China is known for its teas and the medicinal properties they have. But, although their alcoholic drinks aren’t as popular, it doesn’t mean that they are non-existent. Drinking alcohol in China is a big deal. Alcoholic drinks in China are normally taken on special occasions like over a business deal that’s been successfully closed or a wedding. On such occasions, the drinks are usually used to make toasts.

Just as there are rules and culture around drinking tea in China, there is also a drinking culture when it comes to alcoholic drinks. Some important rules are that you should drink at the same pace as everyone else and while toasting your glass should be lower than that of the person you’re toasting.

There are several alcoholic drink options in China. In this post, we will be looking at the common types of alcohol in China. From the list, we will also look at what their most popular alcoholic drink is.

What Alcoholic Drinks Do Chinese Drink?

China has a rich and diverse drinking culture, and there are several traditional alcoholic beverages that are popular in Chinese cuisine and social gatherings. Here are some of the alcoholic drinks commonly consumed in China:

Baijiu: Baijiu is a strong distilled liquor and is considered China’s national drink. It is typically made from fermented sorghum, rice, wheat, or other grains. Baijiu has a high alcohol content, often ranging from 40% to 60% or even higher. It is usually consumed neat or used in traditional toasts during festive occasions and business banquets.

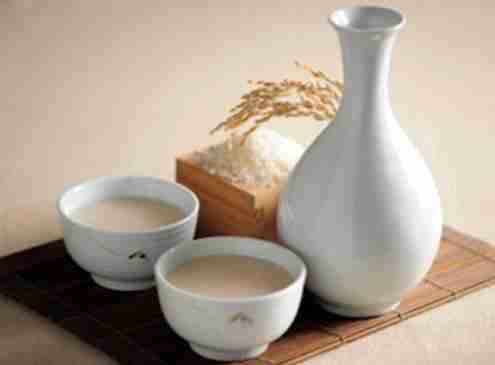

Rice Wine: Rice wine, also known as “mi jiu” or “huang jiu,” is a traditional Chinese alcoholic beverage made from fermented glutinous rice. It has a moderate alcohol content, usually around 15% to 20%. Rice wine is commonly consumed during meals and is also used in cooking to enhance flavors in various dishes.

Huangjiu: Huangjiu, also referred to as “yellow wine,” is another type of traditional Chinese rice wine. It is made from fermented rice, water, and a starter culture. Huangjiu has a sweet and mellow taste and is often aged for several years to develop its flavors. It is commonly consumed as a celebratory drink during festivals and special occasions.

Beer: Beer has gained popularity in China over the years, and both domestic and international beer brands are widely available. Chinese beers range from lighter lagers to darker and stronger varieties. Beer is commonly enjoyed in social gatherings, bars, and restaurants, particularly during hot summers or while watching sports events.

Herbal Liquors: China is also known for various herbal liquors, which are often made by steeping herbs, roots, and other ingredients in alcohol. These herbal liquors, such as Maotai and Wuliangye, have distinct flavors and are believed to have medicinal properties. They are commonly served as digestifs and are enjoyed in moderation.

Fruit Wines: China has a long tradition of making fruit wines, utilizing fruits such as plum, lychee, peach, and various berries. These fruit wines can have different levels of sweetness and are often consumed as a refreshing beverage or used in cooking.

It’s worth noting that the drinking culture in China varies across different regions, with local specialties and preferences. Additionally, imported wines, spirits, and cocktails have also gained popularity in urban areas and among younger generations.

what is traditional Chinese alcohol?

Traditional Chinese alcohol refers to a variety of alcoholic beverages that have been produced and consumed in China for centuries. These beverages are deeply rooted in Chinese culture and have played significant roles in social gatherings, ceremonies, and traditional medicine. Here are some examples of traditional Chinese alcohols:

Baijiu: Baijiu is considered the most traditional and iconic Chinese alcohol. It is a strong distilled liquor typically made from grains like sorghum, rice, wheat, or corn. Baijiu has a high alcohol content, ranging from 40% to 60% or even higher. It is known for its potent aroma and distinct flavor profiles, which can vary depending on the production methods and regional styles. Baijiu is often consumed during special occasions and business banquets.

Huangjiu: Huangjiu, also known as “yellow wine,” is a traditional Chinese rice wine that dates back thousands of years. It is made from fermented rice, water, and a starter culture, often incorporating traditional fermentation techniques. Huangjiu has a sweet and mellow taste, and its flavor develops with aging. It is commonly enjoyed during festivals and important family celebrations.

Maotai: Maotai is a famous type of baijiu that originated from Maotai Town in Guizhou province. It is highly regarded as one of the finest and most prestigious baijiu brands in China. Maotai has a distinct aroma and a strong, fiery taste. It is often associated with formal banquets and gift-giving on special occasions.

Shaoxing Wine: Shaoxing wine, named after the city of Shaoxing in Zhejiang province, is a type of fermented rice wine. It has a rich history and is commonly used in Chinese cooking to enhance flavors in various dishes, particularly in braised and stewed recipes. Shaoxing wine has a slightly sweet and nutty flavor and is also enjoyed as a beverage on its own.

Medicinal Wines: Traditional Chinese medicine incorporates the use of medicinal wines, known as “yao jiu.” These wines are made by infusing herbs, roots, and other botanical ingredients in alcohol. They are believed to have therapeutic properties and are consumed in moderation for their perceived health benefits.

These traditional Chinese alcohols reflect the country’s long-standing brewing and distillation practices, and they continue to hold cultural significance in Chinese society. They are often associated with hospitality, celebrations, and the preservation of age-old customs and traditions.

what is Chinese alcohol called?

The general term for alcohol in Chinese is “jiǔ” . This term encompasses various types of alcoholic beverages, including both traditional Chinese alcohols and international drinks. However, when specifically referring to the traditional Chinese alcohol, the most well-known term is “báijiǔ”, which translates to “white alcohol” or “clear liquor.” Baijiu is the most popular and widely consumed Chinese liquor and is considered the national spirit of China. It is known for its strong and distinctive flavors and is often associated with formal banquets, celebrations, and cultural traditions.

alcohol:

Qionglu, Yaojiang, Xiangyi, Qiongjiang, Huangjiao, Xuanli – Nectar of Qiong, Jade Milk, Fragrant Ants, Yellow Beauty, Mysterious Elixir

Jinbo, Yuyou, Yucu, Yuyi, Yupai, Yujiu – Golden Waves, Jade Companion, Jade Larva, Jade Ants, Jade Lees, Jade Wine

Yuyun, Yuxun, Yuye, Yuyejinbo, Yuyeqiongjiang, Yurenbei – Jade Nectar, Jade Paste, Jade Drips, Jade Liquid Golden Waves, Jade Liquid Qiongjiang, Cup of Jade Person

Yujiang, Yugao, Yuli, Yuxidong, Yudongxi, Yuzun – Jade Liquor, Jade Marrow, Fragrant Brew, Fragrant Ants, Fragrant Lees, Fragrant Lees, Spring Vessel, Fragrant Liquor, Spring Overflow, Spring Lees, Spring Must, Spring Lees, Spring Wine

Yushang, Yulian, Yusui, Fanglu, Fangyi, Fanglao, Fangxu – Jade Goblet, Jade Wine, Jade Marrow, Fragrant Fermentation, Fragrant Ants, Fragrant Liquor, Fragrant Lees

Fangzun, Fangli, Chunang, Chunlu, Chunpei, Chunao, Chunyun – Fragrant Jar, Fragrant Wine, Spring Brim, Spring Fermentation, Spring Lees, Spring Lees, Spring Wine, Spring Ants, Spring Brewing, Aged Spring, Fine Wine, Fermented Rice Wine, Fragrant Lees

Chunli, Chunyi, Chunniang, Laochun, Zhi Jiu, Xun, Xiangqu – Spring Liquor, Spring Ants, Spring Brewing, Old Spring, Fine Wine, Fermented Rice Wine, Fragrant Lees, Fragrant Wine

Xianglao, Luobo, Pei, Lu, Lu Xun, Long, Ganlao, Ganli – Fragrant Lees, Fermented Rice Wine, Lees Waves, Lees, Fermented Rice Wine, Lees, Sweet Fermented Rice Wine, Sweet Liquor

Dukang, Bai Duo, Zhongshan, Yunye, Shixun, Kuangyao, Huoquan – Dukang, Fallen White, Zhongshan, Cloud Liquid, Ten Days, Mad Medicine, Disaster Spring

drinking alcohol/Chinese alcoholic drinks names:

Xianbei – Sipping from the cup

Xianshang – Raising the goblet

Ruanbao – Drinking to satisfaction

Beishao – Sipping from the cup and the ladle

Fubai Jubai – Floating white and lifting white

Hongyin – Downing drinks

Niuyin – Drinking like a cow

Zongjiu – Drinking excessively

Shangzhuo – Toasting and pouring

Gongzhuo – Toasting and pouring with a goblet

what are Chinese alcohol made of?

Chinese alcoholic beverages are made from a wide range of grain and starch-based products. The sources of raw materials are diverse. There are three main categories based on the source:

Starch-based: This includes ingredients like sorghum, corn, and sweet potatoes, which are commonly used as the primary raw materials.

Sugar-based: This includes ingredients like sugar beets and sugarcane, which are used as supplementary raw materials.

Fiber-based: This includes materials like rice straw and wood chips, which are typically used for industrial fuel production. These materials undergo chemical treatment to convert the fibers into sugar before the fermentation and distillation process.

With the rapid development of modern brewing technology, the dominance of sorghum as a grain for alcohol production has started to change. Currently, corn and rice have become the preferred materials for producing distilled spirits. Different grains used in alcohol production yield different characteristics. For example, wheat produces a rough texture, glutinous rice produces a soft and delicate texture, polished rice produces a clean flavor, corn produces a sweet taste, and sorghum produces a fragrant aroma.

Certain grains pose challenges in alcohol production due to their composition. Wheat, barley, and legumes have high protein content, which can lead to excessive growth of bacteria during fermentation, resulting in unpleasant flavors. Glutinous rice and buckwheat have high stickiness, which can reduce the permeability of the fermentation mash and decrease fermentation efficiency. Rice, due to its high fat and cellulose content, can also affect the taste of the resulting liquor. Corn, on the other hand, tends to have a higher sweetness due to its high phytic acid content, and its higher fat content can result in off-flavors.

Other ingredients such as sweet potatoes, potatoes, and cassava have low protein and fat content but high pectin content, which can promote the growth of bacteria and affect the taste.

Sorghum stands out as an ideal material for brewing due to its high starch content, balanced proportions of fat and protein, and favorable fermentation that produces pleasant aromas without generating off-flavors.

In ancient times, the cultivation of grains served the purpose of making alcohol rather than being consumed as food for sustenance. As a result, the culture of Chinese spirits flourished in ancient times. Various grains such as sorghum, rice, glutinous rice, peas, corn, wheat, barley, and buckwheat, as well as tubers like sweet potatoes and potatoes, were used as raw materials for brewing, expanding the variety of available ingredients.

The essential condition for brewing is the raw material. Historical records and archaeological findings indicate that in the pre-Qin period, alcohol was primarily brewed using grains and occasionally with fruits and vegetables. The demand for specific raw materials for brewing can be seen in ancient texts. For example, “Li Ji” mentions “rice and sorghum must be provided,” and “Zhou Li” records: “The king’s offerings include the six grains, the food includes the six animals, and the drinks include the six types of clear liquors.”

Archaeological findings have revealed pottery jars with white sediment in Zhengzhou Shangcheng, indicating the use of grains or fruits for brewing. In another excavation at Shang Dynasty’s Luo Mountain Tianhu cemetery in Henan, a well-sealed bronze you vessel was discovered with a liquid that emitted a fragrance. Chromatographic analysis showed the presence of ethyl formate, indicating the production of a richly aromatic liquor.

Archaeologists frequently uncover ancient liquor during excavations of pre-Qin sites, indicating that people in ancient times brewed alcohol using various grains and fruits. This suggests a relatively diverse lifestyle during that period.

What Alcoholic Drinks Do Chinese Drink?

Alcoholic drinks vary in China. There are many options to choose from including different types of beers, wines, cocktails, and liquors like Baijiu. The following are some of the common types of liquor you’re likely to come across in China:

Rice Wine.

This type of alcohol exists in large varieties in different parts of Asia, but it is said to have originated from China. Although it’s referred to as wine, the techniques used in making it resemble brewing more.

Rice wine is made from steamed rice that’s mashed and mixed with yeast (starter). During the making process, the starch in the rice first converts into sugar. From there the presence of the starter turn the sugar into liquor. The taste of rice wine varies based on how it was produced but generally, it’s sweet.

Mijiu.

In Taiwan, this drink is called michiu, although universally it refers to basic Chinese rice wine. It is made from glutinous rice and is considered the first variety of rice wine before others came up around Asia. Normally it’s heated before drinking, although this type of wine is mostly used in making different cuisines. The variety made for cooking is normally slightly salted to add flavor to the food. The alcohol percentage ranges from 12-20%.

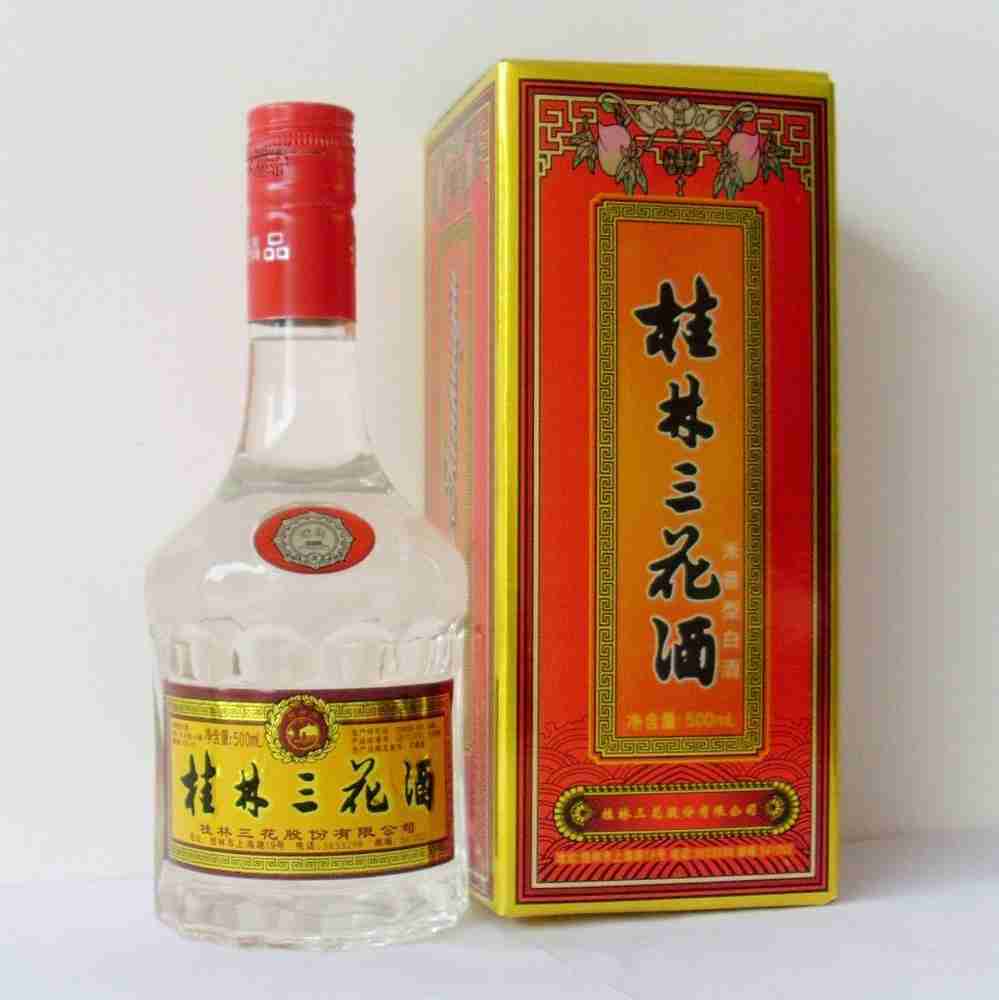

Sanhuajiu.

This type of alcohol comes from Guilin in China but is said to have originated during the Song Dynasty. It’s considered an expensive variety of rice liquor made from the pristine waters of Li River, mixed with high-quality steamed rice and a starter. The starter used in this particular drink is normally said to contain a subtle herbal taste and carries medicinal properties. The mixture is then distilled to produce a clear and colorless spirit. It has a sweet aftertaste with a vague herbaceous aroma. To age the spirit, it is normally stored in clay pots and left in the Guilin caves that offer the best cool suitable climate.

Baijiu.

This drink is considered the national Chinese drink and an important part of its culture. There is no special occasion that passes without a toast of the drink. It is a clear spirit made from distilling fermented grains. The grains vary from rice, sticky rice, sorghum, corn, and wheat. Based on the products used, Baijiu is in many varieties, but overall, it has a high-quality complex full-bodied flavor. It’s normally packaged as containing 50%ABV and categorized based on the strength of its aroma. That is light, strong, rice or sauce baijiu.

Chhaang.

This drink is most famous in Nepal and Tibet in China. It’s made from either rice, barley, or millet. It has a slightly gritty texture and appears cloudy and milky white. Most people will describe its flavor as tart and sweet. The drink is made by cooking the grains, chilling them, and mixing in yeast. The mixture is then left to ferment for some days and then mixed with water. The resulting drink has low alcoholic content and may sometimes be frizzy depending on how long it’s fermented.

Erguotou.

This is a potent and clear type of Baijiu with 60%ABV, normally enjoyed in small amounts as a social drink. It originated in the 17th century and is strongly associated with Beijing and other parts of North-East China. This strong spirit is made through the double distillation of fermented sorghum.

Shaoxing Wine.

Shaoxing Wine is another type of rice wine that’s amber and clear with 18%ABV. It’s especially popular in Zhejiang province and made from brown glutinous rice that’s been aged for over decades. It’s normally used in cuisines as flavorings for marinades and sauces or stir-fried or braised dishes.

Maotai Baijiu.

This is a variety of Baijiu is the most popular kind made from fermented sorghum that’s distilled seven times throughout the year. It’s then stored and aged in earthware vessels before it’s blended. The resulting drink is pure and crisp and praised for its complex flavor. Traditionally, you’re meant to serve them in special tulip-shaped glasses at room temperature and enjoy them on special occasions. They also make great a special gift.

Xifengjiu.

This variety of baijiu is made using the natural underground water from Shaanxi province. It is said to have originated from Feng Xiang where phoenixes would fly from hence its name. Unlike other baijiu varieties, this one has a combined aroma of both light and strong baijiu with a lingering finish. The strong drink can be made from fermented peas, sorghum, barley, and wheat.

What Is the Most Popular Alcoholic Drink in China?

The most popular alcoholic drink consumed in China is Baijiu, which is why it is considered the Chinese National drink. It is always present for every special occasion in China. Although its fame hasn’t made it out of the country, it is the top-selling type of alcohol there.

It is traditional alcohol that has been produced for over 5o centuries in China. It can be made from distilling a large variety of grains, from rice, sorghum, and peas, to barley, corn, and wheat. Its alcoholic content will vary from30-60%ABV. The different varieties are categorized based on the varieties we’ve already mentioned. The most popular variety is Maotai and the most potent is Erguotou.

how to make Chinese alcohol?

Making Chinese alcohol, particularly traditional Chinese liquor (baijiu), involves a specific process. Here is a step-by-step guide on how to make Chinese alcohol:

Select the Raw Materials: The main ingredient for Chinese liquor is typically sorghum, but other grains like rice, wheat, or corn can also be used. Choose high-quality grains free from impurities.

Steaming or Cooking: If using grains like sorghum or rice, they are usually steamed or cooked to gelatinize the starches. This process makes it easier for enzymes to convert the starches into fermentable sugars.

Prepare Qu (Starter Culture): Qu is a mixture of beneficial molds, yeasts, and bacteria that is used to initiate fermentation and contribute to the flavor profile of the liquor. Qu can be obtained from a previous batch of fermented grains or purchased from specialized suppliers.

Mixing the Ingredients: Mix the steamed or cooked grains with water and allow them to cool to a suitable temperature for fermentation. The ratio of grains to water depends on the desired alcohol content and the specific recipe.

Inoculation with Qu: Add the qu starter culture to the mixture of grains and water. Thoroughly mix to ensure even distribution of the starter culture.

Fermentation: Transfer the mixture to fermentation vessels, such as earthenware jars or stainless steel tanks. The vessels should be sealed but allow for the release of carbon dioxide produced during fermentation. Fermentation typically takes place in a controlled environment at a specific temperature. The duration of fermentation can vary from days to several weeks, depending on the desired flavor and alcohol content.

Distillation: After fermentation, the fermented mash is ready for distillation. Distillation separates the alcohol from the liquid by heating the mash and collecting the vapor. Traditional Chinese liquor is typically distilled using a pot still. Distillation occurs in multiple stages, with the collected alcohol being re-distilled to increase purity. Different fractions of the distillate are collected to achieve the desired flavor profile.

Aging: Some Chinese liquors undergo an aging process to further develop their flavors. The distilled liquor is stored in ceramic jars or wooden barrels for a period, allowing it to mature and mellow. Aging times can range from several months to many years.

It’s important to note that making Chinese alcohol, especially traditional Chinese liquor, requires specialized knowledge, equipment, and expertise. The process described here provides a general overview, but variations and specific techniques can differ depending on the type of Chinese alcohol being produced. It is also essential to comply with safety and legal regulations governing alcohol production in your region.

make alcohol in ancient china

As early as over 3,000 years ago, ancient Chinese people discovered a material called “jiu qu” (fermentation starter) that could produce sweet and aromatic alcohol with a long-lasting aftertaste. For thousands of years, jiu qu has been the secret to brewing Chinese liquor. However, not many people today truly understand how our ancestors made such fine wines. Even Xiaochi Net’s Xiao 7, who is a wine lover, enjoys a small sip of vinegar before bedtime, and Xiao 7’s family is also fond of alcohol. Their grandmother is a loyal fan of rice wine.

In March 1999, the archaeological excavation of Shuijingfang revealed the complete process of ancient Chinese wine production.

The first step in making wine for the Chinese was to steam or cook the grains. The steamed grains were mixed with jiu qu, and after cooking, they became more conducive to fermentation. In the traditional process, the semi-cooked grains were spread on the ground, which was the second step of brewing—stirring, adding ingredients, piling up, and initiating the initial fermentation. The ground used for drying the grains had a specific name, called “liang tang” (drying platform). The Shuijingfang site excavated three liang tangs that overlapped each other. The soil pit next to the liang tangs was the wine cellar site, resembling giant wine vats buried in the ground. Shuijingfang uncovered eight wine cellar pits, where the inner walls and bottoms were coated with pure yellow clay, with a thickness ranging from 8 to 25 centimeters.

The wine cellar was the third step of wine production, where the raw materials underwent further fermentation.

The fermented mash in the cellar still had a low alcohol content, so it required further distillation and condensation to obtain high alcohol content baijiu. The traditional process used a distillation apparatus known as “tian guo” (celestial pot) to complete this step.

During the excavation, archaeologists discovered a peculiar circular structure from the Qing Dynasty, which, at first glance, resembled a well. After investigation, it was confirmed as the earliest physical evidence of distillation in China. In those days, a large celestial pot was placed on the pedestal, with two layers: the lower pot contained the fermented mash, and the upper pot contained cold water. The firewood burned vigorously on the pedestal, steaming the fermented mash. The alcohol-containing gas was cooled by the cold water on top, condensing into liquid and flowing out through the pipes. This was the process of distillation.

Based on this, it was inferred that during the Qing Dynasty, the production here was indeed for distillation, and the technology was already very close to modern brewing techniques. Experts analyzed the microorganisms in several old fermentation pits at Shuijingfang and isolated red yeast and koji mold. The archaeological evidence from Shuijingfang confirmed that China had a mature distillation technique as early as the end of the Yuan Dynasty and the beginning of the Ming Dynasty.

Chinese distilled liquor is categorized into different types, such as strong aroma, light aroma, and sauce aroma. The liquor produced by Shuijingfang belongs to the strong aroma type, which is the most widely distributed type of Chinese distilled liquor. Its most distinctive characteristic in brewing techniques is the use of mud pits, making it a unique category in Chinese brewing techniques. Its place of origin is the Chengdu Plain and Sichuan Basin, where excellent strong aroma liquor can be produced.

Due to the limited area currently excavated, the deeper layers below the third level have not been extensively explored. Therefore, there may still be earlier relics and sites buried beneath the site. The truth about the abandonment and use of different historical layers may be revealed in future excavations, providing a more reasonable explanation.

Making Rice Wine in Winter:

First, soak the rice in water for about four to five hours, then steam it. After steaming, spread it out to cool. Crush the jiu qu and layer it with the rice in a container, one layer of rice followed by one layer of jiu qu (the amount of jiu qu will be indicated when you purchase it). After compacting, cover it with a cotton quilt and let it sit for a day. Hairs will start to grow on the surface. Water the hairs with sweet wine to disperse them fully. After another day, the sweet wine will be ready.

Making Grape Wine in Summer:

Soak the grapes in a weak saltwater solution for an hour, then drain the water. Crush the grapes one by one and add sugar in a ratio of 10:1 (adjust the sugar amount according to personal preference). Place the crushed grapes and sugar in a large-mouthed bottle. Let it sit for twenty days, and it will naturally ferment into 100% grape wine. The grape residue on top, sediment at the bottom, and the middle part are the wine. Use a thin tube to extract the middle part and transfer it to another bottle for consumption. The color and taste will be the same as commercially available grape wine—aromatic and transparent.

Red Grape Wine:

Method:

Select good quality red grapes and wash them with clean water. Then, use a clean cloth or sterilized tissue to dry the surface of the grapes (make sure they are completely dry).

Choose a larger container and place the dried grapes in it.

Add an appropriate amount of rock sugar (must use rock sugar). The amount of sugar can be adjusted according to personal taste.

Seal the container tightly. Store it at room temperature, preferably in a dark place. After one week, when there is grape juice, it can be consumed.

styles Chinese alcoholic

Chinese alcoholic beverages encompass a wide range of styles and types. Here are some popular styles of Chinese alcohol:

Baijiu : Baijiu is the most famous and widely consumed Chinese liquor. It is a strong distilled spirit typically made from grains such as sorghum, rice, wheat, or corn. Baijiu can have a variety of flavors, including strong aroma, light aroma, sauce aroma, and rice aroma. Each style has its unique characteristics and production methods.

Huangjiu : Huangjiu, also known as Chinese rice wine, is a traditional fermented alcoholic beverage. It is made from rice, water, and a starter culture called jiuqu. Huangjiu can be categorized into several types based on the production method and aging process. Some popular types include Shaoxing rice wine, Mijiu, and Jiafanjiu.

Maotai : Maotai is a renowned variety of baijiu produced in the town of Maotai in Guizhou province. It is considered one of the highest quality and most expensive baijiu brands in China. Maotai has a distinct aroma and is often associated with formal occasions and special celebrations.

Erguotou : Erguotou is a type of baijiu that originated in Beijing. It is a strong liquor with a high alcohol content and a mellow flavor. Erguotou is often enjoyed as a popular choice for everyday drinking and is commonly found in Beijing’s local bars and restaurants.

Fenjiu : Fenjiu is a type of baijiu produced in Shanxi province. It has a history dating back more than 1,000 years. Fenjiu is known for its mild aroma and smooth taste. It is often served at banquets and special occasions in northern China.

Wuliangye : Wuliangye is a famous brand of baijiu originating from Yibin in Sichuan province. It is made from a blend of five different grains, including sorghum, rice, corn, wheat, and barley. Wuliangye is highly regarded for its rich aroma and complex flavor profile.

These are just a few examples of the diverse styles of Chinese alcohol. Each region in China may have its own unique traditional alcoholic beverages, often with distinct production methods and flavor profiles.

what is the most popular alcoholic drink in China?

The most popular alcoholic drink in China is baijiu. Baijiu is a strong distilled spirit that has been a traditional Chinese liquor for centuries. It is widely consumed and deeply ingrained in Chinese culture. Baijiu is produced throughout the country, and its popularity extends to various social gatherings, business meetings, and celebratory occasions.

Baijiu holds a significant market share in the Chinese alcohol industry, accounting for a substantial portion of alcohol sales in the country. It is enjoyed by people of different ages and backgrounds. While there are various styles and brands of baijiu available, the strong aroma (sometimes referred to as “strong fragrance” or “strong aroma”) and light aroma baijiu are the most commonly consumed types.

It’s worth noting that the popularity of specific alcoholic beverages can vary among different regions and demographics within China. Regional preferences and cultural factors may influence the drink choices of individuals in different parts of the country.

history of alcohol in China

China has a 5,000-year history of civilization, and the history of alcohol spans approximately 4,000 years. From the initial murky and tasteless turbid wine to the clear and rich baijiu we have today, the Chinese people have created a historical legacy in the realm of alcohol.

Birth of Alcohol:

In the early years of the Xia Dynasty, Yi Di used mulberry leaves to ferment rice into a drink called “jiu,” which was a type of rice wine offered as a tribute to Yu the Great, the legendary flood-control hero of ancient China. Unfortunately, after tasting the drink, Yu the Great did not appreciate its wonders and found it to be intoxicating, concluding that it was not a good thing.

It wasn’t until the reign of Shaokang, the sixth monarch of the Xia Dynasty, that the brewing method for making Shujiu (a type of clear wine made from high-glutinous millet) was created. Shaokang is revered as the “founder of winemaking.” The Shuowen Jiezi, an ancient Chinese dictionary, records: “Shaokang began making Shujiu. Also known as Shaokang, the ruler of the Xia Dynasty.”

Standardizing Wine Etiquette:

After the birth of alcohol, it was primarily used for sacrificial ceremonies. However, during the Shang Dynasty, the custom of drinking alcohol became widespread, and the last ruler of the Shang Dynasty, King Zhou of Shang, even indulged in excessive drinking and debauchery.

Following the downfall of the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou Dynasty learned from this lesson and began to strictly regulate alcohol. Ji Dan, the younger brother of King Wu of Zhou, issued the first alcohol prohibition called the “Jiu Gao” (Proclamation on Alcohol). It clearly defined when one could not drink, when one could drink, and how to drink.

Unfortunately, during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods that followed the collapse of the Western Zhou Dynasty, a decline in ritual and music occurred, and the custom of feasting and drinking among the feudal lords once again prevailed.

Popularization of Winemaking:

The Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties lasted for approximately 1,800 years, during which time the main fermentation agents for winemaking were koji and sprouts. Koji refers to moldy grains, while sprouts refer to moldy sprouted grains. Wine fermented with koji was called “jiu,” while that fermented with sprouts was called “li.”

After the end of the Warring States period and the establishment of the Qin Dynasty, koji fermentation became mainstream, and sprout fermentation gradually faded away due to its low efficiency in winemaking.

With the improvement of winemaking efficiency and the evolution of techniques over thousands of years, winemaking began to spread among the common people during the Qin and Han Dynasties. Many ordinary people made a living by brewing their own private wine. In the Western Han Dynasty, in a place called Qionglai in Sichuan, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, Zhuo Wenjun, eloped with Sima Xiangru because of a poem he wrote called “Phoenix Seeking Phoenix.” To make a living, the couple opened a tavern, with Wenjun selling wine at the counter while Xiangru washed wine utensils in the backyard.

Upgrade of Wine Quality:

During the Three Kingdoms period and the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, wine fermentation techniques underwent a significant upgrade. Jia Sixie, an outstanding agriculturalist during the Northern Wei and Eastern Wei dynasties, wrote a book called “Qimin Yaoshu,” which systematically recorded the brewing process, qu fermentation techniques, and more.

The upgrading of wine quality led to its increased popularity and became a vessel for personal emotions. Wang Xizhi of the Eastern Jin Dynasty famously wrote the first masterpiece of calligraphy, “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” while under the influence of alcohol. The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove also gathered in a bamboo grove to escape political troubles and enjoyed drinking and revelry.

Drinking Culture among the Masses:

During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the culture of taverns thrived, and they were found everywhere. People would gather in taverns for drinking and entertainment after the curfew at night, and drinking games gradually became popular.

The Tang Dynasty reached a peak in terms of widespread drinking culture, as poet Liu Yuxi exclaimed, “There is no one who does not sell wine, and there is nowhere one does not hear music.” Alcohol also inspired countless literary and artistic works. It is estimated that out of the existing over 40,000 Tang poems, nearly 7,000 are related to alcohol, with Du Fu contributing around 300 of them.

During the Song Dynasty, private brewing became highly developed. Su Shi, also known as Su Dongpo, was a master of private brewing and even wrote a book called “The Eastern Slope Wine Classic.” However, the quality of private-brewed wine never matched that of official-brewed wine, but it was cheaper and still enjoyable.

Era of Distilled Spirits:

Before the appearance of distilled spirits, the alcohol consumed by ancient people was primarily rice wine, which was categorized based on alcohol content into high-quality yellow wine, medium-grade green wine, and low-grade turbid wine. With the maturation of brewing techniques, the transition gradually occurred from low-alcohol turbid wine to yellow wine.

The Yuan Dynasty marked the most significant turning point in Chinese alcohol, as it expanded its territory and engaged in exchanges with the West. Distillation methods were introduced, and they combined with grain wine to produce clear and rich distilled spirits, shaking the traditional fermentation-based alcohol industry.

Different periods of distilled spirits:

Before the Song Dynasty, “distilled spirits” referred to the method of heating fermented wine to deactivate and sterilize it.

After the Yuan Dynasty, “distilled spirits” generally referred to distilled wine, including grape spirits and grain spirits.

After the Ming Dynasty, the term “distilled spirits” specifically referred to grain distilled spirits.

Era of Sorghum Liquor:

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, in order to control flooding, the imperial court ordered the widespread cultivation of sorghum. Sorghum, with its strong vitality and resistance, was not suitable for consumption as food but proved to be ideal for producing strong liquor. As a result, the raw material for producing distilled spirits gradually shifted from rice to sorghum.

Although sorghum liquor had already been developed during the Yuan Dynasty, it only became popular during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. However, it did not become the mainstream choice until before the Republic of China era. Traditional rice wine (yellow wine), which had been passed down for thousands of years, was dominant, especially in affluent regions such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, where Huangjiu, Niangjiu, and Zhuangyuanhong were the mainstream rice wines.

Sorghum liquor, on the other hand, gained popularity among the common people in relatively poor regions. Distilled sorghum liquor, with its purified alcohol content, was more stimulating, invigorating, had better warming effects, and was easier to store. It offered high cost-effectiveness.

Era of Baijiu:

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, through the transformation of socialist public ownership, private brewing workshops were all taken over and turned into state-owned enterprises. They were then organized into local distilleries. After decades of development, Chinese baijiu has reached its present state, characterized by “a hundred flowers blooming, a hundred schools of thought contending.”

However, it is important to note the distinction. In ancient times, “baijiu” referred to rice wine. Before modern times, Chinese baijiu had various names based on production methods, appearance, raw materials, or color. It was called huojiu, jiu lu, han jiu, qi jiu, shao jiu, shao dao, bai gan, among others. Among them, “shao jiu” was the most commonly used name.

It was not until the 1950s that grain distillate was defined as baijiu. This term became the standardized industry language after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It should be distinguished from the ancient term for distilled spirits.

did china invent alcohol?

The exact origins of alcohol production are difficult to determine with certainty, as alcoholic beverages have been produced and consumed by various cultures throughout history. However, China has a long history of alcohol production, and it is considered one of the earliest regions where the production of alcoholic beverages was developed.

There is evidence to suggest that early forms of alcohol production existed in China as far back as the Neolithic period, around 7000-6600 BCE. Archaeological discoveries, such as pottery jars with residue consistent with fermented beverages, indicate the presence of early alcoholic drinks in China.

The discovery of a 9,000-year-old site in Jiahu, Henan Province, revealed pottery jars containing a fermented beverage made from rice, honey, and fruit. This finding is significant because it predates the development of agriculture in the region, suggesting that alcohol production may have played a role in the transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled agricultural communities.

China has a rich tradition of brewing various types of alcoholic beverages, including rice wine, millet wine, and sorghum-based spirits. The brewing techniques and technologies in China have been refined and developed over thousands of years, resulting in a diverse range of traditional alcoholic beverages.

While it is challenging to attribute the invention of alcohol to a specific culture or region, China’s long history of alcohol production and its significant contributions to brewing techniques make it an important part of the global history of alcoholic beverages.

who invented ancient Chinese alcohol?

Regarding the question of who invented alcohol in China, there is no definitive answer, but there are several theories:

Heavenly Creation Theory:

Since ancient times, there has been a belief in China that alcohol was created by the “Star of Wine” in the heavens. In ancient poetry, phrases like “Star of Wine” or “Wine Flag” are often used. For example, the famous poet Li Bai wrote in his poem “Drinking Alone under the Moon”: “If Heaven does not love wine, why is the Wine Star in the sky?” Kong Rong, a scholar during the late Eastern Han Dynasty, described himself as someone who always had guests and never ran out of wine in his poem “Drinking with Qin King,” which includes the line “Pouring wine from the dragon’s head, inviting the Wine Star.” In Dou Ping’s “Jiu Pu” (Book of Wine), it is also mentioned that wine is the work of the “Star of Wine.” The discovery and recording of the Wine Flag Star is considered one of the achievements of ancient Chinese astronomy. It demonstrates the rich imagination of our ancestors and proves that wine held a significant place in social and daily life activities at that time.

Monkey Creation Theory:

There are many records in Chinese literature that monkeys can “make” alcohol. Li Rihua, a scholar from the Ming Dynasty, recorded in his writings: “The Huangshan mountains are filled with monkeys. In spring and summer, they collect various flowers and fruits in stone pits, where they ferment and produce alcohol, releasing a fragrant aroma that can be smelled from a hundred steps away. Some woodcutters who live deep in the mountains manage to steal a drink, but they shouldn’t have too much, as excessive consumption will diminish the traces of alcohol, and if discovered, the monkeys will kill them.” These various records indicate that something similar to “alcohol” was discovered in places where monkeys gather. Alcohol is a fermented food product produced by the decomposition of sugars by microorganisms called yeast. Yeast is a widely distributed type of fungus, and in the vast nature, there are various fruits, especially those with higher sugar content, where yeast can easily thrive. Fruits with high sugar content are important food sources for monkeys. When ripe fruits fall down, they naturally undergo fermentation due to the action of yeast on the fruit skin or in the air, resulting in the liquid form of “alcohol.” Monkeys unknowingly “create” alcohol by collecting and storing large quantities of ripe fruits in “stone pits” where the accumulated fruits undergo fermentation and the liquid form of “alcohol” is produced. The fact that monkeys can unintentionally “make” alcohol is logical and reasonable.

Yidi’s Invention Theory:

According to legend, Yidi, during the reign of Emperor Yu of the Xia Dynasty, invented brewing. In the 2nd century BCE, the historical book “The Annals of Lü Buwei” stated, “Yidi made wine.” Liu Xiang’s “Strategies of the Warring States” from the Han Dynasty also mentioned that Yidi, the daughter of Emperor Yu, was appointed to oversee the brewing of wine. After her efforts, she brewed a wine with a good taste and presented it to Emperor Yu for tasting. Emperor Yu enjoyed the wine but believed that excessive drinking could lead to the downfall of future rulers, so he distanced himself from her. This account has been passed down through the ages, and people highly respect Emperor Yu, considering him a principled and enlightened ruler who detested alcohol, while Yidi is depicted as a sycophant. Some scholars believe that brewing alcohol from grains is a complex process and cannot be accomplished by an individual alone. Yidi may have been a skilled brewer or an official overseeing the brewing process. He may have summarized the experiences of his predecessors and improved the brewing methods, ultimately producing high-quality wine. Guo Moruo also holds this view, stating, “It is said that Yidi, a minister under Emperor Yu, began brewing, which refers to wine that is sweeter and stronger than the wine of the primitive society.”

Dukang’s Invention Theory:

Dukang, as recorded in “Records of the Grand Historian,” was a ruler during the Xia Dynasty and is considered the legendary “ancestor of brewing” in ancient China. “Shuowen Jiezi,” a dictionary from the Han Dynasty, states, “Dukang first made grain wine. Also known as Shaokang, he was the ruler of the Xia Dynasty.” Due to Dukang’s skill in brewing, he was revered as the god of wine by future generations, and the brewing industry honored him as the ancestor. In later times, the term “Dukang” became synonymous with alcohol. There is debate about the historical period in which Dukang lived. Online sources mention three possibilities: First, Dukang was a minister during the time of the Yellow Emperor. Second, Dukang was the sixth ruler of the Xia Dynasty, also known as Shaokang. Third, Dukang lived during the Han Dynasty. In the Three Kingdoms period, Cao Cao wrote the famous poem “Short Song Style,” which includes the line, “How can one resolve worries? Only with Dukang.” This line highly praises the wonderful effects of Dukang’s wine. The history of alcohol production in ancient China is a long and significant one, involving contributions from many individuals. However, Dukang represents a certain aspect, and in a sense, the legendary wine god Dukang represents the spirit of civilization, scientific innovation, and originality of ancient Chinese people.

Origin of Distilled Liquor

The earliest form of alcohol in China was Huangjiu, also known as fermented or brewed liquor, which does not involve distillation. It was later followed by the development of distilled liquor, known as Chinese baijiu, which is associated with the invention of distillation equipment. Some believe that distillation was present during the Eastern Han Dynasty since bronze distillation apparatuses existed during that period. Others argue that the term “burnt wine” mentioned in poems by Bai Juyi and other poets refers to distilled liquor. The Song Dynasty’s “Dan Fang Xu Zhi” describes a distillation apparatus called the “mercury pump,” and Zhou Qufei’s “Ling Wai Dai Da” from the Southern Song Dynasty records the utensils used by people in Guangxi for distilling “silver vermilion.” Based on these records, some argue that distilled liquor may have originated during the Song Dynasty. The historical evidence of the appearance of documented baijiu, however, points to the Yuan Dynasty. Li Shizhen wrote in his “Compendium of Materia Medica” during the Ming Dynasty: “Burnt wine is not an ancient method; it was created during the Yuan Dynasty.” Tan Cui’s “Dian Hai Yu Heng Zhi” from the Qing Dynasty states: “The name for burnt wine is Wine Dew, which was introduced to China at the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty. Chinese people drink burnt wine everywhere.”

when was the first Chinese alcohol?

The origin of alcohol in China is believed to date back to the ancient times of the Three Sovereigns, particularly the earliest of them, Fuxi, as mentioned in mythical legends. This is considered credible evidence by the discovery of pottery vessels with the shape of the character “酉” (meaning “to make wine” in ancient context), resembling oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, unearthed from the Banpo Village site near Xi’an, which dates back approximately 7,000 years.

The initial form of alcohol was not intentionally produced but rather discovered unintentionally through the natural fermentation of grains or fruits. Jiang Tong provided a specific explanation, stating that leftover rice was poured in shady and moist areas like mulberry groves, which resulted in starch undergoing saccharification and alcohol fermentation. This account objectively reflects the accumulation and prolonged storage of grains or fruits, which eventually transform into wine. It helps demystify the process of brewing by emphasizing the factual aspects of the transformation of stored food into alcohol.

Therefore, it can be concluded that alcohol in China originated from the natural fermentation of grains and fruits, and the exact inventors or discoverers cannot be attributed to specific individuals but rather to the ancient Chinese people’s observation and experimentation with their environment.

where are the first Chinese alcohol?

Archaeological excavations of the Longshan Culture have provided evidence that specialized utensils for brewing and drinking alcohol existed as early as 2800-2300 BCE. Following the liberation, a wine-drinking site from the Shang Dynasty was discovered in Erli Gang, Zhengzhou, and a relatively intact brewing workshop was found in Taixi Village, Gaocheng County, Hebei Province.

In December 1987, at the Tianhu Shang Dynasty Tomb site in Mangzhang Township, Luoshan, in the southeastern part of Henan Province, the earliest preserved ancient wine in China was discovered. It was contained within a bronze vessel and was well-preserved and sealed.

Please note that while I have provided a translation of the information you provided, it’s important to verify the specific details and accuracy of archaeological findings through scholarly sources.

why did the Chinese invent alcohol?

The invention of alcohol in China was not a deliberate or intentional act, but rather a natural discovery that occurred as a result of the fermentation process. Ancient Chinese civilizations had a deep understanding of agricultural practices, including the cultivation of grains and fruits. Over time, they observed that when certain grains or fruits were left in a moist and warm environment, they would naturally undergo a transformation and produce a fermented liquid.

The early Chinese likely stumbled upon this fermentation process accidentally, perhaps by leaving grains or fruits in containers or in natural environments for an extended period. They would have noticed that the resulting liquid had different properties, such as a distinct taste and intoxicating effects. This discovery of alcohol was significant as it provided a new way to utilize surplus grains and fruits, and it also played a role in religious and social rituals.

It’s important to note that the invention of alcohol was not unique to China, as various cultures around the world independently discovered fermentation and developed their own alcoholic beverages. The invention of alcohol in China was a product of ancient civilizations’ observations and experimentation with natural processes, combined with their agricultural knowledge and practices.

what are the reasons alcohol was invented in china?

The invention of alcohol in China can be attributed to several factors and reasons. Here are some possible reasons why alcohol was invented in China:

Agricultural abundance: China has a long history of agricultural development, with a wide variety of crops cultivated, including grains like rice, millet, and wheat, as well as fruits like grapes and plums. The surplus of these agricultural products provided an opportunity for experimentation and exploration of different ways to utilize the harvest.

Food preservation: In ancient times, fermentation was one of the methods used to preserve food. By fermenting grains or fruits into alcohol, they could be stored for longer periods, providing a valuable food source during times of scarcity or for long journeys.

Medicinal purposes: Traditional Chinese medicine has a rich history and often incorporated the use of herbal remedies and natural substances. Alcohol was believed to have medicinal properties and was used as a component in various herbal preparations for its perceived therapeutic effects.

Cultural and social practices: Alcohol played a significant role in various cultural and social practices in ancient China. It was used in religious ceremonies, ancestor worship, social gatherings, and hospitality. It became an integral part of social interactions, celebrations, and rites of passage.

Exploration and curiosity: Like many other inventions, the discovery of alcohol may have been a result of human curiosity and experimentation. Ancient Chinese civilizations observed natural fermentation processes and experimented with different ingredients and techniques, leading to the development of various alcoholic beverages.

It’s important to note that the invention of alcohol in China was not driven by a single reason but rather a combination of factors influenced by the agricultural practices, cultural beliefs, and the pursuit of culinary and medicinal advancements of ancient Chinese civilizations.

how was ancient Chinese alcohol made?

According to historical records, it is known that the brewing industry was highly developed during the Yin Dynasty (Shang Dynasty). The people of Yin had a strong fondness for alcohol, which also contributed to the advancement of the brewing industry. The excessive drinking habits of the ruling class in the Yin Dynasty were believed to have led to the downfall of the state, as mentioned in the “Shang Shu” (Book of Documents), “Shang Shu” (Book of Wine Decrees), and “Shi” (Poetry) in the “Da Ya” (Great Odes) section.

The inscriptions on the Western Zhou bronze vessel, the “Da Yu Ding,” analyze that the downfall of the Yin Dynasty was due to excessive drinking. Numerous types and quantities of bronze wine vessels from the Yin Dynasty have been excavated, which also serves as evidence of the prevalence of alcohol consumption among the people of the Yin Dynasty, particularly the ruling class. Brewing and its related industries were highly developed during this period.

The brewers in the palace of the Shang Dynasty gradually understood and mastered the principles of brewing and invented the method of using koji (a type of mold) to brew alcohol. According to the analysis of oracle bone inscriptions, the Yin Dynasty primarily used broomcorn millet as the main ingredient and employed “niao” (translated as koji) for the saccharification and fermentation to produce sweet wine called “li” and fragrant wine called “chang.”

The use of “koji” is mentioned in the “Shang Shu” and “Li Ji” (Book of Rites). The “Shang Shu” states, “If you want to make wine, you must use koji.” The term “koji” is explained in the “Shuo Wen Jie Zi” as “wine mother.”

The term “niao” refers to germinated grains that contain saccharifying enzymes, which facilitate the hydrolysis of starch into glucose through chemical changes. Our ancestors used this method to produce maltose (malt sugar) for a long time. During the Yin and Zhou Dynasties, this principle was utilized as the first step in the brewing process. The wine produced using this method was a sweet wine with a light flavor and was no longer produced later on.

“In ancient times, koji was used to make alcohol, and germinated grains were used to make sweet wine. In later generations, people disliked the light flavor of sweet wine, and it eventually fell out of favor, leading to the loss of the germination method.” From an external perspective, koji resembles starch blocks. It mainly consists of filamentous fungi and yeast with high saccharification and fermentation abilities. The use of koji advanced the ancient brewing techniques in China and was a significant achievement in the utilization of microorganisms.

The use of koji acted as a catalyst for both starch saccharification and fermentation, simplifying the brewing process and directly transforming grains into alcohol through chemical changes. This method is now known as “complex fermentation.” The “Zuo Zhuan” also mentions “mai qu” (wheat koji). The discovery of koji was a turning point in the practical observations and summarization of our ancestors, marking a significant milestone in the history of brewing.

Since then, the production of alcohol in China has been closely associated with koji. The improvement of the variety and quality of alcohol in later generations was primarily achieved through the reform and development of alcohol koji production techniques. However, regardless of the improvements, alcohol koji remains an essential part of the brewing process. Archaeological excavations in Shang Dynasty sites have discovered examples of koji, such as a relatively complete brewery found in the Shang site of Taixicun, Gaocheng, Hebei Province.

At this brewery site, a set of brewing utensils was found, including urns, jars, vessels, pots for storing and serving alcohol, large-mouthed jars for storing brewing ingredients, and funnels for pouring the liquid. The “Zhou Li” records, “The king’s food includes the six grains, the meals include the six domesticated animals, and the drinks include the six pure liquids…” The “six pure liquids” refer to the clear wines brewed from rice, broomcorn millet, and glutinous millet, including the lees-based wine.

During the Zhou Dynasty, the people of Zhou, based on the different tastes obtained from brewing with different grains, had accumulated long-term experience and learned to use different grains for brewing. This was an expression of the advancement in brewing techniques. During the Zhou Dynasty, the royal court had specialized officials responsible for brewing, such as the “jiu zheng” (liquor master), “jiang ren” (yeast master), “da qiu” (chief brewer), and “jiu guan” (liquor official). The “Li Ji” provides a comprehensive summary of brewing experiences.

“It is the responsibility of the chief brewer to ensure that the millets and rice are of good quality, the koji is timely, the fire is clean, the water is fragrant, the pottery is of good quality, and the fire temperature is well-controlled. The chief brewer must carefully oversee the use of the six elements without any negligence.” Here, all the aspects that should be considered in the brewing process are mentioned.

The alcohol produced by these methods was divided into three categories: “shi jiu” (ordinary wine), which may be unfiltered regular wine; “xi jiu” (aged wine), which could be aged lees wine; and “qing jiu” (clear wine), which was wine filtered to remove sediment. It is known that during the storage process, alcohol undergoes esterification due to chemical reactions caused by microorganisms, which enhances the aroma of the wine, commonly known as the fact that aged wine becomes more fragrant.

The name “xi jiu” during the Zhou Dynasty indicates that the Zhou people already had the experience of studying and appreciating “aged cellar” wines. In 1974, two wine pots were unearthed from the tomb of the Zhongshan State in the Warring States period in Hebei Province, and the fragrance of the wine still remains to this day. According to preliminary analysis, these wines contain not only alcohol but also more than ten other components such as sugar and fat. They are a type of koji-brewed wine, which is invaluable material evidence for studying the history of brewing industry in China and even the world.

what was alcohol used for in ancient China?

Alcohol played a significant role in the cultural and social life of ancient civilizations, serving as an essential spiritual nourishment. It served various purposes and held multiple meanings, including social interaction, medicinal use, religious rituals, and emotional solace. Let’s explore the cultural value of alcohol in ancient times together!

The Social Role of Alcohol in Ancient Times

Ancient people often said, “A thousand cups of wine are not too many when true friends meet.” This illustrates the importance of alcohol in the social life of ancient people. Alcohol could enhance relationships, eliminate unfamiliarity and alienation, and bring people closer together. Gathered around a table with drinks, friends could freely express themselves, engage in conversations, and find emotional satisfaction. Additionally, in certain ancient countries or ethnic groups, alcohol consumption was an essential part of major diplomatic activities or grand festive celebrations. For example, in feudal China, royal dynasties would host banquets to entertain guests during the New Year or significant holidays, and toasting was an important aspect of etiquette.

The Medicinal Use of Alcohol in Ancient Times

In traditional Chinese medicine, moderate alcohol consumption was believed to have therapeutic effects. Alcohol was thought to regulate the body’s qi and blood, promote blood circulation, and improve overall physical condition. It was also believed to aid digestion and relieve abdominal bloating and indigestion. In ancient times, many doctors and physicians included alcohol as one of the remedies for treating minor ailments such as flu, headaches, and stomach issues. However, it’s important to note that alcohol was only considered a treatment for minor illnesses and should not be misconstrued as a cure for diseases through excessive or long-term alcohol consumption.

The Ritual and Emotional Comforting Role of Alcohol in Ancient Times

Alcohol often played a significant role in various folk religions, traditional ceremonies, and rituals of ancient times. For instance, offering wine to deities was a common practice in ancient Chinese religious activities. Although this practice is gradually being phased out today, its cultural significance cannot be overlooked. Furthermore, alcohol consumption could provide emotional solace. In times of disappointment or distress, people in ancient times would often seek solace by consuming alcohol. The imagery of solitary drinking was also a prevalent theme in ancient poetry, such as Lu You’s “Observing the Pavilion from a Fishing Boat” and Li Bai’s “Drinking Alone under the Moon.” These works passionately depict the emotional expressions and personal emotional transformations that occur during drinking sessions.

Overall, alcohol in ancient times held cultural value as a means of social interaction, a medicinal remedy (in moderation), a component of religious rituals, and a source of emotional solace.

How did the ancient Chinese drink alcohol?

In ancient China, the consumption of alcohol was deeply ingrained in the culture and social life of the people. Here are some ways in which the ancient Chinese drank alcohol:

Drinking Vessels: The ancient Chinese used various types of drinking vessels to consume alcohol. These vessels included pottery or porcelain cups, bowls, and goblets, as well as bronze or silver wine vessels such as jue (a type of wine cup), guang (a tall stemmed cup), or zun (a ritual wine vessel). The choice of drinking vessel often reflected the social status and occasion.

Toasting: Toasting was an important ritual during gatherings and banquets in ancient China. When drinking together, people would raise their cups and make toasts to express goodwill, friendship, or respect. Toasting etiquette and the order of toasts were observed, and it was common for the host or the most respected person to initiate the toasting.

Banquets and Feasts: Banquets and feasts were occasions where alcohol was prominently consumed. These events were not only about the food but also included an abundance of alcoholic beverages. The host would often serve various types of wines and spirits, and guests would enjoy the drinks while engaging in conversations, entertainment, and performances.

Drinking Games: Drinking games were popular during social gatherings in ancient China. These games were designed to add fun and entertainment to the drinking experience. Examples of drinking games included guessing riddles, reciting poetry, or playing musical instruments, with the loser being required to drink a certain amount of alcohol as a penalty.

Ritual and Ceremonial Drinking: Alcohol played a significant role in various rituals and ceremonies in ancient China. It was offered as a libation to deities and ancestors during religious ceremonies and sacrifices. The rituals involved pouring wine into special vessels or cups, followed by prayers and offerings.

Drinking Etiquette: There were specific rules and etiquette associated with drinking in ancient China. Respect for elders and higher-ranking individuals was essential. It was customary to pour drinks for others, especially for guests or superiors, as a sign of hospitality and respect. Politeness, moderation, and maintaining composure while consuming alcohol were highly valued.

It’s important to note that while alcohol was widely consumed in ancient China, excessive drinking and alcohol abuse were not encouraged and were seen as undesirable behavior. Alcohol was regarded as a social lubricant, a means of forging relationships, and a symbol of hospitality, but moderation and adherence to social norms were emphasized.

Ancient drinking etiquette

Ancient drinking etiquette in China consisted of four main steps: “Bai” (salutation), “Ji” (offering), “Qiu” (tasting), and “Zu Jue” (bottoms up). The process involved showing respect by performing a salutation, pouring a small amount of wine on the ground as an offering to express gratitude to the earth’s bounty, tasting the wine and praising its flavor, and finally, drinking the wine in one gulp.

During a banquet, the host would offer wine to the guests (known as “Chou”), and the guests would reciprocate by offering wine to the host (known as “Zuo”). When offering a toast, it was customary to deliver a few words of appreciation or good wishes. Guests could also toast each other (known as “Lu Chou”), and sometimes a specific order would be followed to toast individuals (known as “Xing Jiu”). When offering a toast, both the person making the toast and the recipient would “avoid the seat” and stand up. Typically, three cups of wine were considered an appropriate amount for a toast.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, there were customs of singing songs and composing impromptu verses during drinking banquets. The game of “Tou Hu,” derived from archery rituals, evolved into a form of drinking game. During the Qin and Han dynasties, people composed impromptu verses at banquets, known as “Ji Xi Chang He,” and over time, this practice developed into various drinking games.

The Tang and Song dynasties represented a pinnacle in the development of Chinese game culture, including drinking games. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, drinking games reached another peak, with a wide variety of games available, encompassing topics such as worldly affairs, figures, flowers, trees, insects, birds, musical and poetic forms, dramas, novels, Chinese herbal medicine, seasonal customs, the Eight Trigrams, and dominoes. The scope of drinking games became extensive and diverse.

The earliest drinking games were primarily aimed at upholding the rules of etiquette at banquets and were a transformation, enrichment, and development of drinking customs. They served as an important means of enhancing the enjoyment and liveliness of banquets, blending culture with alcohol. In ancient times, there were even officials responsible for overseeing drinking games, known as “Li Zhi Jian” and “Zuo Zhu Shi.” These officials enforced the rules of drinking games, which aimed to restrict alcohol consumption rather than encourage excessive drinking.

Over time, as history progressed, drinking games gradually evolved into activities for entertainment and amusement during banquets. Some of the original etiquette elements were lost, and drinking games became more focused on lively interaction, competition, and even as a means of imposing penalties for drinking.

Modern Wine Etiquette

In contemporary gatherings and banquets, the phrase “ganbei” (cheers) is frequently heard. With the ganbei command, people raise their glasses, either sitting or standing, clink them together to make a sound, and then consume the entire contents. Anyone who refuses to drink faces the risk of being penalized with three additional glasses.

In fact, the tradition of ganbei is not a recent invention but has been part of ancient drinking etiquette. Its symbolism lies in the idea that whoever proposes the toast should drink first as a sign of respect and demonstrate that they have emptied their glass.

If there remains a single drop of wine in the glass, the penalty is to drink an additional glass. The person being toasted must respond in kind by offering a toast back.

At the dining table, it is common for young men to loudly exclaim, “Then I’ll drink first as a sign of respect!” followed by downing a glass in one go. This action unintentionally carries on the concept of “offering wine” from ancient wine etiquette. However, besides showing respect, the act of drinking first in ancient times had an even more significant meaning: to reassure the other person, “This wine is not poisoned, my friend, so rest assured and drink!”

Why did ancient Chinese prefer to drink warm wine?

In history, the concept of warming wine dates back to ancient times. Bronze wine vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties already included utensils for warming wine. In the Tang dynasty, poet Li Bai wrote in his work “Lidong”: “Ink freezes, and I’m too lazy to write new poems. The cold stove warms the delicious wine.” Similarly, Song dynasty poet Lu You wrote in his work “Spring Day”: “Late in the day, I taste boiled wine in the garden, accompanied by the gentle breeze in the courtyard,” both describing the scenes of boiling and warming wine.

In reality, the reason for warming wine stems from the fact that ancient brewing techniques were not very advanced, and most wines contained impurities, some of which were even harmful to the human body. By slightly heating the wine before drinking, these impurities could evaporate, reducing their impact on the body.

This concept is also described in the classic novel “Dream of the Red Chamber.” There, when Jia Baoyu was about to drink cold wine, Xue Baochai advised him, saying, “Baodi, with all the miscellaneous knowledge you learn daily, don’t you know that wine has a hot nature? It should be consumed warm so that it quickly disperses. If you drink it cold, it congeals inside, burdening your organs. Won’t that harm you? You should change this habit. Please stop drinking it cold,” highlighting the benefits of warm wine for one’s health.

Ancient Wine Utensils and Nobility

In ancient China, bronze vessels, especially those related to wine, accounted for a significant proportion in terms of variety and quantity.

For example, in the burial goods accompanying the “Fu Hao Tomb” in the Yin ruins, there were over 200 items, with wine vessels making up more than 70%, including jia, jue, gu, and he, among other types. This indicates that the aristocratic class of that time had a strong fondness for wine. During the Shang and Zhou periods, wine vessels not only had a wide variety but also displayed fine craftsmanship.

Rong Geng and Zhang Weizhi’s “A Comprehensive Discussion on Yin and Zhou Bronzes” classified the pre-Qin period wine vessels into three categories: vessels for boiling or warming wine, including jue, jia, gu, and he; vessels for containing wine, such as zun, gong, yi, you, and hu; and vessels for drinking wine, including gu and zhi.

The title “jue” used for ancient noble ranks corresponds to the hierarchy of wine vessels. The highest-ranking individuals used jue, which could hold one unit of wine; the next rank used zhou, which could hold two units of wine; the third rank used gu, which could hold three units of wine; the fourth rank used jiao, which could hold four units of wine; and the fifth rank used cups, which could hold five units of wine. The smaller the capacity of the wine vessel, the higher the status.

There was also a distinction in the containers used for serving wine. Vessels of rank three or higher used large zun, while others used large hu. Towards the end of the Spring and Autumn period, these elaborate wine ceremonies were simplified, and both common people and high-ranking officials used zhou or gu vessels.

The character “zun” is commonly used in modern Chinese to denote respect or nobility. However, in ancient times, “zun” also referred to a wine vessel, similar to a “zun.” The phrase “life is like a dream, offer a toast to the moon in a zun” mentions the “zun” as a wine vessel.

The use of “zun” began in the early Western Zhou period and generally had a round shape, while square zun had a square mouth and body. The Four Sheep Square Zun derived its prestigious name from its depiction of four sheep and four dragons facing each other, representing the supreme dignity of the wine ritual.

In the Guangdong Provincial Museum, there is a bronze he with dragon motifs from the Western Zhou period. It has an elegant shape, a solid form, intricate patterns, and fine craftsmanship, making it a treasured artifact of the museum.

So, what exactly is a he? It is a type of mixing vessel for wine, similar to the later Western-style punch bowl or cocktail shaker. Ancient people would mix wine and water in the he and then pour it into cups. The purpose was to control the concentration of the wine.

Why didn’t ancient cups have handles?

The reason lies in the concept of “etiquette.” Throughout Chinese culture, it has been considered impolite to use only one hand for tasks. In the context of wine etiquette, it was emphasized that drinking wine should be done with both hands holding the cup to signify solemnity and respect.

Additionally, ancient people paid great attention to the participants, timing, occasion, and manner of drinking. They believed that the best drinking companions should be refined, straightforward, and open-hearted confidants. The ideal drinking locations included beneath flowers, in bamboo groves, high pavilions, painted boats, secluded chambers, open fields, famous mountains, and lotus pavilions. The best times for drinking were in the clear autumn, amidst fresh greenery, after rain, amidst accumulated snow, under the new moon, or in the cool evening. Therefore, as drinking vessels, cups naturally pursued an aesthetic of elegance.

chinese drinking games

The drinking game you described is a traditional Chinese drinking custom known as “Jiu Ling.” It is a game played during a banquet or gathering to add entertainment. In this game, one person is selected as the “commander” or “master,” and the others take turns following the commander’s instructions to recite poetry, create word associations, or engage in similar activities. Those who fail to follow the instructions or lose the game are typically required to drink alcohol as a penalty. The person leading the game is also referred to as the “commander of drinks” or “commander of the banquet.”

Jiu Ling is a unique aspect of Chinese drinking culture. It has a long history, originating from the Western Zhou Dynasty and becoming more refined during the Sui and Tang Dynasties.

Origin:

Jiu Ling emerged as a drinking game during banquets and was particularly popular among the literati. They often composed poems and writings to praise the game. The poet Bai Juyi wrote, “Drinking breaks the sorrows of spring; with wine, we pluck flower branches.” During the Han Dynasty, Jia Kui wrote a book titled “Jiu Ling” about drinking games. In the Qing Dynasty, Yu Xiaopei compiled a four-volume book called “Jiu Ling Cong Chao.”

Types of Jiu Ling:

Jiu Ling can be classified into “Ya Ling” (elegant commands) and “Tong Ling” (general commands). Ya Ling involves reciting poetry, creating couplets, and other activities where participants must follow the theme and style set by the initial command. Failure to do so results in a penalty of drinking. Ya Ling requires participants to be quick-witted, creative, and knowledgeable, as it showcases their literary talents.

Tong Ling involves dice rolling, drawing lots, finger guessing games, or number guessing. Tong Ling games create a lively atmosphere at banquets but can be perceived as crude, noisy, and lacking in sophistication.

Jiu Ling is not only about drinking but also includes activities like composing poems, solving riddles, and physical games. It requires participants to be quick-witted, talented in literature, and have a flair for creativity. Thus, Jiu Ling represents both the traditional hospitality of the Chinese and the culmination of their drinking artistry and intellectual abilities.

During the Wei and Jin Dynasties, literati and scholars enjoyed imitating ancient customs, engaging in leisurely activities, and indulging in the arts while drinking. These elegant forms of Jiu Ling, reminiscent of the pure and tranquil scenery of spring, went beyond simple penalties and included activities such as reciting poems. One popular variation involved sitting by a gently flowing stream, where literati and scholars composed poetry after drinking wine poured into a cup that floated downstream. The most famous example of this is the Lanting Gathering of the Nine Worthies in the ninth year of Emperor Mu of Jin’s Yonghe era (353 AD). It featured calligrapher Wang Xizhi and 41 other famous literati gathering in Lanxi, where they expressed their emotions and wrote numerous poems. Wang Xizhi’s famous calligraphy masterpiece, “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering,” was created during this event. However, in the folk traditions, Jiu Ling could be simplified to just drinking without the requirement of composing poetry.

Jiu Ling is a unique way for the Han Chinese to add liveliness and entertainment to their drinking gatherings. With its long history, Jiu Ling has evolved into various forms and styles. It originated as a means to maintain order at banquets and gradually transformed into a game of penalties. In ancient times, activities like archery contests, such as “yan she,” or “tou hu,” which involved throwing arrows into a pot, were popular methods of deciding winners and losers, with the losers being required to drink alcohol. Jiu Ling can be seen as a catalyst that enlivens the atmosphere of a banquet, especially when guests may not know each other well.

There are various ways to play Jiu Ling, ranging from simple to complex. The methods used by literati and scholars differ significantly from those used by ordinary people. Literati often engage in activities like reciting poetry, creating couplets, solving riddles, and more. Ordinary people commonly use simpler methods that require no preparation, such as the “same number” game, which is similar to rock-paper-scissors. Another popular game is “Pass the Flower with Drumming,” which involves passing a bouquet of flowers while a drum is beaten. When the drum stops, whoever is holding the bouquet must drink. If the bouquet lands between two people, they may use games like rock-paper-scissors to determine the loser. “Pass the Flower with Drumming” is suitable for people of all ages and is commonly played by women. This scene is vividly depicted in the novel “Dream of the Red Chamber.”

In conclusion, Jiu Ling is a unique drinking culture specific to the Han Chinese. Its various forms and styles have been passed down through generations.

how much alcohol in ancient Chinese wine?