Spring and Autumn Period is known as Chunqiu Shidai or Ch’un-ch’iu Shih-tai in Chinese. It refers to a time of close to three hundred years that occurred during the Zhou dynasty’s rule in the East. The period got its name for the Spring and Autumn Annals, a book of chronicles attributed to Confucius among others.

When was the Spring and Autumn Period?

The Spring and Autumn period was an era in Chinese history from around 770 to 476 BCE (or 403 BCE according to some authorities). The Period corresponds to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. Spring Autumn was first used as a term of record, in the annals of a book of Chronicle. The record was compiled between 722 and 479 BCE by a host of officers from the royal court of the Lu Kingdom, a state of the Zhou Empire. Since this book was about the happenings of that period, scholars years later began to refer to this time as the Spring and Autumn period.

The original Spring Autumn is widely believed to have consisted of five books, two of which cannot be found, and of the remaining three only one -Zuo Zhuan, (Commentary of Zuo) was still in circulation after the Sui Dynasty. This means there is still quite a bit of information that was not available to the scholars who named the period Spring and Autumn. We will never know how the missing information could have impacted the naming of the time.

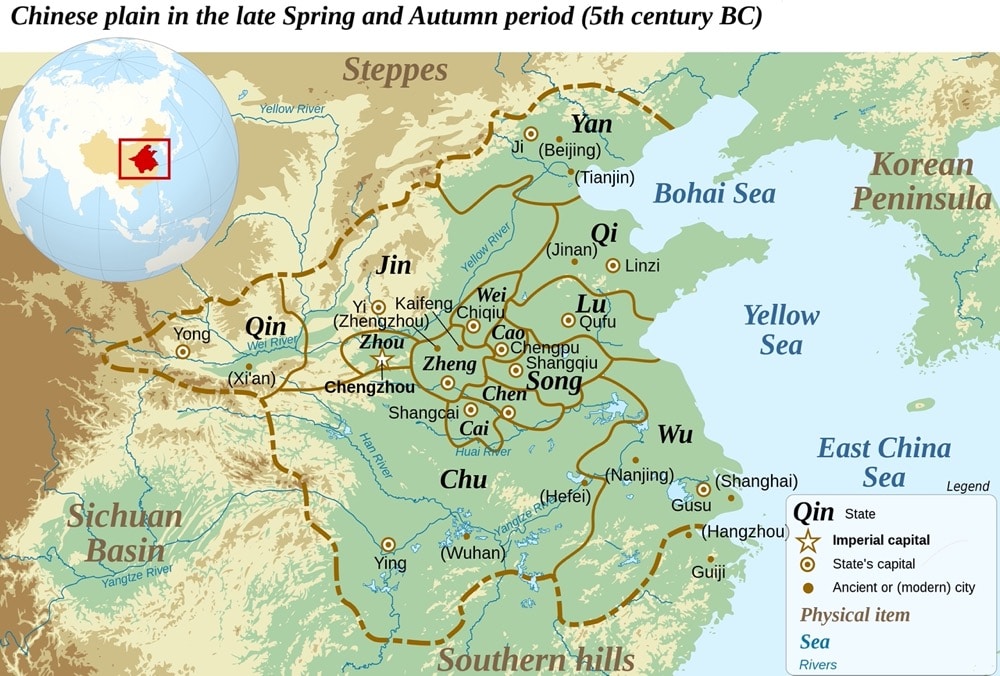

From a dynasty’s historical perspective, the Eastern Zhou, in which the Spring and Autumn period lies, falls in the middle of the longer Zhou dynasty that ran for close to eight hundred years, from 1046 to 256 BCE. At the beginning is the Western Zhou 1046-771 BCE which lasted for two hundred and seventy-five years ending with the sacking of the capital. The gave way to Eastern Zhou from about 770-476 BCE two hundred and ninety-five years. The gradual disintegration of Jin, one of the key states, signalled the end of the Spring and Autumn period in 476 BCE and the opening of the Warring States period, which ran till 221 BCE.

Why is it called Spring and Autumn Period?

In Chinese culture, “spring” symbolizes a time of new growth. “Autumn” symbolizes the time when mature leaves die off going into winter. The classical Chinese considered this to apply to humanity. The Spring in this period represented a time of new ideas shooting from all over the place, and in Autumn, the mature ideas were ready for the next season.

In Spring, which happened at the beginning and middle of this period, the existence of many small kingdoms and states with different cultures, languages, and tribal backgrounds allowed many schools of thought to exist simultaneously. These states were experimenting with different thoughts on governance. The ideas were aimed at equipping their respective governments to better their neighbours, and maybe even unite China in the future.

The Autumn referred to the ideas which had matured during this period such as Confucianism, Mohism, and Legalism, and became the foundational governance philosophies in the periods which followed.

The Spring and Autumn, therefore, represented a period rich in ideas and philosophies contending for the patronage of different Chinese royal courts. Several of these philosophies prevailed, to be carried on in the Warring States period.

The view of the state of affairs being as spring and autumn was Confucius’. Later historians including Sima Qian called it the Spring and Autumn period.

What Happened During the Spring and Autumn Period?

The Spring and Autumn period had been preceded by several hundred years of relative peace. However, the period itself was checkered with mixed fortunes. On the one hand, the period saw a decline in Zhou’s, and by extension, the old dynasty type of court power and the gradual increase of vassal states’ power. On the other, the period had a lasting impact on China’s economic, trade, educational, and intellectual growth.

The beginning of this period was marked by a political event. In 771 BCE Zongzhou, the Western Zhou capital was sacked by nomadic invaders, and the emperor was killed. His successor was forced to move the capital east to Cheng Zhou. Destabilized by losing its base, the emperor became a figurehead with no real military, left to perform religious ceremonies in Luoyang, while powerful states were consolidating power, principally through warfare.

This resulted in a shift in the economies. Survival for these states meant political and economic alliances, amassing and controlling productive wealth. To this end, major infrastructural projects including major canals, reservoirs, and roads, were undertaken, often across state boundaries. Long walls were built for protection. Traders and artisans began to gain more prominence in society.

Intellectualism and education life advanced, and chaotic as the period was, it also gave birth to three of China’s most influential philosophers. These are Confucius, (D)Lao Tzu, and Sun Tzu, and- all greatly influenced by the happenings during this period.

Confucius was born in the state of Lu. He taught about the importance of social order. His works include contributions to the” Spring and Autumn Annals”, a chronicle of the state of Lu between 722 and 479 BCE, to which this period owes its name.

Sun Tzu, was more concerned with war. The book “The Art of War” is traditionally credited to him.

Lao Tzu is credited to be the founder of Taoism.

Spring and Autumn Period clothing

Shenyi which means deep robe emerged as the main style of dressing during this period. The style was deeply rooted in mainstream Chinese ethics and morals that forbid skin exposure, and close contact between males and females. The apparel consisted of a combination of a tunic and a skirt. This fashion took hold quickly amongst the people, buoyed by emerging philosophical beliefs of social mobility.

The dressing code was important enough for a chapter in the “Book of Rites” to be dedicated to how to make the Shenyi. Great importance was attached to the upper and lower clothing for ceremonial occasions. The people of this period believed it symbolized the greater order of heaven and earth.

The design of the Shenyi needed to conform to the rites and rituals, fit the rules with proper round and square shapes, and have a perfect balance. It needed to be long so as not to expose the body, but short not to sweep the floor. The front part was made long into a large triangle at the bottom, with a straight cut top to the waist. The arms were made with long full sleeves to the elbow which folded at the fingertips. The long triangular hem was rolled to the right and tied with a silk ribbon below the waist. This ribbon was called Dadai or Shendai, on which a decorative piece was attached.

Moderately formal, the Shenyi was fit for both warriors and men of letters. For its simplicity, the Shenyi ranked second in ceremonial wear.

What differentiated social class was the color, cloth material, and jewelry. Clothes for the royals were made of silk, and the colors vermilion and yellow were reserved for nobility. Most people wore linen, of different colors except black and white which were ceremonial. Jewelry and adornment were used based on one sense of fashion, but also to signify rank. The most important adornment for men was their belt buckle. Women’s jewelry consisted mostly of hair combs and hairpins.

Conclusion

By most accounts, the Spring and Autumn period extended slightly longer than the Eastern Zhou period. This does not however take away that it was brought into being and nurtured during this dynasty.

Some of the ideas were implemented by dynasties long after the Zhou. The philosophies are taught the world over to date: Confucianism, Taoism/Daoism come to mind, and who has at least not heard about “The Art of War”?