The “futou” (幞头), also known as “zheshangjin” or “ruanguo,” is a type of soft scarf worn around the head, originating from the Han Dynasty. Because the fabric commonly used for the futou is typically dark blue or black, it is also called “wusha,” commonly referred to as the “wusha hat” in colloquial terms.

The “futou” (幞头), known as the “zheshangjin” or “ruanguo,” gained widespread popularity both within and outside the royal court and across various social classes due to its convenient wear and versatility, becoming a common attire for officials and commoners alike. The evolution and development of its style reflect the intricate balance between the hierarchical and practical aspects of official attire, while also showcasing the historical reality of ethnic integration and cultural convergence. The futou, easy to don and remove, exudes liveliness amidst its splendor, serving as a brilliant gem in Han ethnic attire. Its tradition persisted for over a thousand years, although it has since faded from the historical stage. Nevertheless, as a relic of the past, the futou evokes a nostalgic sentiment, reminding people of the deep-seated historical connections they cherish.

Futou history

The “futou” originated in the Han Dynasty, initially known as “fu jin,” before being called “futou.” It began as a square-shaped headscarf, with dimensions equal to the width of the fabric. The Han ethnic group had a tradition of growing hair long, and ancient Han men commonly wrapped a piece of cloth around their heads from front to back, tying it at the back to secure their hair for practical reasons during labor. The popularity of the “fu jin” initially surged among the common people, gradually becoming a common attire for all social classes during the Eastern Han Dynasty.

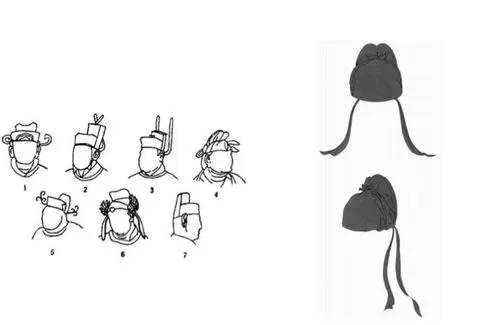

During the early Sui Dynasty, futou mostly consisted of soft wrapping and soft feet, using a piece of black gauze to wrap the hair bun from behind, resulting in a low and flat appearance with a simple structure. The “feet” of the futou referred to the remaining parts of the straps tied at the back of the head. Soft wrapping and soft feet indicated that there were no hard supports inside the main body and feet of the futou, maintaining the natural state of the fabric wrapped around the hair bun. In contrast, hard wrapping and hard feet involved adding rigid materials such as bamboo, wood, or metal inside the main body and feet of the futou, making its appearance sturdier.

During the reign of Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty (605–618 AD), a tong wood frame was introduced inside the futou, acting as a pad covering the hair bun, elevating its top part and giving it a more upright appearance. This type of internal frame in the futou was called “jinz” or “shanzi” at that time. The late Sui to early Tang period was an important period for the popularity of the futou. During the early Tang Dynasty, soft wrapping and soft feet futou were prevalent. The protrusion at the top of the futou was not very obvious, but compared to the futou of the Northern Zhou and Sui Dynasties, the early Tang futou had a more distinctive shape. During this period, the feet of the futou were made of lightweight and soft gauze, collectively known as soft feet futou.

From the early Tang to the middle Tang Dynasty, there was a variety of futou styles with diverse forms. The top part and feet of the futou underwent rich changes, but most of them were soft wrapping and soft feet futou. During the early Tang period, the feet hanging behind the head gradually lengthened, known as long-footed gauze futou. The long-footed style originally came from the palace and was mostly awarded by the emperor. In the middle Tang Dynasty, the feet gradually shortened, with some even curving upward, known as curved-footed or upward-curved-footed futou. Some futou feet were inserted into the knot at the back of the head, with two corners visible from the side for decorative purposes.

With the widespread popularity of futou, hard-lined inner linings became popular in the early Tang Dynasty, primarily made of tong wood and rattan, covered with gauze on the surface. In the middle Tang Dynasty, the fabric wrapped around the hard-lined inner linings was not fixed, requiring re-wrapping with each wear. During this period, a type of hard wrapping and hard feet futou appeared, which did not require re-wrapping and was easy to put on and take off. The structure of this type of futou was similar to soft wrapping futou, with a round top and feet unfolded in a “one” or “eight” shape behind the head, slightly smaller than the futou prevalent in the later Five Dynasties and Song Dynasty, representing a transitional style.

During the late Tang and subsequent periods, hard wrapping and hard feet futou became popular. In the late Tang period, hard wires such as iron, copper, or bamboo were added inside the feet of the futou to create a pair of hard wings, also called “upward-curved-footed futou.” Compared to soft feet futou, hard feet futou appeared more upright and shapely. To enhance the appearance of the futou, people painted the fabric on the outside to make it harder. Eventually, the inner linings disappeared, leaving only the external paint shell, with the two feet tied at the forehead either used for decoration or abandoned. This transformation brought significant changes to the structure of the futou, making it easier to put on and take off. This type of futou continued and developed during the Song Dynasty.

The appearance of hard wrapping and hard feet futou made the structure of the futou tend more towards crown-style headwear. The feet of the futou began to shift from their initial practical function towards decorative purposes, significantly influencing the way futou was worn.

During the Five Dynasties period, futou styles included straight feet, crossed feet, curved feet, upward-curved feet, and upward-facing feet. Straight feet, also known as flat or extended feet, featured the two feet of the futou extending straight outwards. During the Five Dynasties period, rulers and officials began to wear straight-footed futou, while curved-footed and hanging-footed futou coexisted during the late Tang and Five Dynasties period.

In the Song Dynasty, there was a wide variety of futou styles, such as crossed feet futou, curved feet futou, high feet futou, palace flower futou, ox ear futou, jade plum snow willow playful goose futou, silver leaf arch-footed futou, and curved-footed futou pointing backward. The inner lining was made of wood, covered with gauze on the surface, and coated with lacquer on the outside, forming a front-low and back-high stepped shape. In the Song Dynasty, the feet of the futou extended straight out to both sides, supported by iron wires inside the futou feet to keep them open and elongated, aiming to maintain a certain distance between officials during court sessions. Futou colors in the Song Dynasty were no longer limited to black, and colorful futou appeared at festive occasions such as banquets.

After the Song Dynasty, futou continued to be used in subsequent dynasties such as the Yuan and Ming, with changes in its form mainly catering to the needs of the ruling class. For example, the “wusha hat” in the Ming Dynasty had evolved into a symbol of bureaucracy and career advancement. Futou persisted in Chinese history for over a thousand years, gradually fading from the stage of clothing as the Manchu-style hat replaced it in the early Qing Dynasty.

Futou type

Futou can be classified into the following types based on their styles:

1. Flat Style Futou

The flat style futou is a type of soft-wrapped scarf with a lower and flatter top piece, also known as the “flat-headed style.” It is commonly worn by officials and civilians during leisure or banquet occasions.

2.Knotted Style Futou

The knotted style futou is also a type of soft-wrapped scarf, with an additional piece tied on top of the futou, forming a concentric knot with its two ends tied in front of the head and the other two ends knotted at the back. It is favored by junior officers and warriors.

3. Soft-footed Futou

The soft-footed futou involves using a “headband” (i.e., a wig) or a “wooden headband” to support the futou underneath, ensuring its outer appearance is smooth and fixed. The feet of the futou are thickened and painted, creating soft feet that hang down gracefully during movement. It is favored by civil officials and scholars.

4. Women’s Scarf Futou

Popular during the Tang Dynasty, women’s scarf futou was worn by palace attendants, maids, noblewomen, and women who dressed as men during that era. The scarf is smaller in size with a higher top, made of lacquered gauze, with longer ends tied at the back of the head, naturally hanging down. Decorations such as floral patterns or jade ornaments are added to the scarf for embellishment.

5. Round Top Straight-footed Futou

This type of futou involves a hard-wrapped cap with a “wooden headband” supporting it at the forehead, covered with a wrapped scarf made of rattan or iron wires and coated with lacquer. The straight feet of the futou, made of iron wires, extend flat to the sides, preferred by courtiers and local officials. It has been used in various dynasties including the Tang, Song, and Ming.

6. Square Top Hard-shell Futou

A type of hard-wrapped cap, with an inner shell made of iron wires or rattan, covered with silk or gauze and coated with black lacquer, resulting in a square and raised appearance. The straight feet, made of iron wires, extend flat or curl upwards to the sides. It was favored by Song Dynasty officials and even worn by emperors, with feet extending straight to the sides, reaching up to two feet in length.

Futou historical value

Political Culture

Futou, as a prevalent headgear during the Tang Dynasty, embodies the enlightened and liberal political system and ideological culture of that time. With diverse and flexible designs, futou was less constrained by the hierarchical dress code, representing the Tang people’s tradition inheritance, innovation, and active exploration in the field of attire. Within the official dress system of the Tang Dynasty, futou played a significant role. As the core of the ruling class, the emperor’s preferences, customs, and viewpoints influenced the aesthetic standards and social atmosphere of officials and the entire society, exerting a profound influence through immense political power. Therefore, the emperor, as the head of the state, with his influential discourse and great appeal in fashion trends, profoundly affected the changes and development directions of futou’s design. The emulation of the emperor’s attire by officials turned futou into a political symbol, signifying support and loyalty to the imperial rule. By bestowing futou as rewards, the emperor reinforced his control over the officials, while officials demonstrated their loyalty and authority by wearing the futou favored by the emperor, implicitly expressing their identification with the bureaucratic culture and status. Thus, after integrating into the official dress system of the Tang Dynasty, futou gradually acquired political functions, beyond its basic function of adornment. The naming of various futou styles during the Tang Dynasty also reflects political connotations. During the reign of Emperor Taizong, Prince Wei Li Tai innovated a new style of futou, named “Prince Wei’s Model,” aligning with the prevailing headgear fashion at the time. By the era of Empress Wu Zetian, futou’s inner lining was elevated, referred to as the “Wu Family Princes’ Model.” These names, such as “Prince Wei,” “Princes,” and “Wu Family,” carry evident political implications. By the Song Dynasty, futou was integrated into a strict hierarchical system; with the emergence of the black gauze hat during the Ming Dynasty, futou began to be associated with the power and status of officials, becoming a political tool for rulers to differentiate between ranks and demonstrate imperial authority.

Gender Culture

The phenomenon of “husband’s sleeves” refers to the widespread practice during the Tang Dynasty where women dressed in men’s clothing. This trend became prevalent, particularly during the Kaiyuan and Tianbao periods (approximately 713-756 AD), starting from the palace and gradually influencing the general population, becoming a common choice of attire for ordinary women. Women’s rights in marriage, social interaction, and education were significantly improved during the Tang Dynasty compared to previous dynasties. Although male superiority and female oppression and discrimination persisted in reality, the elevated social status of women was evident. A type of women’s scarf futou was popular among palace attendants, maids, and noblewomen during the Tang Dynasty. While this phenomenon partly stemmed from a desire for masculine qualities, overall, it indicated an acceptance of women’s gender roles.

Hierarchy Culture

The hierarchical dress system in China generally reflects a class ethic, where rulers establish authority and social status through attire, emphasizing distinctions between nobility and commoners. The “crown,” “diadem,” or “hat,” as the pinnacle of attire, is subjected to stringent ceremonial regulations, such as the style, color, material, and patterns of crowns and hats for monarchs and ministers, strictly enforced through laws. However, during the Tang Dynasty, futou was relatively free in terms of its users. Apart from the emperor, futou was worn by princes, ministers, literati, commoners, and even servants and laborers. Tang Dynasty artifacts such as scrolls, murals, and figurines depict individuals from various social strata wearing futou, including soldiers, attendants, musicians, horsemen, merchants, wrestlers, robbers, and even dwarfs used for the amusement of high-ranking officials. Futou, as a garment, gradually became universal across all classes, reflecting a society characterized by freedom and openness during the Tang Dynasty. The development of futou from its origins among the laboring masses to its integration into courtly attire, and the subsequent influence of improvements by the royal aristocracy on lower-class futou styles, embodies the dual trajectory of bottom-up and top-down development in attire. Futou was no longer exclusive to a particular class but rather the result of active interaction and transformation of attire standards among different social classes and groups.