Compasses are essential to orientation and navigation, having been in use for centuries. What you may not know about them is their Chinese roots – and that is what we will talk about in this article, alongside some interesting tidbits about their development over the years.

What is a compass in ancient China?

The magnetic needle on an ancient Chinese compass pointed in the directions of north, south, east, and west. A bowl of water or a pivot point formed the base of the Chinese compass, which featured a magnetised iron needle. The needle would automatically point in the direction of the magnetic north pole as it aligned with Earth’s magnetic field. The compass was crucial for navigation because it allowed sailors and travellers to find their way even when the stars and other landmarks were hidden from view. The compass was not only essential for navigation, but also played a role in feng shui, the ancient Chinese art of spatial arrangement meant to bring about prosperity and harmony.

What was the Chinese compass made of?

Mathematicians and common folk used ‘loadstones’, which were suspended in the air as people believed they could point freely to a northern direction, and their magnetic properties allowed people to find gems underground as well as selecting suitable sites to build houses through Feng Shui principles. When these loadstones were placed in water, they could float, and point automatically to a southern direction.

History of the Compass

There is no set time in recorded history when the compass came to be, but historical estimates put its initial development during the Han dynasty (between the 2nd Century BCE to the 1st Century AD). During this period of ancient Chinese science and mathematics, the study of earth magic (which they called geomancy) was active.

The principle of this directional navigation was what created the first compasses. Initially, there were termed as ‘south-pointing spoons’, as the lodestone needles were shaped into spoons with their ‘handles’ facing south, and could turn easily over a smooth surface. It is unclear who came up with the compass, but they were mainly useful in navigational tasks during the Song dynasty especially in 1040 AD, especially by the Chinese military.

The loadstone was later replaced by iron needles in the 6th Century, and the compass was later recorded in Europe in 1190 AD. In the 17th Century, its overall design was changed to a parallelogram shape to make it easier to balance its pin, and 1745 saw an improvement from Gowin Knight – the Knight compass. Instead of iron, the compass now used steel needles that could hold their magnetism for a longer time.

This improvement was crucial to European dominance and colonialism, as it was going through the Age of Exploration and industrialization at the same time.

When was the compass invented in ancient China?

The ancestor of the compass appeared in the Warring States period. It was made of natural magnetite and looked like a spoon with a round bottom that could be placed on a smooth “dish” and kept balanced while also freely rotating. When it was still, the handle of the spoon would point south. The ancients called it “Si Nan”, and the book “Han Feizi” from that time recorded: “The former kings established Si Nan to determine the directions of the morning and evening.” “Determine the directions” means determining the correct orientation. “Guiguzi” also recorded the use of Si Nan, as people from the Zheng state carried it with them when collecting jade to ensure they did not lose their direction. During the Spring and Autumn periods, people were already able to shape jade with a hardness of 5 to 7 into various tools, so they were also able to make Si Nan from natural magnetite with a hardness of only 5.5 to 6.5. Wang Chong of the Eastern Han Dynasty made clear records of the shape and usage of Si Nan in his book “Lunheng”.

Who invented the first compass in ancient China?

The inventor of the compass was claimed to be the Yellow Emperor, according to Chinese legend. This claim was recorded and named by the Song Dynasty scientist Shen Kuo. According to historical records, during the battle between the Yellow Emperor and Chi You on the fields of Zhuolu, Chi You created a dense fog that caused the soldiers to lose their sense of direction. To solve this problem, the Yellow Emperor created a device called the “Zhinan Cart” to show the four cardinal directions, which enabled the soldiers to navigate through the fog and ultimately capture Chi You. As a result of this achievement, the Yellow Emperor became emperor. Therefore, the compass was traditionally attributed to the invention of the Yellow Emperor.

The versions of compasses used today

The first forms of the modern compass came around the year 1300, and they were referred to as ‘dry mariner compasses’. They had three elements: a needle that pivoted freely on a pin, a glass-covered box that protected the needle, and a gimbal that supported the box and its needle.

This resulted in ‘bearing compasses’, which could measure bearings more accurately in terms of directions of objects compared with the North. This compass later led to the earliest maps being made, with the first map variants appearing in the 16th to 18th Centuries. The variants of this compass are the prismatic and surveyor’s compasses.

The other form of the compass is the ‘liquid compass’ that was mainly used in sea navigation. It involved placing a magnetized card or needle in water, which gives a more stable reading. This was a more direct descendant of the initial compasses the Chinese used, but with some improvements.

How the compass works

The earth’s magnetic fields are essential to the operation of the compass, so it is important to understand the structure of the earth to know how they work.

The earth’s core is subject to gravitational pressure, so all the minerals and metallic elements it contains remain in a liquid or semi-crystal state. Due to the pressure and resulting heat, these elements move in various directions, leading to the formation of the magnetic field we see in a compass.

Similar to all magnetic fields, the earth’s field has two major poles – south and north. These poles tend to be slightly off from the rotational axis of the earth (the basis of geographic poles), but they remain close enough to accommodate polar adjustments when navigating the earth. These adjustments are referred to as declinations.

Therefore, compasses are lightweight magnets that work using magnetized needles hanging on rotating pivots, which allows them to react in a better and more accurate way to magnetic fields. The earth’s natural magnetic north pole will naturally attract the southern pole of the needle, so this is how sailors could know the northern direction.

What was the Chinese compass used for?

Unlike its use in Europe and the Americas, Chinese people at the time were not thinking of navigation when using compasses. Instead, they relied on these instruments as a way to bring their lives and environments into harmony, which developed into Feng Shui. In terms of the instrument’s earliest mention, it is in The Book of the Devil Valley Master.

Chinese people initially used the instrument in the study of geomancy, also called ‘earth magic’, as well as fortune-telling and worship. It was only later during the 11th to 12th Centuries that they started using it as a navigational tool, spreading it eventually through trade networks to the Arabs, the East African coast, South-East Asia, and Europe.

How was the compass used in ancient China?

Rather than for navigation as it is today, the compass in ancient China was used for divination and telling fortunes. Feng Shui, the practise of arranging one’s physical space in accordance with cosmic principles, is just one example of the many rituals and practises that made use of the compass because of its supposed supernatural powers.

Magnetite, a naturally occurring mineral, has the property of pointing towards the magnetic north pole when suspended on a string, so it was used to create the earliest compasses. They had a round base like a spoon, so you could set them down on a table and spin them around. The spoon was called a “Si Nan” because its handle faced south. Fortune-tellers would consult the compass to ascertain the optimal course of action for projects like well-digging and home-building.

By the 11th century CE, the Chinese had refined the compass to the point where it could be mounted on a pivot and submerged in a bowl of water, allowing it to freely rotate and accurately indicate direction. During the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), the accuracy and navigational utility of this design were further refined when a magnetic needle was added to the pivot. Even at this time, however, the compass wasn’t used for navigation so much as geomancy and telling the future.

Why is the compass important?

The tool became indispensable to sailors and navigators because it allowed them to determine their direction without relying on astronomical cues as cultures did before. These cues were good when present, with examples including the Austronesian people that used the North Star in their navigation of the Pacific, but the problem was if there was bad weather or clouds that obscured the view.

Since compasses use magnetic needles and rely on the earth’s magnetic field, they function well even in cloudy weather, and they will always point to the north pole of the natural magnetic field. They also proved essential in navigation and map-making, resulting in the interconnected world we live in today.

How was the compass made in ancient China?

The Chinese compass was initially used for divination rather than navigation and was based on the observation that certain types of naturally occurring magnetite, a mineral containing iron oxide, had the property of pointing towards the magnetic north pole when suspended on a string.

According to historical records, the first compasses were made by carving magnetite into the shape of a spoon with a round base, which could be placed on a flat surface and rotate freely. The handle of the spoon pointed towards the south, and the device was known as “Si Nan”. It was primarily used for divination and was believed to have supernatural powers.

Over time, the design of the compass evolved, and by the 11th century CE, the Chinese had developed a compass that was mounted on a pivot and placed in a bowl of water, allowing it to rotate freely and accurately indicate direction. This design was further refined during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), when a magnetic needle was added to the pivot, greatly improving its accuracy and utility for navigation.

Why was the compass important in ancient China?

The compass was important in ancient China for several reasons:

Divination: The compass was used for divination and fortune-telling and was believed to have supernatural powers. It was an important tool for fortune-tellers, who would use it to determine the best direction for various activities, such as digging a well or building a house.

Navigation: Although the compass was not originally designed for navigation, it was eventually adapted for this purpose during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). This allowed sailors and explorers to navigate the seas with greater accuracy, which in turn facilitated trade and exploration.

Science and Technology: The invention of the compass was a significant technological achievement and a major contribution to science. It demonstrated the understanding of the magnetic properties of materials, and the development of the compass paved the way for further advancements in navigation and other fields.

Cultural Influence: The compass also had a significant cultural influence in China, where it was regarded as a symbol of wisdom and knowledge. The compass played an important role in Chinese philosophy, such as Feng Shui and Taoism, and was also used in art and literature to represent direction and guidance.

How was the magnetic compass made in ancient China?

The first magnetic compasses in ancient China were made using magnetite, a naturally occurring magnetic mineral. The compasses were shaped like a spoon with a round base and a handle that would point to the south when placed on a flat surface. The compass was known as “Si Nan” in Chinese and was primarily used for divination.

The design of the compass evolved over time, and during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the compass was improved by suspending the spoon-shaped magnetite on a silk thread or hair, allowing it to rotate freely and indicate direction more accurately.

By the 11th century CE, the Chinese had developed a compass that was mounted on a pivot and placed in a bowl of water, allowing it to rotate freely and accurately indicate direction. This design was further improved during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), when a magnetic needle was added to the pivot, greatly improving its accuracy and utility for navigation.

The magnetic needle was made by rubbing a piece of iron or steel with a lodestone (a naturally occurring magnetic rock) in a north-south direction until it became magnetized. The needle was then placed on the pivot of the compass, allowing it to point towards magnetic north.

Overall, the compass was an important technological achievement in ancient China, and its invention and development paved the way for further advancements in navigation and other fields.

compass used in feng shui

Feng shui is an ancient Chinese practise that is used to enhance the flow of energy, or Qi,” in the environment. It is believed that by harmonising the energies of a space, Feng Shui can help promote health, happiness, and prosperity. One of the key tools used in Feng Shui practise is the compass, also known as a “luopan” or “geomantic compass”.

The luopan is a circular disc that features a magnetised needle at its centre. It is surrounded by a series of concentric rings and symbols that represent various aspects of Feng Shui. The outermost ring represents the cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west), while the inner rings represent the ordinal directions (northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast), the 24 seasonal divisions, and the five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water).

In Feng Shui practice, the luopan is used to determine the orientation and placement of buildings and other structures. By aligning a building with the natural environment, it is believed that positive energy can be attracted and negative energy can be repelled. For example, the luopan can be used to determine the best direction for a building’s entrance or to identify areas where negative energy may be present.

The luopan is also used to identify various auspicious and inauspicious directions for different purposes. For example, the “wealth” direction is believed to be located in the southeast, while the “health” direction is located in the east. By aligning a building or space with these auspicious directions, it is believed that positive energy can be enhanced and prosperity can be attracted.

In addition to its practical uses, the luopan also has symbolic significance in Feng Shui practice. The circular shape of the compass represents wholeness and completeness, while the needle symbolizes the flow of energy. Together, they represent the harmony and balance that are sought in Feng Shui practise.

Overall, the compass is an essential tool in Feng Shui practise. It is used to ensure that buildings are aligned in a way that promotes harmony and balance with the natural environment and to identify auspicious and inauspicious directions for different purposes. By using the compass in this way, practitioners of Feng Shui hope to create spaces that are harmonious, balanced, and filled with positive energy.

What did the compass mean in ancient China?

In ancient China, the compass was known as “zhi nan” (指南), which literally means “point south.” The term referred to the directional function of the compass, which was primarily used to determine the direction of the south. In ancient Chinese cosmology, the south was considered to be the most auspicious direction, associated with warmth, growth, and prosperity. Therefore, knowing the direction of the south was important for many aspects of life, including architecture, agriculture, and feng shui.

The compass also held symbolic significance in ancient China. It was believed to represent the unity and harmony of the universe as well as the balance between yin and yang, the two opposing forces that underlie all of existence. The circular shape of the compass, with its central pivot point, was seen as a symbol of the unity and wholeness of the cosmos.

Moreover, the compass was associated with the ruling power of the emperor. In ancient China, the emperor was seen as the “Son of Heaven,” chosen by the gods to rule over the earthly realm. The use of the compass by the emperor and his officials symbolised their divine authority and ability to bring order to the world. The emperor was also known to carry a special compass known as the “imperial compass,” which was adorned with precious jewels and used for ceremonial purposes.

Overall, the compass held great cultural, spiritual, and practical significance in ancient China, reflecting the importance of direction, unity, and divine authority in Chinese society.

Chinese compass animals

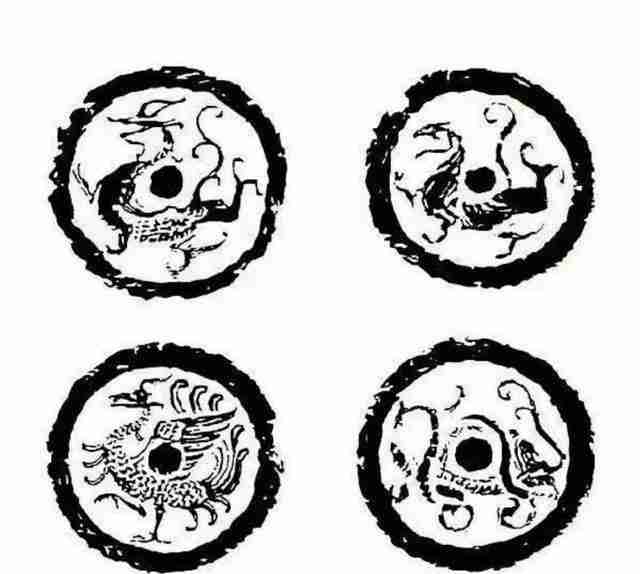

In Chinese culture, there are four animals associated with the compass directions. These animals are known as the “Four Guardians” or “Four Celestial Animals, “Four Symbols, and they are believed to have protective and auspicious powers.

The four animals and their associated directions are:

Qinglong (青龙), or Azure Dragon, represents the east and is associated with the element wood. The Azure Dragon is a powerful and benevolent creature, often depicted with a pearl or a flaming pearl, which symbolises wisdom and enlightenment.

Baihu (白虎) or White Tiger, which represents the west, is associated with the element metal. The White Tiger is a fierce and protective creature, often depicted with a sword or a whip, which symbolises its ability to defend against evil spirits.

Zhuque (朱雀) or Vermilion Bird, which represents the south and is associated with the element fire. The Vermilion Bird is a mythical bird with bright red feathers, often depicted with a pearl or a branch of cherry blossoms, which symbolizes renewal and vitality.

Xuanwu (玄武) or Black Tortoise, represents the north and is associated with the element water. The black tortoise is a wise and powerful creature, often depicted with a snake or a dragon, which symbolises longevity and wisdom.

These Four Guardians are often used in feng shui practices to balance and harmonize the energies of a space, and they are also commonly depicted in art, architecture, and literature throughout Chinese history.

Shen Kuo Compass

Song-dynasty scientist Shen Kuo was the first to record the magnetic declination, or the angle between magnetic north and true north. He discovered that rubbing a steel needle against a natural magnet would magnetise the needle and cause it to point towards magnetic north, which is slightly different from true north. Shen Kuo also introduced four methods for suspending and supporting the magnetic needle: floating it on water, placing it on a fingernail, balancing it on the edge of a bowl, or suspending it by a silk thread.

During the Song dynasty, soldiers were equipped with a type of compass called the “zhi nan yu,” or “south-pointing fish.” This compass consisted of a thin iron leaf that was cut into the shape of a fish and magnetised, allowing it to point southward even on cloudy or dark days. Eventually, the south-pointing fish evolved into the “luo pan,” or Chinese compass, which combined a magnetic needle with a compass dial.

In addition to military and navigational applications, the compass was also used in feng shui, a practice that involves using energy forces to harmonize people with their environment. Feng shui practitioners used compasses to determine the orientation of buildings and identify auspicious and inauspicious directions. The use of compasses in feng shui dates back to the Song dynasty, and the compass was also used by geomancers to survey and divide land.

Overall, the invention of the compass revolutionized navigation, military strategy, and even traditional practices like feng shui. Shen Kuo’s contributions to the understanding of magnetic declination paved the way for more accurate navigation and exploration, and the use of the compass in feng shui continues to be an important practice in Chinese culture today.

Shen Kuo recorded in his book “Mengxi Bitan” that “fang (geomancy) masters use magnetic stones to sharpen needles, which can point south but with a slight deviation towards the east, not pointing directly to the south.” This method was simple and easy to popularise, with good magnetic effects. It also led to another breakthrough in the shape of the pointer—the needle-shaped pointer. Using a needle to point, the accuracy of the pointer could be greatly improved. Thus, the compass evolved from a magnetic pointing device to a compass with a needle pointer, which was easier to popularise. Undoubtedly, this was the most important improvement to the magnetic pointing device.

Shen Kuo (1031–1095 CE) was a polymathic scholar of the Song Dynasty in China who made significant contributions to various fields of science and technology, including astronomy, geology, mathematics, mechanics, and physics. Among his many achievements, Shen Kuo is also known for his work on the magnetic compass, which he studied and improved upon in the 11th century CE.

Shen Kuo was interested in the natural sciences from a young age and was especially curious about the Earth’s magnetic field and its effects on navigation. He was aware of the use of compasses for navigation and had also investigated the magnetic compass. However, Shen Kuo was not satisfied with the accuracy of the compasses of his time, which he found to be prone to errors and deviations.

To improve upon the existing compass designs, Shen Kuo conducted a series of experiments and observations. He discovered that the needle of the compass was not fixed but had a slight wobbling motion, which he attributed to the Earth’s magnetic field being slightly tilted. To correct for this deviation, Shen Kuo designed a special compass needle that was slightly weighted on one end so that it would always point to true north rather than magnetic north. He also experimented with the use of magnetised iron filings to create a more stable magnetic field, and he observed the effects of the sun, moon, and stars on the compass needle’s orientation.

In addition to his practical improvements to the magnetic compass, Shen Kuo also wrote extensively about the theoretical principles behind its operation. He understood that the Earth’s magnetic field was not uniform and that there were variations in strength and direction across different regions. He also recognised that the compass was not affected by the Earth’s rotation but rather by the position of the magnetic poles relative to the observer’s location.

Shen Kuo’s work on the magnetic compass was influential in his time and paved the way for further improvements and innovations in navigation technology. His ideas were later disseminated throughout the world, and his design for a weighted compass needle became the standard for use in Chinese navigational instruments for centuries to come.

In addition to his work on the magnetic compass, Shen Kuo also made important contributions to other fields of science and technology. He is credited with the invention of a type of movable-type printing press, which he used to produce copies of his scientific works. He also wrote about the principles of optics and light, describing the properties of lenses and mirrors, and investigating the phenomena of reflection and refraction.

Overall, Shen Kuo’s work on the magnetic compass represents a significant achievement in the history of science and technology, demonstrating his ingenuity, curiosity, and scientific rigor. His ideas and innovations continue to inspire scientists and scholars to this day, and his legacy remains an important part of Chinese intellectual history.

Zheng He Compass

Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho) was a Chinese explorer and admiral who lived during the Ming dynasty in the 14th and early 15th centuries. He is known for leading several voyages of exploration and diplomacy throughout Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa.

Zheng He’s expeditions were made possible in part by the use of the compass, which was a critical navigational tool for seafaring voyages. The compass used during Zheng He’s time was similar to the magnetic needle compass developed in ancient China, but with some improvements.

One of the major improvements was the addition of a gimbal suspension system, which allowed the compass to remain level even as the ship pitched and rolled with the waves. This made the compass more reliable and accurate, as it was not affected by the ship’s movements.

Another improvement was the use of multiple compasses, placed at different locations on the ship. This helped to account for any errors or deviations that may have occurred in any individual compass, increasing the overall accuracy of navigation.

Zheng He’s compasses were also marked with detailed information about the locations of various ports, landmarks, and hazards along the way. This information was crucial for safe and efficient navigation, especially in unfamiliar or dangerous waters.

Overall, Zheng He’s use of the compass was a major factor in his successful navigation and exploration of new lands. His voyages helped to expand China’s trade networks, diplomatic relations, and cultural influence, and his use of advanced navigational tools helped to pave the way for future maritime exploration and discovery.

style compass in ancient China

The compass in ancient China had various styles, including the floating compass, the nail compass, the bowl compass, and the suspended compass. These compasses were used for different purposes, such as navigation, geomancy, and military tactics. The design and construction of the compass evolved over time, with improvements made by different scientists and inventors.

sinan compass

The Sinan compass was made by carving a spoon-shaped piece of the natural magnet into a balanced and symmetrical shape with a handle pointing towards the south pole. It was placed on a smooth circular plate with twenty-four directions marked on it, based on the traditional Chinese system of stems and branches. The Sinan compass was the result of careful observation and experimentation with natural magnetic phenomena and was a practical application of the understanding of magnetic polarity. However, the Sinan compass had several drawbacks, including the difficulty of finding natural magnets, the tendency to demagnetize easily, and the need for a perfectly smooth surface for it to rotate freely. Its size and weight also made it inconvenient to carry around. Despite these limitations, the Sinan compass was an important step in the development of compass technology in ancient China, paving the way for more sophisticated and versatile compasses in the future.

Luo Pan Compass

A luopan, also known as a feng shui compass, is a tool used in feng shui for detecting qi. It is a commonly used operational tool in the theory of qi. The luopan consists mainly of a magnetic needle located in the centre of a series of concentric circles, with each circle representing the understanding of the ancient Chinese people of a certain level of information in the universe.

The ancient Chinese believed that the human aura is controlled by the aura of the universe, and harmony between humans and the universe is auspicious, while disharmony is inauspicious. Therefore, based on their experiences, they placed various levels of information about the universe on the luopan, such as the constellations in the sky, everything in the world represented by the Five Elements, and the heavenly stems and earthly branches. A feng shui master uses the rotation of the magnetic needle to find the most suitable direction or timing for specific individuals or events. Although the concept of “magnetic field” is not mentioned in feng shui, the combination of direction, orientation, and interval in each circle on the luopan implies the law of the “magnetic field.”

Guide to Fish (south-pointing fish)

The “south-pointing fish,” also known as the “compass fish, described in Guide to Fish, was first recorded in the Jin Dynasty of China in the 4th century AD. It was made by heating thin iron sheets cut into the shape of a fish in the Earth’s magnetic field and could float on the water with its head pointing south. The south-pointing fish was more flexible than the Sinan compass but had weaker magnetic properties. It was recorded in the “Wujing Zongyao” and was used in military applications during the early Northern Song Dynasty. Like the Sinan compass, it was an instrument used in ancient China to indicate direction and discern orientation.

A water compass in ancient China

The water compass, also known as the “divine water spoon,” was an ancient Chinese compass that used water as its main component. It was used during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) and was based on the principle of the magnetic needle. The compass consisted of a wooden platform with a bowl of water at its centre. A small, spoon-shaped lodestone was placed on the surface of the water, which would align with the Earth’s magnetic field, indicating the south. The water compass was primarily used by Chinese fortune-tellers and geomancers to determine the proper orientation of buildings and to locate favourable sites for tombs or other structures. While the water compass was eventually replaced by the magnetic compass, it was a significant advancement in the development of navigational tools in ancient China.

This type of navigational instrument is more sensitive than the Sinan, and it is the earliest compass used for navigation. Ancient Chinese ships were equipped with a water compass, and by the Ming Dynasty, the various technical indicators of the compass were quite complete. Zheng He’s treasure ship, which sailed to the west, was equipped with a water compass. Guided by the water compass, Zheng He’s fleet accomplished several magnificent voyages to the west.

south-pointing chariot

The south-pointing chariot is an ancient Chinese mechanical device that used a differential gear system to maintain a consistent orientation regardless of changes in direction or terrain. It was designed to always point towards the south, allowing travelers to navigate without getting lost. The chariot was invented during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC) and became more sophisticated during the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). It was used for military purposes as well as for astronomical and calendrical observations. The south-pointing chariot is considered a remarkable achievement in ancient Chinese technology and engineering.

The South-pointing The chariot, also known as the Sinan chariot, is a device used in ancient China to indicate direction and as an imperial ceremonial vehicle. Unlike the compass, which utilises the Earth’s magnetic field, the south-pointing Chariot does not rely on magnetism. It is a simple mechanical device that uses a gear transmission to indicate direction. The principle is that the chariot is powered by human force to drive the two wheels, which in turn drive the wooden gears inside the chariot to transfer the differential between the two wheels when turning. This then drives the wooden figure on the chariot to point in the opposite direction with the same angle as the turn, indicating the direction of travel. Regardless of the direction in which the chariot turns, the wooden figure’s hand always points in the direction set when the chariot was first set up; “the cart may turn, but the hand always points south”.

When did the compass come to Europe?

The exact date of when the compass first arrived in Europe is uncertain, but it is believed to have been introduced in the High Middle Ages, around the 12th century. The earliest written reference to the compass in Europe dates back to 1190, in a letter written by Alexander Neckam, an English monk and natural philosopher. However, it is possible that the compass was known to Europeans even earlier through contact with the Islamic world or during the Crusades.

Who brought the compass to Europe?

It is believed that the compass was brought to Europe by Italian explorer and merchant Marco Polo, who encountered the device during his travels to China in the late 13th century. However, there is also evidence that suggests that the compass may have been introduced to Europe earlier through Arab traders, who had acquired knowledge of the device from their interactions with the Chinese. Regardless of its exact origins, the compass played a significant role in transforming navigation and exploration in Europe and ultimately had a profound impact on the world.

How did the compass change the world?

The invention of the compass in ancient China had a profound impact on the world. It revolutionized navigation and exploration by allowing sailors to determine their direction and navigate accurately, even when out of sight of land. This greatly expanded the reach of sea travel and trade, leading to increased contact and exchange between different cultures and civilizations.

The compass also played a crucial role in the Age of Discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries, enabling European explorers to undertake long and risky voyages of discovery across the seas. This, in turn, led to the colonisation of new lands, the establishment of new trade routes, and the spread of European influence across the globe.

Beyond navigation and exploration, the compass also had a significant impact on science and technology, providing a better understanding of the Earth’s magnetic field and leading to the development of new instruments such as the sextant and the telescope.

Overall, the compass changed the world by facilitating travel and trade, expanding knowledge, and connecting people and cultures across great distances.

Why does the compass needle show deflection?

The compass needle shows deflection because of the Earth’s magnetic field. The Earth has a magnetic field with a north and south pole. When a compass is placed near a magnet, the magnet’s field will influence the needle in the compass, causing it to align with the magnetic field. The needle will always point towards the Earth’s magnetic north pole. However, due to the Earth’s magnetic field being tilted at an angle to the Earth’s axis of rotation, the needle will not point directly to true north but will show some deflection. Additionally, local magnetic anomalies, such as large deposits of iron ore or other magnetic minerals, can also cause deflection in the compass needle.

Chinese compass vs. Viking compass

The Chinese compass and the Viking compass, also known as the sunstone, are two ancient navigation tools that have played significant roles in their respective cultures. While both compasses served the same purpose of providing direction, they differ in their construction, mechanism, and accuracy.

The Chinese compass, also known as the magnetic compass, was invented during the Han dynasty in China around the 2nd century BC. It consisted of a magnetized iron needle that aligned itself with the Earth’s magnetic field, indicating the north-south axis. The needle was mounted on a circular plate that was divided into 24 directions, each represented by a Chinese character. The Chinese compass revolutionized navigation and allowed sailors to navigate with more precision and accuracy, thus facilitating trade and exploration.

On the other hand, the Viking compass, or sunstone, was used by Norse sailors during the Viking Age, from the 8th to the 11th centuries. The sunstone was a piece of crystal, such as calcite, that was believed to be able to detect the polarisation of sunlight, even in cloudy or foggy weather. The sailors would hold the sunstone up to the sky and rotate it until it matched the polarisation pattern of the sun; then, the direction of the sunstone’s shadow would indicate the position of the sun, allowing sailors to determine their direction.

In terms of accuracy, the Chinese compass was a more reliable navigation tool than the Viking sunstone. The Chinese compass was not affected by the weather conditions and could be used day or night, while the Viking sunstone was dependent on clear skies and strong sunlight. The Chinese compass was also more precise, as it could indicate the exact direction, while the Viking sunstone could only determine the general direction based on the position of the sun.

In conclusion, while both the Chinese compass and Viking sunstone served the same purpose of providing direction, they were different in their construction, mechanism, and accuracy. The Chinese compass was more reliable and precise, while the Viking sunstone was more dependent on weather conditions and less precise. Both navigation tools played important roles in the exploration and trade of their respective cultures and contributed to the development of navigation technology.

Conclusion

Without the development of the compass, we would be geographically isolated in many ways, so they are very important in man’s history. They were first developed in China during the Song dynasty for worship, geomancy, and fortune-telling, but have become an essential aspect of our lives once their designs were improved for navigation.

bookmarked!!, I love your website!

Pingback: Google