Calligraphy goes beyond good handwriting. It is a form of art and expression of self, culture, or religion. This art is valued by many religions and cultures, especially in Chinese culture. Chinese calligraphy is the most significant form of visual arts that sets the standard for all other Chinese paintings in China. The high status of calligraphy reflects the importance of the word to Chinese people, with an entire culture devoted to the word.

To better understand Chinese culture and the role it plays in Chinese culture, we will be looking at when it was invented, who invented it, and why. We will also cover why Chinese calligraphy is so important and some of the famous Chinese calligraphy artists.

what is Chinese calligraphy?

Chinese calligraphy, or “Shufa” in Chinese, is a unique traditional art form in China. Chinese characters were created by the laboring people and initially recorded through pictographs. After thousands of years of development, they evolved into the current writing system. With the invention of brush writing by our ancestors, calligraphy emerged. Throughout history, calligraphy has primarily been practiced using a brush to write Chinese characters. Other writing forms, such as hard-pen and finger writing, share fundamental similarities with brush calligraphy rather than being entirely different.

Narrowly speaking, calligraphy refers to the method and principles of writing Chinese characters with a brush. It includes aspects such as holding the brush, stroke execution, dotting, structuring, and layout (distribution, line order, composition). For example, holding the brush involves grasping it firmly with the hand and applying even pressure with all five fingers. Stroke execution requires precise control of the brush tip and ink saturation. Dots and strokes should convey the intended meaning, with a balance between smoothness and sharpness. The structure of characters emphasizes their form and mutual coherence. Distribution of characters should be intricate yet harmonious, with appropriate spacing and the interplay of solid and empty spaces. Inscriptions can vary between ancient and contemporary styles, with different sizes and heights.

Broadly speaking, calligraphy refers to the rules of writing language symbols. In other words, calligraphy involves using the brushwork, structure, and composition of characters based on their linguistic characteristics and meanings to create artistic pieces. With the development of cultural endeavors, calligraphy has expanded beyond the use of a brush and writing Chinese characters, encompassing a broader range of possibilities. For example, tools used for calligraphy have diversified, including brushes, pens, computer devices, spray guns, and everyday tools. Pigments go beyond traditional black ink, incorporating various colors, binding agents, chemicals, and enamel paints. The “Four Treasures of the Study” – brush, ink, paper, and inkstone – have also expanded in meaning, with numerous variations. In terms of brush-holding techniques, people may use their hands, feet, or other body parts, and there are even methods that don’t involve a brush, such as finger writing or squeezing techniques. Calligraphy is not limited to the Chinese language alone; minority languages and scripts have also gained recognition in the realm of calligraphy, such as the Mongolian script. In terms of style and composition, besides the authentic traditional schools, a modern school known as the “Intentional” school has emerged, which combines traditional calligraphy with innovative elements, emphasizing variation and integrating poetry, calligraphy, and painting into a unified form. In Japan, some calligraphers have discarded the linguistic aspect of characters, emphasizing their “imagery” instead, resulting in the “Mokusho” school, which creates various visual representations of characters using different brushwork intensities, speeds, and variations in brush placement. Although this school highlights the “imagery” aspect, it faces limitations as not all Chinese characters are pictographic. This highlights the ongoing challenges and developments in calligraphy. Like other art forms, calligraphy is continuously evolving and changing, and this requires significant attention from calligraphy practitioners.

what is Chinese calligraphy called?

Chinese calligraphy has various aliases, such as “zihua” (literally “word and painting”), “mobao” (literally “ink treasure”), “zhuanke” (literally “seal engraving”), and “linchi” (literally “approaching the pond”).

Calligraphy, also known as “zhuanke,” is an essential part of traditional Chinese culture and is hailed as the “essence of brush and ink.”

The honorable term for calligraphy, “linchi,” is associated with Wang Xizhi, a calligrapher from the Eastern Jin Dynasty. Wang Xizhi dedicated himself to practicing calligraphy and would wash his brushes and inkstones in the pond in front of his house after writing every day. Over time, the water in the pond turned deep black. As a result, people use the term “linchi” to represent diligent study and practice of calligraphy.

Chinese calligraphy encompasses the artistic writing of all Chinese characters, and different styles of Chinese characters have their own aliases, as follows:

Shiguwen: Also known as Liejie or Yongyi Stone Inscriptions, it is the earliest surviving engraved stone text in China.

Jiaguwen: Jiaguwen is a cultural product of the Shang Dynasty (approximately 17th century BCE to 11th century BCE) and has a history of more than 3,600 years. It is often referred to as the Yin Xu script as many of the inscriptions were found at the Yin Ruins. Due to the prevalence of oracle inscriptions, it is also known as the “Divination Inscriptions.”

Qiwen: An alias for Jiaguwen. Qi means “to carve,” and it refers to the use of a carving knife to inscribe characters on tortoise shells or animal bones.

Ke Fu: A special-purpose seal script used during the Qin Dynasty.

Dazhuan: Dazhuan was widely used during the Western Zhou Dynasty and is said to be created by Yi. Depending on the medium, Dazhuan has aliases such as Jinwen (or “Zhongdingwen”) and Zhouwen.

Jinwen: Jinwen, slightly later than Jiaguwen, refers to inscriptions cast or engraved on bronze objects. Zhouwen was used by the ancient state of Qin and served as the precursor to Xiaozhuan. The name “Zhouwen” comes from the collection of 223 characters found in the “Shizhoupian” written during the Spring and Autumn period.

Niaochongshu: Also known as “Chongniaozhuan” or “Chongshu.” It refers to the flower-like style in seal script. This font existed during the Spring and Autumn period and was often cast or engraved on weapons and bells. The strokes are often composed of simplified animal shapes, resembling a combination of calligraphy and painting, and are quite interesting. This style is commonly used in flags, tokens, and can also be found in Han dynasty seals.

Shushu: Also known as “Bangshu.” It now refers to writing characters that are larger than one square foot per character.

Yujinzhuan: Also known as “Yuzhuzhuan.” It is a type of seal script characterized by smooth and rounded brushstrokes, resembling the appearance of jade veins.

Tiexianzhuan: A type of Xiaozhuan, which emerged from the “Taishan Engravings” and “Langyatai Engravings” of the Qin Dynasty. It features agile, fine, iron-like brushstrokes, with a stroke quality resembling a straight line, hence the name. In later years, it was referred to as “Qianxianzhuan” during the Tang Dynasty due to the calligraphy of Li Yangbing.

Lishu: Also known as “Zuoshu” or “Lishu.” It is a style of writing with flat and angular forms, making it easy to write. It originated in the Qin Dynasty and became widespread during the Han and Wei dynasties.

Caotuan: Another name for Feibai. It refers to seal characters written in the cursive script style.

Kedouwen: Also known as “Kedoushu” or “Kedouzhuan.” It is a colloquial term for handwritten seal script (including ancient and Zhuwen). It is named so because the brush is dipped in ink or lacquer for writing. The strokes start thick and end thin, resembling tadpoles.

Miaozhuan: Also known as “Moyinzhuan.” It is a type of seal script used for making imitations of seals during the Han Dynasty. It is one of the “Six Scripts of Wang Mang.”

Kaishu: Also known as “Zhengkai.” The standard for Kaishu is its squareness and neatness, distinguishing it from the long and vertical Xiaozhuan and the horizontal Lishu. It has a hook shape without wave-like strokes. Turnings of strokes are replaced by straight angles. Additionally, the writing order in Xingshu is not fixed in the oracle bones and bells, allowing for both left-to-right and right-to-left writing. However, after the Qin Dynasty, the writing direction was uniformly right-to-left without exception.

Caoshu: Also known as “Gaoshu.” In the broad sense, it refers to any handwriting that is scribbled or messy. In a narrow sense, it specifically refers to a cursive script characterized by continuous, flowing strokes. During the mid-Tang Dynasty, Zhang Xu and Huaisu wrote in a more unrestrained and eccentric style called “Kuangcao,” distinguishing it from “Jincao” or “Jincao.” Kuangcao is also known as “Dacao” and represents the most uninhibited form of cursive script.

Xingshu: Also known as “Xingyashu.” Xingshu is generally based on the form of Kaishu but emphasizes smooth and expedient writing. It is neither as illegible as Cao Shu nor as refined as Kaishu. It is a widely used handwritten script in society. The strokes flow continuously, with no significant breaks, resembling flowing water and clouds, creating a sense of eternal vitality.

Common styles of Chinese calligraphy

Yan (颜) Style: Yan is a style created by the Tang dynasty calligrapher Yan Zhenqing. It is known for its new and majestic appearance, strict rules, and grandeur. Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy is characterized by its elegance, masculine beauty, and artificial beauty, making it a prime example of the fusion of calligraphic beauty and personal character. Yan Zhenqing’s script is often referred to as “Yan style” or “Yanliu” (combining Yan and Liu Gongquan) and is highly regarded.

Liu (柳) Style: Liu refers to the calligraphy works of Liu Gongquan, one of the four great calligraphers of the Tang dynasty. Liu Gongquan’s calligraphy is known for its graceful and powerful strokes. His script is often referred to as “Liu style” or “Liushaoshi” (combining Liu and Shao Shi, his official title).

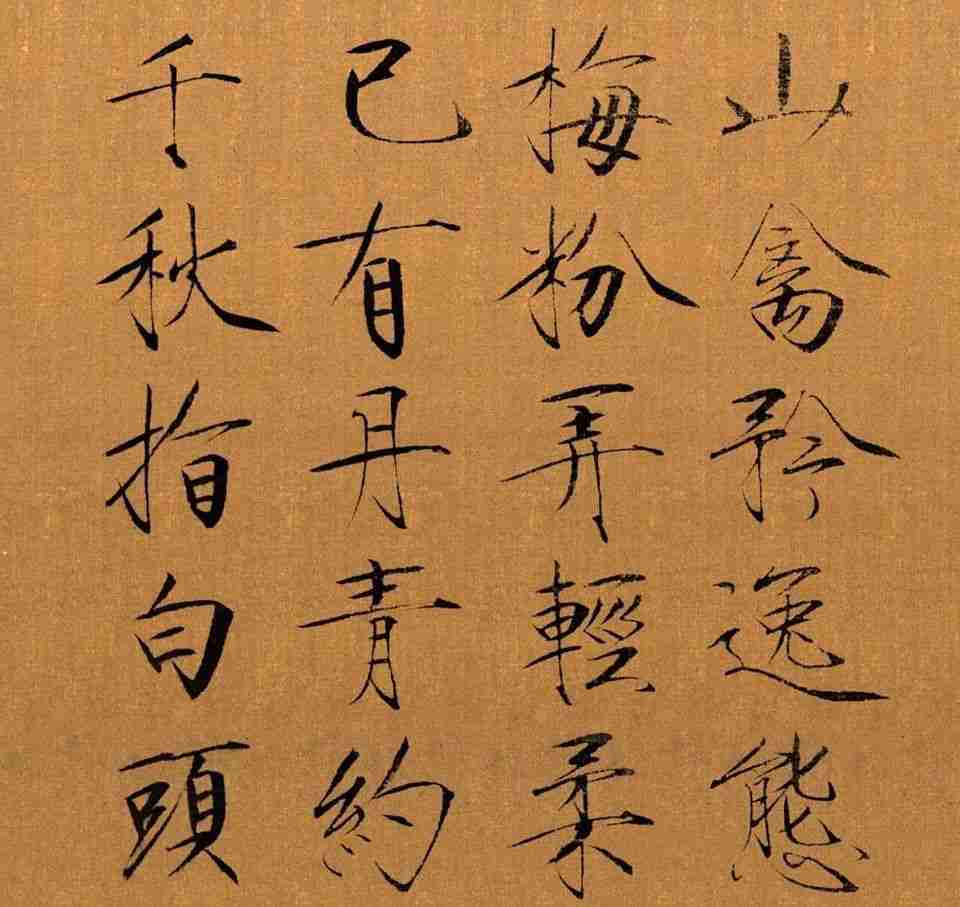

Zhao (赵) Style: Zhao style refers to the calligraphy of Zhao Mengfu, a famous painter in the Yuan dynasty and one of the four great calligraphers of the regular script (kai) and semi-cursive script (xingshu) styles. Zhao Mengfu’s style features flattened and square-shaped characters with rounded and elegant strokes. His calligraphy shows a balance between regular and semi-cursive script, giving it a flowing and dynamic appearance.

Ou (欧) Style: Ou style is associated with Ouyang Xun, a calligrapher from the late Southern Dynasties and early Tang dynasty. Ouyang Xun is considered one of the greatest calligraphers of regular script (kai) and semi-cursive script (xingshu). His script is known as “Ou style” and is mentioned alongside Yan, Liu, and Zhao styles as the four great calligraphic styles of the Tang dynasty.

Shou Jin (瘦金) Style: Shou Jin style is a unique calligraphic style created by Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty. It is characterized by its distinctive and individualistic appearance, differing significantly from traditional Jin and Tang dynasty styles. Shou Jin style is known for its slim and delicate strokes and is represented by works such as the “Thousand-Character Classic” and the “Fang Shi” poem.

what is Chinese calligraphy used for?

Chinese calligraphy serves various purposes and holds significant cultural and artistic value in Chinese society. Here are some common uses and functions of Chinese calligraphy:

Artistic Expression: Chinese calligraphy is considered a form of visual art. Calligraphers use brush and ink to create aesthetically pleasing and expressive characters, focusing on elements like brushstrokes, composition, and rhythm. Calligraphy artworks are highly valued for their artistic beauty and are displayed and appreciated in galleries, exhibitions, and private collections.

Cultural Heritage: Chinese calligraphy is deeply rooted in Chinese history and culture. It serves as a means to preserve and pass down the rich traditions of Chinese writing. Through calligraphy, the historical development of Chinese characters and writing styles is documented and celebrated.

Spiritual and Philosophical Practice: Calligraphy is often seen as a meditative and introspective practice. It requires concentration, discipline, and a deep understanding of the characters being written. Many practitioners engage in calligraphy as a means of cultivating inner harmony, self-reflection, and spiritual growth.

Education and Academic Study: Chinese calligraphy has long been an integral part of Chinese education. Students learn calligraphy to develop their writing skills, discipline, and appreciation for Chinese culture. Calligraphy is also studied academically as a subject in art schools and universities, focusing on its history, styles, and techniques.

Personal and Formal Correspondence: Calligraphy has been traditionally used for personal and formal correspondence, including writing letters, poems, invitations, and inscriptions. Beautifully written calligraphy adds an extra level of elegance and thoughtfulness to written communication.

Seals and Signatures: In Chinese culture, seals hold significant importance. Calligraphy is used to create personalized seals, known as “yinzhang” or “chop.” These seals are used as signatures and authentication marks on official documents, artworks, and personal belongings.

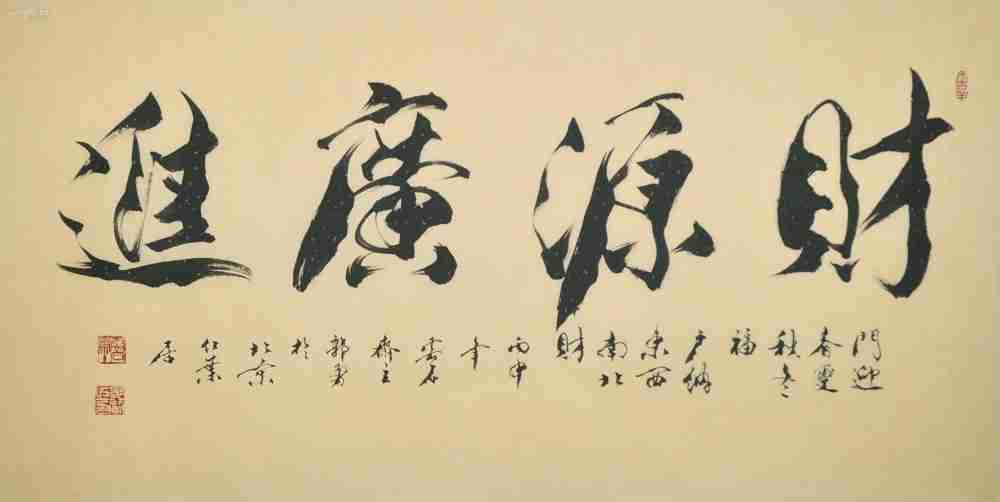

Decorative and Functional Applications: Calligraphy is often employed in decorative and functional items, such as scrolls, wall hangings, screens, ceramics, and textiles. These items are adorned with calligraphic inscriptions, conveying blessings, philosophical quotes, or auspicious wishes.

Art Appreciation: Calligraphy artworks possess unique artistic charm. Through appreciating calligraphy works, one can experience and comprehend the emotions, artistic conception, and artistic style expressed by the artist. It has a profound influence on people’s aesthetics and emotions.

Home Decoration: Calligraphy artworks can be used as home decorations, adding cultural atmosphere and artistic ambiance to the house, making it more vibrant, interesting, and tasteful.

Gift Giving: Calligraphy artworks are distinctive gifts that can be given to family and friends on occasions such as birthdays, weddings, and holidays, conveying sentiments and emotions. They can also be given as corporate gifts to clients, showcasing corporate culture and brand image.

Investment and Collecting: Some calligraphy artworks with historical and cultural value, recognized and appraised by the market, can be treated as investment items and collectibles, with certain preservation and appreciation potential.

Overall, Chinese calligraphy serves as a means of artistic expression, cultural preservation, spiritual practice, education, and communication. It is highly esteemed for its aesthetic beauty, historical significance, and connection to Chinese traditions.

types of Chinese calligraphy

篆书 (Zhuan Shu):

Zhuan Shu refers to both Da Zhuan (Great Seal Script) and Xiao Zhuan (Small Seal Script). Oracle Bone Inscriptions, dating back over 3,000 years, are the earliest known recognizable characters and were primarily used for divination purposes. The strokes are thin, upright, and contain more straight lines. The brush can be square, round, or pointed, with a prevalence of hanging strokes resembling a suspended needle. Da Zhuan refers to Jin Wen (Bronze Inscriptions), Zhou Wen (Zhou Dynasty Scripts), and the scripts of the six kingdoms, preserving the evident characteristics of ancient pictographic characters. Xiao Zhuan, also known as “Qin Zhuan,” was the standardized script of the Qin State and a simplified form of Da Zhuan. Its features include even and uniform forms, easier to write compared to Zhou Wen.

Lishu (隶书):

Lishu, also known as Han Lishu, is a commonly seen formal script in Chinese characters. Its writing style is slightly wider and flatter, with long horizontal strokes and short vertical strokes, forming a rectangular shape. It emphasizes “silkworm head and goose tail” and “one wave, three bends.” Lishu originated during the Qin Dynasty, compiled by Cheng Miao, and reached its peak during the Eastern Han Dynasty. It has had a significant influence on calligraphy throughout history, leading to the saying “Han Lishu, Tang Kai.” Examples include the “Han Lu Xiang Han Le Manufacturing Confucius Temple Ritual Vessel Inscription,” also known as the “Han Mingfu Confucius Temple Inscription,” the “Han Le Inscription,” and others. Created in the second year of Yongshou in the Han Dynasty (156 CE), it is a Lishu inscription measuring 227.2 cm in height and 102.4 cm in width. It is kept in the Confucius Temple in Qufu, Shandong Province. Inscribed on all four sides, the inscription contains 16 rows with 36 characters in each row, with the names of nine individuals inscribed at the end.

Kaishu (楷书):

Kaishu, also known as Zheng Kai, Zhen Shu, or Zheng Shu, gradually evolved from Lishu, simplified further, and became more balanced and regular with horizontal and vertical strokes. Kaishu implies a standard form and was mentioned by Zhang Huaiyi in “Shu Duan.” People of the Six Dynasties still habitually used it. For example, Yang Xin’s “Cai” text and Wang Sengqian’s “Lun Shu: Wei Dan Biography” states, “Dan’s character Zhongjiang, a person from Jingzhao, is skilled in Kaishu.” This is a brief reference to “Ba Fen Kaifa” (eight-part Kaishu). It was only during the Northern Song Dynasty that it replaced the term “Zheng Shu.” The content clearly differs from the ancient name, with name and reality being different or reality being the same with a different name.

Xingshu (行书):

Xingshu developed from Lishu and falls between Kaishu and Caoshu. It is a type of script that serves as a compromise between the slow writing speed of Kaishu and the difficulty of recognition in Caoshu. “Xing” means “to walk,” hence it is not as messy as Caoshu nor as formal as Kaishu. Essentially, it is the cursive form of Kaishu or the regularized form of Caoshu. When Kaishu dominates over Caoshu, it is called “Xing Kaishu,” and when Caoshu dominates over Kaishu, it is called “Xing Caoshu.”

Caoshu (草书):

Caoshu is a style of Chinese calligraphy characterized by its simplified structure and continuous strokes. It originated during the Han Dynasty as a simplified form of writing for convenience based on Lishu. It can be further divided into Zhang Cao, Jin Cao, and Kuang Cao, with the latter being the most unrestrained and wild. The “Shuowen Jiezi” states, “Cao Shu appeared during the Han Dynasty.” Caoshu began during the early Han Dynasty, characterized by summarized characters, departing from the rules of Lishu, with a focus on freedom and swiftness. Due to its resemblance to grass, it is called Caoshu.

Why Is Chinese Calligraphy Important?

Chinese calligraphy has always been more than a form or tool of communication. It carries elements of artistry where the different Chinese characters are seen as a visual art form. It is considered a significant channel used to appreciate traditions, culture, and arts education.

The Chinese consider their calligraphy with pleasure and pride as it embodies important aspects of China’s artistic and intellectual heritage. It is also important because it was the art form of China’s educated elite. That is because to be able to pass their exams intellectuals had to learn calligraphy to pass on information. It was seen as proof that they were good people. Chinese calligraphy is therefore seen as the representation of intellects and wisdom. Another reason why Chinese calligraphy is held in high esteem is that it was a written form that unified all the languages spoken in China. Chinese also believed that Chinese calligraphy was a medium of self-expression and revelation. This was based on the intrinsic way the art was mastered.

Based on Chinese calligraphy, a lot of developments were achieved, including inkstones, paperweights, and seal carvings, in China.

What Is Special About Chinese Calligraphy?

Chinese calligraphy is known as Shufa in Chinese. Over time its practice has spread far and wide across Asia. Japanese and South Korean calligraphy is heavily influenced by Chinese calligraphy. It is because the Chinese form of calligraphy has many notable benefits, which is what makes it so special. The following are some of the major benefits you get from practicing Chinese calligraphy:

Allows you to practice hand and eye coordination

Chinese calligraphy is a strict art form that requires precise brush strokes. The aesthetical finish of your work will depend on the symmetry of each character in relation to itself and other characters. That means that the thickness of each stroke should be proportionate and in line with the character’s structure. For that, you would need an excellent mastery of the brush by training your eyes and hand movement. That is why even the best calligraphy masters spend thousands of hours practicing.

It’s therapeutic, incorporating breathe work.

For thousands of years, the practice of Shufa has been considered therapeutic. To be able to position the brush, one needs to practice breathing control. It’s believed that to produce fine work, your heart needs to be still, hence the necessity of breathing. As a result, the entire practice of Chinese calligraphy is seen as a meditative practice that is good for your overall wellbeing.

Allows your mind to be at its highest performing level

According to Psychologists, the brain is at its peak performance when it’s in a state of flow. Practicing Chinese calligraphy involves rhythmic brush writing that requires you to be fully immersed in the practice. As you get lost in that practice you improve your mind’s performance level.

When Was Chinese Calligraphy Invented?

The earliest known form of Chinese calligraphy dates back to the Shang dynasty. The first form was known as Jiaguwen. They were Chinese inscriptions done on oracle bones, that is animal bones or turtle shells. This later evolved into inscriptions done on bronze vessels, art is known as jinwen, which translates to the metal script. These vessels were normally used to offer wine and food to the ancestors.

Around the reign of the Qin dynasty when China came together, the bronze script was unified, which led to the third stage of Chinese calligraphy development. The new style was called xiaozhuan which translates to a small seal. This type of script was characterized by evenly thick lines, circles, and curves. It was established to meet the demand for record-keeping, but unfortunately, it couldn’t be written fast enough. This led to the fourth stage of development, which gave rise to the official style called lishu. This type of style was characterized by squares and short straight lines that were mainly vertical or horizontal.

Lishu was an easier style which allowed more freedom with the hand. As such, it encouraged individual artistic expression, which led to the fifth stage of development. This was the final style of Chinese calligraphy which was called zheshu, or regular style. The regular script was and is seen as the proper script type for Chinese writing. Its been in use since the Tang dynasty and has been used in everything from Chinese government documents to printed books.

Chinese calligraphy originated in the late Spring and Autumn period. During this time, the artistic transformation of traditional characters began to emerge. In pursuit of visual beauty, existing brushstrokes were adorned with dots, curves, or bird-like decorations, laying the foundation for later developments known as “bird seal script,” “insect seal script,” or “mysterious seal script.” In the Warring States period, in addition to the widespread use of cursive seal script, even inscriptions on important ritual vessels underwent a transformation from the previous neat and rigid style to a more embellished form.

Why Was Chinese Calligraphy Invented?

Today, Chinese calligraphy is an ancient and reputed artistic form in oriental world history. Initially, it was invented due to the demand for record-keeping. People wanted to record ideas and information, to preserve them for the coming generations. It came about when people realized that the language could be conveyed through pictographs which later developed to the Chinese characters today. It is now seen not just as a tool of passing on information and decorative art, but also as a great form of visual art, that has influenced calligraphy in many other countries.

Chinese calligraphy was not invented in the conventional sense. Instead, it evolved organically as a form of artistic expression and a means of communication in ancient China. The origins of Chinese calligraphy can be traced back to the ancient practice of inscribing characters on oracle bones, bronze vessels, and other artifacts. Initially, these inscriptions served as records, religious texts, and expressions of power.

Over time, calligraphy began to transcend its utilitarian purpose and develop into an art form. It became a means for scholars, intellectuals, and artists to express their thoughts, emotions, and aesthetics through the brush and ink. Calligraphy became intimately intertwined with other artistic practices, such as painting, poetry, and seal carving.

One of the key reasons for the significance and development of calligraphy in Chinese culture is the importance placed on the written word. Writing has always been highly regarded in Chinese society, and calligraphy was seen as the pinnacle of the written art. It was not merely a means of conveying information but a visual representation of one’s character, morality, and cultural refinement.

In Confucian philosophy, calligraphy was considered a fundamental component of self-cultivation and the pursuit of virtue. The act of practicing calligraphy was seen as a means of cultivating one’s character, discipline, and focus. By studying and emulating the masterpieces of renowned calligraphers from the past, individuals sought to connect with the wisdom and spirit of their ancestors.

Furthermore, calligraphy played a significant role in the transmission of culture and knowledge. The elegance and beauty of well-executed calligraphy enhanced the impact and memorability of written texts. Important documents, poetry, historical records, and religious scriptures were often meticulously transcribed and preserved through calligraphy, ensuring their longevity and cultural significance.

In summary, Chinese calligraphy emerged as a result of the deep reverence for the written word, the desire for self-expression, the pursuit of artistic beauty, and the cultural and philosophical values associated with writing in Chinese society. It evolved from a practical means of communication to a sophisticated art form that continues to be highly valued and celebrated today.

Who Invented Chinese Calligraphy?

It is not clear or proven as to who exactly invented or started Chinese calligraphy. But over its evolution, there have been a few notable figures who played an important role in making Shufa what it is today.

Shihuangdi, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty, for example, is said to have been the one who brought about the small seal style of writing. In an attempt to unify China, he instructed his prime minister to come up with a unified style of writing.

Cheng Miao is, however, noted to have evolved the small seal style into lishu, the official style. He did this over 10 years when he was in prison for offending the emperor Shihuangdi. This style of writing is what opened up a seemingly endless possibility for other calligraphers later on. No one is credited for coming up with what is called the regular style of Chinese writing, zhenshu. Wang Xizhi and his son Xianzhi are however considered to be the greatest exponents of Chinese calligraphy since then.

Who created Chinese calligraphy?

Li Si (approximately 284 BC – 208 BC), with the courtesy name Tonggu, was born in Shangcai, Chu State (present-day Shangcai County, Henan Province) during the late Warring States period.

Li Si was a prominent politician, writer, and calligrapher of the Qin Dynasty. He assisted Emperor Qin Shihuang in unifying the country and advocated for the implementation of the prefecture-county system and the abolition of the feudal system. As a key figure in the standardization of writing, Li Si made significant contributions to the development of Chinese characters.

To promote a unified script, Li Si personally created the “Cangjie Pian” in small seal script, which served as the standard model for people to copy. Additionally, Li Si adopted the new script style known as “li” (clerical script), originally created by Cheng Miao, as the official formal script.

Since then, the “variant characters” created by various vassal states since the Shang Dynasty’s oracle bone script gradually faded away. The “character creation era” of Chinese calligraphy came to an end, and it entered the “formative” era.

Emperor Qin Shihuang undertook five tours of the country’s prefectures and counties, and each time he entrusted Li Si with the task of inscribing stone tablets to record his achievements. The representative works among them include the “Taishan Stone Inscription,” “Liangya Stone Inscription,” “Yishan Stone Inscription,” and “Kuji Stone Inscription,” collectively known as the “Four Mountain Stone Inscriptions of Qin.” These stone inscriptions are representative of the epigraphic style.

Furthermore, it is said that after Emperor Qin Shihuang unified the country, he had a jade seal called the “He Shi Bi” carved. On the front side, it was engraved with the eight characters “Received the Mandate from Heaven, Longevity and Prosperity.” Li Si was also responsible for carving these characters in small seal script.

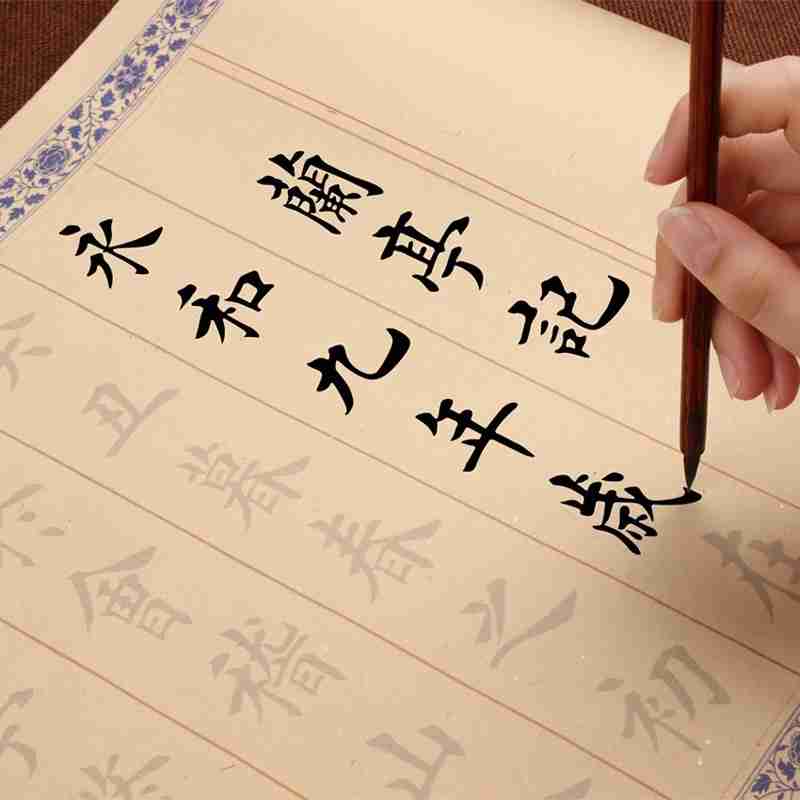

what do you need for Chinese calligraphy?

To practice Chinese calligraphy, you will need several essential tools and materials. Here are the key items:

Brush: The brush is the primary tool used in Chinese calligraphy. It is typically made from animal hair, such as goat, wolf, or weasel, attached to a bamboo or wooden handle. The brush’s quality and stiffness can vary, affecting the stroke thickness and control.

Ink: Ink is a vital component in Chinese calligraphy. Traditional ink comes in solid form, usually in ink sticks, which are ground on an inkstone with water to create liquid ink. Alternatively, liquid ink can be used, commonly available in bottled form.

Inkstone: An inkstone is a flat stone surface used for grinding ink sticks with water to create ink. It provides a smooth and controlled environment for ink preparation.

Rice Paper: Rice paper, also known as Xuan paper, is a thin and absorbent paper used for Chinese calligraphy. It is typically made from rice straw, bamboo, or other plant fibers. The smooth texture of rice paper allows ink to spread and dry evenly.

Paperweight: A paperweight is used to hold the rice paper in place while writing to prevent it from moving or wrinkling. It can be made of various materials, such as stone, metal, or wood.

Water: Water is required for diluting ink and cleaning brushes and inkstones.

Brush Rest: A brush rest is a small stand or holder used to hold the brush horizontally when not in use. It prevents the brush’s bristles from being damaged or deformed.

Seal: While not essential for calligraphy practice, a seal is often used to sign and mark completed calligraphy artworks. A seal is typically made of stone or other materials, with engraved characters or designs.

These are the basic tools and materials needed for Chinese calligraphy. Additionally, a practice mat or cloth, ink pad, and brush hanger may be useful for organizing and protecting your calligraphy supplies.

what is Chinese calligraphy ink made of?

Ink is the most important tool in brush calligraphy, primarily made from carbon soot, adhesive materials, additives, and solvents. It is typically manufactured through mechanical processes. Additives include stabilizers, penetrants, wetting agents, preservatives, fragrances, etc. Alcohol and bleach powder are required for preparation. The ink is first dissolved in alcohol and then treated with bleach powder.

what is Chinese calligraphy paper made of?

There are various types of paper used for writing and painting with a brush, including Yuan Shu paper, Xuan paper, Mao Bian paper, etc. Yuan Shu paper is made from plant fibers such as bamboo, bark, old cloth, hemp, and straw. The process involves soaking, cooking, natural bleaching, and grinding the fibers into pulp. The pulp is then manually scooped onto a bamboo screen and pressed dry before being dried on a heated wall. The resulting paper is pure white (or slightly yellow), uniformly soft, and easily absorbs ink, remaining durable and unchanged over time.

what are Chinese calligraphy brushes made of?

The bristles of a brush are made from materials such as goat hair, rabbit hair, yellow weasel, rat whiskers, rat tail, tiger hair, horse hair, deer hair, etc.

Brushes are classified based on the materials used to make the brush head, including goat hair brush, wolf hair brush, purple hair brush, combination hair brush, etc.

Goat Hair Brushes: The brush head is made from goat hair. Goat hair brushes are relatively soft, have a high ink absorption capacity, and are suitable for creating round and solid strokes. They are also durable compared to wolf hair brushes. Common types of goat hair brushes include Da Kai brushes, Jing Ti brushes, Lian Feng brushes, Ping Feng brushes, Ding Feng brushes, Gai Feng brushes, Tiao Fu brushes, Yu Sun brushes, Yu Lan Rui brushes, and Jing Zhi brushes.

Wolf Hair Brushes: The brush head is made from the hair on the tail of a yellow weasel. Wolf hair brushes have a stiffer bristle, suitable for calligraphy and painting, but they are less durable than goat hair brushes and are usually more expensive. Common varieties include Lan Zhu brushes, Xie Yi brushes, landscape and flower brushes, leaf vein brushes, clothing texture brushes, Hong Dou brushes, small precision brushes, deer and wolf hair brushes for calligraphy and painting, leopard wolf hair brushes, special longfeng wolf hair brushes, and superior longfeng wolf hair brushes.

Purple Hair Brushes: The brush head is made from rabbit hair, known for its glossy purple-black color. This type of brush has a sharp and pointed tip, with even stronger elasticity than wolf hair brushes.

Combination Hair Brushes: The brush head is made from two different types of animal hair with different softness. Common varieties include goat and wolf combination brushes, goat and purple combination brushes, such as 55% goat hair and 45% wolf hair, or 70% purple hair and 30% goat hair. These brushes combine the advantages of both goat hair and wolf hair brushes, with a balanced level of firmness and flexibility. They are commonly used by calligraphers and painters. Varieties include blending type and heart-covering type.

what does Chinese calligraphy look like?

Chinese calligraphy is characterized by its unique and distinctive visual appearance. Here are some key features of Chinese calligraphy:

Brushstrokes: Chinese calligraphy emphasizes the expressive power of brushstrokes. Various types of strokes are used, including thick, thin, straight, curved, and tapered strokes. The brush is held at different angles to create different effects.

Balance and Harmony: Chinese calligraphy values balance and harmony in its composition. The characters or words are carefully arranged on the paper, creating a sense of equilibrium and rhythm. The spacing between strokes and characters is considered important for achieving visual balance.

Line Variation: Chinese calligraphy exhibits a wide range of line variations. It includes bold and powerful strokes as well as delicate and graceful lines. The pressure applied to the brush determines the thickness and intensity of the strokes.

Structure and Proportions: Chinese calligraphy pays attention to the structure and proportions of characters. Each character is composed of different strokes that need to be executed with precision and accuracy. Proper proportions between strokes and components are crucial to achieve a harmonious overall appearance.

Empty and Full Spaces: Chinese calligraphy utilizes the concept of empty and full spaces, known as positive and negative spaces. The balance between the inked areas and the blank spaces is carefully considered to create a visually pleasing composition.

Artistic Expression: Chinese calligraphy is not only about writing characters accurately but also about conveying emotions and artistic expression. Calligraphers often infuse their work with their personal style, creativity, and individual interpretation.

Overall, Chinese calligraphy showcases a combination of technical skills, artistic expression, and cultural aesthetics, resulting in visually captivating and meaningful compositions.

why is calligraphy important to Chinese culture?

Calligraphy is an important component of traditional Chinese culture. It is not only an art form but also a means of cultural inheritance and expression. As an art form, calligraphy possesses unique aesthetic value and artistic charm, with its beauty derived from the perfect combination of form and artistic conception. However, the significance of calligraphy lies even more in its inheritance and expression of Chinese culture.

Chinese calligraphy has a long history, dating back to ancient oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions. In Chinese culture, calligraphy has always been regarded as an elegant art form. It serves not only as a means of written expression but also as a way to understand the history and development of Chinese culture, as well as its essence and connotations.

As a means of cultural inheritance, calligraphy not only preserves the evolution and development of Chinese characters but also carries the essence and connotations of Chinese culture. In Chinese culture, calligraphy is seen as a way to cultivate one’s moral character. Through the practice of calligraphy, individuals can enhance their self-cultivation, refine their taste, and develop their sense of beauty and aesthetic appreciation. Additionally, calligraphy serves as a mode of expression for traditional culture. Through calligraphy works, the essence and connotations of Chinese culture can be conveyed, along with its values and thoughts.

The significance of calligraphy to Chinese culture also lies in its inheritance and development. In Chinese culture, calligraphy has always been considered a representative of traditional culture, and its inheritance and development hold great importance for the development of Chinese culture. In modern society, calligraphy, as a representative of traditional culture, still holds a significant position and role. Through the inheritance and development of calligraphy, more people can come to understand the essence and connotations of Chinese culture, and experience the charm and vitality it possesses.

Calligraphy, as an integral part of traditional Chinese culture, holds great significance and plays a crucial role. It is not only an art form but also a means of cultural inheritance and expression. Through calligraphy, we can gain insights into the history and development of Chinese culture, as well as its essence and connotations. The inheritance and development of calligraphy have profound implications for the overall development of Chinese culture. Therefore, it is essential to value the inheritance and development of calligraphy, enabling more people to appreciate the charm and power of Chinese culture.

Origin of Chinese Calligraphy

The art of Chinese calligraphy began during the emergence of Chinese characters. “Sound cannot be transmitted to distant places or preserved for future times, so writing was created. Writing is a means to capture the traces of meaning and sound.” (From “Shu Lin Zao Jian” by Ma Zonghuo). Thus, writing was born. The earliest works of calligraphic art were not written characters but rather symbolic engravings—pictographic or ideographic symbols.

The depiction of Chinese characters first appeared on pottery. The initial symbolic engravings only represented vague and abstract concepts without precise meanings. Over 8,000 years ago, during the Majiayao and Peiligang cultures in the Yellow River basin, there were numerous pictographic symbols found on handmade ceramics. These symbols were a blend of primitive communication, recording, and decorative functions. Although these symbols were not recognizable Chinese characters to modern individuals, they were the rudiments of Chinese characters.

Around 6,000 years ago, at the Banpo site of the Yangshao culture, simple pictographic engravings on colored pottery were discovered. These symbols differentiated themselves from decorative patterns, advancing the development of Chinese characters further. This can be regarded as the origin of Chinese writing.

Subsequently, during the Erlitou and Erligang cultures, pottery fragments with carved symbols were found. There were twenty-four different symbols, some resembling the oracle bone script of the Yin ruins, each representing an individual character. The Erligang culture exhibited a system of writing. Three bone artifacts with inscriptions were discovered, two with one character each, and one with ten characters. These artifacts appeared to be practice exercises in carving characters, marking a significant step forward in civilization.

The origin of primitive writing is an instinctive imitation of specific objects, which, though simple and chaotic, possesses a certain aesthetic taste. Thus, these early forms of simple writing can be considered prehistoric calligraphy.

Chinese calligraphy history

The evolution of calligraphy generally refers to the evolution of calligraphic styles. In general, the Wei and Jin dynasties were both a period of culmination and innovation in calligraphic techniques.

Chinese calligraphy has a long history, and its styles have evolved and changed over time, creating a captivating art form. From oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, the development of large seal script, small seal script, clerical script, and then the various scripts of cursive script, regular script, and running script during the Eastern Han, Wei, and Jin dynasties, calligraphy has always exuded a unique artistic charm.

From pictographic characters to oracle bone script, Shang, Zhou, Spring and Autumn, and the inked inscriptions on bamboo and silk in the Han dynasty, to the standardized Tang Kai script, the artistic pursuit of the Song dynasty, the emphasis on posture in the Yuan and Ming dynasties, and the calligraphic evolution during the Qing dynasty’s stone tablet controversy, calligraphy has undergone various transformations.

Shang to the end of the Qin dynasty

The systematic development of calligraphy

From the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, through the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, to the Qin and Han dynasties, over two thousand years of historical development have also driven the development of calligraphy. During this period, various calligraphic styles emerged, including oracle bone script, bronze inscriptions, stone carvings, and inked inscriptions on bamboo and silk. Among them, the five scripts of seal script, clerical script, cursive script, regular script, and running script were formed through the selection and elimination of hundreds of mixed scripts, marking the beginning of an orderly development of calligraphic art.

Qin Dynasty

Pioneering the art of calligraphy

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, there were significant differences in the written characters among the various states, which posed a major obstacle to the development of economy and culture. After the unification of the country by Emperor Qin Shihuang, Prime Minister Li Si was in charge of unifying the national script, which was a great achievement in Chinese cultural history. The script used after the unification of Qin was called Qin seal script, also known as small seal script, which was simplified based on bronze inscriptions and stone drum inscriptions. Among them, the inscriptions on Mount Yi, Mount Tai, Langya Mountain, and Kuaiji Mountain were written by Li Si and have been highly regarded throughout the ages. The Qin Dynasty was a period of inheritance and innovation. The “Preface to the Explanation of Characters” states, “There are eight scripts in the Qin Dynasty: Da Zhuan, Xiao Zhuan, Ke Fu, Chong Shu, Mo Yin, Shu Shu, Shu, and Li Shu.” This summarizes the appearance of the scripts of this period. Li Si’s small seal script in the Qin Dynasty was strict and inconvenient to write, leading to the emergence of clerical script. “Clerical script is the fast script of seal script.” Its purpose was to facilitate writing. In the Western Han Dynasty, clerical script completed the transformation from seal script to clerical script, with the structure changing from vertical to horizontal, and the strokes becoming more distinct. The emergence of clerical script was a great progress in Chinese calligraphy, marking a revolution in the history of calligraphy. It not only made Chinese characters tend towards a standardized form, but also broke through the single-centered stroke technique, laying the foundation for various calligraphic styles in the future. In addition to the above-mentioned calligraphic masterpieces of the Qin Dynasty, there were also various styles of official documents, weights and measures, brick inscriptions, and currency. Qin calligraphy left a brilliant page in the history of Chinese calligraphy, with its grandeur and pioneering spirit.

Eastern Han Dynasty

The pursuit of elegance and rhymes in Han calligraphy

Han calligraphy can be divided into two main forms: the mainstream system of Han stone inscriptions and the secondary system of wadang seal inscriptions and inked inscriptions on bamboo and silk. “Since the Later Han Dynasty, stone inscriptions and tablets have emerged in large numbers,” marking the maturity of Han clerical script. Among the cliffside inscriptions, the most famous are the “Shimen Song” and others, which are considered “exquisite works” by calligraphers. At the same time, Cai Yong’s “Xiping Stone Classics” achieved the requirements of restoring ancient clerical script, while Tai Xi Kai script reached the requirements of embryo regular script. Monumental inscriptions were the most important artistic form that reflected the spirit and rhyme of the times, with works like “Fenglongshan,” “Xixia Song,” “Kongzhou,” “Yi Ying,” “Shichen,” “Zhang Qian,” and “Cao Quan” being particularly admired and emulated by later generations. Each monument presented unique characteristics, with no two being alike. Northern calligraphy was magnificent, while southern calligraphy was ancient and simple, reflecting the different aesthetic pursuits of the “scholar” and “commoner” classes. As for wadang seal inscriptions and inked inscriptions on bamboo and silk, they represent the union of artistry and practicality.

The period of prosperity in calligraphic art began in the Eastern Han Dynasty. During this period, specialized theoretical works on calligraphy appeared, and the earliest proponent of calligraphy theory was Yang Xiong during the transition between the Eastern and Western Han dynasties. The first specialized book on calligraphy theory was Cui Yuan’s “Shuowen Jiezi Xu.”

Calligraphers of the Han Dynasty can be divided into two categories: Han clerical script masters, represented by Cai Yong, and cursive script masters, represented by Du Du, Cui Yuan, and Zhang Zhi.

The most representative features of Han calligraphy are found in stone inscriptions and bamboo slips and silk documents. The Eastern Han Dynasty saw a proliferation of stone inscriptions, and the stone inscriptions of this period were mainly carved in Han clerical script, with square and well-regulated characters, strict rules, and distinct strokes. During this time, clerical script had reached its pinnacle.

The Han Dynasty witnessed the birth of cursive script, which was of great significance in the history of calligraphy. It marked the beginning of calligraphy as an art form that could express emotions freely and showcase the individuality of calligraphers. The initial stage of cursive script was cursive clerical script, and during the Eastern Han Dynasty, cursive clerical script further developed into zhuancao, which was later established by Zhang Zhi as the current cursive script.

Three Kingdoms Period

During the Three Kingdoms Period, clerical script evolved into regular script (kaishu) from its peak in the Han Dynasty, and regular script became another major style in calligraphy. Regular script, also known as zhengshu or zhenshu, was created by Zhong Yao. It was during the Three Kingdoms Period that regular script began to be used in stone inscriptions. The “Jian Jizhi Biao” and “Xuanshi Biao” from the Three Kingdoms (Wei) period are regarded as precious treasures throughout the ages.

Jin Dynasty

In the Jin Dynasty, the pursuit of elegance and refinement in life and affairs, and the pursuit of moderation and simplicity in art, led to the emergence of numerous calligraphy masters. The artistry of bamboo slips and silk documents, particularly those of the Two Wangs (Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi), catered to the requirements of the literati, and people increasingly recognized that writing characters also had aesthetic value. This period best represents the spirit of the Wei and Jin dynasties. The most influential calligrapher of this period was Wang Xizhi, known as the “Sage of Calligraphy.” His running script masterpiece, “Lanting Preface,” is acclaimed as the “number one running script” and is characterized by its flowing and dynamic brushwork. His son, Wang Xianzhi, made significant contributions to calligraphy with his bold and vigorous style and the creation of the “broken style” and “one-stroke style.” Together with the contributions of calligraphic families such as Lu Ji, Wei Guan, Suo Jing, Wang Dao, Xie An, and Jian Liang, the southern school of calligraphy flourished. The calligraphy of Yang Xin of the Song dynasty, Wang Sengqian of the Qi dynasty, Xiao Ziyun of the Liang dynasty, and Zhi Yong of the Chen dynasty also followed in their footsteps.

The peak of calligraphic art in the Jin Dynasty was mainly manifested in running script, a script that lies between cursive script and regular script. The representative works are the “Three Xi”: “Boyuan Tie,” “Kuaixue Shiqing Tie,” and “Zhongqiu Tie.”

Northern and Southern Dynasties Period

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, calligraphy entered the era of Northern stone inscriptions and Southern brush scripts. The calligraphy of the Northern Wei Dynasty, which was similar to the Northern and Southern Dynasties’ stone inscription style, was the most outstanding. The term “Wei stele” refers to the calligraphy of the Northern Wei Dynasty and the stone inscriptions and stelae of the Northern and Southern Dynasties with a similar style. It was a transitional period in calligraphy from Han clerical script to Tang regular script. From the Jin Dynasty to the chaos of the Sixteen Kingdoms in the North, the power gradually declined. In the north, with the fall of the Western Jin Dynasty, a chaotic period known as the “Five Hu and Sixteen Kingdoms” emerged. The later Tuoba clan ended the Sixteen Kingdoms and established the Northern Wei Dynasty, leading to 149 years of relative unity, which was the Northern Dynasties period.

The calligraphy of the Northern Dynasties mainly focused on stone inscriptions, especially the Northern Wei and Eastern Wei dynasties, which had diverse and colorful styles. Representative works include the “Zheng Wengong Stele,” “Zhang Menglong Stele,” and “Jingshijun Stele.” This period was a transitional period from Han clerical script to Tang regular script. Kang Youwei said, “All Wei steles, when taken from one source, are sufficient to form a complete style. When combined, they are even more beautiful.” Zhong Zhisuai’s “Xuexuan Shupin” states, “The calligraphy of Wei steles reflects the old style of the Han and Qin dynasties, and reveals the style of the Sui and Tang dynasties.” In the early Tang Dynasty, prominent kaishu masters such as Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, and Chu Suiliang were all influenced by the Wei steles.

Tang Dynasty

The flourishing of calligraphy in the Tang Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty had a vast and profound culture, reaching the pinnacle of feudal Chinese culture. It can be said that “calligraphy reached its peak in the early Tang Dynasty.” Many calligraphic works from the Tang Dynasty have been preserved, surpassing previous periods in terms of quantity. A large number of stone inscriptions have left precious calligraphic works. The calligraphy of the Tang Dynasty both inherited and innovated upon the previous dynasties’ calligraphy. The development of regular script, running script, and cursive script in the Tang Dynasty entered a new realm, with distinct characteristics that have had a far-reaching impact on future generations.

In the early Tang Dynasty, with the country’s strength and prosperity, calligraphy emerged from the legacy of the Six Dynasties. The masters of regular script, such as Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, Xue Ji, and Ouyang Tong, were the mainstream of calligraphy. Their works were characterized by strict and neat structures, leading later generations to say that the Tang Dynasty emphasized the “Tang style of interlacing strokes.” They were highly regarded as the “crown of calligraphy.” Zhang Xu and Huai Su pushed the expression of cursive script to the extreme with their unconventional and dynamic styles. Zhang Xu was known as the “Crazy Sage” of cursive script, while Sun Guoting excelled in elegant cursive script. Other calligraphers such as He Zhi Zhang, Li Longji, and Wang Wenbing also made remarkable contributions, exploring new realms with their unique styles. Yan Zhenqing combined the ancient styles with innovative elements, creating a new style. Dong Qichang remarked that Tang Dynasty calligraphers drew from the methods of Lu Gong and made thorough preparations. In the late Tang and Five Dynasties period, as the national power declined, Shen Chuanshi and Liu Gongquan further transformed the style of regular script. They added a lean, forceful, and straightforward style, enriching the style of Tang regular script. During the Five Dynasties, Yang Ningshi adopted the strengths of Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan, combining their styles with his own unique approach. Wang Duo and Yan Zhenqing pursued vividness and capture of spirit, while expressing their emphasis on details, which brought new life to Tang Dynasty calligraphy. The influence of the “mad Zen” style was prominent during the Five Dynasties period, although it did not manifest on a large scale during that time, it had a significant impact on calligraphy in the Song Dynasty.

The art of calligraphy during the Tang Dynasty can be divided into three periods: Early Tang, Middle Tang, and Late Tang. The Early Tang period focused on inheritance, emphasizing adherence to established rules and seeking the vigorous beauty of calligraphy from the Jin Dynasty. During the Middle Tang period, calligraphy flourished with continuous innovation. Late Tang calligraphy also made progress.

The Tang Dynasty had six major academies, including the Guozijian (Imperial Academy), Taixue (Imperial College), the Four-Door School, the Lu School, the Shu School, and the Suanshu School. The Shu School specialized in nurturing calligraphers and calligraphy theorists, which was a unique initiative of the Tang Dynasty. Many renowned calligraphers emerged during this period, shining like stars. The early Tang Dynasty was dominated by calligraphy masters such as Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, and Chu Suiliang. The middle Tang Dynasty was represented by calligraphers such as Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan, who became calligraphic giants. Late Tang saw the emergence of masters like Wang Wenbing in seal script, Li E in regular script, and Yang Ningshi, who combined the styles of Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan to create a unique style.

The calligraphy of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties can be divided into three stages:

Sui to Early Tang:

During the Sui Dynasty, China was unified, and the culture and arts of the Northern and Southern Dynasties were encompassed. In the early Tang Dynasty, with political prosperity, calligraphy gradually emerged from the legacy of the Six Dynasties and began to show a new form. Kaishu (regular script) was the mainstream in the early Tang Dynasty, characterized by strict and orderly structures.

Flourishing Tang and Middle Tang:

During the flourishing Tang period, calligraphy reflected a romantic and unrestrained style, mirroring the social pursuit of a carefree and passionate lifestyle. Examples include the wild cursive script of Zhang Xu and Huaisu and Li Yong’s xingshu (semi-cursive script). In the middle Tang period, there were new breakthroughs in kaishu. Yan Zhenqing, as a representative figure, established the standard for kaishu, setting the orthodoxy. At this point, the various forms of Chinese calligraphy had been established.

Late Tang and Five Dynasties:

In 907 AD, Zhu Quanzhong overthrew the Tang Dynasty and established the Later Liang Dynasty, followed by the Later Tang, Later Jin, Later Han, and Later Zhou dynasties, collectively known as the Five Dynasties. Due to the weakened state and turmoil, cultural and artistic development declined. Although calligraphy continued from the late Tang Dynasty, the overall trend was in decline due to the influence of warfare and chaos. Notable calligraphers during this period include Yang Ningshi, who became a pillar of calligraphy during the Five Dynasties’ decline, as well as accomplished calligraphers like Li Yu and Yan Xiu. With this, the precise and rigorous calligraphic style of the Tang Dynasty gradually faded, giving way to the rise of the “Four Masters” of the Northern Song Dynasty and ushering in a new era.

Song to Mid-Ming:

Emphasis on Expression and Reasoning

During the Song Dynasty, calligraphy emphasized expression and reasoning. This was influenced by Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism, which advocated four aspects: philosophical thinking, scholarly elegance, stylistic characteristics, and expressive artistic conception. Calligraphy during this period reflected these aspects. If the preceding Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties period focused on the pursuit of technical skills (“gong”), the Song Dynasty presented calligraphy in a new light, emphasizing the expression of individual sentiments (“yi”). Song Dynasty calligraphers departed from the traditional Tang Dynasty kaishu style and directly inherited the aesthetics of Jin and Tang cursive script and semi-cursive script.

Whether it was the highly talented Cai Xiang or the innovative Su Dongpo, the reverent Huang Tingjian, or the unconventional Mi Fu, they all sought to express their own calligraphic style while exhibiting a unique approach. They infused their works with scholarly sentiments and brought forth a new aesthetic realm. This spirit was further extended by calligraphers in the Southern Song Dynasty such as Wu Shuo, Lu You, Fan Chengda, Zhu Xi, and Wen Tianxiang. However, their academic and calligraphic skills could not compare with the Four Masters of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Yuan Dynasty Calligraphy Art:

During the early Yuan Dynasty, there was limited development in terms of economy and culture. Calligraphy during this period largely adhered to traditional styles, following the Jin and Tang dynasties without much innovation. Although the Yuan Dynasty was politically ruled by an ethnic minority, it was culturally assimilated into Han culture. Unlike the Song Dynasty’s pursuit of unconventional aesthetics, the Yuan Dynasty emphasized meticulous craftsmanship and pursued an open, beautiful style. Su Shi advocated the idea of “my calligraphy is boundless,” while Zhao Mengfu emphasized the idea of “the brush technique should remain unchanged for eternity.” The former pursued free-spirited expression, while the latter emphasized intention in the art. The representative figure of calligraphy in the Yuan Dynasty was Zhao Mengfu, who established the standard for kaishu called “Zhao’s style,” alongside the Tang Dynasty’s Ouyang Xun, Yan Zhenqing, and Liu Gongquan. During the Yuan Dynasty, calligraphers such as Xian Yu Shu and Deng Wenyuan also achieved unique styles, even though their accomplishments were not on par with Zhao Mengfu.

Ming Dynasty Calligraphy Art:

The development of calligraphy during the Ming Dynasty can be divided into three stages:

Early Ming:

During the early Ming Dynasty, calligraphy emphasized uniformity, and the “Tai Ge” style prevailed. Shen Du and Shen Can, the two brothers, further promoted the refinement of xiaokai (small regular script). Their calligraphy was highly regarded in imperial examinations. Notable calligraphers of the early Ming Dynasty include Liu Ji, who excelled in caoshu (cursive script), Song Lao, who was skilled in xiaokai, and the famous Zhang Cao master Zhu Ke. The “Three Sons” – Zhu Yunming, Wen Zhengming, and Tang Yin – were also prominent calligraphers of this period.

Mid-Ming:

During the mid-Ming period, the Wu School of calligraphy emerged, and calligraphy began to develop towards a more elegant direction. Figures such as Zhu Yunming, Wen Zhengming, Tang Yin, and Wang Chong drew inspiration from Zhao Mengfu and the Jin and Tang dynasties, establishing their own unique styles and injecting a new vitality into calligraphy.

Late Ming:

In the late Ming period, there was a critical attitude towards calligraphy, and artists pursued large-scale works with visually striking effects. The brushwork became bold and expressive, with abundant ink splashes, creating an atmosphere of dynamism. Prominent calligraphers of this period include Zhang Ruitu, Huang Daozhou, Wang Duo, and Ni Yuanlu. However, Dong Qichang, known for his conservative stance, continued to advocate traditional principles.

Qing Dynasty:

Expression of Sentiment and Promotion of Reasoning

During the Qing Dynasty, calligraphy experienced a difficult transformation over a span of nearly 300 years. It broke free from the constraints of the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties’ orthodoxy and made significant achievements in seal script, clerical script, and the calligraphy of the Northern Wei steles, comparable to the kaishu of the Tang Dynasty, the xingshu of the Song Dynasty, and the caoshu of the Ming Dynasty. It formed a magnificent and profound calligraphic style. Particularly, calligraphers in the Qing Dynasty demonstrated a spirit of borrowing from the past to create new works and expressing individuality. The calligraphy scene thrived with diverse schools of thought. The orthodox tradition of the Qing Dynasty was dominated by the school of engraving, especially in the areas of seal script, li script, and the calligraphy of the Northern Wei steles. Renowned calligraphers during this period include Ruan Yuan, Bao Shichen, Kang Youwei, Jin Nong, Zhang Chuan, Liu Yong, and Zhang Yuzhao, who created calligraphy that achieved a balance between sentiment and reasoning, leaving a shining mark in the history of Chinese calligraphy.

Modern and Contemporary Period:

In today’s diversified calligraphy scene, the art has reached a level of conceptual transformation, which undoubtedly marks a significant step forward. The modernity of calligraphy does not solely rely on its external forms, structures, and lines, but rather on the modernization of its internal spirit. The modernity of calligraphy’s spirit refers to the values and tendencies of contemporary society conveyed and transmitted through modern calligraphic art.

In the modern and contemporary calligraphy scene, the tradition of the stele school still predominates. However, compared to the late Qing Dynasty stele school, there are more calligraphers in this period who draw inspiration from ancient steles and ancient seal and clerical script. Many calligraphy masters, such as Lin Sanzhi, Sha Menghai, and Lu Weizhao, were engaged in calligraphic creation before 1949 but gained recognition only in their later years, after the Cultural Revolution. From 1949 until the death of Mao Zedong, calligraphy was not highly valued as it was seen as representative of old traditions.

In the modern era, calligraphy has been characterized by a wide range of styles and a diverse community of calligraphers. The landscape of calligraphy during this period is more visible and distinct than ever before.

Chinese calligraphy in chinese new year

Calligraphy is a treasure of Chinese traditional culture, and the Spring Festival is the most solemn traditional festival of the Chinese people. There is a bridge between calligraphy and the Spring Festival, and that is the Spring Festival couplets. Without couplets, there is no Spring Festival, and with couplets, the festivity of the Spring Festival is enhanced. During the arrival of the Spring Festival, the unique scenery of writing, pasting, and appreciating couplets can be seen everywhere in the streets, alleys, and households, creating a magnificent spectacle. Therefore, some scholars believe that the Spring Festival couplets are an unparalleled and extraordinary literary and artistic activity in the world.

As a unique cultural activity, writing Spring Festival couplets has a long history and a profound mass foundation. In the late Five Dynasties, the relationship between Spring Festival couplets and ancient peach charms was revealed. In ancient times, drawing totems and hanging peach charms were a folk belief in worshipping heaven and ancestors and praying for blessings and auspiciousness. With the development of society and the changes of the times, drawing totems and hanging peach charms were gradually replaced by pasting New Year paintings and Spring Festival couplets.

It is generally believed that the custom of writing Spring Festival couplets in Chinese folk culture originated in the late period of the Five Dynasties. Mr. Liang Zhangju, a scholar of the Qing Dynasty, pointed out in his book “Talks on Couplets” that the earliest Spring Festival couplets in China were written by Meng Chang, the later emperor of the Shu Kingdom in the Five Dynasties, with the phrase “New Year receives surplus celebrations, auspicious festival named Changchun.” However, Mr. Liang Zhangju himself held a cautious attitude towards this and stated, “It is unknown whether there is any evidence before this.” However, from the parallel prose and elegant writings of literati and scholars in the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, it can be seen that Spring Festival couplets were only popular among the upper class society at that time. The evidence that Spring Festival couplets “entered the homes of ordinary people” can be found in Wang Anshi’s poem “Yuan Ri”: “In the sound of firecrackers, a year is ushered in, and the spring breeze brings warmth to the herb liquor. Thousands of doors and households are filled with the glow of the sun, all replacing the old charms with new peaches.” From the poem, it can be seen that Spring Festival couplets were widely spread across different levels of society.

An important contribution to the development of Spring Festival couplets was made by Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty. He had a deep love for couplets and not only wrote them himself but also encouraged his ministers to write them. The “Miscellaneous Records of the Zanyun Building” records that one New Year’s Eve, he ordered, “Officials and noble families must add a pair of Spring Festival couplets to their doors.” On the first day of the lunar year, Zhu Yuanzhang disguised himself and went on an inspection tour. When he saw Spring Festival couplets on the doors of every household, he felt extremely happy. When he arrived at a household that didn’t have couplets on their door, he asked why. It turned out that the homeowner was a butcher who couldn’t read or write and was busy making a living during the New Year period, so he didn’t have time to paste Spring Festival couplets. Zhu Yuanzhang immediately picked up a brush and wrote a pair of couplets for that household. The couplets read, “With both hands, open the road of life and death; with one knife, sever the root of right and wrong.” The humorous and profound meaning of the couplets quickly became a popular topic. From this story, we can see Zhu Yuanzhang’s strong advocacy for Spring Festival couplets. It is said that the official naming of the term “Spring Festival couplets” began with Zhu Yuanzhang. Since then, the custom of pasting Spring Festival couplets during the New Year has been passed down to this day, thriving and enduring. “Two sisters, equally tall; dressed alike, each with her own style; faces glowing with joy, bringing good fortune year after year.” This riddle about Spring Festival couplets is well-known and widely understood in China, reflecting the characteristics of Spring Festival couplets being appreciated by both the refined and the popular, loved by young and old alike, and also reflecting the deep social and mass foundation of Spring Festival couplets. With the new year, all things are renewed; with the pasting of Spring Festival couplets, joy and happiness abound. The custom of pasting Spring Festival couplets fills the land of China with a festive atmosphere of “red and lively, blessings overflowing the door, joyfully celebrating the New Year” during the Spring Festival.

is Chinese calligraphy still used today?

Yes, Chinese calligraphy is still widely practiced and appreciated today. It has a long and rich history in China, dating back thousands of years, and it continues to be an important art form and cultural tradition.

Chinese calligraphy is highly regarded for its aesthetic beauty and expressive qualities. It involves the skilled use of a brush, ink, and paper to create characters and artistic compositions. Calligraphy is considered one of the highest forms of visual art in Chinese culture and is deeply intertwined with the country’s language, literature, and philosophy.

In contemporary China, calligraphy is practiced by both amateurs and professional artists. Many people learn calligraphy as a hobby or as part of their cultural education. It is taught in schools, and there are calligraphy clubs and associations where enthusiasts gather to study and practice together. There are also numerous exhibitions, competitions, and cultural events dedicated to calligraphy.

Moreover, Chinese calligraphy has extended its influence beyond China’s borders and has gained popularity worldwide. It is appreciated by people from diverse cultural backgrounds for its elegance and unique artistic expression. Many international museums and art institutions feature exhibitions and collections dedicated to Chinese calligraphy, further showcasing its enduring relevance in the modern world.

what is common between the Chinese and japanese calligraphy?

Chinese and Japanese calligraphy share a common origin and have influenced each other throughout history. Here are some key similarities between Chinese and Japanese calligraphy:

Origins: Japanese calligraphy has its roots in Chinese calligraphy, which was introduced to Japan during the 5th and 6th centuries. The Japanese adopted Chinese characters, known as kanji, and the techniques of calligraphy from China.

Brush and Ink: Both Chinese and Japanese calligraphy utilize similar tools, such as brushes and ink. The brush is typically made of animal hair, such as goat or wolf, and the ink is traditionally made from soot or ink sticks that are ground with water on an inkstone.

Writing System: Chinese characters (hanzi) are used in both Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. While the basic characters are the same, the two languages have developed their own set of characters and writing conventions over time.

Stroke Order: Both Chinese and Japanese calligraphy emphasize the correct stroke order when writing characters. There are specific rules and guidelines for how each stroke should be executed, including the direction, pressure, and rhythm.

Aesthetic Principles: Chinese and Japanese calligraphy share similar aesthetic principles, such as balance, rhythm, and harmony. Both traditions value the expressive qualities of brushwork, including variations in thickness and speed.

Artistic Expression: Both Chinese and Japanese calligraphy are considered forms of artistic expression. They go beyond mere writing and are appreciated for their visual beauty and the emotions they convey.

Despite these similarities, there are also distinct differences between Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. Japanese calligraphy has developed its own unique styles and techniques, and it has been influenced by Japanese culture and aesthetics over the centuries. It is important to recognize and appreciate the individual characteristics of each tradition while acknowledging their shared heritage.

Famous Chinese Calligraphy Artists

The art of Shufa has been practiced for many years in Chinese culture. Over time there have been many famous and notable Chinese calligraphers. The following are a few of them:

Huang Tingjian

Huang was from the Song dynasty. He was majorly known as a calligrapher although he was also a poet, scholar, and government official. Many people admired his work, which was mostly influenced by his older friend’s literati paintings.

Ouyang Xun

Born during the Tang dynasty into a family of government officials, Ouyang was a calligrapher and cultured scholar. He was among the great calligraphers of his time, especially famous for his regular script known as Ou Style. He was also very proficient in Chinese classics.

Zhang Zhi

Zhang is among the four greatest calligraphers who were born during the Han dynasty. He is said to be the pioneer of modern cursive script, as such he was honored as the sage of Cursive script.

Mi Fu

Mi was also a calligrapher from the Song dynasty. Although he was also a poet and painter, he was most famous for his calligraphy. He was actually among the four greatest calligraphy in the Song dynasty. He was also nicknamed Madman Mi because he had the habit of collecting stones considering them his brothers.

Wang Xizhi

Also known as the sage of calligraphy, Wang is considered to be the greatest calligrapher in history, who lived in the Jin dynasty. He was a master of every writing form including the running script. Even his signature was said to be priceless.

Zhong Yao

Also known as Yuanchang, Zhong was a calligrapher and government official who served in the Eastern Han dynasty during the Three Kingdoms period. He is also considered to be among the four greatest calligraphers in history.

Conclusion

As with all art, the fundamental inspiration for Shufa is nature. A finished piece is not simply the asymmetrical arrangement of shapes, but almost like beautifully coordinated dance movements. Although Chinese calligraphy may seem intimidating to attempt, given the seriousness, there is no big mystery to it. The art requires simple tools including a brush, inkstone, ink stick, and paper or silk. Other than that, you need your imagination and technical skill, which is what requires years of practice to master.

Reference: Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China.

Hi, I do believe this is a great website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may revisit once again since I book-marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide other people.