is summer in China?

Summer in China typically begins in June and lasts until August. However, it’s important to note that China is a vast country with diverse climates, so the timing and duration of summer can vary across different regions. In the northern parts of China, summer may start in late May or early June and last until September. In southern regions, summer can be longer, starting as early as April and extending until October. Additionally, some areas, such as high-altitude regions or coastal areas, may experience milder temperatures during the summer months. It’s always best to refer to specific regional weather patterns and forecasts for accurate information on summer timing in different parts of China.

How hot was ancient China?

The hottest summer in history occurred in the eighth year of the Qianlong reign, in the year 1743 AD. According to the “Compendium of 3,000 Years of Chinese Meteorological Records,” Volume 3, “Meteorological Records of the Qing Dynasty (Part 1),” high temperatures affected almost half of China that year. The entire North China region, including Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong, experienced exceptionally scorching heat, making it a superheatwave. Records of the extreme heat in the eighth year of Qianlong can be found in various historical chronicles. Here are a few examples:

Beijing: “In June, Bingchen (July 25), scorching heat prevailed in the capital.” (“Continuation of the Eastern China Chronicles”)

Tianjin: “In May, the heat was unbearable, and the soil and rocks were scorched. The mastheads melted, and many people died from the heat.” (Tongzhi’s “Continuation of Tianjin County Chronicles”)

Gaoyi, Hebei: “From May 28 (July 19) to June 6 (July 26), it was oppressively hot, with walls providing no shade, and the lead and tin melting under the midday sun. Many people died from thirst.” (Republic of China’s “Gaoyi County Chronicles”)

Fushan, Shanxi: “In May, there was extreme heat, and many travelers on the roads perished. It was even worse in the capital, with traders from Fushan dying from the heat.” (Qianlong’s “Fushan County Chronicles”)

Gaoqing, Shandong: “A severe drought spanned thousands of miles, and indoor objects were scorching hot. Trees withered in the scorching southwestern winds. In June, many people fled from Tianjin to Nanwuding Prefecture, and many travelers died from the heat.” (Qianlong’s “Qingcheng County Chronicles”)

From these records, it is evident that the entire North China region was in a state of extreme heat. The “Continuation of the Eastern China Chronicles” used the term “wei shu” to describe the high temperatures, likening the weather to a fierce tiger ready to devour people.

In Beijing, the situation was particularly dire that year. How many people died from the heat in Beijing alone? According to statistics cited by Song Junrong, an official of the imperial court, “From July 14th to 25th, approximately 11,400 people died from the heat in the vicinity of Beijing and within the city.” The actual death toll was likely higher, considering other affected areas. The magnitude of the fatalities can be imagined.

How high were the temperatures during the hottest summer in history? According to Zhang De’er, the director of the Paleoclimate Research Office at the National Climate Center of the China Meteorological Administration, and the chief expert in climate change research, the temperature values from July 20th to 25th in 1743 exceeded 40°C. Among them, the temperature on July 25th was the highest, reaching an astonishing 44.4°C.

To this day, this extreme temperature record has not been surpassed. In the thirty-first year of the Republic of China (1942 AD) and in the summer of 1999, two extreme temperature records were set in North China, reaching 42.6°C and 42.2°C, respectively, still around 2°C lower than during the eighth year of Qianlong.

in ancient China summer was known as

In the traditional Chinese calendar, the summer months are the fourth, fifth, and sixth lunar months. They are respectively known as Mengxia (early summer), Zhongxia (midsummer), and Jixia (late summer). Mengxia is also referred to as “Chuxia,” “Shouxia,” or “Huai Xia,” all of which are alternative names for the fourth lunar month. Zhongxia corresponds to the fifth lunar month and is also called “Chao Xia,” meaning “transcendent summer.” Jixia represents the sixth lunar month, which is the end of summer.

In ancient times, summer was referred to as “Zhu Ming.”

how to beat summer heat naturally in Ancient China?

In ancient China, people beat the summer heat naturally by wearing loose-fitting clothes, using hand-held fans, seeking shade, drinking cooling herbal teas, consuming refreshing foods, taking cool baths, balancing Yin and Yang, resting during the hottest hours, utilizing water bodies, and creating proper ventilation.

Cooling Off with Hand Fans:

Ancient Chinese people primarily relied on hand fans to beat the summer heat. These fans were often made of bamboo and were referred to as “yao feng” or “liang you” in Chinese. Wealthier households would purchase fans made of silk fabric, which were lighter to wave. Some literati would even write poems or paint on the fan surface, adding a touch of artistic charm. For the privileged class, using a “human-made breeze” from a hand fan brought immense pleasure during scorching summers.

Waving a fan requires coordination between fingers, wrist, shoulder joints, and muscles in the upper body. During the peak of summer, elderly individuals often used hand fans to cool themselves, providing an opportunity to exercise their upper limbs, joints, and muscles. Elderly people should consciously use their left hand more while fanning in summer, effectively preventing and reducing the occurrence of vascular diseases.

Ancient Chinese Icebox:

In ancient times, there were also iceboxes called “bing jian” in Chinese. They were typically made of wooden frames using materials such as rosewood, huanghuali wood, or cypress. The icebox had two layers, with the outer layer holding ice and the inner layer used to chill fruits, vegetables, and wine. Additionally, the lid of the icebox had several holes to release cold air, transforming it into a combination of an icebox and air conditioner.

Bronze Icebox:

The bronze icebox, known as “qing tong bing jian” in Chinese, was an ancient refrigeration device invented during the Warring States period in China. The bronze icebox unearthed in 1977 from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng in Suixian County, Hubei Province, consisted of a bronze container and a nested bronze vessel. The principle of the icebox relied on surrounding the vessel with ice, which chilled the wine inside.

In ancient China, people enjoyed drinking warm wine as it was gentle on the stomach. However, during the summer, they also craved cold wine to beat the heat. Located in the southern region, the state of Chu particularly relished drinking chilled wine during scorching summers, offering a great pleasure.

Wooden Icebox:

During the Qing Dynasty, natural ice refrigeration was commonly used in the imperial court, employing a wooden icebox referred to as “bing tong” or “yang tong” in Chinese. It evolved from the ancient ice container known as “bing jian.” These iceboxes were typically made of wood, such as rosewood, huanghuali wood, or cypress. They had a wide mouth and a narrow base, resembling a scoop, with a thick wooden lid. Copper hoops were fastened around the waist of the box for reinforcement, and copper rings were attached to the sides for easy transportation. The box had four legs with mud antonie to prevent dampness.

These iceboxes were not only aesthetically pleasing but also structurally sound, exhibiting similarities to modern refrigerators. The inner part of the box used lead or tin, which had weak thermal conductivity, providing good insulation and prolonging the use of natural ice while preventing the melting ice from eroding the wooden body. The lid typically consisted of two pieces, one fixed at the box’s opening and the other serving as a movable panel. When in use, the movable panel could be removed, allowing ice to be placed inside the box to chill fruits, beverages, and other food items. The bottom of the box had small holes for draining melted ice, ensuring cleanliness, while the lid featured hollow ventilation holes to release cold air, helping to lower the temperature and serve as an “air conditioner.” Due to the higher cost of wooden iceboxes, they were mainly used in the imperial court and affluent households, resulting in limited surviving examples.

Cloisonné Icebox:

The Palace Museum in Beijing houses a pair of cloisonné iceboxes from the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty, showcasing their unique characteristics. These iceboxes were identical in size and shape, weighing 102 kilograms each, with a height of 45 centimeters. Both the upper and lower parts were square, with the sides measuring 72.5 centimeters and the bottom measuring 63 centimeters. The boxes were made of wood with a lead interior, while the surface featured cloisonné craftsmanship. The lid and the sides of the box displayed intertwining auspicious flower patterns, while the bottom showcased plum blossom decorations, exuding vibrant colors and exquisite craftsmanship. The edges of the lid were gilded and inscribed with the phrase “Made by imperial order of the Qianlong Emperor of the Great Qing.” The box had four sturdy double dragon handles on each side, providing an elegant and convenient grip for transportation. Additionally, each icebox was accompanied by a mahogany stand, weighing 21 kilograms and standing at 31 centimeters tall. The stand had four corners adorned with animal face patterns, matching the icebox in both design and craftsmanship, creating a harmonious unity.

In addition to common ice storage methods such as ice cellars, the ancient Chinese also had “iceboxes.” In 1977, a bronze icebox was unearthed from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng in Suixian County, Hubei Province. It consisted of a bronze container and a nested bronze vessel, representing an early form of icebox. The working principle of the icebox involved surrounding the vessel with ice, which cooled the wine, fruits, and other items inside. During the Qing Dynasty, the use of wooden iceboxes that utilized natural ice became prevalent in the imperial court, known as “bing tong” or “yang tong.” The Palace Museum also houses a pair of cloisonné iceboxes from the Qianlong period, representing the pinnacle of ancient Chinese ice storage devices. By the Qing Dynasty, ice had become relatively widespread and was no longer exclusive to the royal court. A poem by the Qing Dynasty poet Wang Shizhen mentions “the sound of bronze bowls calling out to sell ice,” referring to ice vendors in Beijing who attracted customers by clinking copper cups together. At that time, people enjoyed sucking on ice cores and eating shaved ice, making chilled food a popular way to beat the summer heat.

Jade Pillow:

Jade is known for its cool and refreshing properties and is often referred to as “cold jade.” Utensils made of jade are suitable for cooling and relieving heat. In Li Qingzhao’s poem, “On the Double Ninth Festival,” she mentions a “jade pillow” in the line “Halfway through the night, the coolness begins to seep through the jade pillow and silk curtain.” The “jade pillow” mentioned here is likely a porcelain pillow, which is smooth and radiant like jade. Resting on it during summer brings a refreshing coolness to the body.

Porcelain Pillow:

Porcelain pillows have a pillow surface that generally does not exceed 20 centimeters in length. They are hollow on the inside with ventilation holes at the bottom, allowing air circulation. The porcelain’s glazed surface feels cool to the touch, giving the sensation of “moonlight shining through half-opened windows and the wind of predawn hours with a single pillow.”

Among porcelain pillows, the rarest are the Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln “Child’s Head” pillows. They depict a child’s head with arms supporting it, lying face down on a bed. They have a charming and adorable appearance. It is said that Emperor Qianlong had a great fondness for these “Child’s Head” pillows. Upon receiving one, he was inspired to compose a poem: “The porcelain pillow emits a spiritual aura, surpassing even jasper and coral. While asleep, one is unaware of the clouds, and the dreams of butterflies bring tranquility.”

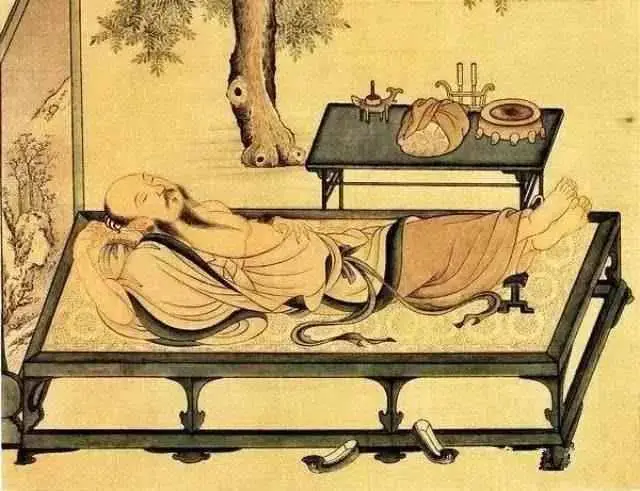

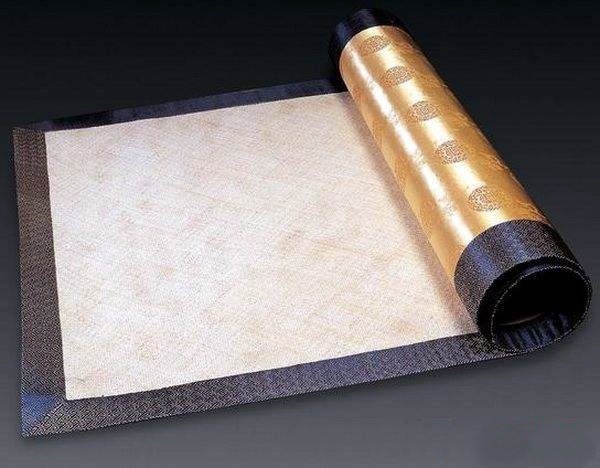

Cooling Mat:

Ancient people commonly used cooling mats, which were woven from materials such as rattan, reeds, and bamboo. The most luxurious type was the ivory mat. It is said that during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty, he presented an ivory mat to his favored consort, Lady Li. Another type of cooling mat was made of silk fabric. According to the description by Liu Xiaoyi, a person from the Southern Liang Dynasty, when using this mat, one would feel as if the summer room had already turned cold and would even desire to wear a winter fur coat. Even in scorching heat outside, there was no need for a fan.

Bamboo Wife:

The “bamboo wife” is a cylindrical bamboo item used to cool down in ancient times. During the sweltering summer, people enjoyed lying on bamboo mats, and the bamboo wife, made of woven bamboo, provided a cool and refreshing experience. It could be embraced or used as a footrest. In refined households, they would even place mint, gardenia flowers, jasmine, and other fragrant herbs in the middle, which helped relieve fatigue and enhance the scent when embraced while sleeping. Hence, it was also known as the “lady of a hundred flowers.”

Anecdote about the Bamboo Wife:

One day, Su Dongpo teased Foyin, a Buddhist monk, asking, “Do you have a wife?” Foyin chuckled and replied, “Yes, I have two.”

This surprised Su Dongpo, and Foyin explained with a smile, “In the summer, I embrace the ‘bamboo wife,’ and in winter, I hold the ‘hot water bottle.’ Aren’t those two wives?”

Upon hearing this, Su Dongpo burst into laughter.

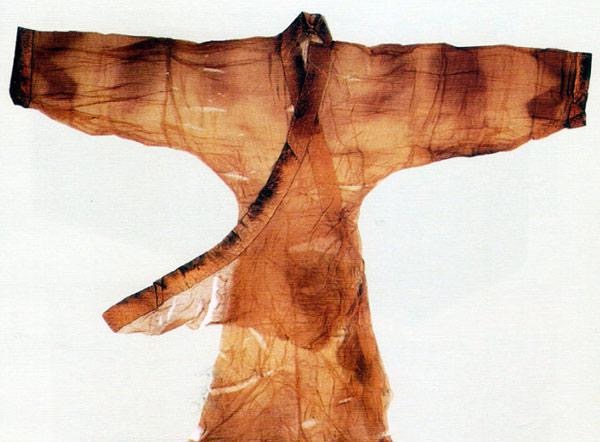

Silk Clothing:

Gehan Yi: A Garment for Beating the Heat

In ancient times, gauze was a premium fabric widely used during the summer. As the temperature gradually rose from Xiaoman to Mangzhong, people started wearing silk and gauze garments with twisted yarns and small holes, offering a stable structure and excellent breathability. During the hottest period in June of the lunar calendar, they would switch to wearing “gehan yi” or “gehan garments.” Gehan, a perennial herbaceous plant, provided fibers that were used to weave gauze, making it the most sheer and cooling material.

For common people engaged in daily labor, their attire during the scorching summer became more casual and simple. They could forgo outer robes and instead wear short garments, short sleeves, or even lightweight undershirts and vests. For the lower body, they wore shorts, and while working, they could simply tie their upper garments around the waist, opting not to wear boots and socks but instead opting for linen shoes or sandals for easy movement. In the painting “Qingming Shanghe Tu,” we can observe many commoners wearing only vests, which isn’t much different from today’s attire.

When faced with unbearable heat, people invented a garment called “gehan yi.” It involved wearing a bamboo garment, made by connecting small bamboo pipes into a net-like structure, beneath the outer clothing. This allowed air to circulate and sweat to evaporate, keeping the outer garment separate from the body. It was commonly known as the “sweat-blocking garment.”

“Dong Ri Qi Qiu, Xia Ri Gehan” was a saying that reflected the seasonal dressing preferences of ancient people. After satisfying their summer cooling needs through food and drinks, they naturally placed significant importance on clothing as the most direct means of cooling. Just as there were heavy winter clothing for winter, there were lightweight feather garments specifically designed for summer.

Ancient chinese indeed dedicated great efforts to clothing. As early as a thousand years ago, they extracted fibers from gehan grass and used them to make garments. These fabrics were made even lighter and thinner to combat the heat.

From our modern perspective, when faced with intolerable heat, people nowadays tend to wear shorts for convenience. Interestingly, our ancient counterparts also had their own version of shorts. Although later constrained by traditional feudal norms, people would wear short shirts, avoiding more complex garments.

However, considering the requirements of traditional etiquette, people still tended to dress conservatively. Therefore, to combat the summer heat, they put great effort into the fabric of their clothing.

Gauze fabric was considered the lightest and most comfortable at the time. Despite its intricate manufacturing process, when we look back at the ancient techniques of garment-making, we can’t help but be amazed.

For instance, the plain gauze garments unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tomb, despite enduring thousands of years, have not decayed. These garments appear incredibly lightweight and ethereal, evoking our admiration for the wisdom of ancient people.

However, these precious garments were mostly confined to the upper echelons of society. Emperors would gift such luxurious garments and fabrics to their favored ministers.

While it’s true that precious silk was exclusive to the upper class, for the common people, simplifying dress codes and opting for lightweight garments still achieved the purpose of beating the summer heat. It demonstrates the wisdom of our ancient ancestors in their approach to clothing.

Food:

Ice Blocks

In ancient times, without the luxury of electric refrigerators, people stored ice blocks in ice cellars. Usually, government officials would store natural ice and snow in ice cellars during the winter, and when summer arrived, they would retrieve the ice blocks or white snow and place them in their living spaces, creating a “cooling plate.” As the ice and snow melted, they released a cool breeze, providing a cooling effect comparable to modern air conditioning without energy consumption or environmental pollution. By the Ming and Qing periods, this method of using ice blocks to cool down had become common among ordinary households. During the peak of summer, both officials and commoners would use ice extensively, taking a bucket of ice, drilling a hole in the ground, and enjoying the cool breeze throughout their homes.

The ancient Chinese book “Zhou Li” recorded the early knowledge of preserving natural ice. However, this method of ice storage was not convenient to use. The process involved storing ice blocks harvested in the winter in underground ice cellars and using them in the following winter, resulting in substantial consumption. Therefore, this ice storage method was initially only feasible for upper-class households, as it required significant resources and effort.

In the late Tang dynasty, our ancestors accidentally discovered the use of saltpeter to produce ice, which was a significant breakthrough. This invention of ice-making technology allowed ice blocks to become accessible to ordinary people during the hot summer months.

With the popularization of ice-making technology, itinerant vendors selling cold drinks started appearing in the streets and alleys. “Tao Shui” or cold drinks were already being sold before ice blocks were widely available. Astute merchants recognized the business opportunity, reserving a large amount of ice during the winter. Although this method consumed considerable resources, they understood the high value of ice blocks during the summer due to the enormous demand. Selling cold drinks was a profitable trade during the scorching heat.

In addition to relying on ice blocks to make cold drinks, in ancient times, each village and household had a water well for convenient access to water. Since the well water was deep underground, it had a lower temperature compared to the surface, allowing people to use the cold well water to make chilled beverages. Alternatively, they could immerse items that needed to be chilled into the well water, achieving a similar effect to refrigeration.

Ancient Ice Cream

During the Northern Wei dynasty, there were already various dairy products, as recorded in the book “Qi Min Yao Shu.” By the Tang dynasty, a dessert called “Su Shan” was made, resembling a giant cream cake. However, it was made only during cold weather, and there is no mention of adding ice and consuming it in the summer. Chen Ji, a poet from the Yuan dynasty, mentioned “ice cream” in his writings: “Color reflecting on the golden plate, grace accompanied by ice cream given first.” This ice cream resembled real snow made of lactose. In the streets of Hangzhou during the Southern Song dynasty, there were also many chilled soups and beverages to beat the heat, such as Gan Dou Tang, Dou Er Shui, Xiang Ru Yin, coconut wine, strained pear juice, plum juice, ginger honey water, papaya juice, agarwood water, and lychee paste water.

During the Qing dynasty, the imperial court had a variety of cooling beverages. The most famous one was the “Ice Bowl,” made from ingredients such as lotus seed and snow fungus soup, sweet melon and lotus root, almond tofu, raisins, fresh walnuts, huai yam, and date paste cake. After chilling, it was incredibly refreshing to consume.

Chilled Summer Snacks

In the book “Gong Nu Tan Wang Lu” written by Jin Yi, a palace maid, she described how Empress Dowager Cixi enjoyed summer refreshments in the Summer Palace: “The famous snacks in the palace were miscellaneous tidbits, such as autumn and winter preserved fruits and dried fruits, and summer ‘sweet bowls.’ The ‘sweet bowl’ was a summer snack made by thinly slicing fresh lotus root sprouts, combining them with the flesh of sweet melon after removing the seeds, and serving them chilled. Green walnuts were cracked open, and the astringent layer of tender skin inside was peeled off. Then, grape juice was poured over them, and they were chilled before eating.” This gives us a glimpse into the Qing palace’s use of ice during the summer.

According to the memoirs of Yehenara Yuechao, the grandnephew of Empress Dowager Cixi, who accompanied her to Xi’an to escape the Eight-Nation Alliance in 1900, he wrote in his memoir “Gengzi-XinChou Sui Luan Ji Shi”: “During the summer of the Xin Chou year (1901), in Shaanxi, Empress Dowager Cixi wanted to have chilled plum soup. The weather in the Guanzhong region was hot, and there was no ice available. Local people suggested that there was an ice cave in Mount Taibai, which was more than a hundred miles southwest of Chang’an. The cave was deep and cool, and the ice inside had not melted for thousands of years. They ordered local officials to send people to Mount Taibai every day to transport the ice for the imperial kitchen.”

Jade Tube Drinks

Ancient people also used lotus leaves as cups for drinking. They would take fresh lotus leaves with stems, pierce the lotus hearts, and make holes that connected to the hollow stems. They would then fill the lotus leaves with delicious wine and bend the hollow stems into a shape resembling an elephant’s trunk, allowing them to sip the wine from the end of the stem. This elegant way of drinking wine was named “Jade Tube Drinks.” The wine infused with the lotus leaves gained a hint of the lotus’s fragrance, and it was said, “The taste of wine mixed with lotus scent, the cool fragrance surpassing water.” Just the name “Jade Tube Drinks” itself evokes a sense of coolness.

Melon and Fruit Beverages

To beat the summer heat, people in ancient times consumed melons and fruits and drank various beverages. In Zhou Mi’s book “Wu Lin Jiu Shi,” he mentioned that the variety of summer refreshments in ancient times was abundant, including new lychees, Junting plums, waxberries, fresh lotus roots, sweet melons, peppered loquats, purple water chestnuts, green lotus seeds, apples, golden peaches, preserved Changyuan plums in honey, papayas, bean sprout water, lychee paste, golden orange water dumplings, mustard and spicy drinks, white rice wine, cold water, and refreshing icy treats.

Under the category of “cold water,” there are numerous subcategories, including Gan Dou Tang, coconut wine, Dou Er Shui, Lu Li Jiang, plum juice, ginger honey water, papaya juice, tea water, agarwood water, lychee paste water, bitter water, golden orange dumplings, snow-frothed shrink skin drink (referred to as “shrinking spleen” in Song-era prints), plum blossom wine, Xiang Ru Yin, Wu Ling Da Shun San, and Zi Su Yin. Ancient people also enjoyed chilled fruits and beverages during summer.

summer building:

Tang Dynasty Air-Conditioned Chambers

During the Tang and Song dynasties, seeking relief from summer heat became an important aspect of the royal court and high-ranking officials’ lives, and their methods of cooling off were extravagant. In the Tang Dynasty, the emperor built cool chambers specifically for escaping the summer heat within the palace. These chambers were equipped with mechanically-driven cooling devices. These devices used a circulating system of cold water, with rotating fan wheels generating airflow to deliver cool air into the chambers. Simultaneously, water was mechanically pumped to the roof and allowed to flow down along the eaves, creating a water curtain that stirred up coolness, effectively combating the heat. This cooling system utilized natural water cooling and had significant cooling capabilities.

The ancient “cool chambers” of that time can be likened to modern air-conditioned rooms. The Tang Dynasty palace cool chambers were often built near water and utilized fan wheels similar to waterwheels to generate airflow and deliver cool air into the chambers. Water was also carried to rooftop tanks using waterwheels, allowing it to flow gently down the edges of the roof, creating an artificial water curtain that stirred up coolness and provided a cooling effect.

Summer Retreat in Imperial Palaces

In the Qing Dynasty, the emperor enjoyed retreating to summer palaces during the summer season. Wherever the emperor and his consorts resided, scaffolding was erected before the summer solstice, surpassing the palace roof and covered with woven reed mats. Although the canopy disrupted the visual appeal of the palace, it served as insulation. Bamboo curtains were hung on the doors of the emperor and his consorts’ sleeping chambers to ward off mosquitoes and flies. These bamboo curtains were intricately woven and finely meshed, showcasing exquisite bamboo craftsmanship. When the consorts went for walks, palace maids and eunuchs would carry incense burners to drive away mosquitoes and flies. Fans were essential items for the emperor and his consorts, including palace fans, round fans, feather fans, folding fans, and more. In the Qing Dynasty, mechanical fans were already present in the imperial palace. They were designed as feather fans held by child-like figures. By winding up a mechanism, the feather fan would move up and down, generating a gentle and cool breeze.

Bamboo and Willow:

Bamboo and willow were extensively used in Ancient China due to their natural cooling properties. These materials were used in the construction of furniture, blinds, and fans. Bamboo screens were hung over windows and doors to create shade and filter sunlight while still allowing air circulation. Willow branches were often placed near windows or doors and sprayed with water to cool down the passing breeze.

Gardens and Water Features:

Gardens were an integral part of ancient Chinese culture, and they served multiple purposes, including providing relief from the summer heat. Water features, such as ponds, fountains, and small streams, were incorporated into garden designs. These water elements not only created a visually appealing ambiance but also had a cooling effect through evaporation, reducing the overall temperature in the surrounding areas.

Herbal Remedies and Beverages:

Traditional Chinese medicine placed great emphasis on using herbs and natural remedies to maintain health and balance. During the summer, certain herbs were believed to have cooling properties and were commonly used in teas and beverages. Mint, chrysanthemum, and lotus leaf were popular choices for their refreshing and cooling effects on the body.

Herbal Remedies

Traditional Chinese medicine has a long history of using herbal remedies to combat heat and prevent heatstroke and colds. Medicinal soups containing herbs such as Huoxiang, Gancao, and Jinyinhua are believed to have cooling and beneficial effects. Classic herbal formulas like Huoxiang Zhengqi Tang and Qingshu Yiqi Tang are commonly used to relieve heat-related symptoms. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, people often consumed lotus seed soup as a popular method to cool down and nourish the body, benefiting the spleen and spirit. In the Qing dynasty, some individuals brewed soups using ingredients like Su Ye, Huo Ye, and Gancao, known as “Shu Tang,” which were sold on the streets.

Cooling Herbal Teas

In ancient times, during the Tang dynasty, people would boil fruits and herbs to create a refreshing “drinking water,” which can be considered the precursor to herbal teas. These “drinking water” concoctions were not only sweet and tasty but also had cooling and detoxifying properties, making them an effective way to beat the summer heat. Even today, many people enjoy drinking herbal teas and consuming refreshing foods like chilled jelly in the summer.

Conclusion

Although lacking modern technologies, the ancient Chinese possessed a wealth of knowledge and practical solutions to combat the summer heat. From architectural design principles to the use of natural materials, they developed effective methods to stay cool and comfortable during hot summers. By incorporating these ancient practices into our lives, we can draw inspiration from the wisdom of the past and find ways to beat the summer heat in a more sustainable and natural manner.