China’s Sui Dynasty takes pride in being the most famous dynasty that played a critical role in unifying China to be one rule, especially at a time when the country was in disarray after what is known as the Period of Disunion. And though the Sui Dynasty ruled for a rather short period, between 581 and 618AD, before its replacement by the infamous Tang Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty still played a huge historical role.

There is a lot that the Sui Dynasty is known for, and this article shares insights into everything you should know about the Sui Dynasty.

what is the Sui Dynasty?

The Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD) was a significant unified dynasty in Chinese history that bridged the gap between the Southern and Northern Dynasties and paved the way for the subsequent Sui Dynasty. It lasted for thirty-seven years and played a crucial role in ending nearly three centuries of fragmentation since the late Western Jin Dynasty.

Emperor Wen of Sui, Yang Jian, proclaimed the dynasty and established its capital in Daxing City (present-day Xi’an, Shaanxi Province). In the year 589 AD, the Sui forces conquered the Chen Dynasty in the south, bringing about the reunification of China and putting an end to the prolonged division that had persisted since the decline of the Western Jin Dynasty.

Emperor Yang of Sui, Yang Guang, ascended the throne and constructed the Eastern Capital (modern-day Luoyang, Henan Province), as well as the Grand Canal that connected the northern and southern regions. However, these endeavors placed a heavy burden on the state’s resources and led to the outbreak of rebellions towards the end of the Sui Dynasty. In 618 AD, a military uprising led by figures like Yuwen Huaji resulted in the death of Emperor Yang of Sui. Li Yuan compelled Yang You to abdicate, and the Sui Dynasty was established with its capital in Chang’an. In 619 AD, Wang Shichong forced Yang Tong to abdicate, establishing the Zheng Dynasty and marking the final downfall of the Sui Dynasty.

why was it called the Sui Dynasty?

The origin of the name of the Sui Dynasty is as follows:

During the Northern Zhou period, Yang Jian inherited his father’s title and became the Duke of Sui. When he proclaimed himself emperor, he found the character “辶” in the word “随” to be unstable and inauspicious, so he removed “辶” and created the character “隋” to be the name of the dynasty. This new character had a different meaning and pronunciation from the previous “随,” and it became the formal name of the Sui Dynasty.

how was the Sui Dynasty founded?

Emperor Xuan of Northern Zhou indulged in extravagance and luxury, immersing himself in wine and pleasure while presiding over a corrupt administration. He even self-proclaimed as the “Heavenly Emperor of the Prime Beginning” and had a total of five empresses, including his own daughter, Yang Lihua, who was married off as an empress. Taking advantage of this situation, Yang Jian, a prominent figure among the imperial relatives, gradually sidelined influential officials and gained control over the government.

In the second year of Dàxiàng (580 AD), after the death of Emperor Xuan of Northern Zhou, Yang Jian, who held a leading position among the Guanlong aristocracy, allied with Liu Fang and Zheng Yi to manipulate imperial decrees and assert power as an imperial relative.

In the first year of Dàdìng (581 AD), in the month of February, Emperor Xuan of Northern Zhou abdicated the throne in favor of Yang Jian, who then changed the dynasty’s name to Sui. Yang Jian became Emperor Wen of Sui, with the capital established in Daxing City (modern-day Xi’an, Shaanxi Province). This marked the downfall of the Northern Zhou Dynasty.

How Did the Sui Dynasty Reunify China?

The process by which the Sui Dynasty unified China involved the conquest of Western Liang, the annexation of Southern Chen, and the pacification of regions such as Jiangnan and Lingnan:

Conquest of Western Liang: In the year 587, Yang Jian summoned the Emperor of Later Liang, Xiao Cong, to Chang’an and dispatched troops to capture Jiangling, thereby abolishing the state of Liang.

Annexation of Southern Chen: In October of 588, Yang Jian established the Huainan Administration in Shouchun and appointed Yang Guang, the Prince of Jin, as Minister of the Left, responsible for the campaign against Chen. Later, Yang Guang, along with Yang Jun, the Prince of Qin, and Yang Su, the Duke of Qinghe, were appointed as commanders. A total of ninety commanders led an army of 518,000 soldiers under the command of Yang Guang. In January of 589, Heruo Bi and Han Qinhu successfully crossed the Yangtze River, facilitating the passage of the Sui army.

Pacification of Jiangnan and Lingnan: Following the conquest of Chen, the Sui Dynasty initiated significant reforms according to Sui’s governance principles. In the tenth year of Emperor Wen’s reign (590 AD), a rebellion erupted from the southern bank of the Yangtze River to Quanzhou (located in modern-day Fujian’s Jinjiang County) and further south to Lingnan. Local gentry and landlords rose in revolt. Sui dispatched General Yang Su to lead an expedition, ultimately retaking Quanzhou and swiftly quelling the uprisings in Jiangnan. A few ethnic leaders in Lingnan instigated further uprisings, laying siege to Guangzhou. Sui sent Pei Ju with a force of three thousand troops, along with Xian Furen of the Gao Liang commandery (located west of Yangjiang County in Guangdong), to pacify the various ethnic leaders in Lingnan.

This comprehensive effort of conquest, annexation, and pacification marked the process through which the Sui Dynasty achieved the unification of China.

Sui Dynasty Achievements Timeline

Here is the timeline of the Sui Dynasty:

581: Emperor Wen of Sui (Yang Jian) accepts the abdication of Northern Zhou and establishes the Sui Dynasty.

583: The Sui Dynasty relocates its capital to Daxing City.

589: The Sui Dynasty conquers Southern Chen, unifying China.

604: Emperor Yang of Sui (Yang Guang) ascends the throne.

605: Qibi Heli Khan, of the Tiele tribe under Western Turkic Khaganate, becomes Yiwu Zhenhen Khan and establishes dominance over the Tian Shan region. He dispatches officials to Gaochang (Karashahr) for taxation on trade with merchants.

607: Emperor Yang visits the yurt of Qimin Khan, situated in the southern desert.

608: Emperor Yang sends Pei Shiqing as an envoy to the Wa country (Japan). Gao Xiangxuan and others from Japan travel to the Sui Dynasty for studies.

609: Emperor Yang leads a campaign against the Tuyuhun.

610: The Sui Dynasty captures Yiwu (Hami).

612-614: The Sui Dynasty launches three failed expeditions against Goguryeo.

614: Sushen Hu, a Sogdian within East Turkic Khaganate, falls victim to a scheme orchestrated by Sui statesman Pei Ju and is lured to the mutual market at Mayi (Shuozhou) and killed.

615: Dongdan Beg Khan of East Turkic Khaganate leads his forces southward, invading the western part of the Datong Basin. Emperor Yang’s campaign in the vicinity of Yanmen is surrounded by Turkic forces, resulting in a difficult situation.

617: Li Yuan rises in rebellion in Taiyuan, marching south to Chang’an. He proclaims Emperor Yang’s grandson, Yang You, as the King of Tang, while establishing his own power as the Duke of Tang. Li Gui establishes a regime in Liangzhou (Wuwei).

618: Emperor Yang is assassinated by his subordinates in Yangzhou (Jiangdu). Li Yuan establishes the Tang Dynasty, adopting the era name of Wude.

Sui Dynasty Timeline

As mentioned above, the Sui Dynasty was not in leadership for a very long time, but during their time, they did some incredible things. Their short timeline is as follows:

581-618 – Sui Dynasty rules China.

- 581 – 601 – The first emperor of the Sui Empire, Wen (Wendi), ruled China

- c.607 – Japan’s prince, Prince Shutoku, sends a number of Japanese officials to Sui China’s embassies

- 612 – General Eulji Mundeok of Goguryeo wins a huge victory against the Sui empire at the Salsu River battle.

- 604 – 618 – The second and last Sui Emperor, Yang, ruled China.

Although Sui Dynasty’s reign was rather brief and only had one successful emperor that led for a significantly long time, this dynasty was able to successfully unify China after the split of the Northern and Southern dynasty periods. Though short-lived, the Sui dynasty made impactful structural changes that have since paved the way to even more long-lasting successors and national success. The Sui dynasty set a good system that would ensure flourishing arts and culture scenes.

There also were reforms in the government, and these reforms would also affect the civil administration, as well as the laws on land distribution, consequently helping to ensure the restoration and the centralization of the imperial authority. On the flip side, this regime was infamous for its high immorality levels, the very expensive public spending projects, as well as well as military follies. And combined, these brought in a strong rebellion that would ultimately result in the Sui dynasty being overthrown. The Sui dynasty had its capital in Daxing, whose name was changed to Chang’an during the reign of the Tang Dynasty. Today this city is known as Xi’an.

When Did the Sui Dynasty Start and End?

The Sui Dynasty of China began in the year 581 AD when Emperor Wen of Sui (Yang Jian) established the dynasty by taking the throne. The Sui Dynasty came to an end in the year 618 AD following the death of Emperor Yang of Sui (Yang Guang) and a series of uprisings and revolts. The Sui Dynasty lasted for a total of 37 years.

Why Did Sui Dynasty End?

The fall of the Sui dynasty was a result of the big losses suffered. These losses were caused by the military’s failure in their campaigns against the Goguryeo, and after too many defeats and losses, the country was left in ruins, with the rebel forces taking over control of the government. Sui dynasty’s last emperor, Emperor Yang, was assassinated in the same year that the dynasty ended in 618.

Sui Dynasty Emperors List

Sui Dynasty only had two Emperors, Emperor Wen, who ruled between 518 and 605, and Emperor Yang, who ruled between 604 and 618.

These emperors also contributed a great deal to the unification of China. It’s worth noting that towards the end of the 6th Century CE, China was faced with warring states that were often vying for greater power and wealth, which means that they were always at loggerheads with each other. These conflicts led to 3 centuries of endless conflict and disunity that would only come to an end in 581CE after the commander known as Yang Jian/ Yang Chien who was able to seize the government off from the hands of the military base that was at Guangzhou at the time, unifying the North as a result.

Notably, Jian was not just one of the most talented generals, but he was also quite connected, especially after his daughter got married to the Northern Zhou dynasty’s heir, a move that earned him a huge imperial connection. After the demise of this heir in 580CE, Jian took this opportunity to declare himself as a regent and to make sure that there would be no rebellion or rivals to knock him off his course and the newly acquired throne; Jian had up to 59 of the members of the royal Zhou family murdered. He then set his sights on the south by 588CE.

One of the first things he did was name his newly acquired state, the state of Sui – this is a name that he took after his father’s fiefdom. In recent days/ months, Jian was able to amass more than 500,000 people to his army, and he also had a huge fleet, including a 5-decked ship with the capacity to carry at least 800 men. Thanks to these resources, Jian sailed down the famous Yangtze River, sweeping all men that stood in his way, and in 3 months, he’d captured Nanjing. And by 589CE, he’d won over the South. And just like that, China was, once again, a single state, with Chang’an as its capital, and Jian would consequently be the emperor of Sui, taking on the name Emperor Wendi. He then established his dynasty that was run as one China.

His biggest contributions include the building of the Great Wall of China; he encouraged the launching of the War on Vietnam, the Construction of the Grand Canal, the Unification of China, the Spread of Confucianism, and the adoption and spread of Buddhism, among others.

The second and last emperor of the Sui dynasty, Emperor Yangdi, came into power in 604, and during his reign, he ensured that the integration of Southern China into the empire was complete. He further encouraged and emphasized the Confucian classics, especially for the examination system for people looking for public employment. He also built the second China capital in the East in Luoyang while remaining engaged in the large construction projects that had been started, which included the vast canal system.

list of sui dynasty emperors

Here is the list of emperors of the Sui Dynasty:

Emperor Wen of Sui, Yang Jian (July 27, 541 – August 13, 604), reigned from March 4, 581, to August 13, 604.

Emperor Yang of Sui, Yang Guang (569 – 618), reigned from August 13, 604, to 618.

Emperor Gong of Sui, Yang You (605 – 619), reigned from 617 to 618.

Crown Prince Hao of Sui, Yang Hao (586 – 618), reigned in 618.

Crown Prince Dong of Sui, Yang Tong (604 – 621), reigned from 618 to 621.

Sui Dynasty Achievements And Inventions

The biggest achievements and contributions made by the Sui dynasty to China include the unification of China into one nation, once again ending the Northern and Southern China empires. This dynasty was also behind the constructions of the Great Wall and the Grand Canal and a host of other achievements that have really reformed China.

- Consolidated Control and Great Administrative Reforms

The Sui dynasty unified China and also expanded the nation’s territory. But perhaps one of their biggest achievements is their creation and policing of a more improved and largely centralized system of administration featuring unified, single, and less complex laws and codes. They also introduced lasting land reforms.

The system of administration for the empire had the old Nine-Rank System abolished, and this system was replaced by local prefects that were selected on the basis of merit, as demonstrated by their performance in the Confucian-based civil service examinations that were only done at the capital. The selected officials would then be sent out to different provinces other than the provinces that they were born into – a move that reduced corruption and nepotism.

The empire also came up with the Equal Field System (previously introduced by the 5th Century CE emperor Xiaowen). This system was applied by the Sui dynasty, and the small farmers were protected from being swallowed by the large estates.

- Construction of the Grand Canal

After making Luoyang the dynasty’s capital, Emperor Wen would kick off the construction of the Grand Canal to ensure the development of the new capital. Though he didn’t finish it, his son, Yang Guang, continued works on the canal, seeing it to completion. Millions worked on the projects, and many of these hard-working laborers died from the bad conditions (malaria ravaged the laborers) and the hard labor, unfortunately.

The construction of the Canal is considered one of the biggest engineering achievements. The canal runs from Hangzhou all the way to Beijing, and it turned into the best and the quickest means of transport that would transport resources needed for the war launched against Goguryeo. The subsequent ease of transportation/ travel further encouraged the prosperity of the Sui and Tang Empires. Note that the Grand Canal of China is the longest canal an artificial river in the world.

- Rebuilding the Great Wall of China

Even before becoming the Emperor, Jian had started work on the reconstruction of the Great Wall located north of the kingdom. After he was the emperor, he ensured that the sections of the wall were rebuilt. The construction of the Great Wall stretched into the inner parts of Mongolia. But just like the work on the canal, many laborers died in this project. This wall was the most notable point of defense for Sui China against the Tujue (Eastern Turks).

- Encouraged/ Supported the spread of Buddhism.

The Sui empire/ dynasty is also known for the support they showed religion and the fact that they supported the growth and the spread of Buddhism. This is believed to be the case because Emperor Wen was Buddhist, and during his time, Mahayana Buddhism became more popular. He even passed an Edict in 601 that said that all the people of the 4 seas would, without any exceptions, develop enlightenment while also cultivating fortunate karma and bringing to pass-happy existences and future lives. And that creating good things would carry the believers towards a higher level of enlightenment.

- Encouragement of Confucianism

This is the other belief system that was encouraged by the Sui dynasty, especially because of the increasing number of educated bureaucrats that ruled the Western Han empire, all of who believed in the philosophical teachings associated with Confucianism. The Confucian education system was also adopted, and individuals interested in working in public offices were required to learn and undertake the Confucian examinations for any administrative roles.

The spending by the dynasty was quite high, though. And along with the immoral levels associated with the dynasty, it makes sense (in hindsight) that the Sui dynasty didn’t last too long.

Why Did the Sui Dynasty End?

The downfall of the Sui Dynasty can be attributed to several factors:

- Emperor Yang of Sui’s dissatisfaction with other power factions, coupled with his suppression of small interest groups, undermined their interests and led to multiple conflicts and chaos.

- The common people and peasants despised Emperor Yang’s rule as a tyrant, leading to uprisings fueled by their deep-seated resentment. These uprisings contributed to the disintegration and ultimate collapse of the once powerful Sui Dynasty.

- The excessive influence of powerful aristocratic families in the Sui Dynasty resulted in Emperor Yang’s orders often being ignored or circumvented.

- Emperor Yang’s extravagant expenditures, coupled with his extensive military campaigns, led to severe depletion of human, material, and financial resources. This economic strain contributed to the outbreak of rebellions known as the “Rebellion at the End of Sui.”

These combined factors contributed to the downfall of the Sui Dynasty, leading to its fragmentation and eventual demise.

Sui dynasty political structure

Centralization:

After Emperor Wen of Sui ascended the throne, he abolished the official system established by the Northern Zhou dynasty based on the “Rites of Zhou” and introduced a new system of governmental positions. This new system included the establishment of the Three Masters, Three Excellencies, as well as ministries such as the Ministry of Personnel, the Palace Secretariat, the Ministry of Interior, the Bureau of the Imperial Secretariat, the Imperial Attendants, and more. Additionally, it encompassed institutions like the Imperial Censorate, the Ministry of Rites, the Ministry of Appointments, the Ministry of Justice, the Bureau of the Imperial Clan, the Ministry of Finance, the Imperial Academy, and the Bureau of Royal Works, along with offices like the Left and Right Guards, and the Left and Right Military Guards. This reorganization aimed to strengthen central authority and revive the traditional administrative system of the Han ethnic dynasty. The Three Departments and Six Ministries, consisting of the Ministries of Personnel, Palace Secretariat, and Interior, formed the core of the Sui Dynasty’s central administrative structure. The Three Masters and Three Excellencies held high status and ranks, but their roles were largely honorary. Notably, the Ministry of Personnel held a particularly prominent position during the Sui Dynasty, described as having “unlimited authority” in the “Book of Sui · Records of Officials,” reflecting its status as the highest national administrative institution with significant power.

Political Reforms:

Emperor Yang of Sui, in his pursuit of political reform centered around the system of noble titles and meritorious officials, aimed to break away from the “Guanzhong-centric policy” implemented since the reign of Yuwen Tai in the Northern Zhou dynasty. He sought to limit and weaken the influence of the Guanlong clique, thereby streamlining governance, strengthening central authority, and broadening the foundation of rule within society. However, the hasty and immature implementation of his political reform measures failed to integrate with the establishment of a smooth, united, and stable political landscape. This ultimately led to a severe crisis in governance.

Imperial Examination System:

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties, the idea of selecting useful talent through examinations, such as “ju ming jing,” had emerged. However, the “Nine-Rank System of Imperial Officials” that had been in place since the Wei and Jin dynasties continued to be enforced. In the seventh year of Emperor Wen’s reign (587 AD), Sui Dynasty officially established the system of subject-specific examinations, replacing the Nine-Rank System. From then on, selection of officials was no longer based on social status. This early version of the imperial examination system required each province to send three candidates annually to participate in the examinations for xiucai (literary talents) and mingjing (classics). In the second year of the Daye era (606 AD), Emperor Yang further established the jinshi (advanced scholar) examination, solidifying the imperial examination system. The subjects tested included strategy for the xiucai examination, current affairs policies for the jinshi examination, and classical texts for the mingjing examination. This system marked the beginning of the imperial examination system, although it still differed from the fully developed system of the Tang dynasty. The xiucai examination, while not highly effective in selecting talent, helped to break the monopoly of noble families over official positions. This system catered to the political aspirations of various local aristocrats and landowners over the years, mitigating conflicts with the central government and fostering their loyalty. It also contributed to talent recruitment and enhanced political efficiency, playing a positive role in strengthening central authority.

Legal System:

The legal system of the Northern Zhou dynasty was characterized by fluctuating severity, leading to confusion in sentencing. After Emperor Wen’s accession in the first year of the Kaicheng era (581 AD), he ordered officials including Gao Feng to refer to the legal codes of the Northern Qi and Northern Zhou dynasties, resulting in the establishment of legal codes. In the third year of the Kaicheng era (583 AD), Su Wei and others were tasked with revisions, leading to the completion of the “Kaicheng Code.” Based on the Northern Qi’s “Heqing Code” and incorporating elements from the legal codes of the Northern Zhou and Southern Liang dynasties, the “Kaicheng Code” simplified legal provisions, drawing upon the strengths of both northern and southern legal systems. It was renowned for its concise and effective nature, setting strict penalties for heinous crimes. The “Kaicheng Code,” consisting of twelve scrolls and five hundred articles, categorized punishments into five types and twenty levels: death penalty, exile, penal servitude, flogging, and caning. It abolished brutal punishments such as flogging, decapitation, and dismemberment, serving as the foundation for legal codes in subsequent dynasties, including the Tang dynasty.

Sui dynasty economic structure

Agriculture:

During the Sui Dynasty, Emperor Wen implemented the Equal Fields System (Lingjun Tian Ling) and reorganized household registration. This system introduced frequent population checks by officials using a method known as “Da Suo Mao Yue” that examined people’s appearances to assess their household status, resulting in a significant increase in registered households. Building upon the concept of “Shu Ji Ding Yang,” the government established a fixed number of households based on the initial census, creating a “Ding Bu” (census register) to determine tax collection. The Sui Dynasty also constructed numerous granaries across various regions, including well-known ones like Xingluo Granary, Huiluo Granary, Changping Granary, Liyang Granary, and Guangtong Granary. These granaries collectively stored over a million stone (a unit of volume) of grain. Even after 20 years of the Sui Dynasty’s demise and 33 years since Emperor Wen’s death, grains and fabrics stored during that period remained unutilized. In 1969, an excavated Sui Dynasty granary site called Hanjia Granary was discovered in Luoyang, covering an area of over 450,000 square meters and containing 259 granaries, with one containing 500,000 jin (a unit of weight) of carbonized grain. These findings attest to the prosperity and strength of the Sui Dynasty.

Handicrafts in the Sui Dynasty:

The Sui Dynasty marked an important stage in the development of Chinese porcelain production technology. Notably, excavations in the tombs of Anyang in Henan and Xi’an in Shaanxi revealed a collection of white-glazed porcelain artifacts. Known as “Zhaobei White Porcelain,” these artifacts exhibited firm texture, translucent luster, and aesthetically pleasing forms, representing an early instance of white porcelain in China. Additionally, green-glazed porcelain production was widespread during the Sui Dynasty, with artifacts unearthed in regions such as Hebei, Henan, Shaanxi, Anhui, and Jiangnan. Numerous Sui Dynasty kiln sites were discovered, particularly in the economically developed Jiangnan region. The advancement of porcelain craftsmanship during the Sui Dynasty contributed to overall economic growth during that period.

Sui Coinage:

Chang’an not only served as the political and economic center of the nation but was also an international metropolis. The city’s remarkable size and commercial vitality made it rare on the global stage during that era. The Sui Dynasty unified the currency system, abolishing various antiquated and privately minted coins, and introduced the “Sui Wu Zhu” or “Five Zhu” coin. These coins had a distinctive design on the reverse side, featuring a raised border and inscriptions with a weight of four jin (a unit of weight) per thousand coins. Under Emperor Wen’s reign, standard units of measurement and weights were also unified. This period of unification brought together learned figures from various previous dynasties, creating a compilation of knowledge and culture. Furthermore, Yang Jian (Emperor Wen) enacted benevolent policies such as exemptions from corvée labor and tax for individuals over fifty years of age and providing one year of support for families of soldiers who died in battle.

Sui dynasty coins(Currency of Sui Dynasty)

Due to the Sui Dynasty having only two emperors, there are also only two types of Sui Five Zhu coins:

Kaihuang Wuzhu (开皇五铢): These were minted during the reign of Emperor Wen from the sixth year of the Kaihuang era to the fourth year of the Renshou era (581-604 AD). These coins, also known as “Sample Five Zhu,” were exquisitely crafted, with varying sizes and weights. Standard coins were typically around 2.5 centimeters in diameter and weighed approximately 3.0-3.4 grams, while smaller ones had a diameter of about 2.3 centimeters and weighed around 2.25-2.3 grams. The face of the coin featured seal script with the character “五” (five) written horizontally, and a vertical line was cast to the right of the perforation hole. The reverse side also had a raised rim. These coins were lightweight and required around 80,000 to 90,000 pieces to fill a measurement called a “米斛.”

Baiqian Wuzhu (五铢白钱): White coins minted during the reign of Emperor Yang, in the Deyuan era (605-618 AD), are known as “Baiqian Wuzhu.” These coins had a vertical line on the left side of the character “五” on the obverse face. When rotated, this line could resemble the character “凶” (ominous), leading to the name “凶钱” (ominous coin). During Emperor Yang’s reign, due to extensive construction projects and a lack of copper mines, the official mints introduced tin and lead into the coin-making process to reduce costs. As a result, the coins had a white appearance, leading to their designation as “白钱” (white coin). The massive production of these white coins contributed to currency devaluation and was a significant factor in the downfall of the Sui Dynasty.

In addition to the Sui Five Zhu coins, various types of coins from preceding dynasties were also widely circulated. Notable examples include:

Liang Zao Xin Quan: Minted during the Western Liang dynasty (317-376 AD) under Zhang Gui’s reign, this coin had a square hole and circular shape, with variations in weight and size.

Tai Qing Feng Le: Minted during the Taiqing era of the Southern Liang dynasty, these coins featured refined inscriptions and a distinctive arrangement of characters.

Zou Yu Zhi Qian: Minted during the Sui Dynasty, these coins featured the characters “驺虞” in a combination of regular and seal scripts, with an appearance similar to the Changping Wuzhu but with a less harmonious design.

tribute system Sui dynasty(diplomacy)

During the Sui Dynasty, in its foreign relations, it advocated a tributary system where various vassal states recognized Sui China as the suzerain power. These vassal states regularly presented tributes, and peaceful coexistence was maintained among them. In cases where a country refused to submit, the Sui Dynasty would resort to warfare to subjugate them if necessary. If one country invaded another, the Sui Dynasty would assist the weaker nation to defeat the aggressor, all in the interest of upholding the tributary system. Submissive vassal states received favorable rewards from the Sui Dynasty. This diplomatic philosophy led to a grand scene of nations coming to pay tribute. However, Emperor Yang of Sui excessively boasted about these achievements, leading to wastage of resources and manpower.

In the northern regions, the Tujue Khanate emerged as a powerful entity in the northern and central Asia after overthrowing the Rouran Khaganate. Many northern states offered tributes to the Tujue Khanate. Yet, after the death of Kaghan Tuobo, the Tujue Khanate fell into turmoil, leading to the emergence of five khans: Shabolü Khan as the Great Khan, Shilun Khan as the Second Khan, Daluobi Khan as the Apo Khan, and Chuluo Khan as the Datou Khan. In 583, due to the cessation of tributary payments from the Sui Dynasty and the request of Princess Qianjin of the Northern Zhou Dynasty, Shabolü Khan launched a southern invasion, known as the Sui-Tujue War. Through multiple battles, Emperor Wen of Sui defeated the Tujue forces and strategically orchestrated the division of the Tujue Khanate into Eastern and Western Tujue. In 599, the Eastern Tujue Qimin Khan was defeated and surrendered to Sui, and in 611, the Western Tujue Nili Khan also surrendered, temporarily alleviating the Tujue threat.

In 605, the Sui general Wei Yunqi led Tujue forces to defeat the Khitans. Wei Yunqi declared his intent to trade with Goguryeo and marched into its territory. Upon reaching a location 50 li (about 25 kilometers) from the Khitan camp, Wei Yunqi unexpectedly launched an attack and defeated the Khitan army. In 606, when the Eastern Tujue Qimin Khan visited the Sui court, Emperor Yang convened a grand gathering of musicians and artists from across the empire to entertain him. The following year, Emperor Yang visited Yulin, where he instructed Yuwen Kai to construct a temporary grand hall named the “Observation of Wind and Movement Hall.” This impressed the local foreign tribes, who believed it to be a divine achievement, showing their reverence by kneeling and bowing from ten li (about 5 kilometers) away and refraining from riding horses.

However, during the rebellion at the end of the Sui Dynasty, various regional leaders such as Xue Ju, Wang Shichong, Liu Wuzhou, Li Gu, and Gao Kaidao sought aid from the Eastern Tujue, leading to their rebellion against the Sui Dynasty. The Tujue supported these rebellions to weaken the Sui Dynasty.

In the southern regions, the southern central area was nominally under the control of the Sui court, with military garrisons stationed in Nanning Prefecture. However, the local powerful clan, the Cuan clan, held de facto control and eventually rebelled against the Sui Dynasty. In 597, Emperor Wen of Sui dispatched General Shi Wansui to suppress the rebellion, resulting in victory around the Xiru River and Dianchi area. Key figures of the Cuan clan, Cuan Zhen and Cuan Wan, were killed by Emperor Wen. By the end of the Sui Dynasty, the Cuan clan had split into two factions: the Eastern Cuan, known as “Wuman,” and the Western Cuan, known as “Baiman.” The Western Cuan consisted of six tribes, collectively referred to as the Liuzhao, with the Mengshe tribe evolving into the precursors of Nanzhao and Dali. Scholar Fang Guoyu observed that Sui’s strategy in the southern central region relied more on military force and less on political establishment.

In the southern coastal areas, there were regions like Linyi, Chitu, Zhenla (Chenla), and Poli. Emperor Yang of Sui dispatched envoys like Chang Jun and Wang Junzheng to establish relations with the Chitu country (likely located in the Kra Isthmus of the Malay Peninsula). In 608, Chang Jun and others brought 5,000 rolls of silk to present to King Qutan Lifu of Chitu. The envoy journeyed from Nanhai Commandery (modern-day Guangzhou, Guangdong Province) to Chitu. King Qutan Lifu also sent his son, Naxiejia, along with Chang Jun, to visit China, and Emperor Yang conferred titles and gifts upon Naxiejia.

In Northeast Asia, there were the Goguryeo, Silla (Silla), Baekje, Woguo (Japan), and Liuqiu. Goguryeo was a powerful state in Northeast Asia, with its capital at Chang’an (modern-day Pyongyang). Following the overthrow of the Southern Chen Dynasty, Goguryeo’s King Pyeongwon prepared defenses against the Sui Dynasty. In 598, King Jinpyeong of Silla led an army of over ten thousand to attack Liaoxi. Taking advantage of this, Emperor Wen of Sui launched a campaign with a force of three hundred thousand, employing both naval and land routes against Goguryeo. However, the rugged terrain led to heavy casualties and Emperor Wen had to retreat. King Jinpyeong of Silla sent envoys to sue for peace, resulting in a peaceful resolution.

Later, Emperor Yang of Sui continued Emperor Wen’s failed campaigns, launching three large-scale invasions against Goguryeo in 612, 613, and 614 due to Goguryeo’s alliance with the Tujue. These campaigns led to the squandering of resources, manpower, and a heavy burden on the people, contributing to the later rebellion against the Sui Dynasty.

Baekje sent envoys to the Sui court during Emperor Wen’s reign, and Emperor Yang of Sui continued this practice during the Daye era. Baekje also offered military support during Emperor Yang’s campaign against Goguryeo, ostensibly assisting the Sui forces while maintaining a friendly relationship with Goguryeo for its own benefit.

Silla sent envoys to the Sui court in 594, and Emperor Wen conferred titles upon its king, Jinpyeong. Emperor Yang of Sui also dispatched envoys to Silla during the Daye era. Woguo (Japan), during the period of the Asuka Dynasty, frequently sent envoys to China for diplomatic and cultural exchanges. In 607, Empress Suiko of Japan sent the envoy Ono no Imoko to present a letter to Emperor Yang of Sui. However, the letter’s language, specifically the phrase “Sunset has come to the Son of Heaven,” provoked Emperor Yang’s anger. The following year, Ono no Imoko returned with a new letter addressing Emperor Yang with more humility. In 608, Emperor Yang dispatched Pei Shiqing as an envoy to visit Japan. In 607 and 608, Emperor Yang also sent Zhu Kuan on two missions to Liuchiu (possibly referring to the Ryukyu Islands or Taiwan) to seek reconciliation and appease the country, but Liuchiu did not comply. In 610, Chen Leng and Zhang Zhenzhou led an army of ten thousand to attack Liuchiu, killing its leader Huan Sikezou, capturing thousands of men and women, and then departing. During the Sui Dynasty’s military campaigns, the people of Liuchiu engaged in trade activities with the Sui forces.

In summary, the Sui Dynasty’s foreign relations were characterized by the tributary system, where various nations recognized the supremacy of the Sui court. This led to diplomatic exchanges, tributary payments, and military support when necessary. However, the Sui Dynasty’s excessive spending and wastefulness, especially during Emperor Yang’s reign, contributed to its eventual downfall.

The Situation of “Ten Thousand Nations Coming to Court” during the Sui Dynasty

During the Sui Dynasty, a situation emerged where many nations came to the Sui court. Upon ascending to the throne, Emperor Yang Guang pursued a foreign policy of “bestowing lavish gifts upon those who come to the court; those who do not obey shall be attacked with military force.” Under his combination of benevolence and firmness, various foreign tribes submitted, and envoys from all directions came to the court.

In the second year of the Dàyè era (606 AD), Qimin Khan of the Göktürks came to the eastern capital Luoyang to pay his respects. “Every year in the first month, ten thousand nations come to court, staying until the fifteenth day, extending over eight li from the Duan Gate to the Jian Guo Gate.” Among the 44 chieftains of the Western Regions, “more than thirty nations” came to court. Powers from the north like the Göktürks and Khitans, from the east such as Goguryeo, Baekje, Silla, and Wa (Japan), and from the south like Linyi (modern-day Vietnam) and Chenla (modern-day Cambodia) all sent envoys to Luoyang for diplomatic relations. Luoyang became a hub of foreign emissaries and merchants, with bustling markets, making it a global center. The “barbarian tribes marveled and exclaimed that China was like a realm of immortals.” Emperor Yang Guang took great pride in this. However, beneath this grandeur, there was extravagant spending and an increasing burden on the common people.

Goguryeo

Goguryeo, located in Northeast Asia, resisted the Sui army’s invasion when Emperor Yang Guang sought to conquer it. In the 17th year of the Kāihuáng era (598 AD), King Yeongyang of Goguryeo led a force of over ten thousand soldiers to attack Liaoxi. Emperor Wen of Sui responded by mobilizing an army of three hundred thousand troops by land and sea to attack Goguryeo. However, due to the treacherous terrain and heavy casualties, Emperor Wen had to retreat. Subsequently, King Yeongyang sent envoys for peace, leading to a peaceful resolution.

Later, Emperor Yang Guang followed in Emperor Wen’s footsteps. In the third year of the Dàyè era (607 AD), due to an alliance between Goguryeo and the Göktürks, Emperor Yang Guang launched three large-scale wars against Goguryeo in the eighth, ninth, and tenth years of the Dàyè era (612-614 AD). The first campaign resulted in a disastrous defeat, wasting immense resources and exacerbating the burden on the people, ultimately contributing to the later uprisings at the end of the Sui Dynasty.

Baekje and Silla

Baekje sent envoys to the Sui court during Emperor Wen’s reign, and it was recognized as a vassal state with the title “Duke of Baekje, Governor of Fang Commandery.” When the Sui Dynasty conquered the Southern Chen Dynasty, some warships drifted into Baekje’s territory. Baekje provided assistance and sent supplies back, congratulating the Sui Dynasty on its unification. During Emperor Yang Guang’s campaigns against Goguryeo, Baekje had seemingly pledged support to the Sui forces while maintaining friendly relations with Goguryeo.

Silla sent envoys to the Sui court during the 14th year of the Kāihuáng era (594 AD), and its king was recognized as the “Duke of Lelang, King of Silla.”

Emperor Yang Guang’s Campaigns against Goguryeo

Emperor Yang Guang launched a third campaign against Goguryeo, ignoring internal and external crises. He mustered forces from across the empire. However, due to internal turmoil, many troops did not arrive as planned. General Lái Hù’ér achieved a major victory at Bìshē City (modern-day Dalian, Liaoning Province), pushing forward to Pyongyang. Facing overwhelming pressure, Goguryeo surrendered, and its minister, Húsī Zhèng, who had defected to Goguryeo, was returned. Emperor Yang Guang accepted Goguryeo’s surrender and, given the domestic unrest, decided to return to the capital.

Korea and Japan

During the early Sui Dynasty, the Korean Peninsula’s three kingdoms – Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla – were vassal states that sent envoys and tribute to the Sui court. Japan also engaged in occasional diplomatic exchanges, aiming to maintain a relatively equal status rather than being considered a vassal.

Western Regions and Other Countries

The Sui Dynasty also engaged in commercial interactions with many European countries, stimulating trade along the Silk Road. Goods from China were exported to Europe, and merchants from regions such as Rome and Persia lived in Dàxīng City. European envoys also visited Dàxīng City for diplomatic purposes.

Military System of the Sui Dynasty

Organization of Forces:

In terms of military organization, the Sui Dynasty established a system of regional guards, drawing from the precedent of the Twelve Great Generals system during the Western Wei and Northern Zhou dynasties. Offices like the Ministry of Guard and the Ministry of Martial Affairs were responsible for overseeing the imperial guards stationed within the capital. The Military Marquis’ Office managed the capital’s defense and patrolling, with officials of high ranks appointed.

The Sui Dynasty initially continued the practice from the Northern Zhou by setting up the Twelve Guards, which later evolved into the Sixteen Guards. The Twelve Guards were subdivided into Left and Right Yì Guards, Left and Right Fierce Cavalry Guards, Left and Right Martial Guards, Left and Right Garrison Guards, and Left and Right Imperial Guards. These guards were responsible for defense and wartime campaigns. During times of conflict, the emperor appointed commanders-in-chief or generals to lead military campaigns and establish command structures. For instance, during the Chen-Dynasty campaign, which was a large-scale operation, Yang Guang, Yang Jun, and Yang Su were appointed to coordinate the efforts.

In the third year of the Dàyè era (607 AD), Yang Guang expanded the Twelve Guards into a system known as the Guards’ Administrative Bureau (Wèi Tǒng Fǔ). This expansion aimed to increase military strength, enhance the central guard, and decentralize power from various military commanders. The newly established Four Bureaus were Left and Right Backup Body Bureaus and Left and Right Guardhouse Oversight Bureaus. The Twelve Guards were responsible for commanding palace guards and capital defense, while the Four Bureaus managed other aspects of imperial security and administration.

Military Regions:

Emperor Wen of Sui divided the country into several military regions, each under the command of a General-in-Chief responsible for regional defense during peacetime and leading campaigns during wartime. These Generals-in-Chief oversaw their respective General-in-Chief Offices, categorized as upper, middle, and lower tiers. Additionally, there were four Grand Generals, with Yang Guang stationed in Bingzhou, Yang Jun in Yangzhou, Yang Xiu in Yizhou, and Wei Shikang in Jingzhou. The Sui Dynasty had around thirty to fifty General-in-Chief offices, grouped into four major military regions: East, West, South, and North, with Chang’an as the central hub. These regions defended against external threats and guarded strategic locations. Notably, the northern borderlands were a primary focus, defending against the Turks.

The military regions included:

- Eight northern and northwestern regions, primarily defending against the Turkic Khaganate.

- Seven northeastern regions, guarding against the Turkic Khaganate and the Khitans.

- Eight central and western regions, safeguarding the capital and controlling key river sources.

- Nine southeastern regions, protecting strategic locations in the south.

- In addition, there were Dezhou to defend against the Tuyuhun and Suizhou and Lùzhou to counter southwestern tribes.

art and architecture of the Sui dynasty

During the Sui Dynasty, due to the close relationship between politics and religion, painting received significant attention. While the focus of Sui Dynasty painting remained on figures and stories of deities and immortals, landscape painting had developed into an independent genre. Zhān Zǐqián and Dǒng Bórén were renowned painters of the time, often mentioned alongside the likes of Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin Dynasty and Lù Tànwēi and Zhāng Sēngyóu of the Southern Dynasties, collectively known as the “Four Great Painters of the Early Tang Dynasty.” Zhān Zǐqián served during the Northern Qi, Northern Zhou, and Sui Dynasties, holding positions such as Advisor to the Court and later Commander of the Imperial Guard. Although his Buddhist painting “Lotus Sutra Transformation” and genre painting “Figures in a Chariot in Chang’an” have not survived, his landscape painting “Spring Excursion” displayed a distinctive brushwork technique, featuring vibrant green hues. It demonstrated rational spatial perspective arrangements, emphasizing the relationship between foreground and background, and the proportion of mountains, trees, and figures. This work, with its meticulous attention to spatial relations, is considered a masterpiece that resolved the spatial challenges of representing people larger than mountains and water. It marked the initiation of the scroll landscape painting genre and is regarded as the official precursor of Chinese landscape painting according to the Yuan dynasty work “Huajiàn.”

The painter Wèichí Bázhí Nà, hailing from the Western Regions (present-day Xinjiang), excelled at depicting figures from the western regions and was referred to as “Dà Wèichí” (Great Weichi). He was skilled at shading and blending shadows, using a technique known as “concave-convex method.”

Calligraphy during the Sui Dynasty was characterized by its meticulous and forceful style, adhering closely to established rules. The foundations of the distinguished styles of the early Tang Dynasty had already begun to take shape during this period. Noteworthy calligraphers included Dīng Dàohù, Shǐ Líng, and Zhì Yǒng. Ink writings such as the “Thousand-Character Classic” and sutra transcriptions were also prominent. Monumental inscriptions were a significant facet of Sui Dynasty calligraphy, with inscriptions like the “Longzang Temple Stele,” “Qǐfǎ Temple Stele,” and “Biography of Dòng Méirén” showcasing distinctive calligraphic styles. During the late Sui and early Tang periods, the calligrapher Yú Shìnán stood out. Alongside Ouyang Xun, Chǔ Suìliáng, and Xuē Jì, he was hailed as one of the “Four Great Calligraphers of the Early Tang Dynasty.”

Music

Sui Dynasty music was influenced by the musical traditions of northern ethnic groups and the old music of the Southern Dynasties Song and Qi, incorporating elements of “barbarian music.” During the reign of Emperor Yang of Sui, the imperial court established nine music divisions, including Qing Yue, Western Liang, Gao Li, Tianzhu (India), Kang Guo, Shu Le, An Guo, Goguryeo, and Li Bi. Musical instruments of the era included the quxiang pipa, shutou konghou (a type of harp), dalagu drum, and ge drum, which were all inherited from northern ethnic groups and regions in the Western Regions. By this time, the understanding of musical scales had already expanded to seven notes rather than just five.

Wàn Bǎocháng and Hé Tuǒ were renowned musicians of the Sui Dynasty. Hé Tuǒ, originally from the country of Ho (modern-day Uzbekistan), was also well-versed in philosophy. In 592 AD, he was appointed as the Doctor of the Imperial Academy to formulate the court music. Although discussions among eminent officials, including Wàn Bǎocháng, took place, no consensus was reached at that time. Hé Tuǒ ultimately used a strategy to have Emperor Wen of Sui adopt the Huangzhong mode, resolving the dispute. Hé Tuǒ also created the “Hé Tuǒ Chariot” for Emperor Yang of Sui. He authored works such as “Essentials of Music” and “Explanatory Notes on the Book of Changes.” Wàn Bǎocháng composed the “Music Scores.” During Emperor Wen of Sui’s reign, he faced challenges from “barbarian music” and the musical remnants of the Southern Dynasties. In order to establish standardized court music, Emperor Wen convened Niú Hóng, Xīn Yànzhī, and Hé Tuǒ, among others, to reform the music, resulting in a unified national music system. Despite prolonged discussions among influential ministers like Zhèng Yì, Sū Wēi, and Hé Tuǒ, no consensus was reached. Although Wàn Bǎocháng offered suggestions, his low status led to his suggestions being overlooked. Nevertheless, he secured Emperor Wen of Sui’s approval to use his proposed “Water and Ruler Modes” for tuning instruments. Despite his aspirations, Wàn Bǎocháng faced envy from certain influential figures, and he passed away without fulfilling his ambitions. His music was described as “Western Regions music, the music of the four barbarians, not suitable for the cultured.” The “Book of Sui – Music” incorrectly attributes the theory of the “Eighty-Four Modes” to Zhèng Yì, when in reality, it was the research achievement of Wàn Bǎocháng.

Architecture of the Sui Dynasty

During the Sui Dynasty, the architecture inherited elements from the Six Dynasties period and laid the groundwork for the architectural maturity of the Tang and Song Dynasties in traditional Chinese architecture. Despite its relatively short duration, the Sui Dynasty made significant advancements in architectural technology due to Emperor Yang’s ambitious construction projects, including palaces and pleasure gardens. The exchange of architectural techniques between the previously divided Northern and Southern Dynasties during this period paved the way for the refined architectural system of the Tang Dynasty.

Physical relics from the Sui Dynasty are scarce, with only a few examples of brick and stone structures surviving, while wooden structures have not. Notable examples include the Zhaoxian Anji Bridge and several brick and stone pagodas. The architectural forms of the Sui Dynasty can be glimpsed through indirect sources such as Dunhuang murals and pottery fragments. The Sui Dynasty often utilized the “man” style intercolumniation, with bracket sets extending outwards to create the double-eaves single-corridor and triple-eaves single-jump styles.

Architectural Characteristics

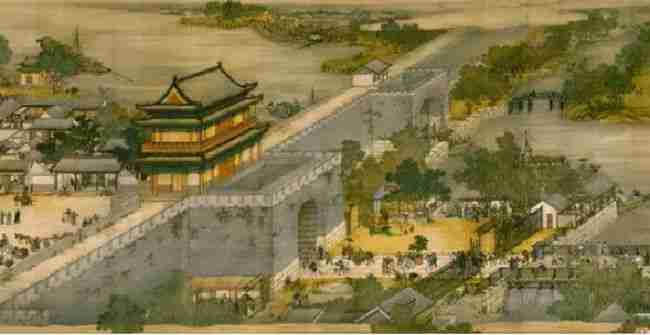

The Sui Dynasty marked a period of architectural maturity in ancient China. Notable achievements include the well-planned construction of Daxing City, the excavation of the Grand Canal, and the creation of the earliest known open-spandrel segmental arch stone bridge, the Anji Bridge.

Urban planning and architectural style were characterized by grandeur and magnificence. The capital city, Chang’an, built upon the foundations of Daxing City, became the largest city in the world at the time.

In terms of materials, there was an increasing use of bricks, with a rise in the number of brick tombs and pagodas. The firing of colored glazes (liuli) also improved during the Sui Dynasty, with wider applications.

Advancements were made in architectural technology, with more refined use of wooden structural frames that took into account material properties. Standardized design based on “materials” for wooden structural frames emerged, leading to the gradual standardization of proportions and forms of architectural components. Specialist craftsmen (duliao jiang) skilled in laying out plans and executing construction also appeared.

Architectural and sculptural decorations became further integrated and refined, resulting in a unified and harmonious style. Residential buildings adhered to strict regulations for the size, number of rooms, bracket sets, decorations, and colors of their gate halls, reflecting China’s rigid feudal hierarchical system. The extant remains from this period, including palaces, tombs, grottoes, pagodas, bridges, and urban palaces, demonstrate high artistic and technological levels in terms of layout and design. Sculptures and murals, in particular, are exceptionally exquisite, representing the pinnacle of architecture in the early feudal period of China. The architectural characteristics include gently sloped roofs with deep overhanging eaves, proportionally large bracket sets, sturdy columns, frequent use of paneled doors and rectangular windows, and a dignified and straightforward style.

Architectural Examples

A representative architectural structure of the Sui Dynasty is the Anji Bridge, which is rare in terms of historical documentation of bridge construction between the Sui and Tang Dynasties. The Anji Bridge, designed and built by craftsman Li Chun in Zhao County, Hebei Province, stands over the Mianchi River to the south of the city. With only one segmental arch, the bridge spans an impressive 38 meters. Small open-spandrel segments are added at the ends of the bridge, creating an empty spandrel design. This construction method was first seen in a bridge in Ceret in the south of France during the 14th century and was later applied in modern engineering starting from 1912. Li Chun’s bridge, however, predated this European example by eight centuries, making it an engineering marvel unique in China and among the world’s oldest surviving bridges.

Another notable creation is the “Liuhe City” designed by He Chou, featuring an automatic alarm system and rotating crossbows capable of targeting and firing automatically.

Innovation and Technology

In the field of robotics, Yang Guang had a wooden puppet automaton created based on the likeness of his close friend Liu Bian. The puppet was equipped with mechanisms to sit, stand, and even bow.

A highlight in architectural innovation was the design and construction of the Guanfengxing Hall by Yu Wenkai. This mobile palace featured wheels that allowed it to be moved from one location to another.

Astronomy

Liu Zhuo’s development of the “Imperial Calendar” marked a cutting-edge astronomical achievement of the time.

The Sui Dynasty is credited with inventing the world’s earliest form of woodblock printing, producing various colored papers.

Mathematics

The invention of the equidistant quadratic interpolation formula further evolved into the unequal equidistant quadratic interpolation method.

The Sui Dynasty’s historical records documented the earliest instances of sweet urine in diabetic patients, predating Thomas Willis’ recognition of glycosuria by over a thousand years. The compilation of the “Treatise on the Origins of Various Diseases” summarized medical practices since the Wei and Jin Dynasties, providing a detailed and accurate description of the concepts of etiology and syndrome differentiation in traditional Chinese medicine. This work became the first specialized treatise on the subject.

Sui dynasty Administrative System

The administrative divisions of the Sui Dynasty underwent significant changes, reflecting transitions from earlier periods and shaping the subsequent development of China’s administrative system. Despite its short duration, the Sui Dynasty played a crucial role in the evolution of administrative organization.

The Sui Dynasty restored a two-tier system of provinces (州) and counties (县), reminiscent of the structure used during the Qin Dynasty. At a macro level, the Sui Dynasty served as a transitional phase in the historical evolution of China’s administrative divisions, even though it was relatively less mature.

During its brief history, the Sui Dynasty experienced two major changes in its administrative divisions. Emperor Wen of Sui, Yang Jian, unified much of the realm and reformed the administrative structure. In the face of the chaotic state of the provincial and county divisions that had persisted since the late Eastern Han Dynasty, he abolished the system of commanderies (郡) and introduced a two-tier system of provinces and counties. Following the successful reunification of the Southern and Northern Dynasties under Emperor Yang of Sui, Yang Guang, the administrative system underwent another transformation. The provinces were reverted to commanderies, returning to a structure resembling that of the Qin Dynasty.

By the late Eastern Han Dynasty, there were thirteen provinces, governing over a hundred commanderies. After the Three Kingdoms period, the number of provinces increased to nineteen during the reunification under the Western Jin Dynasty. However, over the next two centuries, the division of the realm into states and regions led to a proliferation of provinces and commanderies, resulting in a complex administrative structure with 211 provinces, 508 commanderies, and 1,124 counties by the time of the Sui Dynasty’s emergence.

In the face of this complexity, Emperor Wen of Sui initiated reforms. In 583, he abolished the commanderies and introduced a two-tier system of provinces and counties. Following the defeat of the Chen Dynasty in 589, which marked the end of the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Emperor Wen further implemented this system throughout the unified realm.

Emperor Yang of Sui, Yang Guang, made another change in 607 by reverting provinces to commanderies. He introduced the system of commanderies and counties, restoring the structure akin to the Qin Dynasty. Additionally, he established monitoring prefectures (监察州) within commanderies, imitating the system of Emperor Wu of Han, to oversee the functions of local officials.

While the Sui Dynasty officially adopted a two-tier system that resembled the structure of the Qin and Western Han Dynasties, the actual number of commanderies far exceeded that of the earlier periods, totaling 190. This vast number posed challenges to efficient governance. In response, Emperor Yang established monitoring prefectures to supervise commanderies, contributing to a more centralized system.

The Sui Dynasty’s administrative divisions played a significant role as an intermediary phase between the province-oriented structure and the subsequent Dao (道) and Lu (路) system of the Tang and Northern Song Dynasties, which reintroduced a three-tier hierarchy.

In terms of territorial expansion, the Sui Dynasty saw remarkable growth. It extended its dominion to distant regions such as the Ili Valley, where Yiwu (伊吾) Commandery was established, and the southeastern regions of modern Qinghai and Xinjiang were organized into four new commanderies.

In terms of administrative ranks, the Sui Dynasty adopted a nine-grade system (九品官人法) similar to that of the Tang Dynasty. This system applied to officials at all levels, from central government officials to local administrators. However, due to limited available records, specific details about the implementation of this system are sparse.

The Sui Dynasty’s administrative organization underwent shifts in both centralization and decentralization, responding to the challenges of governance and reflecting the dynasty’s efforts to balance power and control. Despite its relatively short duration, the Sui Dynasty’s administrative reforms laid the foundation for subsequent developments in China’s administrative system.

The social structure of the Sui Dynasty was characterized by the coexistence of a grassroots society comprised of farmers and local magnates, and a court society centered around the emperor. These two distinct societal segments operated under separate rules and statuses, each with its own distinct political and economic systems. Interaction between these two societies was relatively limited.

The Sui Dynasty’s social fabric was woven from these two intertwined yet distinct components, each with its own unique dynamics and roles within the broader framework of governance and society.

What religion was the Sui Dynasty?

During the Sui Dynasty, the dominant religious belief was Buddhism. Since the period of the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism were collectively known as the “Three Teachings” and held sway over the realm of thought.

Emperor Wen of Sui advocated for a harmonious coexistence of religions and Confucianism, adopting a strategy of emphasizing the equal importance of the Three Teachings. He allowed Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism to complement each other in governing the state.

Due to the openness of the state, Zoroastrianism, prevalent in West Asia, also spread widely in China during this period. The Sui Dynasty witnessed a peak in the popularity of Buddhism, which was closely tied to the emperor. When Emperor Wen ascended the throne, he believed in a prophecy that he would become emperor and revive Buddhism. He considered himself blessed by the Buddha and attributed his success to Buddhism. Emperor Wen actively promoted Buddhism and, in his later years, even marginalized Confucianism, making Buddhism the state religion of the Sui Dynasty.

Sui Dynasty Taoism

The Sui Dynasty implemented a policy of compatibility between Buddhism and Taoism, with a primary emphasis on revering Buddhism, but also showing significant regard for Taoism.

Emperor Wen of Sui named his inaugural era “Kaihuang,” drawing inspiration from Taoist scriptures. He sponsored the construction of Taoist temples and supported Taoist priests to promote the development of Taoism. Emperor Yang of Sui displayed even greater reverence for Taoism, constructing ten Taoist temples in Chang’an during his reign.

The Sui Dynasty, though short-lived, witnessed a notable development within Taoism known as the rise of “Neidan” or Internal Alchemy. Daoist hermit Su Xunlang, residing in Mount Mao of Jiangsu, authored the “Zhidao Pian,” elucidating the practice of internal alchemy. This marked the inception of Neidan within Taoism. Su Xunlang also compiled the “Longhu Jinye Huandan Tong Yuan Lun,” which incorporated the elixir of spiritual transformation into inner alchemy, thereby advocating dual cultivation of essence and life as the core of internal alchemical practice.

Origin and Development of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty

Prevalence of Taoism before the Sui Dynasty

Taoism, as one of China’s traditional religions, has its roots traceable to the Han Dynasty.

Prior to the Sui Dynasty, Taoism underwent a prolonged evolution, shaping its distinctive theoretical framework and practical methods.

By the time of the Sui Dynasty, Taoism had already established a foothold in society, gradually penetrating the upper echelons.

Characteristics and Trends of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty

During the Sui Dynasty, Taoism experienced further development and prosperity.

Emperor Wen of Sui, Yang Jian, held Taoism in high regard, constructing numerous Taoist temples and dispatching envoys to acquire authentic Taoist teachings from the southern regions.

In the era of Emperor Taizong, Li Shimin, Taoist culture flourished even more. The religious system of Taoism was refined, its doctrines and Taoist classics underwent deeper study.

Prominent Schools and Figures of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty

Significant schools of Taoist culture in the Sui Dynasty included the Quanzhen School and the Taiyi School. Among them, the Quanzhen School was one of the most important Taoist schools during this period. Its founder, Wang Chongyang, was a knowledgeable monk who established the Quanzhen School, which already held a degree of influence during the Sui Dynasty.

The Taiyi School, founded by Zhang Daoling, propagated the method of internal alchemy to its disciples, establishing a solid foundation for Taoist philosophy.

Influence of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty on Society

Position of Taoism in the Sui Dynasty Society

Throughout the Sui Dynasty, as Taoist culture continued to develop, its position within society steadily ascended.

Taoism, standing alongside Buddhism and Confucianism as one of the Three Teachings, gained even more prominence during the Sui Dynasty, surpassing even Buddhism and Confucianism in terms of influence.

Being one of Emperor Yang’s beliefs, Taoism spread widely within the imperial court, becoming a combination of religious belief and political tool.

Impact of Taoist Doctrines and Practices on Social Life

The profound impact of Taoist cultural doctrines and practices on social life cannot be understated. Taoism emphasized “wu wei” or “non-action,” advocating alignment with the Tao, human nature, and natural principles. It stressed inner cultivation and the pursuit of self-transcendence.

These teachings and practices had positive effects on individual thoughts and behaviors, maintaining social order, advancing political culture, and guiding moral ethics.

Influence of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty on Literature and Art

Taoist culture exerted a significant influence on the literary and artistic domains of the Sui Dynasty.

In Sui Dynasty literature, many poets skillfully integrated Taoist and other religious or philosophical ideas into their works. Examples include Wang Zhihuan’s “Climbing Stork Tower” and Du Fu’s “Climbing High.”

In the realm of art, the influence of Buddhism and Taoism intertwined in Sui Dynasty artworks. The incorporation of foreign religions like Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism gradually blended with Taoism, resulting in a diverse artistic landscape.

Impact of Taoist Thought in the Sui Dynasty on Later Philosophical Ideas

During the Sui Dynasty, Taoist thought played a significant role in the broader dissemination and reception of philosophical ideas within Chinese society, thus leaving a profound imprint.

Taoism advocated the unity of heaven and humanity, asserting that the Tao governed the highest natural law, influencing the cosmos, life, and human conduct. This ideology deeply permeated traditional Chinese religious and cultural frameworks.

With Taoism’s expansion during the Sui Dynasty, this system of thought underwent influence and transformation from other philosophical systems.

For instance, Wang Can and Xiao Tong’s school of thought absorbed Taoist ideals into Buddhist and Confucian influences, resulting in the concept of “transforming states into heaven.”

Contributions and Impact of Taoist Culture in the Sui Dynasty

Taoist Culture’s Impact on Chinese Culture

Despite its short duration, the Sui Dynasty played a crucial role in the evolution of Chinese culture. Taoist culture became an integral part of this period, leaving a profound impact and contributing to the broader tapestry of Chinese culture.

The emphasis of Taoist thought on personal cultivation left an indelible mark on the development of Sui Dynasty scholars and their intellectual consciousness.

As an essential element of Daoist philosophy, Taoist thought played a significant role in shaping the foundations of later Taoist culture, influencing both Buddhist and Confucian developments.

Taoist Culture’s Impact on Global Culture

In a world characterized by development and globalization, the influence of Chinese culture is increasingly expanding across the globe.

Taoist culture, as a vital component of traditional Chinese culture, also contributes significantly on a global scale.

Taoism boasts adherents and scholars worldwide, with its philosophical concepts and values being recognized and adopted globally, encouraging the pursuit of inner tranquility and peace.

The Role of Taoist Culture in the Inheritance and Development of Modern Taoism

The Sui Dynasty witnessed a lengthy process of Taoist culture’s development, yielding numerous achievements.

In the context of the inheritance and development of later Taoist culture, the cultural legacy of the Sui Dynasty plays a pivotal role, guiding and propelling various aspects of Taoist thought, doctrines, art, culture, and customs.

The impact of Sui Dynasty Taoist culture on modern Taoist culture holds profound significance.

The contributions and influence of Sui Dynasty Taoist culture on Chinese culture, global culture, and subsequent developments in Taoism cannot be underestimated. Through its unique ideas, aesthetic styles, and humanistic concerns, Taoist culture has left a lasting mark and contributed significantly to the evolution of both Chinese and global cultural history.

Sui Dynasty Buddhism

The Buddhist faith during the Sui Dynasty spanned thirty-seven years, from the first year of Emperor Wen’s Kaihuang era (581) to the second year of Emperor Gong’s Yining era (618). The Sui and Tang Dynasties marked the zenith of Buddhism in China, with the Sui Dynasty’s brief existence being instrumental. Though a newly founded dynasty, the Sui unified the political landscape of the North and South, resulting in a synthesis of diverse cultures. Buddhism underwent a similar synthesis, embracing both Southern and Northern systems, fostering new teachings and sects, and forging distinctive characteristics during this unified period.

Buddhism Prevailed during the Sui Dynasty

Since the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism collectively represented the Three Teachings, dominating the intellectual sphere. Emperor Wen of Sui advocated reconciling religion and Confucianism, adopting a strategy of equal emphasis on the Three Teachings. Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism were all integrated to complement governance. Additionally, the Zoroastrianism that prevailed in the West was also disseminated in China.

Buddhism reached its pinnacle during the Sui Dynasty due to its close connection with the emperors. Emperor Wen revered Buddhism, attributing his success to it. In response to a prediction, Emperor Yang of Sui, Yang Guang, would revive Buddhism, and Emperor Wen ardently propagated Buddhism, even sidelining Confucianism. By 581, Emperor Wen invited secluded monks to participate in the nation’s affairs, and monks and nuns were allowed to ordain freely. Emperor Yang also actively supported Buddhism, personally receiving ordination from the Tiantai school’s master, thus becoming a Buddhist disciple. However, the emperors tightly controlled Buddhism, gathering influential southern Buddhist scholars for better regulation and ordering them to show reverence to the monarch.

Prominent Buddhist Sects and their Philosophies

During this time, the dominant Buddhist sects included the Tiantai School, the Sanlun School, and the Sanjie School. The Tiantai School emphasized integrating “teaching” and “meditation” to achieve a harmonious whole, asserting the oneness of all things within the dharma realm. The primary practice was the combination of meditation and contemplation. The Sanlun School was renowned for its study of texts like the “Madhyamaka-karika,” the “Dvadashamukha-sastra,” and the “Shata-sastra.” This school maintained that all phenomena, both worldly and transcendent, were born from various causes and conditions, a result of multiple factors and circumstances converging.

Buddhist Cultural Contributions during the Sui Dynasty

In total, over 5,000 temples and pagodas were constructed, tens of thousands of Buddhist statues were sculpted, and tens of thousands of Buddhist scriptures were translated during the Sui Dynasty. Buddhist texts became more prevalent than Confucian classics by hundreds of times. Emperor Wen’s fervent devotion led to the construction of 83 stupas in various provinces within just two instances, the most notable being the Daxingshan Monastery. He funded and sponsored the creation of Buddha statues for the capital and major cities, wrote 460 volumes of scriptures, and repaired 400 ancient sutras. Emperor Yang continued this legacy by restoring 612 collections, comprising over 29,000 volumes, establishing an institute for translating scriptures, and translating a total of 90 sutras spanning 515 volumes.

Buddhism flourished during the Sui Dynasty, a testament to the emperors’ profound support and the religion’s cultural impact on Chinese society. This era laid a strong foundation for the subsequent golden age of Buddhism in the Tang Dynasty.

Confucianism in the Sui Dynasty

After the challenges posed by the Xuanxue movement during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, traditional Confucianism seemed to be waning, compounded by the influx of Buddhism. These influences significantly impacted the intellectual and scholarly realms of the Sui Dynasty’s ruling elite. However, in reality, Confucianism continued to pervade throughout feudal society, even becoming the dominant ideology of ruling classes within feudal dynasties. Under the vigorous promotion of Emperor Wen of Sui, Confucianism experienced substantial growth during the Sui Dynasty.

Development of Confucianism in the Sui Dynasty

The Han Dynasty was the zenith of Confucianism, yet after the upheaval following the Wei and Jin periods, traditional Confucian thought faced considerable challenges due to the ongoing turmoil.

However, following the establishment of the Sui Dynasty, Confucianism experienced a revival and entered a new peak after the decline during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties.

Emperor Wen of Sui was a feudal monarch who firmly believed in Confucian thought. Upon his ascension to the throne, he lamented the decline of Confucianism during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties and recognized its renewed significance in the new context. Emperor Yang of Sui was even more resolute in promoting Confucianism, elevating the social status of Confucius and his descendants, such as conferring posthumous titles like “Duke of Zou” and later “Marquis Shao of Seng.” The latter even referred to Confucius as the “Teacher and Master.”

Moreover, Emperor Wen of Sui launched a nationwide campaign to collect and preserve Confucian classics, which continued throughout his reign and into his later years.

Apart from this, Confucianism was deeply respected by officials and scholars of the Sui Dynasty. Combined with the prevalence of Confucian classics, the enthusiastic support of the imperial family and officials sparked a resurgence of Confucian scholarship. Many Confucian scholars authored works during this period, and the Sui Dynasty produced a significant number of writings related to Confucianism. For instance, “Sui Shu,” an official history of the Sui Dynasty, contains more than 27 sections and over 380 volumes dedicated to Confucian studies. The influence of Confucianism during the Sui Dynasty was profound and marked a new peak since the Han Dynasty.

Status of Confucianism in the Sui Dynasty

During the early Sui Dynasty, most courtiers endorsed Confucianism as the mainstream ideology. Emperor Wen of Sui officially established Confucianism as the guiding ideology for governance, treating it as the foundation of statecraft. He issued edicts emphasizing the importance of Confucian teachings and rites in governance, believing that the fate of the state hinged on the practice of rituals.

Emperor Wen promulgated decrees, making Confucianism a cornerstone of his governance. Emperor Yang of Sui continued this tradition, recognizing that promoting Confucianism was crucial for social harmony and stability. Thus, Confucianism’s role extended to various aspects of governance, including rituals and personnel management.

In summary, Confucianism experienced a resurgence during the Sui Dynasty due to historical necessity, the patronage of the imperial family and officials, and its suitability for consolidating imperial authority. The Sui Dynasty’s embrace of Confucianism facilitated both historical reflection and the consolidation of centralized power, leading to a revival of Confucian thought that thrived in this unique historical context. This revival was later acknowledged and praised by scholars of the Tang Dynasty in “Sui Shu: Introduction to the Records of Confucian Scholars.”

Sui Dynasty famous characters

There were many notable figures in the Sui Dynasty, some of whom are introduced as follows:

Cheng Yaojin: Originally named Yaojin, he was from Dong’e in Jizhou. He was exceptionally brave and skilled in mounted combat. During the chaotic end of the Sui Dynasty, Cheng Yaojin gathered hundreds of followers to defend his hometown.

Emperor Yang of Sui (Yang Guang): Originally named Yang Ying, with the courtesy name Adu, he was from Huayin in Hongnong. He was the second emperor of the Sui Dynasty and the son of Emperor Wen of Sui and Empress Dugu. He is known for his dragon boat beauty pageant, during which he selected the “Palace Foot Maiden” Wu Jiangxian as his concubine.

Qin Qiong: A renowned general of the late Sui Dynasty and early Tang Dynasty. He gained fame for his military exploits. During the Sui Dynasty, he was taken under the wing of the junior commandant of the cavalry, Pei Renji, and was given the honorary title of “Qiong.”

Emperor Wen of Sui (Yang Jian): Yang Jian, from Huayin in Hongnong, was the founder of the Sui Dynasty. Before inheriting the title of Yang Zhong, he sought advice from his father, Yang Zhong, when the powerful official Yuwen Hu tried to gain his favor. Yang Zhong responded, “It is difficult for two sisters-in-law to coexist, so you should not go.”

Other notable figures and their achievements during the Sui Dynasty include Zhai Rang, Li Mi, Empress Dugu (Dugu Jialuo), He Ruobi, Han Qinhu, Niu Hong, Shi Wansui, Yuwen Kai, He Tuo, He Chong, and more.

what did the Sui dynasty accomplish?

The Sui Dynasty’s major achievements are as follows:

Establishment of Political Systems: The Sui Dynasty established significant political institutions, including the Three Departments and Six Ministries system, and implemented legal reforms.